William Peter Hamilton

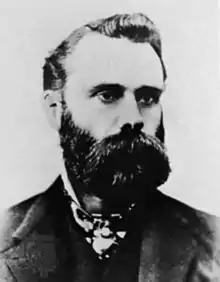

William Peter Hamilton (January 20, 1867 – December 9, 1929), a proponent of Dow Theory, was the fourth editor of the Wall Street Journal, serving in that capacity for more than 20 years (i.e., January 1, 1908 – December 9, 1929).[1][2][3]

- "Some people think and others do. Dow thought and created an index and pondered it. Hamilton [by contrast,] put it to practice as a workhorse. He was the first serious practitioner of [both] the art of forecasting future stock action based on precise prior action [and the] forecasting of the economy based on the market."[4]

William Peter Hamilton | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) William Peter Hamilton c.1910-1913 | |

| Born | January 20, 1867 |

| Died | December 9, 1929 (aged 62) Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Author, Journalist, Editor, Technical Analyst |

| Years active | 1890–1929 |

| Spouse(s) | Georgianna Tooker (1850-1916) (m. 1901; died 1916) Lillian Hart (1861-1955) (m. 1917) |

Family

Of Scottish heritage, and the son of Thomas Hamilton (born 1835), and Jane Elizabeth (née Earnshaw) Hamilton (born 1845), William Peter Hamilton was born in Manchester, England on January 20, 1867.[5]

He married Georgiana Tooker in 1901.[6] He married his second wife, Lillian Hart, in New York, on 19 May 1917.

Journalist

Having earlier worked as a clerk on the London Stock Exchange,[7] he began his career in journalism in London, in 1890, with The Pall Mall Gazette, under the editorship of William Thomas Stead (1849-1912).

In 1893 and 1894, he served in Africa as a Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers of the British Auxiliary Forces during the First Matabele War, and also as a corporal in the British Bechuanaland Police.[8][1] He also served as a war correspondent for the Gazette during that time; and, once the war was over, he remained in Johannesburg, working as a financial journalist.[9]

The Wall Street Journal

First issue (July 8, 1889).

Having moved from South Africa to Australia, "where he represented London newspapers" (Hogate, 1929), he migrated to New York, and joined the staff of the Wall Street Journal in 1899.

On January 1, 1908, when Sereno S. Pratt, who had been WSJ's editor since late 1905, and the author of The Work of Wall Street (1906), replaced George Wilson (1868-1908) as the secretary of the New York Chamber of Commerce, Hamilton was promoted — directly at the behest of Barron's wife, Jessie Maria Barron (1852-1918), née Barteau, née Waldron[10] — to the position of editor of the Wall Street Journal, where he eventually became a strong advocate of Dow Theory (see: "The six basic tenets of Dow Theory).[11]

- "After (Charles Henry) Dow's death in 1902 there followed in quick succession two editors of The Wall Street Journal who were not interested in Dow's theories of market action.[12] Only a year after Dow's death, William Peter Hamilton, who had served as a reporter under Dow from 1899 to 1902, became an editorial writer and, in January, 1908, became editor. While this gives continuity, it should not be thought that Hamilton was an avid disciple of Dow's. In the period 1903 to 1918, he mentioned the Dow theory in four editorials. It was not until he became interested in publishing a book of his own in 1922 that Hamilton began frequent reference to Dow's theory. He mentioned Dow's theory in four out of eight articles in 1921 and seven out of eleven articles in 1922. In the seven years following, he mentioned the theory in eleven out of forty-three editorials." — Woodward, (1968), p.14.

- "Hamilton had an uncannay [sic] knowledge of market fluctuations [and, from this,] much of the authority gained by the [Dow] indices [is directly due to Hamilton's efforts] since he chose to utilise them in enunciating his own generalisations, which were really grounded on an extremely sound knowledge of the market". — Torliev Hytten, The Sydney Morning Herald, August 2, 1938.[13][14]

- "William Hamilton, late editor of the "Wall-street Journal", who wrote many leading articles on the theory first invented by Charles H. Dow, likened the movement of the averages to that of the sea; the tide, gradually coming in or going out, he compared with the primary or year-to-year market trend; the waves he represented as being the intermittent changes. In these broad movements which he called the secondary, or month-to-month trends; and he looked upon the ripples as being the day-to-day changes which are only important because they eventually form the secondary trend." — The West Australian, September 28, 1937.[15]

- "William Peter Hamilton . . . had an extraordinary flair for predicting market trends, apart from any scientific method of deduction as the result of studying Dow Jones averages. It is of interest that a few weeks before his death in November 1929 Hamilton correctly called attention to the beginning of the great bear market that was destined to run for nearly five years." — The (Melbourne) Argus, October 18, 1937.[16][17]

Barron's National Financial Weekly

In addition to his regular editorials in the WSJ, Hamilton contributed a wide range of articles on financial and economic topics, from time to time, to Barron's National Financial Weekly, a weekly financial newspaper owned by Clarence W. Barron (1855-1928), who also owned the WSJ.

Apart from twenty-or-so excerpts from his forthcoming The Stockmarket Barometer published sequentially between 1921 and 1922, his Barron's contributions included:

- Cycles, And Stock Market Averages, June 6, 1921.

- Like the Dyer's Hand, November 6, 1922.

- An Investment in Education: An Excellent Opportunity for a Rich Benefactor, November 27, 1922.

- The Stock Market Barometer: A Policy of Insurance, December 4, 1922.

- A Stockholder's Plea for Courage, January 15, 1923.

- British Politics and Finance, May 28, 1923.

- A Further Plea for Courage, June 4, 1923.

- How Britain Comes Back, June 4, 1923.

- Britain's Credit Structure, June 11, 1923.

- English and American Financing, June 18, 1923.

- The British Rubber "Monopoly": Not a Menace — Reasons for Giving American Financial Backing, July 2, 1923.

- British Railways in American Eyes: Consolidation's Prospects, Parallels and Limitations, July 16, 1923.

- The Betting Evil in Great Britain, July 23, 1923.

- Government Ownership and Operation: A World-Wide Delusion and Its Failure Under Test, December 17, 1923.

- Observations in the Southwest: Business Men Hopeful of Outlook, but Sick of Politics, March 31, 1924.

- A Study of Kansas City Southern: An Inspection Trip of This Well Managed Road Reveals Interesting Things, April 7, 1924.

- Charles G. Dawes — A Personal Study, June 23, 1924.

- Stock Exchange Settlements: London and New York Methods Compared, July 28, 1924.

- The Stock Market Barometer 1922—1925, February 9, 1925.

- When Virtue has Its own Reward, June 5, 1925.

- Railroads and the East Wind: Change of Policy Needed — A Suggested Representative for All the Railroads, November 16, 1925.

- Washington Impressions: Early Adjournment of Congress Likely — The Woodlock Case, April 19, 1926.

- The British Coal Strike and the Soviet: Leader of Miners Openly Allied with Extremists of Moscow — Certain to Lose, June 28, 1926.

- The Flight from the Franc: Situation Worries French Bankers, July 12, 1926.

- A Misplaced Magnanimity, July 12, 1926.

- The Stock Market Barometer, August 9, 1926.

- A New Condition, March 25, 1929.

- Call Money and Stocks: A Practicable Stock Exchange Reform, April 8, 1929.

Editorial style

_-(1922).jpg.webp)

He was renowned for the concise precision of his editorials. In his obituary, the journalist, newspaper publisher, and financial editor of The New York Times from 1896 to 1906, Henry Alloway (1856-1939) spoke of "the logic, force and pungency of [Hamilton's] Wall Street Journal editorial declarations" (Alloway, 1929).

For instance, in Hamilton's WSJ obituary it was noted that:

- "Mr. Hamilton's editorials were widely read and there is abundant evidence that time and again they exerted a positive and practical influence. Their appeal to thinking men and women may perhaps be attributed in large part to the facility with which he brushed non-essentials aside and went straight to the heart of the question. This power accounted also for his mastery of condensation; he could say so much in so little space. But this was no mere trick of the pen — it was part of his innate character to think with directness and to speak with candor, wasting no time upon trivial compromises with passing modes of thought. His unusual intellectual vigor, moreover, was suffused by a delicate appreciative humor which frequently gave unexpected and delightful turns to his spoken and written thought." — The Wall Street Journal, December 10, 1929.[18]

In his extended 1922 Editor & Publisher interview, Hamilton directly addressed what he felt was the significant difference between a "real editorial" and others that were "merely lengthy dissertations":[19]

- "Of the 22,000 editorials which I estimate the newspapers of the country print each week, 21,500 might far better never have been printed. . . . .

I believe that an editorial should leave the reader with a single thought in his mind and not a multiplicity of unrelated ideas. The true editorial might well be constructed as a simple syllogism — with a major premise founded upon a truth, a minor premise based upon the news of the day, and a conclusion, which is the logical deduction.

You can put your premises, illustrations and conclusions in any way you please, but you must arrest the reader’s attention before the end of the first line. The title can often serve this purpose. This can all be done in not more than 450 words. An editorial needs a mighty good excuse to be longer.

The long editorials that you see too frequently tire the reader before he is half through and, what is more serious, they leave him with a confusion of images and opinions instead of a clearly crystallized thought not the truth implicit in the day’s news.

Why is it that such an overwhelming proportion of the editorials printed throughout the country do not qualify? When you suggest lack of disciplined thought you have gone, I think, to the root of the trouble.

You can’t write a fifty-fifty editorial. Don’t believe the man who tells you that there are two sides to every question. There is only one side to the truth." — Editor & Publisher, September 2, 1922.

- "Of the 22,000 editorials which I estimate the newspapers of the country print each week, 21,500 might far better never have been printed. . . . .

Death

He died at his Brooklyn, New York home of pneumonia on December 9, 1929.[20] His funeral services were conducted at Grace Church, in Brooklyn, on Thursday, December 12, 1929.[21]

Works

- 1922: The Stock Market Barometer.

- 1928: The Stock Market Barometer (Revised Edition).

Notes

- NYT.1.

- Brown, Goetzmann & Kumar, Alok (1998).

- Note that this "William P. Hamilton" is a completely different individual from the "William P. Hamilton" — William Pierson Hamilton (1869–1950) — a banker, who married Juliet Pierpont Morgan (1870-1952), the daughter of John Pierpont Morgan (1869–1950) on April 12, 1894.

- Fisher (2007), p. 262.

- WWA.1.

- NTR.1.

- Bishop (1961), p.25.

- The Roll of Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Men of the British South Africa Company Forces and of the Imperial Troops who were awarded the Medal for Operations in Matabeleland, Rhodesia, 1893, published c.1896 by the British South Africa Company shows (at page 10) that Corporal William Hamilton, service number 2178, of the British Bechuanaland Police was awarded the Medal for Matabeleland 1893. (For details of the Medal awarded to Hamilton, see: Irwin (1910), Plate XV (facing p.136); and pp.137-138.)

- Fisher (2007), p.261.

- Melloan (2017), p.11.

- Rhea (1932) has an appendix containing 252 of Hamilton’s editorials on “the averages”.

- Namely, Thomas Francis Woodlock (1866-1945) and Sereno Stansbury Pratt (1858-1915).

- Hytten (1938).

- For more on the eminent Swedish/Australian economist Torliev Hytten (1890-1980) see Davis (1996).

- TWA.1..

- TMA.1.

- Hamilton's most famous WSJ editorial, "A Turn in the Tide", within which he declared that the "bull market" was over, was published on Friday, October 25, 1929 — the morning after "Black Thursday" (October 24), wherein the market had lost 11% of its opening value on very heavy trading.

- WSJ.2.

- Ormsbee (1922), p.5.

- Hogate (1929).

- WSJ.3.

References

- Alloway, Henry (1929), "Stalwart, Philosopher, Friend", The Wall Street Journal, (Saturday, December 14, 1929), p. 3

- Bishop, George W., Jr. (1960), Charles H. Dow and the Dow Theory, New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Bishop, George W., Jr. (1961), "Evolution of the Dow Theory", Financial Analysts Journal, Vol.17, No.5, (September–October 1961), pp. 23–26; JSTOR 4469247

- Brown, Stephen J., Goetzmann, William N. & and Kumar, Alok (1998), "The Dow Theory: William Peter Hamilton's Track Record Reconsidered", The Journal of Finance, Vol. 53, No.4, pp. 1311–1333; JSTOR 117403

- Button, H.C. (1923), An Investigation to Determine the Dependability of Dow's Theory of Interpreting the Stock Market Averages, as Exemplified by WP Hamilton, Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Business and Engineering Administration.

- Davis, R.P. (1996), "Hytten, Torleiv (1890-1980)", p. 531 in Ritchie, J. (ed.)Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol.14: 1940—1980: Di-Kel, Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

- Fisher, Kenneth L. (2007), "William P. Hamilton: The First Practitioner of Technical Analysis", pp. 260–262 in Fisher, Kenneth L., 100 Minds that Made the Market, Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons; ISBN 978-0-470-13951-6

- Hamilton, William Peter (1910), "The Case for the Newspapers", The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 105, No. 5 (May 1910), pp. 646-654

- Hamilton, William Peter (1915), "Fictitious Values cannot be Maintained on New York Stock Exchange", The (Moscow, Idaho) Daily Star-Mirror, (Tuesday, July 27, 1915), p. 2

- Hamilton, William Peter (1922), The Stock Market Barometer: A Study of its Forecast Value based on Charles H. Dow's Theory of the Price Movement, with an Analysis of the Market and Its History Since 1897, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers

- Hamilton, William Peter (1925), "Are Forced Railroad Mergers Wise? — A Wall Street View", Railway Age, Vol.79, No.20. (November 14, 1925), pp. 891-893: Hamilton's address to the Railway Business Association's Dinner on November 11, 1925.

- Hamilton, William Peter (1922), "A Turn in the Tide", The Wall Street Journal, (Friday, October 25, 1929), p. 1

- Hamilton, William Peter (1928), The Stock Market Barometer: A Study of its Forecast Value based on Charles H. Dow's Theory of the Price Movement, with an Analysis of the Market and Its History Since 1897 (Revised Edition), New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Hamilton, William Peter (Pyka, Petra trans.) (1999), Der ultimative Börsen-Kompass: "The Stock Market Barometer", Rosenheim: Tm Boersenverlag AG; ISBN 978-0-470-06153-4

- Hogate, Kenneth C. (1929), "W.P. Hamilton Dies Suddenly: 40-Year Newspaper Career on Three Continents—Editor The Wall Street Journal: With Dow-Jones 30 Years", The Wall Street Journal, (Friday, December 13, 1929), pp. 1, 20

- Hytten, T. (1938), "Dow Jones Indices: Review of Theory", The Sydney Morning Herald, (Tuesday, August 2, 1938), p. 8

- Irwin, D. Hastings (1910), War Medals and Decorations Issued to the British Military and Naval Forces and Allies 1588 to 1910 (Fourth Edition, Enlarged and Corrected), London: L. Upcott Gill.

- Melloan, George (2017), Free People, Free Markets: How the Wall Street Journal Opinion Pages Shaped America, New York: Encounter Books; ISBN 978-1-594-03931-7

- Ormsbee, Thomas H. (1922), "Two Sides to all Questions? Not for Editors: Only One Side to the Truth, Declares William Peter Hamilton, Chief of the Wall Street Journal, Who Thinks 21,500 of Nation’s 22,000 Weekly Editorials Were Better Unwritten", Editor & Publisher, Vol. 55, No. 14, (Saturday, September 2, 1922), pp. 5-6

- Pratt, Sereno S. (1906), The Work of Wall Street, New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Rhea, Robert (1932), The Dow Theory: An Explanation of its Development and an Attempt to Define its Usefulness as an Aid in Speculation, New York: Barron's.

- Stansbury, Charles B. (1938), The Dow Theory Explained: How to Use it for Profit: A Simplified Explanation of the Dow Theory based on a Study of the Observations of William Peter Hamilton, and the Writer's own Experience as a Broker, Louisville, KY: Adams Publishing Company.

- Stone, Edward C. (1929), "Editor sees Bond Sales Increasing: William P. Hamilton gives Interesting Talk before Washington Club", (Washington) Evening Star, (Friday, October 18, 1929), p. 14

- Woodward, Burton M. (1968), The Dow Theory and the Management of Investments, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida.

- JAS.1: Forecasting Security Prices, Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol.20, No.150, (June 1925), pp. 244-249; JSTOR 2277120

- NTR.1: Mrs. W. P. Hamilton, The New York Tribune, (Tuesday, October 3, 1916), p. 9

- NYT.1: W. P. Hamilton, Editor, Dies At 62. Had Been in Charge of The Wall Street Journal for Last Two Decades. Began Career In London. Correspondent for British Papers in Many Countries. Took Part in First Matabele War, New York Times (Tuesday, December 10, 1929), p. 30.

- TBB.1: The Rich and Poor, The Belding Banner, (Wednesday, April 19, 1916), p. 4

- TMA.1: Forecasting Trends of Stock Market, The Argus, (Monday, October 18, 1937), p. 8

- TWA.1: The Dow Theory, The West Australian, (Tuesday, September 28, 1937), p. 14

- WSJ.1: Hamilton Reveals Methods of a Wall Street Editor: Editorial Chief Reviews Life which Led him over the World to the Wall Street Journal, The Wall Street Journal, (Tuesday, September 12, 1922), p. 9: summary of Ormsbee (1922)

- WSJ.2: Review and Outlook: William Peter Hamilton, The Wall Street Journal, (Tuesday, December 10, 1929), p. 1

- WSJ.3: Hamilton Funeral Held: Former Associates Attend Services for Editor at Grace Church, Brooklyn, The Wall Street Journal, (Friday, December 13, 1929), p. 2

- WWA.1: "Hamilton, William Peter", p. 948, in Marquis, A.N. (ed.), Who's Who in America: Vol.15: 1928-1929, Chicago: The A. N. Marquis Company.