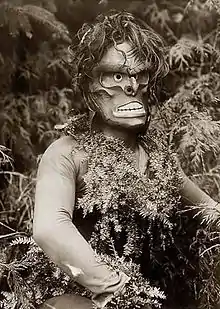

Wild man syndrome

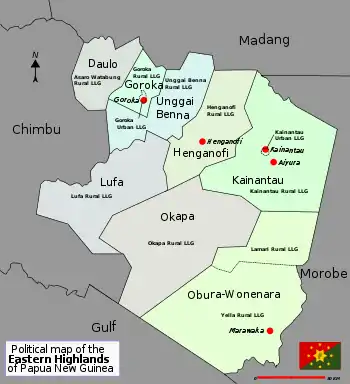

The wild man syndrome, also known as wild pig syndrome, is a culture-bound syndrome that affects the mental health of New Guinean males in which they become hyperactive, clumsy, kleptomaniacal, and “conveniently amnesic."[1] It is known in various languages of New Guinea as guria, longlong, or lulu.

"Wild-pig syndrome is a socially constructed disorder with an emotion classification of the Gururumba tribe. The illness is characterized by involuntary antisocial behavior, followed by situational amnesia and the resumption of normal life. After looting neighbors' homes, the tribesman (usually a recently married male) ventures into the forest for several days, returning without the stolen articles. Wild-pig attacks seem to occur when a man is unable to meet his financial obligations. Those who have undergone the episodes later receive special consideration from creditors. The Gururumba people insist the illness is transmitted by the ghosts of recently deceased tribe members."[2] Wild pig syndrome is limited by age and sex. It only occurs in males and only men who are 25 to 35 years of age. The syndrome is treated as a disease. The behavior is an action; however, it is not acknowledged as such by society or the individual that is experiencing the condition.

Historical and cultural background

Some theorists believe that emotions are produced by culture and are not biological. Their emotional diversity across cultures and the way individuals think is based on their social environment and on past and future experience and expectations. Wild Pig syndrome is unusual by Western standards; however, it is common and normal in the Gururumba tribe. This syndrome got its name from the occurrence of domesticated pigs going through a temporary state in which the pig will run wild. With appropriate measures the pig can return to the domesticated pig life among the villagers. This is similar to what happens to the Gururumba people thought to have this condition. They become aggressive, violent, stealing things of little importance, but they rarely hurt anyone and usually return to their normal life and routine. In most cases, they venture into the woods for several days; during their stay in the forest they destroy the stolen objects, then return to their village without any memory of the episode, only to be reminded of the event by other villagers. In more severe cases some individuals suffering from Wild Pig Syndrome have to be captured, restrained, and held over smoke until the individual returns to normal, as is done to a pig that has gone wild. Gururumba see this as a way of stress relief; however, Westerns would call this psychosis.[3] Attention should be drawn to the attitude of the community toward the wild man. "A feeling of expectant excitement is observable in the community; the actions of the wild man take on the character of a public spectical."[4] When news of its occurrence spreads, people drop what they are doing to simply watch the "wild man." The onlookers enjoy the instances when the wild man suddenly turns on the group and chases after one of them in an erratic and seemingly comic pursuit. The community responds to the wild man in somewhat the same way they would do at a comically frightening performance that is staged as entertainment. In all cases of Wild Pig Syndrome it is clear that the pattern is played out in a setting containing an audience such as ceremonial and festive occasions or gatherings of people to discuss some matter of general importance. In this highland environment there are unoccupied grasslands and forest in which the wild man could run wild in seclusion, but they never do. Another thing of importance of this condition is that nothing can be taken without the owner's permission, and if permission is granted, it is usually under the condition that the individual make some kind of reciprocation. Items of importance are closely guarded.

Symptoms

Physiological symptoms

The physiological symptoms of wild pig syndrome are increased respiratory rate and circulatory symptoms such as, a drop in skin temperature, sweating, trembling, rapid heart rate, dizziness, double vision, and aphasia.

Physical symptoms

One of the main symptoms of this condition is stealing objects of little value and taking them into the woods, never to be seen again. Some people believe the individual burns the objects, and other believe the individual destroys the objects piece by piece so they will never be found. The loss of the ability to speak and/or hear are main symptoms of this disorder. An individual suffering from Wild Pig Syndrome seems to have selective hearing; they do not hear much of what is going on around them unless it is concerned with specific objects of interest. Another important symptom found in all Wild Pig Syndrome cases is his treatment and attitude toward material objects. A large part of the individuals activity is centered around acquiring objects stolen from other individuals.

Motor activity disturbances

There are also motor activity disturbances such as hyperactivity, spontaneous attacks, shouting, scattering objects, and disrupting individuals gathered in groups. Someone suffering from this disorder may not always appear to be in control of their body. The individual may fall down, bump into things inadvertently, and have difficulty making movements with arms and legs. It has been noted that loss of bowel and bladder control can also be present.

Causes

The Gururumba tribe believes this syndrome is caused by being bitten by the spirit of a relative that has recently died. "They believe that this releases impulses suppressed by society and civilizations."[5] "There are several reports from Papua New Guinea that the ingestion of various parts of plants or fungi has produced "Wild-Man" syndrome." Among these are reports of eating certain leaves, bark, certain fruit, and certain fungi.[6] There is now increasing evidence that some forms of Wild Pig Syndrome is caused by nicotine poisoning from eating green tobacco leaves. Evidence for this can be seen when comparing the physical symptoms of this condition with Wild Pig Syndrome. Additional research has attributed the syndrome to be a cause of the stresses and obligations gained by young men shortly following marriage. These can include bad luck cropping and raising cattle, competing for prestige, and debts. [7]

Treatments

In most cases Wild Pig Syndrome will run its course, and no treatment is needed. In severe cases the individual will return to the village in the wild state, in which the individual is captured and a ceremony is held where the individual is restrained over a smoking fire until he returns to his normal state. Then the individual is rubbed down with liquefied pig fat; a small pig is killed in his name by a person of high status in the village, then afterward the individual is presented with a collection of cooked tubers and roots.

Criticisms

Some researchers have indicated that Wild Pig Syndrome typically occurs when a man cannot meet his financial obligations, so some critics see the syndrome as a scapegoat for the stress of reality, as creditors will work with an individual that has had a Wild Pig Syndrome attack.

Case study

Anthropologist Philip Newman describes witnessing the condition of wild pig syndrome and refers to the sufferer as "Gambiri." Gambiri was a man in his mid-thirties, married, with one small child and another on the way. One late afternoon Newman was sitting in the front door of his home talking to a group of children when Gambiri approached them carrying a small bowl in his hand. One of the children began asking him for food. Gambiri indicated that he did not have any food, but as usual the child did not accept this answer and snatched the bowl from Gambiri to see for himself. There were further demands for food and further denials by Gambiri. As tempers flared the child ran off with Gambiri's bowl with Gambiri chasing the child. After a while Gambiri appeared again at Mr. Newman's door. He was carrying a bow and a sheaf of arrows in one hand and a long-knife in the other. He ordered the children away from the door and came in the house. He then began rummaging about in Mr. Newman's personal belongings, and when Mr. Newman asked what he was doing he replied by demanding in a loud voice that Mr. Newman give back his bowl that he had stolen from him. When Mr. Newman stated that he had not taken his bowl, Gambiri shouted, "Maski", which is Neo-Melanesian for "no." Gambiri then saw a plastic pot used as a toilet and said in Neo-Melanesian, "There is my bowl. I can take it and throw it away in the forest. It is not that heavy." Gambiri was then gently guided outside by Mr. Newman's cook, who suggested that his missing bowl might be somewhere else. He then began trampling Mr. Newman's small flower garden. By this time a small crowd had gathered to watch and make comments on his behavior. When Gambiri made threats toward them they ran off laughing or screaming in mock terror. He grabbed a young girl and took away her bag that she was carrying. Then he demanded Mr. Newman to give him a piece of soap, which he gave to an onlooker, and a small knife that he gave Mr. Newman. He stated that the items were given to him by an Australian Patrol Officer for being a good worker on the government road. In about an hour his behavior became known to a wide audience. Others began calling out to other villages informing them of what was taking place. When a large audience gathered Gambiri hurried from place to place forcing his way into houses and demanding some small items as his, and engaged in aggressive verbalization. That evening he ran into the forest with his stolen bag full of stolen goods and was not seen again until the next morning. This time he was not carrying his bag. He spoke in the native language instead of Neo-Melanesian and did not exhibit any of the behavior he had during his Wild Pig attack.

References

- Bering, Dr. Jesse. "A Bad Case of Brain Fags". Slate. Dr. Jesse Bering. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Cattivera, Bert (2009-09-04). "Wild Pigs Attack". The Eccentrist. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- LeDoux, Joseph. "The Emotional Brain" (PDF). The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Ace Centre. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Newman, Philip (Feb 1964). ""Wild Man" Behavior in a New Guinea Highlands Community". American Anthropologist. New Series. 66 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.1.02a00010. JSTOR 669077. S2CID 162290971.

- Griffiths, Paul (1997). What Emotions Really Are. London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30872-2.

- Thomas, Benjamin. "Nicotinism, Colonisalism, & The Wild Man". The Ethnobotany & Anthropology Research Page. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Pelto, Pertti J. (1967). "Psychological Anthropology". Biennial Review of Anthropology. 5: 140–208. ISSN 0067-8503. JSTOR 2949210.

Further reading

- Cattivera, Bert. 2009. Wild Pigs Attack. Accessed July 11, 2011, from The Eccentrist:.

- Rainydaypaperback. 2008. Types of Insanity Around the World. Accessed July 18, 2011, from the Qondio Global:

- Newman, Philip L. 1965. "Knowing The Gururumba" Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 110 pp. Accessed From "American Anthropologist" 1967 Volume 69, Issue 1, pg. 112, PDF

- Newman, Philip (1996). "Gururumba" Accessed July 21, 2011, from online Encyclopedia.