All Saints' Church, Wigan

All Saints' Church in Wallgate, Wigan, Greater Manchester, England, is an Anglican parish church. It is in the deanery of Wigan, the archdeaconry of Warrington and the Diocese of Liverpool.[1] The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building,[2] and stands on a hill in the centre of the town.[3]

| All Saints' Church, Wigan | |

|---|---|

| Wigan Parish Church | |

All Saints' Church, Wigan, from the west | |

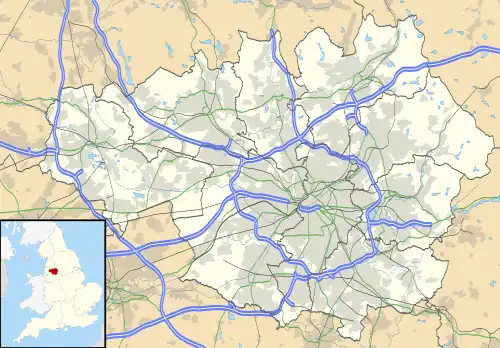

All Saints' Church, Wigan Location in Greater Manchester | |

| 53.5460°N 2.6328°W | |

| OS grid reference | SD 582,057 |

| Location | Wallgate, Wigan, Greater Manchester |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Wigan Parish Church |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 24 October 1951 |

| Architect(s) | Sharpe and Paley (rebuilding) E. G. Paley (addition to tower) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Perpendicular, Gothic Revival |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Sandstone, |

| Administration | |

| Province | York |

| Diocese | Liverpool |

| Archdeaconry | Wigan |

| Deanery | Wigan |

| Parish | Wigan |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Revd Bill Matthews |

| Curate(s) | Revd R. Sheehan |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Karl Greenall |

| Churchwarden(s) | Mr Graham Hart Mr Frank Wells |

| Parish administrator | Mr Mervyn Reeves |

History

The oldest fabric in the church is to be found in the lower parts of the tower which date from the later part of the 13th century. The belfry stage was probably added in the 16th century.[4] Between 1845 and 1850 the church was rebuilt, other than the tower, the north chapel, and two turrets between the chancel and the nave. The architects responsible were Sharpe and Paley of Lancaster. The total cost of this was £15,065 (equivalent to £1,710,000 as of 2021).[5][6] In 1861 E. G. Paley, now working alone, added another stage to the tower including clock faces and pinnacles.[4] The church was restored and its exterior partly re-faced in 1922.[2] Further restorations and repairs have been carried out since then.[3]

Architecture

Exterior

The church is constructed in sandstone.[2] Its architectural style is Perpendicular, following the style of the church it replaced.[4][lower-alpha 1] The plan consists of a six-bay nave, a two-bay chancel, both of which have a clerestory, a south aisle with a porch at its west end, a north aisle with a two-bay chapel at the west end and a tower at its junction with the chancel, and a vestry to the north of the chancel. Between the nave and the chancel are the octagonal turrets remaining from the medieval church; these have crocketed caps. Along the sides of the church are embattled parapets and crocketed pinnacles. At the west end of the church is a six-light window, and the east window has seven lights.[2]

Interior

Inside the church are six-bay arcades carried on quatrefoil piers. The roof is coffered. There are corporation stalls of 1850.[2] The reredos and pulpit were designed by Paley. The font has an octagonal bowl with a quatrefoil frieze and incorporates a fragment from the 14th or 15th century. The chancel screen of 1901 was designed by W. D. Caroe. Built into the splay of a north window is a Roman altar. The stained glass includes fragments in the north window dating from the 15th century, that were reassembled in 1956–57 under the direction of Eric Milner-White. Elsewhere are 19th-century windows by William Wailes, Heaton, Butler and Bayne, Hardman & Co., Lavers and Barraud, Clayton and Bell, and Burlison and Grylls. The monuments include a couple in the south chapel that are badly defaced. These are considered to be effigies of Sir William de Bradshaigh, who founded a chantry in the church in 1338, and his wife, Mabel. The female effigy was re-cut, and the male effigy was copied, by John Gibson in about 1850. There are also memorials to James Bankes, who died in 1689, and John Baldwin, who died in 1726. On the east wall of the chapel are marble monuments to the 23rd Earl of Crawford, who died in 1825, and his wife, and to the wife of the 24th Earl of Crawford who died in 1850.[4] There is a ring of ten bells, all cast in 1935 by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough.[8]

Organ

The earliest record of an organ is in 1620 when there was an organ on the screen between the chancel and the nave. A new instrument, built in 1623, was destroyed by Parliamentarian soldiers in 1643. In 1714 another organ was built in the same place, with a passage of twelve feet beneath it obstructing the view of the chancel. It remained in place until 1844, after which another was installed at the west end of the Leigh Chapel. This instrument was started by Richard Jackson of Liverpool, and finished by William Hill and Son of London. It was re-built by Hill in 1867, and sited under the tower. In 1877 the organ was moved to the eastern end of the Leigh Chapel. The main case, designed by Paley, dates from this time. In 1886 it was moved again to the western bay of the Leigh Chapel.

In 1901, when Sir Edward Bairstow was organist, the instrument was rebuilt by Norman & Beard of Norwich. Parts of the former organ were retained, but most was new. Further work was done in 1906 and 1948. It remained in use until the latest re-building in 1963. The work was done by William Hill and Son and Norman and Beard, also known as Hill, Norman & Beard who had a connection of more than 100 years with the parish church. Most of the 1901 instrument was retained after restoration and re-voicing. The pneumatic action was replaced with electro-pneumatic action, and a new detached console was placed in the Crawford Chapel with access to the chancel by means of a door through the screen. Apart from re-voicing and one new rank on each division, the great and swell organs remained much as they were. Only the pedal organ was significantly enlarged by adding ranks of 4 ft and 2 ft pitch, a three rank mixture and 4 ft solo reed, and the trombone was extended to 8 ft and 4 ft pitch. Before 1901 there was a 4 ft stop and a three rank mixture on the pedal organ, both of which were discarded in 1901. The old choir organ was replaced by an unenclosed positif organ of authentic antique scale and with the part of the instrument that was new in 1963 was placed in the eastern bay of the Leigh Chapel, with the pedal gemshorn on display. The specification was drawn up by Mr A. G. D. Cutter, the organist in consultation with Mr R Mark Fairhead, of Hill, Norman & Beard Ltd., who was responsible for the tonal finishing of the organ.

The organists, some of whom were notable, include:

- Mr Coates 1623–1626

- Mr Betts 1714

- Mr Allan 1714–1717

- James Perrin 1717–1770

- John Langshaw 1770–1772

- Mr Barker 1772–1783

- James Entwistle 1784–1796

- Jane Entwistle 1796–1825

- Thomas Roby 1825–1839

- William Cooper 1839–1843

- Thomas Graham 1844–1867

- Walter Parratt 1868–1872 (later Master of the King's Music)

- Langdon Colborne 1875–1877 (later organist of Truro Cathedral)

- Alfred Alexander 1877–1888 (formerly organist of St. Michael's College, Tenbury)

- John W Potter 1889–1895

- Charles Harry Moody 1895–1899 (later organist of Holy Trinity Church, Coventry, and Ripon Cathedral)

- Edward Bairstow 1899–1906 (later organist of York Minster)

- Edgar Cyril Robinson 1906[9] – 1919 (formerly assistant organist at Lincoln Cathedral)

- Captain Percy W. de Courcy Smale 1919–1927

- William O Minay 1927–1943 (formerly assistant organist of Gloucester Cathedral, from 1946 organist of St Cuthbert's Church, Edinburgh)

- Frank E Bailey 1943–1948

- George Galloway 1949–1957

- Kenneth R Long 1958–1961

- A G David Cutter 1961–1994

- John Walton 1994–1999

- Karl Greenall 1999 – current

External features

To the south of the church in a triangular garden is a war memorial of 1925 designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, which is listed at Grade II*. It is in Portland stone with bronze plaques recording the names of those who fell in both world wars.[10] In and around the churchyard are structures that have been listed at Grade II. These are the boundary wall of the churchyard and two archways,[11] the gate piers at the north entrance to the churchyard,[12] railings encircling the church,[13] and two sections of the churchyard wall.[14][15]

Gallery

Detail from the south face

Detail from the south face Tower

Tower War memorial

War memorial

See also

Notes

- Brandwood et al. comment that the use of the Perpendicular style was very unusual at this time, and state that it was used "following the strong wishes of the parishioners to reproduce the style of the previous building".[7]

References

Citations

- All Saints, Wigan, Church of England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Church of All Saints, Wigan (1384556)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- History and Restoration, Wigan Parish Church, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 660–661.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Brandwood et al. 2012, p. 213.

- Brandwood et al. 2012, pp. 94–95.

- Wigan, All Saints, Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Dictionary of Organs and Organists. Fred. W. Thornsby. 1912

- Historic England, "War Memorial south of Church of All Saints with encircling railings, Wigan (1384562)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Boundary wall and two archways to west and south sides of churchyard of Church of All Saints, Wigan (1384557)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Gate piers at north entrance to churchyard of Church of All Saints, Wigan (1384558)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Railings encircling Church of All Saints to south and west, Wigan (1384559)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Section of churchyard wall to northeast of Church of All Saints, Wigan (1384560)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

- Historic England, "Section of churchyard wall of Church of All Saints on south, Wigan (1384561)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 29 May 2012

Sources

- Brandwood, Geoff; Austin, Tim; Hughes, John; Price, James (2012), The Architecture of Sharpe, Paley and Austin, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-84802-049-8

- Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006), Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10910-5