William S. Sadler

William Samuel Sadler (June 24, 1875 – April 26, 1969) was an American surgeon, self-trained psychiatrist, and author who helped publish The Urantia Book. The book is said to have resulted from Sadler's relationship with a man through whom he believed celestial beings spoke at night. It drew a following of people who studied its teachings.

William S. Sadler | |

|---|---|

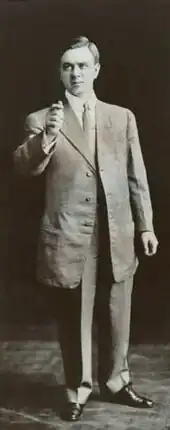

Sadler c. 1915 | |

| Born | June 24, 1875 Spencer, Indiana, US |

| Died | April 26, 1969 (aged 93) |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for | The Urantia Book |

| Spouse(s) | Lena Celestia Kellogg (1875–1939), married 1897 |

A native of Indiana, Sadler moved to Michigan as a teenager to work at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. There he met the physician and health-food promoter John Harvey Kellogg, co-inventor of corn flakes breakfast cereal, who became his mentor. Sadler married Kellogg's niece, Lena Celestia Kellogg, in 1897. He worked for several Christian organizations and attended medical school, graduating in 1906. Sadler practiced medicine in Chicago with his wife, who was also a physician. He joined several medical associations and taught at the McCormick Theological Seminary. Although he was a committed member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church for almost twenty years, he left the denomination after it disfellowshipped his wife's uncle, John Harvey Kellogg, in 1907. Sadler and his wife became speakers on the Chautauqua adult education circuit in 1907, and he became a highly paid, popular orator. He eventually wrote over 40 books on a variety of medical and spiritual topics advocating a holistic approach to health. Sadler extolled the value of prayer and religion but was skeptical of mediums, assisting debunker Howard Thurston, and embraced the scientific consensus on evolution.

In 1910, Sadler went to Europe and studied psychiatry for a year under Sigmund Freud. Sometime between 1906 and 1911, Sadler attempted to treat a patient with an unusual sleep condition. While the patient was sleeping he spoke to Sadler and claimed to be an extraterrestrial. Sadler spent years observing the sleeping man in an effort to explain the phenomenon, and eventually decided the man had no mental illness and that his words were genuine. The man's identity was never publicized, but speculation has focused on Sadler's brother-in-law, Wilfred Kellogg. Over the course of several years, Sadler and his assistants visited the man while he slept, conversing with him about spirituality, history, and cosmology, and asking him questions. A larger number of interested people met at Sadler's home to discuss the man's responses and to suggest additional questions. The man's words were eventually published in The Urantia Book, and the Urantia Foundation was created to assist Sadler in spreading the book's message. It is not known who wrote and edited the book, but several commentators have speculated that Sadler played a guiding role in its publication. Although it never became the basis of an organized religion, the book attracted followers who devoted themselves to its study, and the movement continued after Sadler's death.

Early life and education

Sadler was born June 24, 1875, in Spencer, Indiana. Of English and Irish descent, he was raised in Wabash, Indiana.[1] Samuel did not enroll his son in public schools.[2][lower-alpha 1] Despite his lack of formal education, Sadler read many books about history as a child and became a skilled public speaker at a young age.[3] Samuel was a convert to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and William was baptized into the denomination in 1888 and became devoutly religious.[4]

In 1889, William Sadler moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, to work at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, where he served as a bellhop and helped in the kitchen.[5] He also attended Battle Creek College for one year when he was 16. Both institutions had strong ties to his church and Sadler was mentored by local Adventist businessman John Harvey Kellogg,[6][lower-alpha 2] who heavily influenced Sadler's views. Sadler's early writings about health are similar to ideas advanced by John Kellogg, including the concept of autointoxication, and the idea that caffeine has negative health effects. He similarly condemned the consumption of tobacco, meat, and alcohol.[7][lower-alpha 3] Although Sadler did drink later in his life.

Sadler graduated from Battle Creek College in 1894 and subsequently worked for John Kellogg's brother, William K. Kellogg as a health-food salesman.[8][lower-alpha 4] Sadler, a skilled salesman, persuaded William Kellogg to market his products through demonstrations in retail stores.[9] In 1894, he oversaw the establishment of Life Boat Mission, a mission that Kellogg founded on State Street in Chicago.[8][lower-alpha 5] Sadler operated the mission and published Life Boat Magazine;[2][lower-alpha 6] its sales were intended to provide funds for Kellogg's Chicago Medical Mission.[10] Sadler also contributed articles to other Adventist publications, including the Review and Herald.[11] Around 1895, Sadler attended Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, Illinois, where he trained to be an evangelist, ultimately becoming an ordained minister in 1901.[12]

In 1897, Sadler married John Kellogg's niece, Lena Celestia Kellogg, a nurse whom he had met four years previously.[2] Their first child, William, called Willis, born in 1899, died a ten months later.[13] Their second child, William S. Sadler Jr., was born in 1907.[14] The couple had been interested in medicine for several years, but the loss of their child inspired them to pursue medical careers.[15] In 1901, they moved to San Francisco to attend medical school at Cooper Medical College.[13] In San Francisco, he served as the "superintendent of young people's work" for the church's California conference and the president of a local Medical Missionary society.[2] The couple also operated a home for Christian medical students.[13] In 1904, they returned to the Midwest, where they attended medical school, each earning a Doctor of Medicine degree two years later.[2][16][lower-alpha 7] Sadler was an early adopter of Freudian psychoanalysis, and believed that experiences individuals have as infants play a key role in their minds as adults, although he did not accept many of Freud's ideas about sexuality or religion.[17][18]

Although Sadler was a committed Adventist for much of his early life, he stayed less involved after John Kellogg was excommunicated in 1907 in the wake of a conflict with Ellen G. White, the church's founder.[19] The Sadlers became disenchanted with the church and subsequently criticized it.[20] Sadler rejected some Adventist teachings, such as White's status as a prophetess and the importance of Saturday as Sabbath. He retained a positive view of White and rejected allegations that she was a charlatan.[21]

Career

By 1912, Sadler and his wife, both doctors by then, operated a joint practice in Chicago that catered to children's and women's health issues.[22] Sadler initially focused on surgery, performing surgeries with his wife, but widened his practice to include psychiatric counseling in 1930[23] and became a consulting psychiatrist at Columbus Hospital.[24] As a psychiatrist, Sadler advocated an eclectic mix of techniques, applying the theories of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Adolf Meyer.[25] Sadler believed that religious faith was beneficial to mental health,[26] and specifically promoted prayer, which he believed to be most effective in the context of Christian faith.[27] However, he thought that religious beliefs were deleterious to mental health if based on fear.[26]

Sadler and his wife moved into an Art Nouveau-style house—the first steel-frame residence in Chicago—on Diversey Parkway in 1912.[28][lower-alpha 8] The couple operated their medical practice in the building.[29][lower-alpha 9] He was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and of medical associations including the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Pathological Society, and the American College of Surgeons.[24] Sadler was also a member of the faculty of McCormick Theological Seminary, and taught pastoral psychology.[30] He argued that pastors should be educated in basic psychiatry so they could recognize symptoms of mental illness in congregants.[31] His students later recalled him as an engaging and humorous public speaker.[32]

Sadler wrote about many topics.[16] In 1909, he published his first book, an evangelical work, titled Self-Winning Texts, or Bible Helps for Personal Work.[2] In the 1910s, he regularly worked all night on his writing projects.[33] In addition to 42 books, most of which were about personal health issues, he wrote magazine articles.[15][34] Many of Sadler's books focused on popular self-help topics;[35] historian Jonathan Spiro deems Sadler's The Elements of Pep a "quintessential book of the 1920s".[35] In 1936, Sadler published Theory and Practice of Psychiatry, a 1,200-page work in which he attempted to provide a comprehensive outline of psychiatry.[36]

Sadler also wrote about race:[37] he had an interest in eugenics, likely owing to Kellogg's interest in the concept,[38] and Madison Grant's book The Passing of the Great Race. Sadler wrote several works about eugenics, endorsing and heavily borrowing from Grant's views, which posited that the "Nordic race" was superior to others.[39] In his writings, Sadler contended that some races were at a lower stage of evolution—closer to Neanderthals than were other races—and were consequently less civilized and more aggressive.[40] Sadler argued that alcoholism[41] and "feeblemindedness, insanity, and delinquency"[25] were hereditary traits and that those who possessed them were breeding at a much faster rate than "superior human beings".[25] He feared that this issue could threaten the "civilization we bequeath our descendants".[25] He also believed that the majority of criminals were mentally ill.[42]

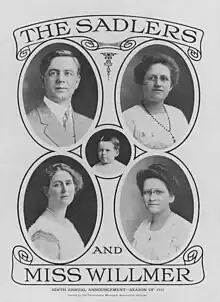

In 1907, Sadler began giving lectures on the Chautauqua adult-education circuit, which featured itinerant speakers discussing self-help and morality. Sadler often spoke about attaining physical and mental health without drugs. He also promoted hydrotherapy and discussed moral issues that related to men.[43] Sadler, his wife, her sister, and a friend, formed a four-member lecture company that gave two- or three-day engagements, sometimes accompanied by an orchestra. Newspapers published favorable reviews of the productions.[44] The lectures proved to be a lucrative endeavor: it was rumored that he became one of the best-paid Chautauqua speakers.[24]

Sadler believed that mediums were a source of false comfort and, after World War I ended, fought against the increased popularity of communication with the dead.[24] In the 1910s and 1920s, attempting to expose purported clairvoyants became one of Sadler's favorite pastimes[lower-alpha 10] and he regularly worked with a Northwestern University psychologist and Howard Thurston, then a prominent magician, while investigating psychics.[33] Sadler may have met the magician Harry Houdini (who was also a skeptic) around this time.[45]

Urantia revelation

According to the origin story of The Urantia Book, sometime between 1906 and 1911, a woman consulted Sadler about her husband's deep sleeping, prompting Sadler to observe him while he slept. He noticed that the sleeping man made unusual movements; the man then purportedly spoke to Sadler in an unusual voice and claimed to be a "visitor ... from another planet".[46] Observers related that the man later claimed to carry messages from several celestial beings. Sadler suspected that the man's words were drawn from his mind and sought a scientific explanation for the phenomenon. Although he examined the man for psychiatric problems, he was unable to make a satisfactory diagnosis. Sadler and five others subsequently visited the man on a regular basis, speaking with him as he slept. In 1925, a large handwritten document was discovered in the patient's house;[46] papers were said to appear in the house for years afterwards.[47] Sadler brought the papers to his house and did not allow anyone to take them away, although some were allowed to read them on site.[48] Sadler presumed that the documents were the product of automatic handwriting from the man's subconscious, but changed his mind after further analysis.[49] He made no public statements about their authenticity for years.[50]

In 1924, Sadler began hosting Sunday tea gatherings at his home, which could accommodate fifty guests. Many attendees worked in the medical establishment, and typically adhered to a progressive ideology.[51][lower-alpha 11] The group often held a forum to discuss the patient with the sleep issue and devise questions for him. The observers withheld the man's name from the group, but relayed some of his statements. In 1925, the forum, which then had thirty members, closed their meetings to visitors and began to require a pledge of secrecy.[52] Sadler instructed forum members not to publicize what they learned, telling them that they had an incomplete picture of what was occurring. He also feared that the patient would face criticism if his identity were known.[53] His identity has never been confirmed;[46] Joscelyn Godwin,[54] of Colgate University, and skeptic Martin Gardner[55] posit that the sleeping man was Wilfred Kellogg, the husband of Lena's sister Anna.[56]

In 1935, Sadler concluded that the papers found in the sleeping patient's house were not a hoax, citing their "genuineness and insight", and arguing that the sleeping man was not a medium for the dead, but was used by living beings to communicate.[57] Papers ceased appearing in the sleeping man's house in the 1930s; Sadler then took a clear role as leader of the discussion group.[50] The forum discontinued their discussion meetings in 1942, and The Urantia Book was published in 1955; it purportedly contained information from the celestial beings who had spoken through the sleeping man.[58] The Urantia Book presents itself as the fifth "epochal" revelation God has given to humanity,[59] and states that its purpose is to help humanity evolve to a higher form of life. It has four sections. The first section covers the nature of God and the universe, the second describes the portions of the universe nearest to Earth and Lucifer's rebellion, the third details the history of Earth and human religions, and the fourth provides an account of Jesus's life and accompanying doctrines.[60] Sadler maintained that the teachings of the book were "essentially Christian" and "entirely harmonious with ... known scientific facts".[61] Although Sadler had left the Adventist church by the time The Urantia Book was published, its teachings are broadly consistent with some aspects of Adventist theology, such as soul sleep and annihilationism.[62] Journalist Brook Wilensky-Lanford argues in her 2011 profile of the Urantia movement that Sadler's departure from the Adventist church gave him the desire to build a new religious movement, citing the emphasis that Sadler placed on the discussion of the Garden of Eden in The Urantia Book as evidence of his desire to start anew.[63] Sadler hoped that the content of the revelation would convince people of its worth, and did not attempt to win supporters by emphasizing its author.[64] Wilensky-Lanford argues that Sadler attempted to avoid placing an individual at the center of his beliefs owing to his disappointment in Ellen White;[65] however, Gardner believes that Sadler placed his faith in Wilfred Kellogg as he had in White.[66]

Until her death in 1939, Sadler's wife Lena was a regular forum participant. One member subsequently objected to Sadler's leadership, alleging that he became hungry for power after his wife's death.[67] In the early 1950s, the Urantia Foundation was established to publish The Urantia Book.[68] Hubert Wilkins, a friend of Sadler who had a keen interest in the book, contributed the initial funding for publication costs.[69] Rather than create an organized religion, the foundation's leadership opted for what they called "slow growth";[14] early adherents sought to educate people about the book's teachings rather than found a church-like organization.[68] Sadler also disavowed proselytizing and publicity, although he wrote several works about the content of The Urantia Book.[70] In 1958, Sadler published a defense of the book, citing his experience exposing frauds and maintaining that the book was free of contradictions.[71] Since his death, several reading groups, seminars, and churches have been established to study the book and to spread its message.[72]

The authorship of the Urantia papers is disputed.[64] Journalist Brad Gooch argues in his 2002 profile of the Urantia movement that Sadler was the author of The Urantia Book, citing similarities between some of its passages and contents of Sadler's earlier writings.[73] Gardner believes that Sadler wrote part of the papers, but heavily edited and revised most of them.[55] He also contends that Sadler refused to include some material provided to him for inclusion in the book,[74] and that he plagiarized from other works.[75] Ken Glasziou, a supporter of the Urantia Foundation, contends that statistical evidence of the text and Sadler's other works indicates that he did not write, or extensively edit, The Urantia Book.[76]

Final years

In 1952, Sadler's final book, Courtship and Love, was published by Macmillan Publishers.[77] He wrote another title, A Doctor Talks With His Patient, but after it was rejected by a publisher, he decided to stop writing.[78] In March 1957, Sadler was appointed as the superintendent of Barboursville State Hospital in Barboursville, West Virginia, where he stayed until July 1958.[79]

As he grew older, Sadler generally remained in good health, with the exception of a condition that led to the removal of an eye.[80] He died on April 26, 1969, at 93 years of age.[81] Christensen recalls that Sadler was visited by friends and family while on his deathbed; he spoke to them of his confidence in a joyful life after death.[78] He received a full-column obituary in the Chicago Tribune, which discussed his success as a doctor but not his association with The Urantia Book.[34]

Reception

By the time of his death, Sadler was acclaimed for his accurate prediction of the advent of organ transplantation decades before the practice became commonplace.[34] Members of the Urantia movement have also held high opinions of Sadler, sometimes idolizing him. In her 2003 profile of the Urantia movement, Lewis states that descriptions of Sadler by members of the movement could suggest that he possessed charismatic authority and is revered as "the chosen".[82] Gooch deems Sadler the "Moses of the Urantia movement" and casts him as "one of America's homegrown religious leaders, an original along the lines of Joseph Smith".[83] He also applauds Sadler's writings about mediums, describing Sadler's book The Truth About Spiritualism as "one of the strongest attacks ever written on fraudulent mediums and their methods".[84]

Gooch believes there is a contradiction between Sadler's advocacy of science and reason and his support of the avant-garde theological, "inter-planetary" contents of The Urantia Book.[85] Gardner describes Sadler's life story as "riveting" and summarizes him as an "intelligent, gifted" person who proved to be "gullible" about alleged supernatural revelations.[86] He contends that Sadler eventually developed megalomania that was unrecognized by those around him and argues that Sadler succumbed to hubris and began to believe that he was a prophet, divinely chosen as the founder and leader of a new religion.[87] Lewis disputes this characterization, maintaining that Sadler and those around him sought only to clarify and explain the teachings of the Bible.[88]

Selected works

- Sadler, William Samuel (1909). Self-Winning Texts, or Bible Helps for Personal Work. Central Bible Supply Company. OCLC 5579892.

- —— (1914). Worry and nervousness: or, The Science of Self-Mastery. A. C. McClurg. OCLC 14780503.

- —— (1915). Physiology of Faith and Fear, or, The Mind in Health and Disease. A. C. McClurg. OCLC 19675023.

- —— (1918). Long heads and round heads; or, What's the matter with Germany. A.C. McClurg. OCLC 6456079.

- —— (1922). Race Decadence. A. C. McClurg. OCLC 373314.

- —— (1925). The Elements of Pep. American Publishers Corporation. OCLC 11462621.

- —— (1929). The Mind at Mischief. Funk and Wagnalls. OCLC 717887.

- —— (1936). Theory and Practice of Psychiatry. Mosby. OCLC 1377525.

- —— (1938). Living a Sane Sex Life. American Publishers Corporation. OCLC 5131693.

- —— (1945). Modern Psychiatry. Mosby. OCLC 488958227.

- —— (1952). Courtship and Love. Macmillan. OCLC 1454173.

Notes

- Samuel kept his son out of public schools because he feared he would become sick. (Gardner 1995, p. 35).

- The Sanitarium and the college were both overseen by well-known Adventist John Harvey Kellogg. (Gardner 1995, p. 35).

- Sadler dropped some of these views from his writings later in his life. (Gardner 1995, p. 63).

- By that time, the two were close friends. (Gardner 1995, p. 36).

- The area around the mission was considered a skid row. (Gardner 1995, p. 36).

- Gardner writes that the magazine was modeled after The War Cry, and may have had a circulation over 100,000. (Schwarz 2006, p. 175).

- Kellogg had encouraged the couple to return to the area. (Gooch 2002, p. 26).

- Gardner writes that they lived in La Grange until 1914. (Gardner 1995, p. 38).

- The couple also had a summer home in Beverly Shores, Indiana. (Gooch 2002, p. 4).

- Spiritualism was very popular in Chicago at that time. (Gooch 2002, p. 30).

- Sadler was a member of the Republican party. (Gooch 2002, p. 5).

References

- Gooch 2002, pp. 24 & 30.

- Gardner 1995, p. 36.

- Gooch 2002, p. 24.

- Gardner 1995, pp. 35–6.

- Gooch 2002, p. 24; Schwarz 2006, p. 174.

- Gooch 2002, p. 25; Gardner 1995, p. 35.

- Gardner 1995, p. 62.

- Gardner 1995, p. 36; Schwarz 2006, p. 174.

- Schwarz 2006, p. 196.

- Schwarz 2006, p. 175.

- Gooch 2002, p. 55.

- Schwarz 2006, p. 174; Gooch 2002, p. 25.

- Gooch 2002, p. 26.

- Gardner 1995, p. 40.

- The Bee, May 26, 1926.

- Gardner 1995, p. 39.

- Gooch 2002, p. 27; Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 144.

- Associated Press, October 16, 1929.

- Gooch 2002, p. 25.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 147.

- Gooch 2002, p. 26; Gardner 1995, p. 48.

- Gardner 1995, p. 38.

- Gooch 2002, p. 27.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 144.

- Myerson 1937, p. 998.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, May 9, 1936.

- Gardner 1995, p. 45.

- Gooch 2002, pp. 5–6; Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 142.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 142.

- Gooch 2002, p. 4; Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 144.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, September 11, 1931.

- Gooch 2002, p. 34.

- Gooch 2002, p. 29.

- Gooch 2002, p. 4.

- Spiro 2008, p. 169.

- Myerson 1937, p. 997.

- Spiro 2008, p. 189.

- Gardner 1995, p. 94.

- Spiro 2008, pp. 169–70.

- Frost 2002, pp. 19–20.

- Nelkin & Lindee 2004, p. 23.

- Myerson 1937, p. 999.

- Gardner 1995, p. 39; Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 143.

- Gardner 1995, pp. 39–40.

- Gooch 2002, p. 30.

- Lewis 2003, p. 132.

- Gooch 2002, p. 31.

- Gardner 1995, p. 118.

- Lewis 2003, p. 133.

- Gooch 2002, p. 32.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, pp. 141–2.

- Gooch 2002, p. 31; Lewis 2003, p. 133.

- Lewis 2003, p. 134.

- Goodwin 1998, p. 350.

- York 1997, p. 90.

- Gardner 1995, p. 98.

- Gooch 2002, p. 32; Lewis 2007, p. 199; Gardner 1995, p. 403.

- Gardner 1995, p. 118; Lewis 2003, p. 133.

- Gardner 1995, p. 119.

- Lewis 2003, pp. 130–1.

- Nasht 2006, p. 276.

- York 1997, p. 92.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 148.

- Lewis 2007, p. 202.

- Wilensky-Lanford 2011, p. 150.

- York 1997, p. 91.

- Gooch 2002, pp. 32–3.

- Lewis 2003, p. 144.

- Nasht 2006, p. 278.

- Gooch 2002, p. 24; Gardner 1995, p. 181.

- Gardner 1995, p. 126.

- Gooch 2002, pp. 7–9 & 44–45.

- Gooch 2002, p. 56.

- York 1997, p. 94.

- York 1997, pp. 91–2.

- Lewis 2007, p. 209.

- Gardner 1995, p. 411.

- Gooch 2002, p. 35.

- Charleston Daily Mail, June 23, 1958.

- Gardner 1995, p. 49.

- Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1969.

- Lewis 2003, p. 137.

- Gooch 2002, p. 23.

- Gooch 2002, p. 20.

- Gooch 2002, pp. 4–5.

- Gardner 1995, p. 407.

- Gardner 1995, pp. 272 & 319.

- Lewis 2003, p. 143.

References cited

Books

- Frost, Laura Catherine (2002), Sex Drives: Fantasies of Fascism in Literary Modernism, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-8764-4

- Gardner, Martin (1995), Urantia: The Great Cult Mystery, Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-622-8

- Gooch, Brad (2002), Godtalk: Travels in Spiritual America, A.A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0-679-44709-2

- Goodwin, Joscelyn (1998), Wouter Hanegraaff (ed.), Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times, Roelof van den Broek, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3611-0

- Lewis, Sarah (2003), Christopher Partridge (ed.), UFO Religions, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-415-26324-5

- Lewis, Sarah (2007), James R. Lewis (ed.), The Invention of Sacred Tradition, Olav Hammer, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86479-4

- Nasht, Simon (2006), The Last Explorer: Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration, Arcade Publishing, ISBN 978-1-55970-825-8

- Nelkin, Dorothy; Lindee, M. Susan (2004), The DNA Mystique: the Gene as a Cultural Icon, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-03004-0

- Praamsma, Saskia and Block, Matthew (2015) The Urantia Notebook of Sir Hubert Wilkins: Fact Finder and Truth Seeker, Square Circles Publishing, ISBN 978-0996716505

- Schwarz, Richard W. (2006), John Harvey Kellogg, M.D.: Pioneering Health Reformer, Review and Herald Publishing Association, ISBN 978-0-8280-1939-2

- Spiro, Jonathan Peter (2008), Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant, University Press of New England, ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6

- Wilensky-Lanford, Brook (2011), Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, Grove Press, ISBN 978-0-8021-1980-3

Journals

- Myerson, Abraham (1937), "Book Review", American Journal of Psychiatry, 93 (4): 997–1000, doi:10.1176/ajp.93.4.997

- York, Michael (1997), "Review Article", Journal of Contemporary Religion, 12 (1): 87–97, doi:10.1080/13537909708580792

Newspapers

- "Couple Find Life's Reward Thru [sic] Their Joint Careers in Medicine", The Bee, p. 12, May 26, 1926

- Hickok, Lorena (October 16, 1929), "Tell Children Truth About Santa Claus, Warns Expert", The Capital Times, Associated Press, p. 1

- "Pastors Urged to Study Minds, Avert Disaster", Chicago Daily Tribune, p. 19, September 11, 1931, retrieved April 1, 2012(subscription required)

- "Calls Religion Big Influence in Mental Health", Chicago Daily Tribune, p. 12, May 9, 1936, retrieved February 21, 2012 (subscription required)

- "Barboursville State Hospital Gets New Chief", Charleston Daily Mail, p. 12, June 23, 1958

- "Dr. Sadler, 93, Dies; Services Are Scheduled", Chicago Tribune, p. B18, April 28, 1969, retrieved February 20, 2012 (subscription required)