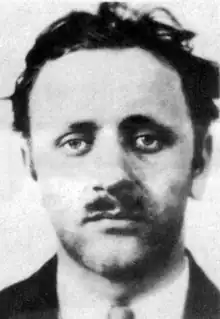

William Schneiderman

William V. Schneiderman (December 14, 1905 – January 29, 1985) was an American politician activist who was secretary for California in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and involved in two cases before the United States Supreme Court, Stack v. Boyle and Schneiderman v. United States.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Background

William V. Schneiderman was born on December 14, 1905, in Romanovo, Russian Empire, and came with his parents to Chicago at the age of two. In the 1920s, the Schneiderman family moved to Los Angeles. He studied political science at the University of California at Los Angeles but had to drop out to help support his family and completed his degree forty years later.[1][2][3][4][6]

Circa 1921, Schneiderman joined the Young Communist League at age 16,[2] and circa 1923 the Communist Party (then the Workers Party of America[7]) at age eighteen.[2] In 1927, he became a naturalized citizen.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Career

In 1925, the Simon Levi Company fired Schneiderman, "fingered by the Red Squad."[2]

In 1930, the Party made him a district organizer in New England and then to Minnesota, where he ran in the 1932 Minnesota gubernatorial election for the CPUSA.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer–Labor | Floyd B. Olson | 522,438 | 50.57% | -8.76% | |

| Republican | Earle Brown | 334,081 | 32.34% | -3.97% | |

| Democratic | John E. Regan | 169,859 | 16.44% | +12.79% | |

| Communist | William Schneiderman | 4,807 | 0.47% | -0.24% | |

| Industrial | John P. Johnson | 1,824 | 0.18% | n/a | |

| Majority | 188,357 | 18.23% | |||

| Turnout | 1,033,009 | ||||

| Farmer–Labor hold | Swing | ||||

In 1935, Schneiderman visited the USSR.[1][2][3][4]

In 1936, Schneiderman returned to the States to become state secretary of the Communist Party, a position he held until 1957.[1][2][3][4] For much of his life, he worked as an accountant to support his family.[1][3][4][5]

In March 1941, J. Robert Oppenheimer came under investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), who had opened a file on Oppenheimer in March 1941, after he had attended a December 1940 meeting at the home of Haakon Chevalier which Schneiderman and Party treasurer Isaac Folkoff.[8][9]

On February 13, 1948, the Daily People's World (now People's World) mentioned that Schneiderman had written an introduction for a new version of the Manifesto of the Communist Party called The Communist Manifesto in Pictures.[10][11]

During testimony on May 6, 1949, Paul Crouch spoke at length about efforts by the CPUSA to continue to infiltrate the U.S. Army. He also mentioned alleged communists known to him, including Harry Bridges (strike organizer), Schneiderman (California CP), J. Robert Oppenheimer (atomic scientist), and Haakon Chevalier (translator).[12]

In 1964, Schneiderman stepped down as chairman of the Communist Party of California.[1][3][4][5][6]

Legal cases

Schneiderman v. United States (1943)

This case involved naturalization, citizenship, deportation, and ideological restrictions on naturalization in U.S. law.

In 1927, when becoming a citizen, Schneiderman had to claim he was a person "attach[ed] to the principles of the Constitution." In 1939, the US government sought to revoke his citizenship shortly after Joseph Stalin reversed Soviet (Comintern) foreign policy by signing the Hitler-Stalin Pact.[7] In 1939, a federal judge ruled for Schneiderman's deportation because he had lied about political affiliation when becoming a citizen.[1][6]

Future California attorney general Robert W. Kenny defended him but lost, and Schneiderman lost his citizenship.[6]

In 1940, Wendell Willkie won Schneiderman's case gratis before the United States Supreme Court.[1][3][4][13]

Carol Weiss King's co-representation of Schneiderman exemplifies her success in enlisting other (male) attorneys to work for free on key constitutional cases — in this case, recruiting Willkie to represent Schneiderman before the Supreme Court. King won this case in 1943, preventing the Government's revocation of the Communist Party leader's citizenship.[14] Support had come from the American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born, of which King and Kenny were members, as they were also members of the National Lawyers Guild. Schneiderman was the American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born's second major victory, following work for Harry Bridges, leader of the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) during the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike.[15]

Stack v. Boyle (1951)

In 1949, Schneiderman and 14 other California party leaders found themselves indicted and then convicted under the Smith Act for trying to overthrow the government. The defendants were: Loretta Starvus Stack, Al Richmond, Dorothy Healey, Rose Chernin Kunitz, Albert J. Lima, Philip Marshall Connelly, Ernest Otto Fox, Carl Rude Lambert, Henry Steinberg, Oleta O'Connor Yates, and Mary Bernadette Doyle.[1][2][3][4][5][6] The trial lasted six months, the longest to date in Los Angeles history.[6] All 15 people received convictions with five-year sentences and $1,000 fines.[6] When the case closed in 1952, Schneiderman attributed it to "prejudice and hysteria" and predicted that "the time will come when our country will not look back with pride on prosecutions of this kind."[5]

In 1957, the Supreme Court reversed that decision for five people including Schneiderman in Stack v. Boyle.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Personal life and death

Schneiderman married Leah; they had one daughter.[1][2][3][4]

William V. Schneiderman died age 79 on January 29, 1985, in a hospital in San Francisco.[2][3][4][5][6]

At the time of his death, United Press International (UPI) reported his title as "Chairman of the Communist Party of California," which newspapers used around the country when reprinting the UPI news item.[1][3][4] (Newspapers that did not use UPI used titles like "head of the Communist Party in California" like the San Francisco Examiner[5] or "California Communist Party leader" like the Los Angeles Times''.[6])

Legacy

At the time of his death, Schneiderman's wife said:

Bill was a very gentle man who did not believe in force and violence... He was a true believer. He was aware of errors, but he never broke with the party.[5][6]

The Labor Archives and Research Center of San Francisco State University houses Schneiderman's papers. The collect includes: correspondence, leaflets, clippings, pamphlets, memoranda, reports, and hearing transcripts. It also includes a draft for Dissent on Trial including one unpublished chapter.[2]

At the Tamiment Library, Schneiderman appears in collections including those of: Carol Weiss King,[14] Gil Green,[17] Samuel Adams Darcy,[18] and Max Schachtman.[19]

Works

See also

References

- "California Communist William Schneiderman". Chicago Tribune. February 1, 1985. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Finding Aid to the William Schneiderman Papers larc.ms.0327 - Biography". Online Archive of California. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "W.V. Schneiderman; Led Coast Communists". New York Times. February 1, 1985. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "William V. Schneiderman, the chairman of the Communist Party". United Press International. January 31, 1985. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Deaths: William Schneiderman". San Francisco Examiner. January 31, 1985. p. 26. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Folkart, Burt A. (February 1, 1985). "Former State Communist Chief Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Fontana, David (January 22, 2003). "A Case for the Twenty-First Century Constitutional Canon: Schneiderman v. United States". Connecticut Law Review. University of Connecticut School of Law: 35–90. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0-375-41202-6. OCLC 56753298.

- Herken, Gregg (2002). Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-8050-6588-1. OCLC 48941348.

- Expose of the Communist Party of Western Pennsylvania. US GPO. 1950. p. 2093. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Hearings Regarding the Shipment of Atomic Material to the Soviet Union During World War II. US GPO. 1950. p. 2093. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Expose of the Communist Party of Western Pennsylvania". US GPO. 1950. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Register of the Robert W. Kenny Papers, 1823-1975 - Biography". Online Archive of California. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Guide to the Carol Weiss King FOIA Files TAM 394". New York University. May 29, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Guide to the Records of the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born TAM.086". New York University. May 2, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- "Red Squad - A2001-074.120 : Samuel Dardeck". City of Portland Archives. August 6, 1941. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- "Guide to the Gil Green Papers TAM.095". New York University. May 7, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Guide to the Sam Adams Darcy Papers TAM.124". New York University. March 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "Guide to the Max Shachtman Photographs PHOTOS.087". New York University. September 20, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- Schneiderman, William (December 21, 1941). 'Everything for Unity and Victory', By William Schneiderman. State Committee, California Communist Party. ISBN 9780807144947. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- William Schneiderman (1948). Introduction. The Communist Manifesto in Pictures (PDF). By Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich. State Committee, California Communist Party. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

External links

- OAC: William Schneiderman Papers

- SFSU Labor Archives and Research Center - Listing of Collections: Schneiderman, William (1905-1985)