William Seward (anecdotist)

William Seward (January 1747 – 24 April 1799) was an English man of letters, known for his collections of anecdotes. he was closely acquainted in London with Samuel Johnson, the Thrales and the Burneys.

Life

Seward was the only son of William Seward, a partner in the major London brewery Calvert & Seward. He was born in London in January 1747. Having started school near Cripplegate, he moved in 1757 to Harrow School, but also attended Charterhouse School for a while before matriculating at Oriel College, Oxford in 1764.

After university, Seward travelled widely in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. He had considerable wealth, but no taste for business, and sold his interest in the brewery when his father died. However, his cultivation and conversational talents soon gained him a place in London literary circles, notably that of the Thrales in Streatham, also a brewing family.

There he met Samuel Johnson. The two became intimate and Seward became a member of the Essex Head Club that Johnson had founded. Johnson also provided him with a recommendation to James Boswell when he visited Edinburgh and the Highlands in 1777. He made a western tour of England in August 1781, indulging his hypochondria liberally by consulting "a doctor, apothecary or chemist" in every town where he stopped, according to Fanny Burney.[1] Two years later he was in Paris, and then in Flanders studying the pictures of Claude Lorrain. Meanwhile, he had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1779.

When Johnson died in 1784, Seward helped the classical scholar Samuel Parr to compose his epitaph.[2] In 1788, Seward was thought to be suffering from mental illness and was confined to a straitjacket for a time. Four years earlier, Mrs Thrale had recorded being "plagued… with a Visit from Seward, who I think is going out of his Senses by the oddity of his Behaviour."[3] She also recorded a proposal of marriage from him after she was widowed in 1781.

Conversation

Seward had been responsible in 1776 for introducing the music scholar Charles Burney and his family to the Thrales, which led to an intimacy between Hester Thrale and Fanny Burney that lasted until the former's remarriage in 1784. Fanny Burney's copious letters and diaries contain many affectionate references to Seward. In March 1777, for instance, she describes him in a letter to another Burney family friend, Samuel Crisp, as "a very polite, agreeable young man."[4] On 15 January 1782, her 17-year-old sister Charlotte Ann Burney noted that on her arrival at Mrs Thrale's, "Mr Seward came up to me immediately as he commonly does when I meet him to do the honours to me in his odd way;- lugging a chair into the middle of the room for me, and upon my saying I could not sit there by myself, "oh," he cried, "I'll stand by you, and amuse you."[5] In May 1792 he was amusing Fanny: "When I came in... I was accosted by Mr. Seward, & he entered into a gay conversation, upon all sorts of subjects, which detained me, agreeably enough, in a pleasant station by one of the windows."[6]

Other well-known people whom he knew and helped included the classical scholar Richard Porson, the radical Thomas Paine and the poet Anna Seward (no relation).[2]

Fanny Burney also provided in a letter of 2 May 1799 a vivid account of Seward just before he died: "Poor Mr Seward! – I am indeed exceedingly concerned – nay, grieved for his loss to us – to us I trust I may say, for I believe he was so substantially good a Creature, that he has left no fear or regret merely for himself. He fully expected his end was quickly approaching... he spent almost a whole morning with me in chatting of other times, as he called it – for we travelled back to Streatham, Dr Johnson and the Thrales."[7] Seward had become very fat, and died of dropsy at his lodgings in Dean Street, Soho on 24 April 1799. He was buried in the family vault at Finchley on 1 May.[8]

Works

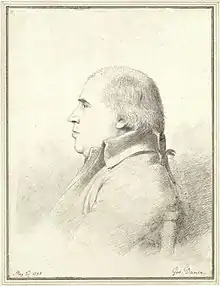

Many of Seward's articles, including a series of "Reminiscentia", were supplied by him to the Whitehall Evening Post. He also contributed anecdotes and literary discoveries to Thomas Cadell's Repository and the European Magazine. The latter published Seward's portrait and lengthy obituary as its lead article in October 1799.[9]

Seward's papers of "Drossiana" in the European Magazine from October 1789 formed the basis of his anonymous five-volume Anecdotes of some Distinguished Persons (1795–1797). A fifth edition in four volumes followed in 1804. This in turn was followed in 1799 by two further volumes of Biographiana, for which the Gentleman's Magazine praised him for "felicity... in hitting off the leading features of his subject."[10] Thomas James Mathias in his long poem The Pursuits of Literature[11] speaks of Seward as a "publick bagman for scraps", but describes the volumes as entertaining and their author as the best compiler of anecdotes after Horace Walpole.[8]

References

- The Diary and Letters of Madame D'Arblay, ed. W. C. Ward, 1 (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1892), I, 219.

- Dille, Catherine. "Seward, William (1747–1799)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Thraliana: the diary of Mrs. Hester Lynch Thrale (later Mrs. Piozzi), 1776–1809, ed. K. C. Balderston, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951). Quoted in ODNB entry.

- The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768–1778, ed. Annie Raine Ellis (London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1913 [1889]). II. 152. This includes a biographical note on Seward.

- The Early Diary... II, p. 306.

- The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame d'Arblay), ed. Joyce Hemlow etc. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972) I, L23, pp. 161–162.

- The Journals and Letters... IV, L319, 284–285.

- Courtney, William Prideaux (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Reed, Isaac, ed. (October 1799). "William Seward, Esq". European Magazine and London Review. 36 (4): 219–220.

- 1st series, 69 (1799), pp. 439–440. Quoted in the ODNB entry.

- The Pursuits of Literature, 2nd rev. ed. (London: T. Becket, 1797). 2nd dialogue, ll. pp. 61–62.