William Bradbury (printer)

William Bradbury (13 April 1799 – 11 April 1869) was an English printer and publisher. He is known for his work as a partner from 1830 in Bradbury and Evans, who printed the works of a number of major novelists such as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, as well as leading periodicals such as Punch, which they also owned.[1]

Early life

Bradbury was born in Bakewell in Derbyshire, where he was baptized on 14 April 1799.[2] He was the son of John Bradbury (1776–1834), a shoemaker, and his wife, Elizabeth née Hardwick (1775-1820). By 1811 the family had moved to Lincoln[3] where Bradbury was expected to follow his father into shoemaking. Instead, in 1813 he entered into a seven-year apprenticeship as a compositor under John Drury (1757-1815) and after his death his son John Wold Drury (1789-1850).[4] By 1821 Bradbury had set up his own printing firm on Castle Hill in Lincoln. From 1822 to 1830 he went into business with his soon-to-be brother-in-law William Dent (1792-1858), who married Bradbury's sister Mary in June 1825. On 6 July 1826 Bradbury married Sarah Price (c1803-1896) in his native Bakewell. The couple had five children: Letitia Jane Bradbury (1827-1839); the writer Henry Riley Bradbury (1831-1860), who killed himself by drinking acid, possibly on being refused in marriage by a daughter of Frederick Mullett Evans, his father's partner, or perhaps as a result of being accused of plagiarism by Alois Auer;[5] William Hardwick Bradbury (1832-1892), who in 1865 was to take over the business on his father's retirement; Walter Bradbury (1840-1891); and Edith Bradbury (1842-1910).[4][6]

Move to London

In 1824 Bradbury and Dent published their first book, The Poll for the Election of a Knight of the Shire for the County of Lincoln, taken November 26 to December 6, 1823, following which they relocated to London, where they set up their printing business at 76 Fleet Street,[7] During one of the firm's several moves they gained another partner, Samuel Manning, and became Bradbury, Dent, and Manning. In 1830 that partnership was dissolved and Bradbury entered into a new one with the printer Frederick Mullett Evans (1803-1870). Bradbury's long experience in all aspects of printing and his ability to personally oversee the most difficult of jobs earned Evan's respect, he later commenting on "Bradbury's excellent taste as a printer and his influence in raising the quality of printing in England."[6]

Bradbury and Evans

.png.webp)

In July 1833 Bradbury and Evans installed a newly designed large, steam-driven cylinder printing press which they kept running twenty-four hours a day six days a week.[6] For the first ten years of the firm's existence Bradbury and Evans were printers, but they added publishing in 1841 after they acquired the satirical magazine Punch.[8][9][10] Bradbury and Evans began the tradition of holding a weekly dinner for the contributors to Punch which Bradbury regularly attended in the early years, and the magazine's staff became the nucleus of the owners' social circle.[6] A keen gardener, in 1841 he co-founded perhaps the most famous horticultural periodical, The Gardeners' Chronicle along with John Lindley, Charles Wentworth Dilke and Joseph Paxton.

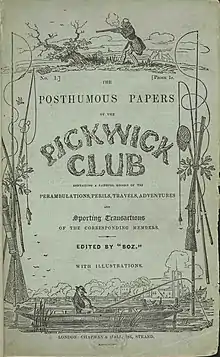

Because Bradbury and Evans kept their presses running through day and night they often took on large jobs for other printers and publishers with tight deadlines, sometimes printing The London Journal and even The Illustrated London News on one occasion.[6] They printed Paxton's Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants for Joseph Paxton,[11] as well as printing for the publisher and bookseller Edward Moxon[10] and Chapman & Hall (publishers of Charles Dickens), for whom Bradbury and Evans printed the serial novels The Pickwick Papers (1836-7) and Nicholas Nickleby (1838-9).[9]

Charles Dickens and others

When Bradbury's daughter Letitia Jane died in 1839 aged 11[12][13] Dickens wrote to him offering his 'earnest and sincere sympathy and warm regard', saying that he knew what Bradbury was going through as he himself had lost 'a young and lovely creature' in the person of his sister-in-law Mary Hogarth, almost two years before.[14][15][16] Dickens, his wife Catherine, and her sister Georgina Hogarth became fond of Bradbury and his wife Sarah over the coming years, with Dickens nicknaming Bradbury 'Beau B' while lampooning his Derbyshire accent, while Georgina Hogarth was able to imitation Mrs Bradbury with great accuracy. When on 20 December 1855 the Bradburys held a party at which Dickens, John Forster, and the Punch staff were present they were treated to 'the very best cooked dinner' Dickens had 'ever sat down to' in his life. In a letter to his wife Catherine Dickens he wrote that after the party Mrs Bradbury told him of the occasion when her husband burned down their bed while she was away and secretly replaced it. When she returned home and laid her 'luxuriant and gorgeous figure' between the sheets she sat up sharply and exclaimed, 'William, where his me bed? - This is not me bed - wot has 'append William? -Wot ave you dun with me bed?’[17]

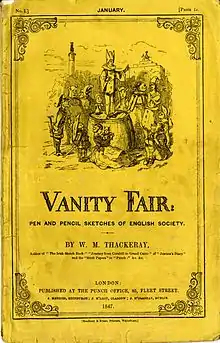

When Dickens left Chapman and Hall in 1844 Bradbury and Evans became his new publisher.[9] From 1844 to 1859 they printed and published all of Dickens's new works, leading to great profits for both sides and the enhancement of Dickens's reputation.[6] In 1847 they published William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair (as a serial), in addition to most of his longer fiction.[9][10] The firm operated from offices at no.11 Bouverie Street, no.85 Fleet Street, and no.4-14 Lombard Street, London (now Lombard Lane).[18][19]

The inclusion of a monthly supplement, Household Narrative, in the weekly Household Words edited by Dickens was the occasion for a test case on newspaper taxation in 1851. Bradbury and Evans as publishers might have found themselves in the forefront of the ongoing campaign against "taxes on knowledge"; but the initial court decision went in their favour. The government then tried amending the existing law, to duck public opinion, reversing the stand taken by the revenue on the definition of "newspaper".[20][21]

Later years

.jpg.webp)

Bradbury and Evans parted company with Dickens in 1859 when they refused to carry an advertisement by Dickens in Punch explaining why he had separated from his wife, Catherine Dickens.[9] Furious at their refusal, Dickens immediately cut all business and personal connections with them, returning to his old publisher, Chapman and Hall. When Bradbury and Evans learned of what Dickens had done they were shocked, later writing:

"... it did not occur to Bradbury and Evans to exceed their legitimate functions as proprietors and publishers, and to require the insertion of statements on a domestic and painful subject in the inappropriate columns of a comic miscellany ."[22]

As a result, they founded the illustrated literary magazine Once a Week, in direct competition with Dickens' new All The Year Round (the successor to Household Words).[9] Leading illustrators of the time contributed to the firm's publications, including Hablot Knight Browne (‘Phiz’), John Leech[23] and John Tenniel.

During the early 1860s Bradbury began to feel the effects of protracted periods of illness. In addition, he never got over the shock of his son Henry's distressing suicide in 1860. In the summer of 1865 Bradbury attended the weekly Punch dinner for the first time in three years where all present were pleased to see him. He spoke of his gratitude at the recent improvement in his health, adding he had thought he would never be well enough to join his "dear old friends again."[4][24] In November 1865 William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans finally retired and dissolved their 35-year partnership.[4][25]

The founders' sons, William Hardwick Bradbury (1832–1892) and Frederick Moule Evans (1832–1902), continued the business on the retirement of their fathers,[26] with the much needed financial backing of William Agnew and his brother Thomas,[27][28] Bradbury's son William Hardwick Bradbury and his daughter Edith having married into the Agnew family. The firm then became Bradbury, Evans & Co.[6]

William Bradbury died from a protracted bout of bronchitis at his family home, 13 Upper Woburn Place, Tavistock Square, London, two days short of his 70th birthday.[29] He was buried with his son Henry Bradbury in Highgate Cemetery.[4] The South London Chronicle recorded that:

"On the 15th inst., the mortal remains of Mr. W. Bradbury, the well-known printer and publisher, were interred at Highgate Cemetery. Amongst the mourners were his son, Mr. Wm. Bradbury; his partner, Mr. F. M. Evans, Mr. Mark Lemon, and several relatives, friends and workmen."[30]

References

- Paul Schlicke (3 November 2011). The Oxford Companion to Charles Dickens: Anniversary Edition. OUP Oxford. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-964018-8.

- Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Derbyshire Church of England Parish Registers; Diocese: Diocese of Derby; Reference Number: D 2057 A/PI 29

- see Lincoln St Mary Magdalene Parish Records - Marriages & Banns (1811-1812). John Bradbury was a witness to the marriage of William Dobson and Ann Waits 22 July 1811

- Chadwick, Jane. William Badbury, An Inky Tale website

- 'Plant, Exploring the Botanical World' (Phaidon Press, 2016)

- Robert L. Patten and Patrick Leary. Bradbury, William (1800–1869), printer, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2003

- A Directory of Printers and Others in Allied Trades London and Vicinity 1800-1840, (1972) Willliam B. Todd page 23

- Bradbury and Evans (London), Royal Academy of Arts Collection

- John Sutherland (1989). "Bradbury and Evans". Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction.

- Bradbury and Evans at Victorian Web, last accessed January 2011.

- Paxton, Sir Joseph. Paxton's Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants. London Bradbury & Evans for Orr and Smith and W. S. Orr and Co, 1834-1849.

- London Metropolitan Archives, Saint Mary, Stoke Newington, Register of burials, 1813 Jan-1851 Dec, P94/MRY/037; Call Number: P94/MRY/037

- England & Wales, FreeBMD 1837-1915 Death Index: Name Letitia Jane Bradbury; Registration Year 1839; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Hackney; Inferred County London; Volume 3; Page 118

- Forster, John (13 March 1839). "Condolences". Letter to Bradbury, William. Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University.

- Sawyer, C. J., Dickens v. Barabbas (1930), p 61

- Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. M. House, G. Storey, and others, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 12 vols. (1965-2002), 1.515-16 and n.

- Letters of Charles Dickens, 7.769-70

- Post Office London Directory. 1852. p. 628 – via University of Leicester, Library.

- John Timbs (1867), "Whitefriars", Curiosities of London (2nd ed.), London: J.C. Hotten, OCLC 12878129

- Martin Hewitt (5 December 2013). The Dawn of the Cheap Press in Victorian Britain: The End of the 'Taxes on Knowledge', 1849-1869. A&C Black. pp. 62–3. ISBN 978-1-4725-1456-1.

- The Law Journal for the Year 1832-1949: Comprising Reports of Cases in the Courts of Chancery, King's Bench, Common Pleas, Exchequer of Pleas, and Exchequer of Chamber. E. B. Ince. 1852. pp. 12–24.

- Once a Week Mr Charles Dickens and His Late Publishers Volume 1, Number 1 July 2, 1859

- "Exhibition of Pictures by Mr. John Leech", Saturday Review, 24 May 1962,

Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly

- Silver, Henry. Diary entry, 21 June 1865. Punch Archive. British Library

- The London Gazette, 14 November 1865

- Patten, Robert L. (23 September 2004). "Bradbury, William Hardwick (1832–1892), publisher". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56409. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Laurel Brake; Marysa Demoor (2009). "F.M. Evans". Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. Academia Press. ISBN 978-90-382-1340-8.

- Frederic Boase (1908). Modern English Biography. Netherton and Worth.

- England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name William Bradbury; Estimated Birth Year abt 1800; Registration Year 1869; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Pancras; Inferred County London; Volume 1b; Page 19

- South London Chronicle, 24 April 1869