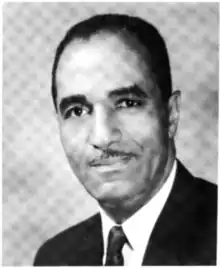

William B. Bryant

William Benson Bryant (September 18, 1911 – November 13, 2005) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia and served as the first African-American Chief Judge of the court.

William Benson Bryant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Senior Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia | |

| In office January 31, 1982 – November 13, 2005 | |

| Chief Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia | |

| In office 1977–1981 | |

| Preceded by | William Blakely Jones |

| Succeeded by | John Lewis Smith Jr. |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia | |

| In office August 11, 1965 – January 31, 1982 | |

| Appointed by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | David Andrew Pine |

| Succeeded by | Thomas F. Hogan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Benson Bryant September 18, 1911 Wetumpka, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | November 13, 2005 (aged 94) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Education | Howard University (AB, LLB) |

Early life, education and military service

Born in Wetumpka, Alabama, Bryant attended local schools. His parents encouraged his education and he studied political science at Howard University, a historically black college, graduating with an Artium Baccalaureus degree in 1932. Bryant earned his Bachelor of Laws from Howard University School of Law in 1936, graduating first in his class.[1] Following law school, Bryant served as chief research assistant to Ralph Bunche, then Chair of the Department of Political Science at Howard, while Bunche worked with Gunnar Myrdal on his 1944 study of American race relations An American Dilemma.[2] Bryant served as an officer in the United States Army during World War II, from 1943 to 1947, reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel.[3]

Legal career

Bryant entered private practice in Washington, D.C., in 1948 and became a named partner at the firm headed by Charles Hamilton Houston, who had been dean of Howard Law School and served as legal counsel for the NAACP. At the time, the D.C. bar was still closed to African Americans.[1] Bryant left private practice to serve as an Assistant United States Attorney in the District of Columbia from 1951 to 1954. He was one of the first black prosecutors in federal court in the capital.[1] Returning to private practice in 1954, Bryant handled a number of prominent cases as a criminal defense lawyer. In 1957, he took a case to the United States Supreme Court, Mallory v. United States.[4] In the case, Andrew Roosevelt Mallory, 19, had confessed to rape after 7½ hours of interrogation in a police station. He was convicted and sentenced to death. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court overturned Mallory's conviction because his arraignment was not accomplished "without unnecessary delay," violating the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.[4] The case's holding formed the basis of the "McNabb-Mallory rule," a United States rule of evidence superseded by the broader protections later outlined by the Supreme Court in Miranda v. Arizona. While in private practice, Bryant also served as a law professor at Howard.[3]

Federal judicial service

Bryant was nominated by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 12, 1965, to a seat on the United States District Court for the District of Columbia vacated by Judge David Andrew Pine. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on August 11, 1965, and received his commission the same day. He served as the first African American Chief Judge of the court from 1977 to 1981. He assumed senior status on January 31, 1982, and continued to hear cases until just a few months before his death.[3] His service was terminated on November 13, 2005, due to his death in Washington, D.C.[1]

Notable cases

While on the bench, Judge Bryant presided over numerous high-profile cases. In May 1972, he threw out the results of the 1969 United Mine Workers of America union elections, after allegations of fraud and the murder of losing candidate Joseph Yablonski.[5] Bryant scheduled a new election to be held in December 1972 and required that the United States Department of Labor oversee the election to ensure fairness. The winner of the disputed vote, W. A. Boyle, was defeated in the ensuing election; he was later convicted of Yablonski's murder.[6]

Bryant held in 1975 that Washington's height requirement for firefighters was illegal, in 1979 that the government's searches of the offices of the Church of Scientology were unconstitutional, and was the first judge to order President Richard Nixon to turn over his audiotapes in connection with civil lawsuits in the Watergate affair.[7] In Inmates of D.C. Jail v. Jackson, he found that conditions in D.C. jails violated the Eighth Amendment's ban on "cruel and unusual punishment." He said that he had listened to corrections officials' promises of improvement "since the Big Dipper was a thimble."[7]

Honors

In 2003, his fellow judges at the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia had requested that the new annex at the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse be named after him. This proposal was signed into law by President George W. Bush two days before Judge Bryant's death in 2005.[1]

See also

References

- "Pioneering D.C. Judge Beat Racial Odds With Wisdom". Washington Post. November 15, 2005.

- Norton, Eleanor (2004), "Judge William B. Bryant Annex to the E. Barrett Prettyman Federal Building and United States Courthouse", Congressional Record, vol. 150, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 753

- William Benson Bryant at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Mallory v. United States, The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, retrieved September 15, 2011

- Hodgson v. United Mine Workers of America, 344 F. Supp. 17 (D.D.C. 1972).

- "The Yablonski Legacy". Harvard Crimson. March 20, 1976.

- "William Bryant, Top Lawyer and Trailblazing Judge, 94, Dies". New York Times. November 16, 2005.

Sources

- William Benson Bryant at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.