Dangling pointer

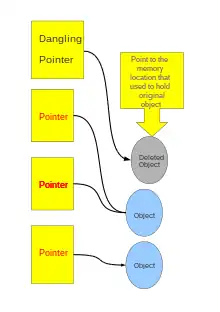

Dangling pointers and wild pointers in computer programming are pointers that do not point to a valid object of the appropriate type. These are special cases of memory safety violations. More generally, dangling references and wild references are references that do not resolve to a valid destination.

Dangling pointers arise during object destruction, when an object that has an incoming reference is deleted or deallocated, without modifying the value of the pointer, so that the pointer still points to the memory location of the deallocated memory. The system may reallocate the previously freed memory, and if the program then dereferences the (now) dangling pointer, unpredictable behavior may result, as the memory may now contain completely different data. If the program writes to memory referenced by a dangling pointer, a silent corruption of unrelated data may result, leading to subtle bugs that can be extremely difficult to find. If the memory has been reallocated to another process, then attempting to dereference the dangling pointer can cause segmentation faults (UNIX, Linux) or general protection faults (Windows). If the program has sufficient privileges to allow it to overwrite the bookkeeping data used by the kernel's memory allocator, the corruption can cause system instabilities. In object-oriented languages with garbage collection, dangling references are prevented by only destroying objects that are unreachable, meaning they do not have any incoming pointers; this is ensured either by tracing or reference counting. However, a finalizer may create new references to an object, requiring object resurrection to prevent a dangling reference.

Wild pointers arise when a pointer is used prior to initialization to some known state, which is possible in some programming languages. It also calls as Uninitialized pointer. They show the same erratic behavior as dangling pointers, though they are less likely to stay undetected because many compilers will raise a warning at compile time if declared variables are accessed before being initialized.[1]

Cause of dangling pointers

In many languages (e.g., the C programming language) deleting an object from memory explicitly or by destroying the stack frame on return does not alter associated pointers. The pointer still points to the same location in memory even though it may now be used for other purposes.

A straightforward example is shown below:

{

char *dp = NULL;

/* ... */

{

char c;

dp = &c;

}

/* c falls out of scope */

/* dp is now a dangling pointer */

}

If the operating system is able to detect run-time references to null pointers, a solution to the above is to assign 0 (null) to dp immediately before the inner block is exited. Another solution would be to somehow guarantee dp is not used again without further initialization.

Another frequent source of dangling pointers is a jumbled combination of malloc() and free() library calls: a pointer becomes dangling when the block of memory it points to is freed. As with the previous example one way to avoid this is to make sure to reset the pointer to null after freeing its reference—as demonstrated below.

#include <stdlib.h>

void func()

{

char *dp = malloc(A_CONST);

/* ... */

free(dp); /* dp now becomes a dangling pointer */

dp = NULL; /* dp is no longer dangling */

/* ... */

}

An all too common misstep is returning addresses of a stack-allocated local variable: once a called function returns, the space for these variables gets deallocated and technically they have "garbage values".

int *func(void)

{

int num = 1234;

/* ... */

return #

}

Attempts to read from the pointer may still return the correct value (1234) for a while after calling func, but any functions called thereafter may overwrite the stack storage allocated for num with other values and the pointer would no longer work correctly. If a pointer to num must be returned, num must have scope beyond the function—it might be declared as static.

Manual deallocation without dangling reference

Antoni Kreczmar (1945–1996) has created a complete object management system which is free of dangling reference phenomenon.[2] A similar approach was proposed by Fisher and LeBlanc[3] under the name Locks-and-keys.

Cause of wild pointers

Wild pointers are created by omitting necessary initialization prior to first use. Thus, strictly speaking, every pointer in programming languages which do not enforce initialization begins as a wild pointer.

This most often occurs due to jumping over the initialization, not by omitting it. Most compilers are able to warn about this.

int f(int i)

{

char *dp; /* dp is a wild pointer */

static char *scp; /* scp is not a wild pointer:

* static variables are initialized to 0

* at start and retain their values from

* the last call afterwards.

* Using this feature may be considered bad

* style if not commented */

}

Security holes involving dangling pointers

Like buffer-overflow bugs, dangling/wild pointer bugs frequently become security holes. For example, if the pointer is used to make a virtual function call, a different address (possibly pointing at exploit code) may be called due to the vtable pointer being overwritten. Alternatively, if the pointer is used for writing to memory, some other data structure may be corrupted. Even if the memory is only read once the pointer becomes dangling, it can lead to information leaks (if interesting data is put in the next structure allocated there) or to privilege escalation (if the now-invalid memory is used in security checks). When a dangling pointer is used after it has been freed without allocating a new chunk of memory to it, this becomes known as a "use after free" vulnerability.[4] For example, CVE-2014-1776 is a use-after-free vulnerability in Microsoft Internet Explorer 6 through 11[5] being used by zero-day attacks by an advanced persistent threat.[6]

Avoiding dangling pointer errors

In C, the simplest technique is to implement an alternative version of the free() (or alike) function which guarantees the reset of the pointer. However, this technique will not clear other pointer variables which may contain a copy of the pointer.

#include <assert.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

/* Alternative version for 'free()' */

static void safefree(void **pp)

{

/* in debug mode, abort if pp is NULL */

assert(pp);

/* free(NULL) works properly, so no check is required besides the assert in debug mode */

free(*pp); /* deallocate chunk, note that free(NULL) is valid */

*pp = NULL; /* reset original pointer */

}

int f(int i)

{

char *p = NULL, *p2;

p = malloc(1000); /* get a chunk */

p2 = p; /* copy the pointer */

/* use the chunk here */

safefree((void **)&p); /* safety freeing; does not affect p2 variable */

safefree((void **)&p); /* this second call won't fail as p is reset to NULL */

char c = *p2; /* p2 is still a dangling pointer, so this is undefined behavior. */

return i + c;

}

The alternative version can be used even to guarantee the validity of an empty pointer before calling malloc():

safefree(&p); /* i'm not sure if chunk has been released */

p = malloc(1000); /* allocate now */

These uses can be masked through #define directives to construct useful macros (a common one being #define XFREE(ptr) safefree((void **)&(ptr))), creating something like a metalanguage or can be embedded into a tool library apart. In every case, programmers using this technique should use the safe versions in every instance where free() would be used; failing in doing so leads again to the problem. Also, this solution is limited to the scope of a single program or project, and should be properly documented.

Among more structured solutions, a popular technique to avoid dangling pointers in C++ is to use smart pointers. A smart pointer typically uses reference counting to reclaim objects. Some other techniques include the tombstones method and the locks-and-keys method.[3]

Another approach is to use the Boehm garbage collector, a conservative garbage collector that replaces standard memory allocation functions in C and C++ with a garbage collector. This approach completely eliminates dangling pointer errors by disabling frees, and reclaiming objects by garbage collection.

In languages like Java, dangling pointers cannot occur because there is no mechanism to explicitly deallocate memory. Rather, the garbage collector may deallocate memory, but only when the object is no longer reachable from any references.

In the language Rust, the type system has been extended to include also the variables lifetimes and resource acquisition is initialization. Unless one disables the features of the language, dangling pointers will be caught at compile time and reported as programming errors.

Dangling pointer detection

To expose dangling pointer errors, one common programming technique is to set pointers to the null pointer or to an invalid address once the storage they point to has been released. When the null pointer is dereferenced (in most languages) the program will immediately terminate—there is no potential for data corruption or unpredictable behavior. This makes the underlying programming mistake easier to find and resolve. This technique does not help when there are multiple copies of the pointer.

Some debuggers will automatically overwrite and destroy data that has been freed, usually with a specific pattern, such as 0xDEADBEEF (Microsoft's Visual C/C++ debugger, for example, uses 0xCC, 0xCD or 0xDD depending on what has been freed[7]). This usually prevents the data from being reused by making it useless and also very prominent (the pattern serves to show the programmer that the memory has already been freed).

Tools such as Polyspace, TotalView, Valgrind, Mudflap,[8] AddressSanitizer, or tools based on LLVM[9] can also be used to detect uses of dangling pointers.

Other tools (SoftBound, Insure++, and CheckPointer) instrument the source code to collect and track legitimate values for pointers ("metadata") and check each pointer access against the metadata for validity.

Another strategy, when suspecting a small set of classes, is to temporarily make all their member functions virtual: after the class instance has been destructed/freed, its pointer to the Virtual Method Table is set to NULL, and any call to a member function will crash the program and it will show the guilty code in the debugger.

References

- "Warning Options - Using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC)".

- Gianna Cioni, Antoni Kreczmar, Programmed deallocation without dangling reference, Information Processing Letters, v. 18, 1984, pp. 179–185

- C. N. Fisher, R. J. Leblanc, The implementation of run-time diagnostics in Pascal , IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 6(4):313–319, 1980.

- Dalci, Eric; anonymous author; CWE Content Team (May 11, 2012). "CWE-416: Use After Free". Common Weakness Enumeration. Mitre Corporation. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - "CVE-2014-1776". Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE). 2014-01-29. Archived from the original on 2017-04-30. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Chen, Xiaobo; Caselden, Dan; Scott, Mike (April 26, 2014). "New Zero-Day Exploit targeting Internet Explorer Versions 9 through 11 Identified in Targeted Attacks". FireEye Blog. FireEye. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- Visual C++ 6.0 memory-fill patterns

- Mudflap Pointer Debugging

- Dhurjati, D. and Adve, V. Efficiently Detecting All Dangling Pointer Uses in Production Servers