William B. Cushing

William Barker Cushing (4 November 1842 – 17 December 1874) was an officer in the United States Navy, best known for sinking the CSS Albemarle during a daring nighttime raid on 27 October 1864, for which he received the Thanks of Congress. Cushing was the younger brother of Medal of Honor recipient Alonzo Cushing. As a result, the Cushing family is the only family in American history to have a member buried at more than one of the United States Service Academies.

William B. Cushing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | William Barker Cushing |

| Born | 4 November 1842 Delafield, Territory of Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | 17 December 1874 (aged 32) Washington D.C., U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1861–1874 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | |

| Wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | Thanks of Congress |

| Relations |

|

Biography

Early life

Cushing was born in Delafield, Wisconsin, and was the youngest of four brothers and had two sisters. After the death of his father when he was still a young child, the family relocated to Fredonia, New York. He was expelled from the United States Naval Academy, just before graduation, for pranks and poor scholarship. At the outbreak of the American Civil War, however, he pleaded his case to United States Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles himself, was reinstated and went on to acquire a distinguished record, frequently volunteering for the most hazardous missions. "His heroism, good luck and coolness under fire were legendary."[1]

Civil War

Cushing saw action during the Battle of Hampton Roads and at Fort Fisher,[2] among many others. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1862, and to commander in 1872.[3] Two of his brothers died in uniform, Alonzo H. Cushing in the Battle of Gettysburg, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor,[4] and Howard B. Cushing, while fighting the Chiricahua Apaches in 1871.[5] His eldest brother, Milton, served in the Navy as a paymaster.[6]

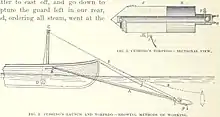

It was Cushing's daring plan and its successful execution against the Confederacy's ironclad ram CSS Albemarle that defined his military career. The powerful ironclad dominated the Roanoke River and the approaches to Plymouth through the summer of 1864. By autumn, the U.S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done. The U.S. Navy considered various ways to destroy Albemarle, including two daring plans submitted by Lieutenant Cushing. They finally approved one of his plans and authorized him to locate two small steam launches that might be fitted with spar torpedoes.

Cushing discovered two 30-foot (9.1 m) picket boats under construction in New York and acquired them for his mission.[7] On each he mounted a 12-pound Dahlgren howitzer and a 14-foot (4.3 m) spar projecting into the water from its bow. One of the boats was lost at sea during the voyage from New York to Norfolk, Virginia, but the other arrived safely with its crew of seven officers and men at the mouth of the Roanoke. There, the steam launch's spar was fitted with a lanyard-detonated torpedo.

_(14578563567).jpg.webp)

On the night of 27–28 October 1864, Cushing and his men began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a schooner anchored to the wreck of USS Southfield. When both boats, under the cover of darkness, slipped past the schooner undetected, Cushing decided to use all 22 of his men and the element of surprise to capture Albemarle.[8]

As they approached the Confederate docks, their luck turned and even though under the cover of darkness they were spotted by a guard dog. They came under heavy sentry fire from both the shore and aboard Albemarle. As they closed with Albemarle, they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating log booms. The logs, however, had been in the water for many months and were covered with heavy slime. The steam launch rode up and then over them without difficulty. When her spar was fully against the ironclad's hull, Cushing stood up in the bow and detonated the torpedo's explosive charge.[9]

The explosion threw everyone aboard the steam launch into the water. Recovering quickly, Cushing stripped off his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid until daylight. That afternoon, having avoided detection by Confederate search parties, he stole a small skiff and quietly paddled down-river to rejoin the Union forces at the river's mouth. Of the other men in Cushing's boat, William Houghtman escaped, John Woodman and Richard Higgins were drowned, and 11 were captured.[9]

Cushing's daring commando raid blew a hole in Albemarle's hull at the waterline "big enough to drive a wagon in." She sank immediately in the six feet of water below her keel, settling into the heavy bottom mud, leaving the upper armored casemate mostly dry and the ironclad's large Stainless Banner battle ensign flying from its flag staff, where it was eventually captured as a Union prize.[9][10]

Postbellum

After the Civil War, Cushing served in both the Pacific and Asiatic Squadrons; he was the executive officer of the USS Lancaster and commanded the USS Maumee. He also served as ordnance officer in the Boston Navy Yard.

Before taking command of USS Maumee, while he was on leave at home in Fredonia, Cushing met his sister's friend, Katherine Louise Forbes. 'Kate', as she was known, would sit and listen for hours to William's stories of adventure. Cushing asked her to marry him on 1 July 1867. Unfortunately, he received orders and was gone before a ceremony could take place. On 22 February 1870, Cushing and Forbes married. Their first daughter, Marie Louise, was born on 1 December 1871.

On 31 January 1872, he was promoted to the rank of commander, becoming the youngest up to that time to attain that rank in the Navy. Two weeks later he was detached to await orders. Weeks of waiting turned into months, but no word came. He had given up hope of another sea command, when early in June 1873, Cushing had an offer to take command of USS Wyoming. He took command of his new ship on 11 July 1873.[11]

He commanded Wyoming with his typical flair for being where the action was, performing daring and courageous acts. Wyoming's boilers broke down twice, and in April she was ordered to Norfolk for extensive repairs. On 24 April, Cushing was detached and put on a waiting list for reassignment. He believed that he would be given Wyoming again when she was ready for duty, but in truth, his ill-health would not permit him to command another vessel.[11]

Cushing returned to Fredonia to see his new daughter, Katherine Abell, who had been born on 11 October 1873. His wife was shocked to see the condition of her husband. His health was in apparent decline. Kate remarked to William's mother that he looked to be a man of sixty instead of his thirty-one years. Cushing had begun having severe attacks of pain in his hip as early as just after the sinking of the Albemarle.

None of the doctors he saw were able to make a diagnosis. The term "sciatica" was used in those days without regard to cause for any inflammation of the sciatic nerve, or any pain in the region of the hip. Cushing may have had a ruptured intervertebral disc. He had suffered enough shocks to dislocate half a dozen vertebrae, and with the passage of time they came to bear more and more heavily upon the nerve. On the other hand, he may have been suffering from tuberculosis of the hip bone, or cancer of the prostate gland. There was nothing to be done and Cushing continued to suffer.[12]

He was given the post of executive officer of the Washington Navy Yard. He spent the summer of 1874 pretending to be happy with his inactive role. He played with his children and enjoyed their company. On 25 August, he was made senior aide at the yard; in the fall he amused himself by taking an active interest in the upcoming congressional elections.[6]

On Thanksgiving Day, William, Kate and his mother went to church in the morning.[13] That night, the pain in Cushing's back was worse than it had ever been and he could not sleep. The following Monday he dragged himself to the Navy Yard. Kate sent Lieutenant Hutchins, once of the Wyoming crew and now Cushing's aide, to bring his superior home. She feared that he wouldn't last the day. True to his nature, Cushing stayed at the yard until after nightfall, and went right to bed when he got home. He would not rise again. The pain was constant and terrible. He was given injections of morphine, but that only dulled the pain a little.[14]

On 8 December, it became impossible to care for Cushing at home, and he was removed to St. Elizabeths Hospital. His family visited him often, but he seldom recognized them. Cushing died on 17 December 1874, in the presence of his wife and mother. He was buried on 8 January 1875, at Bluff Point, at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis.[14]

Legacy

Cushing's grave is marked by a large, monumental casket made of marble, on which in relief, are Cushing's hat, sword, and coat. On one side of the stone the word "Albemarle" is cut and on the other side, "Fort Fisher".[15]

Five ships in the U.S. Navy have been named USS Cushing after him.[16][17] The most recent one, the USS Cushing (DD-985), was decommissioned in September 2005.[18]

Cushing has a portrait of him in full dress uniform hanging in Memorial Hall at the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis.[19] Nearly all of the other portraits in the hall are of admirals.[20] A monument that honors Alonzo, William, and Howard Cushing is located at Cushing Memorial Park in Delafield, Wisconsin.[21]

See also

Notes

- Tsouras, Peter G. (2010). A Rainbow of Blood: The Union in Peril – An Alternate History. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 418. ISBN 9781597976152.

- Edwards 1898, pp. 190–192.

- Stempel 2011, p. 211.

- "Lt. Alonzo Cushing, Hero of Gettysburg, Awarded Medal of Honor". NPR.org. 6 November 2014.

- Utley, Robert M. (2012). Geronimo. Yale University Press. pp. 1680–1681. ISBN 9780300189001.

- Parker, David Bigelow (1912). A Chautauqua Boy in '61 and Afterward: Reminiscences. Small, Maynard. p. 84.

- Battles and Leaders Vol 4, pp. 634

- Stempel 2011, p. 203.

- Stempel 2011, p. 204.

- Edwards 1898, p. 246.

- Schneller 2004, pp. 98–101.

- McQuiston 2012, pp. 155–156.

- McQuiston 2012, p. 35.

- Carter, Alden R. (2009). The Sea Eagle: The Civil War Memoir of LCdr. William B. Cushing, U.S.N. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 9780742599963.

- Arbuthnot, Nancy (2012). Guiding Lights: Monuments and Memorials at the U.S. Naval Academy. Naval Institute Press. p. 72. ISBN 9781612512426.

- Sizer, Mona D. (2009). The Glory Guys: The Story of the U.S. Army Rangers. Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 117–118. ISBN 9781589794764.

- Hughes, Wayne (2015). The U.S. Naval Institute on Naval Tactics: The U.S. Naval Institute Wheel Book Series. Naval Institute Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781612518916.

- Polmar, Norman; Cavas, Christopher P. (2009). Navy's Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Admirable Admirals, Sleek Submarines, and Oceanic Oddities. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 9781597976558.

- "Naval History and Heritage Command".

- "WISNAPACushing Award |". wisconsin.usnaparents.net. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Downs, John Phillips (1921). History of Chautauqua County New York and its People. Ripol Classic. p. 357. ISBN 9785872000877.

Bibliography

- Campbell, R. T. (1997). Rebel Fire: Exploits of the Confederate Navy. Burd Street Press. ISBN 1572490462.

- Cushing, William B. (1888). "The Destruction of the "Albemarle"". The Century Magazine. The Career of the Confederate Ram "Albemarle". Vol. XXXVI. pp. 386–393. OCLC 21247159.

- Edwards, E. M. H. (1898). Commander William Barker Cushing, of the United States Navy. London & New York: F. Tennyson Neely Publisher. hdl:2027/hvd.hx4mfu.

- Elliot, Gilbert (1888), "Her Construction and Service", The Century Magazine, The Career of the Confederate Ram "Albemarle", XXXVI: 374–380, OCLC 21247159

- Elliott, Robert G. (1994). Ironclad of the Roanoke: Gilbert Elliott's Albemarle. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing. ISBN 0-942597-63-X.

- Hinds, John W. (2002). The Hunt for the Albemarle: Anatomy of a Gunboat War. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press. ISBN 9781572492165. OCLC 606812824.

- Malanowski, Jamie (2014). Commander Will Cushing : daredevil hero of the Civil War. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393245790. OCLC 902661366.

- McQuiston, J. R. (2013). William B. Cushing in the Far East. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 9780786470556.

- Roske, Ralph; Van Doren, Charles (1995). Lincoln's Commando: The Biography of Commander W. B. Cushing, USN (Revised and Expanded ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781557507372.

- Schneller, R. J. (2004). Cushing: Civil War SEAL. Sterling: Potomac Books. ISBN 9781574885064.

- Stempel, J. (2011). The CSS Albemarle and William Cushing. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 9780786488735.

External links

- "Cushing, William Barker". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- "Cushing, William Barker". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 667.