William Crowe (poet)

William Crowe (1745–1829) was an English poet, the son of a carpenter and educated as a foundationer at Winchester College. He went to Oxford, where he became public orator.

William Crowe | |

|---|---|

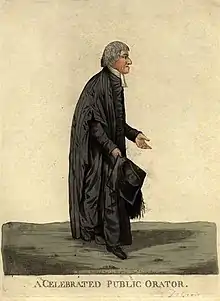

William Crowe, 1808 caricature by Robert Dighton | |

| Born | 1745 Midgham, Berkshire |

| Died | 9 February 1829 Queen Square (Bath) |

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford |

| Genre | Poetry |

Crowe was a clergyman and rector of Alton Barnes in Wiltshire. He wrote a popular, but somewhat conventional poem, Lewesdon Hill in 1789, edited William Collins's Poems in 1828, and lectured on poetry at the Royal Institution. His poems were collected in 1804 and 1827.[1]

Life

William Crowe was born at Midgham, Berkshire, and baptised 13 October 1745. His father, a carpenter by trade, lived during Crowe's childhood at Winchester, where the boy occasionally sang as a chorister in Winchester College chapel. At the election in 1758, he was placed on the roll for admission as a scholar at the college, and was duly elected a "poor scholar". He was fifth on the roll for New College, Oxford at the election in 1764, and succeeded to a vacancy on 11 August 1765. After two years of probation he was admitted as Fellow in 1767, and became a tutor of his college. On 10 October 1773, he took the degree of B.C.L.[1]

Crowe continued to hold his fellowship until November 1783, although, according to Thomas Moore, he had several years previously married "a fruitwoman's daughter at Oxford" and had become the father of several children. In 1782, on the presentation of his college, he was admitted to the rectory of Stoke Abbott in Dorset, which he exchanged for Alton Barnes in Wiltshire in 1787, and on 2 April 1784 he was elected the public orator of Oxford University. Crowe retained this position and the rectory of Alton Barnes until his death in 1829, and he discharged his duties as orator until he was advanced in years.[1]

According to the Clerical Guide, Crowe was also rector until his death at Llanymynech in Denbighshire, from 1805, and incumbent of Saxton in Yorkshire, valued at about £80 a year, from the same date. A portrait of Crowe is preserved in New College library. A grace for the degree of D.C.L. was passed by his college on 30 March 1780, but he does not seem to have proceeded to take it.[1]

Crowe and Samuel Rogers were close friends. After a short illness, he died at Queen Square, Bath on 9 February 1829, aged 83.[1]

Reputation

Anecdotes were told of his eccentric speech and his rustic manners. In politics he was an extreme Whig, close to being a republican, and he sympathised with the early stages of the French Revolution. He was accustomed to walk from his living in Wiltshire to his college at Oxford. His appearances in the pulpit or in the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford were always welcomed by the graduates of the university; his Latin sermons at St. Mary's or his orations at commemoration, graced as they were by a fine rich voice, enjoyed great popularity.[1]

Crowe was interested in architecture, and occasionally read a course of lectures on that subject in New College hall. The merits of his lectures at the Royal Institution on poetry were praised by Thomas Frognall Dibdin. When he visited Horne Tooke at Wimbledon, a considerable portion of his time was spent in the garden. He was skilled in valuing timber, from associating with farmers. His portrait as "a celebrated public orator" was drawn by Robert Dighton January 1808 in full-length academicals and with a college cap in his hand.[1]

Works

Lewesdon Hill is Crowe's poem on the hill in the western part of Dorset, on the edge of the parish of Broadwindsor, of which Tom Fuller was rector, and near Crowe's benefice of Stoke Abbott. The poet is depicted as climbing the hill-top on a May morning and describing the prospect, with its associations, which his eye surveys. The first edition, issued anonymously and dedicated to Jonathan Shipley, was published at the Clarendon Press, Oxford, in 1788. A second impression, with its authorship avowed, was demanded in the same year, and later editions, in a much enlarged form, and with several other poems, were published in 1804 and 1827.[1]

Crowe's other works were:

- ‘A Sermon before the University of Oxford at St. Mary's, 5 Nov. 1781.’

- ‘On the late Attempt on her Majesty's Person, a sermon before the University of Oxford at St. Mary's, 1786.’

- ‘Oratio ex Instituto ... Dom. Crew.’ 1788. From the preface it appears that the oration was printed in refutation of certain slanders as to its character which had been circulated. It contained his views on the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

- ‘Oratio Crewiana,’ 1800. On poetry and the poetry professorship at Oxford.

- ‘Hamlet and As you like it, a specimen of a new edition of Shakespeare’; anonymous by Thomas Caldecott and Crowe, 1819, with later editions in 1820 and 1832. The two authors contemplated a new edition of Shakespeare. Caldecott was Crowe's schoolfellow at Winchester and lifelong friend.

- ‘A Treatise on English Versification,’ 1827, dedicated to Caldecott.

- ‘Poems of William Collins, with notes, and Dr. Johnson's Life, corrected and enlarged,’ Bath, 1828.

Crowe's son died in battle in 1815, and in Notes and Queries [2] there is a Latin monody by his father on his loss. His verses intended to have been spoken at the theatre at Oxford on the installation of the Duke of Portland as chancellor were praised by Rogers and Moore. His sonnet to Petrarch is included in the collections of English sonnets by Robert Fletcher Housman and Alexander Dyce. [1]

Crowe contributed articles to Rees's Cyclopædia, but the topics are not known.

External links

![]() Media related to William Crowe (1745–1829) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Crowe (1745–1829) at Wikimedia Commons

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Courtney, William Prideaux (1888). "Crowe, William (1745-1829)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 239–240.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Courtney, William Prideaux (1888). "Crowe, William (1745-1829)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 239–240.  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.