William Molyneux

William Molyneux FRS (/ˈmɒlɪnjuː/; 17 April 1656 – 11 October 1698) was an Anglo-Irish writer on science, politics and natural philosophy.

William Molyneux | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 April 1656 |

| Died | 11 October 1698 (aged 42) Dublin, Ireland |

| Resting place | St. Audoen's Church, Dublin (Church of Ireland) |

| Nationality | Anglo-Irish |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Dublin Philosophical Society |

| Spouse | Lucy Domville (1678–91; her death) |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society |

He is noted as a close friend of fellow philosopher John Locke, and for proposing Molyneux's Problem, a thought experiment widely discussed.

Life

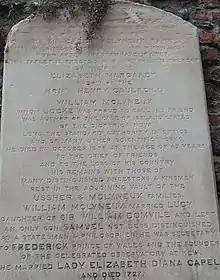

He was born in Dublin to Samuel Molyneux (1616–1693), lawyer, landowner and Master Gunner for Ireland, (whose grandfather, Sir Thomas Molyneux, had come to Dublin from Calais in the 1560s), and his wife, Anne, née Dowdall.[1] The second of five children, William Molyneux came from a relatively prosperous Anglican background, with his father established at Castle Dillon in County Armagh, and his uncle Colonel Adam Molyneux holding large estates inherited from the Dowdall's in Ballymulvey, near Ballymahon in County Longford. He was close to his brother Sir Thomas Molyneux, with whom he later shared philosophical interests. His sister Jane married Anthony Dopping, the eventual Anglican Bishop of Meath. In 1671 Molyneux started at Trinity College Dublin where he became an avid reader of the leading figures of the Scientific Revolution. After attaining a Bachelor of Arts there, Molyneux was sent to study law in the Middle Temple, London from 1675 to 1678. In 1678 he married Lucy Domville (?–1691), the youngest daughter of Sir Wiliam Domville, the Attorney-General for Ireland, and his wife Bridget Lake. His wife became ill, which led to blindness after their marriage, and died young. Of their 3 children, only Samuel Molyneux (1689–1728) lived past childhood. Samuel went on to become an astronomer and politician who worked with his father on various scientific endeavours.[2]

Career and publications

Because of his inheritance, Molyneux was financially independent.[3] Nonetheless, he held a number of official positions throughout his life. He was appointed Joint Surveyor General of the King's buildings and works in Ireland in 1684, serving alongside William Robinson. In 1687 he invented a new type of sundial called a Sciothericum telescopicum that used a special double gnomon and a telescope to measure the time of noon to within 15 seconds.[4] He represented Dublin University in Parliament from 1692 until his death. He had also served as a commissioner of forfeited estates in 1693, resigning a few months later due to ill health.

Meanwhile, Molyneux was responsible for a number of publications reflecting his diverse interests. His first book was editing and translating into English the work of René Descartes which was published in London, 1680 as Six Metaphysical Meditations, Wherein it is Proved that there is a God.... In 1682 Molyneux collaborated with Roderic O'Flaherty to collect material for Moses Pitt's Atlas. In 1685, Pitt's financial crisis lead to cancellation of the project but much valuable early Irish history had been collected. Molyneux struck a friendship with O'Flaherty and assisted when the latter's treatise Ogygia was published in London.[5]

Meanwhile, in October 1683 he founded the Dublin Philosophical Society along the lines of the Royal Society (of which Molyneux became a fellow in 1685), and became its first Secretary.[6] He was active in the proceedings of the society—recording weather data, calculating eclipses and demonstrating instruments and experiments.[5]

Molyneux also published several papers in Philosophical Transactions, as well as papers on optics, natural philosophy, and miscellaneous topics.[7] Perhaps his best known scientific work was Dioptrica Nova, A treatise of dioptricks in two parts, wherein the various effects and appearances of spherick glasses, both convex and concave, single and combined, in telescopes and microscopes, together with their usefulness in many concerns of humane life, are explained, published in London 1692.[7]

After John Locke published his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Molyneux wrote to him praising the work.

Early in 1698, Molyneux published The Case of Ireland's being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated. This controversial[5] work—through application of historical and legal precedent—dealt with contentious constitutional issues that had emerged in the latter years of the seventeenth century as a result of attempts on the part of the English Parliament to pass laws that would suppress the Irish woollen trade. It also dealt with the disputed appellate jurisdiction of the Irish House of Lords. Molyneux's arguments reflected those made in an unpublished piece written about 1660 by his father-in-law Sir William Domville, entitled A Disquisition Touching That Great Question Whether an Act of Parliament Made in England Shall Bind the Kingdom and People of Ireland Without Their Allowance and Acceptance of Such Act in the Kingdom of Ireland.[8]

Following a debate in the English House of Commons, it was resolved that Molyneux's publication was 'of dangerous consequence to the crown and people of England by denying the authority of the king and parliament of England to bind the kingdom and people of Ireland'.[9] Despite condemnation in England, Molyneux was not punished but his work was condemned as seditious and was ceremonially burned at Tyburn by the public hangman. His arguments remained topical in Ireland as constitutional issues arose throughout the eighteenth century, and formed part of Swift's argument in Drapier's Letters.[10] The tract also gained attention in the American colonies as they moved towards independence. Although The Case of Ireland, Stated was later associated with independence movements—both in Ireland and America—as one historian points out, 'Molyneux's constitutional arguments can easily be misinterpreted' and he was 'in no sense a separatist'.[11]

Legacy

Molyneux also proposed the philosophical question that has since become known as Molyneux's Problem, which Locke discussed in later editions of the Essay. The problem of the blind man who gains sight, which he proposed to Locke, is a topic that has been discussed extensively since its publication and into the 21st Century.[12][13] The University Philosophical Society of Trinity College Dublin views itself as the successor of the Dublin Philosophical Society, and thus recognises Molyneux as its founder and first president. Molyneux died in Dublin on 11 October 1698 and was buried in St. Audoen's Church, within the burial vault of his great-grandfather, Sir William Ussher.

References

- Dublin Historical Record, 1960

- Science and Its Times via William Molyneux Summary. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- James G. O'Hara, 'Molyneux, William (1656–1698)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 4 November 2008

- "Philosophical Transactions, Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious, in Many Considerable Parts of the World". C. Davis, Printer to the Royal Society of London. 20 November 1688. Retrieved 20 November 2019 – via Google Books.

- James G. O'Hara, 'Molyneux, William (1656–1698)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008

- Hoppen, K. Theodore (1963). "The Royal Society and Ireland. William Molyneux, F.R.S. (1656–1698)". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 18 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1963.0016. JSTOR 531268. S2CID 144682057.

- "The Galileo Project". galileo.rice.edu. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Patrick Kelly. 'Sir William Domville, A Disquisition Touching That Great Question...', Analecta Hibernica, no. 40 (2007): 19–69.

- James G. O'Hara, 'Molyneux, William (1656–1698)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 29 Feb 2008

- Ferguson, Oliver W. Jonathan Swift and Ireland p. 119

- David Dickson, New Foundations: Ireland 1660–1800 (Dublin, 2000), 50.

- Degenaar, Marjolein (1996). Molyneux's Problem: Three Centuries of Discussion on the Perception of Forms. International Archives of the History of Ideas / Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Idées. Vol. 147. Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-0-585-28424-8. ISBN 978-0-585-28424-8.

- Gareth Evans (2002). "Molyneux's Question". In Alva Noë; Evan Thompson (eds.). Vision and Mind: Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception. MIT Press. ISBN 0262640473.

Works

External links

![]() Media related to William Molyneux at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Molyneux at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by William Molyneux at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Europa Biography

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "William Molyneux", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- From The Online Library of Liberty: The Case of Ireland being bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated [1698]

- Molyneux's (1692) Dioptrica nova; A treatise of dioptricks in two parts - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- Plaque #55087 on Open Plaques