Wilkinson County, Mississippi

Wilkinson County is a county located in the southwest corner of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of 2020, its population was 8,587.[1] Its county seat is Woodville.[2] Bordered by the Mississippi River on the west, the county is named for James Wilkinson, a Revolutionary War military leader and first governor of the Louisiana Territory after its acquisition by the United States in 1803.

Wilkinson County | |

|---|---|

Left to right: Clark Creek and Wilkinson County Courthouse | |

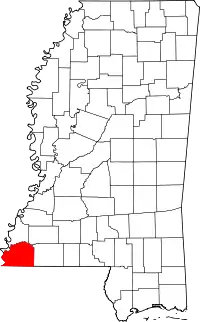

Location within the U.S. state of Mississippi | |

Mississippi's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 31°10′N 91°19′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1802 |

| Named for | James Wilkinson |

| Seat | Woodville |

| Largest town | Centreville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 688 sq mi (1,780 km2) |

| • Land | 678 sq mi (1,760 km2) |

| • Water | 9.7 sq mi (25 km2) 1.4% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 8,587 |

| • Density | 12/sq mi (4.8/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 3rd |

| Website | www |

History

After Indian Removal in the 19th century, European-American settlers rapidly developed cotton plantations along the Mississippi River, which forms the western border. The intensive cultivation depended on the labor of numerous enslaved African Americans; in the early 19th century, more than a million slaves were relocated to the Deep South from the Upper South in a major forced migration. The population of this county quickly became majority black as enslaved workers were brought in to develop plantations. Much of the bottomlands and interior were undeveloped frontier until after the American Civil War.

The West Feliciana Railroad was later built to help get the cotton commodity crop to market. Some planters got wealthy during the antebellum years and built fine mansions in the county seat of Woodville, Mississippi. Jane and Samuel Emory Davis moved here in 1812 with their several children, and lived at a plantation near Woodville. Their youngest son, Jefferson Davis, attended the Wilkinson Academy in Woodville for two years before going to Kentucky to another school.[3]

After the Civil War, freedmen and planters negotiated new working arrangements. Sharecropping became widespread. Although cotton continued as the commodity crop, a long agricultural depression kept prices low.

Following Reconstruction, white violence against blacks increased through the later decades of the 19th century and into the early 20th century. According to 2017 data compiled in Lynching in America (2015-2017), some nine lynchings of African Americans were recorded in Wilkinson County.[4]

The peak of population in the county was reached in 1900, after which many blacks left in the Great Migration to the North and Midwest. The county has continued to have a black majority population.

In the early 20th century the boll weevil infestation destroyed much of the cotton crops, and mechanization caused a further loss of agricultural jobs. The exit of many African Americans from the state did not change the state's exclusion of African Americans from politics. They were not enabled to vote until after passage of the federal Voting Rights Act in 1965 and its enforcement. Cotton cultivation was revived, but it is produced on a highly mechanized, industrial scale.

Southwest Mississippi was an area of continuing white violence against blacks during the Civil Rights Movement. In February 1964, the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan officially formed. Clifton Walker, 37, a married father of five and employee of International Paper Company in Natchez, who was not politically active, was killed in an ambush on Poor House Road near his home. The evidence showed there had been a crowd of shooters on both sides of the road.[5] This lynching cold case has never been solved, although it was among numerous ones that the FBI was investigating since 2007, before the Donald Trump administration ended the effort in 2018.

Timber has been harvested and processed in the county as a new commodity crop. The population of the rural county has continued to decline because of lack of jobs. It is still majority African American. Towns have started to develop heritage tourism to attract more visitors.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 688 square miles (1,780 km2), of which 678 square miles (1,760 km2) is land and 9.7 square miles (25 km2) (1.4%) is water.[6]

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Adams County (north)

- Franklin County (northeast)

- Amite County (east)

- East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana (southeast)

- West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana (south)

- Concordia Parish, Louisiana (west)

National protected area

- Homochitto National Forest (part)

State protected area

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 5,068 | — | |

| 1820 | 9,718 | 91.8% | |

| 1830 | 11,686 | 20.3% | |

| 1840 | 14,193 | 21.5% | |

| 1850 | 16,914 | 19.2% | |

| 1860 | 15,933 | −5.8% | |

| 1870 | 12,705 | −20.3% | |

| 1880 | 17,815 | 40.2% | |

| 1890 | 17,592 | −1.3% | |

| 1900 | 21,453 | 21.9% | |

| 1910 | 18,075 | −15.7% | |

| 1920 | 15,319 | −15.2% | |

| 1930 | 13,957 | −8.9% | |

| 1940 | 15,955 | 14.3% | |

| 1950 | 14,116 | −11.5% | |

| 1960 | 13,235 | −6.2% | |

| 1970 | 11,099 | −16.1% | |

| 1980 | 10,021 | −9.7% | |

| 1990 | 9,678 | −3.4% | |

| 2000 | 10,312 | 6.6% | |

| 2010 | 9,878 | −4.2% | |

| 2020 | 8,587 | −13.1% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 8,315 | −3.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] 1790-1960[9] 1900-1990[10] 1990-2000[11] 2010-2013[12] | |||

Population

Wilkinson County had a population of 8,587 people, 3,170 households, and 1,843 families at the 2020 United States census.[1]

Race

| Race/ethnicity | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 2,525 | 29.4% |

| Black or African American | 5,764 | 67.12% |

| Native American | 16 | 0.19% |

| Asian | 8 | 0.09% |

| Other/Mixed | 204 | 2.38% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 70 | 0.82% |

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Wilkinson County's racial and ethic makeup was predominantly Black and African American in 2020.[1] The total racial and ethnic composition at the 2020 census was 67.12% Black and African American, 29.4% non-Hispanic white, 0.19% Native American, 0.09% Asian, 2.38% multiracial or other race or ethnicity, and 0.82% Hispanic or Latin American of any race.

Income

In 2010, the American Community Survey estimated the county had a median household income of $28,066.[13] At the 2020 American Community Survey, its median household income increased to $30,760; the median monthly housing costs were $419. In 2020, the county had a mean income of $46,538, and married-couple families had a median income of $50,227 while non-family households averaged $27,468.[14]

Education

Wilkinson County School District serves the county.[15] Prior to 1970, when a federal court ruling forced the schools to integrate, the county maintained a separate and highly inferior educational system for Black students. When the schools were finally integrated, all but two white students initially chose to attend Wilkinson County Christian Academy, which was established in 1969 as a segregation academy,[16] or other private schools rather than attend school with Black students.[17][18] Barnard Waites, the superintendent of the public school system sent his own child to Wilkinson County Christian Academy, and harshly criticized the white parents who exposed their children to the "all negro environment" of Wilkinson County Training School.[19]

Communities

Towns

- Centreville (partly in Amite County)

- Crosby (partly in Amite County)

- Woodville (county seat)

Unincorporated communities

Ghost towns

Notable people

- Regina Barrow (born 1966), Louisiana state senator from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, since 2016; former state representative from 2005 to 2016; native of Wilkinson County[20]

- Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America; grew up at Rosemont plantation just east of Woodville

- Anne Moody (1940-2015), civil rights activist and author

- Edward Grady Partin (1924–1990), Teamsters Union business agent in Baton Rouge, native of Woodville

- William Grant Still, African-American classical composer and Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame inductee was born in Woodville in 1895

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 1,324 | 32.08% | 2,749 | 66.61% | 54 | 1.31% |

| 2016 | 1,318 | 31.25% | 2,857 | 67.73% | 43 | 1.02% |

| 2012 | 1,415 | 29.16% | 3,412 | 70.31% | 26 | 0.54% |

| 2008 | 1,560 | 30.36% | 3,534 | 68.77% | 45 | 0.88% |

| 2004 | 1,563 | 35.64% | 2,794 | 63.72% | 28 | 0.64% |

| 2000 | 1,423 | 34.72% | 2,551 | 62.25% | 124 | 3.03% |

| 1996 | 1,016 | 24.77% | 2,807 | 68.43% | 279 | 6.80% |

| 1992 | 1,399 | 28.29% | 3,210 | 64.91% | 336 | 6.79% |

| 1988 | 1,528 | 36.18% | 2,678 | 63.41% | 17 | 0.40% |

| 1984 | 1,722 | 39.28% | 2,627 | 59.92% | 35 | 0.80% |

| 1980 | 1,442 | 32.04% | 2,981 | 66.24% | 77 | 1.71% |

| 1976 | 1,273 | 33.11% | 2,514 | 65.38% | 58 | 1.51% |

| 1972 | 1,608 | 52.65% | 1,409 | 46.14% | 37 | 1.21% |

| 1968 | 272 | 6.94% | 2,144 | 54.71% | 1,503 | 38.35% |

| 1964 | 1,473 | 93.46% | 103 | 6.54% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 174 | 14.24% | 216 | 17.68% | 832 | 68.09% |

| 1956 | 240 | 28.20% | 260 | 30.55% | 351 | 41.25% |

| 1952 | 699 | 55.39% | 563 | 44.61% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 21 | 2.40% | 43 | 4.92% | 810 | 92.68% |

| 1944 | 80 | 8.48% | 863 | 91.52% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 46 | 4.66% | 942 | 95.34% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 21 | 2.66% | 767 | 97.09% | 2 | 0.25% |

| 1932 | 18 | 2.16% | 813 | 97.48% | 3 | 0.36% |

| 1928 | 73 | 8.69% | 767 | 91.31% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 40 | 10.13% | 355 | 89.87% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1920 | 15 | 3.46% | 416 | 96.07% | 2 | 0.46% |

| 1916 | 8 | 1.69% | 460 | 97.46% | 4 | 0.85% |

| 1912 | 8 | 1.92% | 379 | 90.89% | 30 | 7.19% |

References

- "2020 Race and Population Totals". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Strode, Hudson (1955). Jefferson Davis, Volume I: American Patriot. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, pp. 11-27

- "Lynching in America, Supplement: Lynching by County, 3rd edition, 2017, p.7; accessed 07 June 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- Frank Morris, "Cold Case: Ambush on Poor House Road: The 1964 murder of Clifton Walker", Concordia Sentinel, 22 July 2012; accessed 07 June 2018

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Clark Creek". MDWFP Parks & Destinations. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- "2010 Income Estimates". data.census.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- "2020 Income Estimates". data.census.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Wilkinson County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved July 31, 2022. - Text list

- Dangerfileld, Celnisha. "Mapping Race, School Segregation, and Black Identities in Woodville, Mississippi: A Case Study of a Rural Community". Journal of Rural Community Psychology - Mapping Race. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009.

- "School desegregation in Woodville, Mississippi". Globe-Gazette. January 6, 1970. p. 1.

- "Integration in Woodville Schools cont". Globe-Gazette. January 6, 1970. p. 2.

- Wooten, James T (January 12, 1970). "A new day ends public segregated schools in Mississippi". New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- "Regina Ashford Barrow". Project Vote Smart. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

External links

- Official website of Wilkinson County

Media related to Wilkinson County, Mississippi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wilkinson County, Mississippi at Wikimedia Commons