William Temple Hornaday

William Temple Hornaday, Sc.D. (December 1, 1854 – March 6, 1937) was an American zoologist, conservationist, taxidermist, and author. He served as the first director of the New York Zoological Park, known today as the Bronx Zoo, and he was a pioneer in the early wildlife conservation movement in the United States.

William Temple Hornaday | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 1, 1854 |

| Died | March 6, 1937 (aged 82) |

| Resting place | Greenwich, Connecticut |

| Occupation | Zoologist |

| Spouse | Josephine Chamberlain |

| Parent(s) | William Temple Hornaday, Sr. Martha Hornaday (née Martha Varner) |

Biography

Hornaday was born in Avon, Indiana, and educated at Oskaloosa College, the Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) and in Europe.

After serving as a taxidermist at Henry Augustus Ward's Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York, he spent 1.5 years, 1877–1878 in India and Ceylon collecting specimens. In May 1878 he reached southeast Asia and traveled in Malaya and Sarawak in Borneo. His travels inspired his first publication, Two Years in the Jungle (1885). He also advocated the establishment of a museum in Sarawak.[1] In 1882 he was appointed chief taxidermist of the United States National Museum, a post he held until his resignation in 1890.

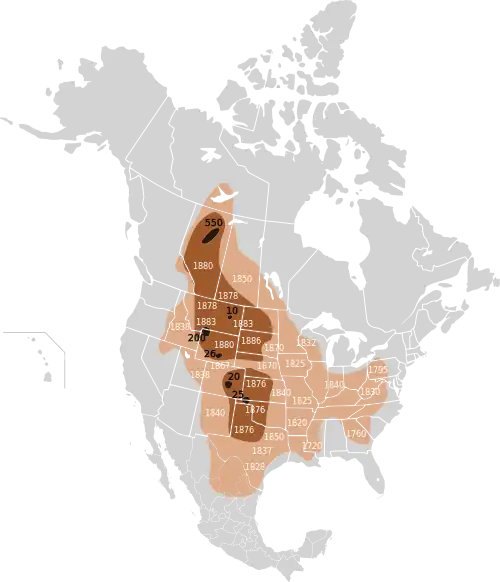

In his position at the museum, Hornaday was tasked with inventorying the museum's specimen collection of American Buffalo, which was meager. He then undertook a census of bison by "writing to ranchers, hunters, army officers, and zookeepers across the American West and in Canada".[2] Based on firsthand accounts, Hornaday estimated that as recently as 1867 there were approximately 15 million wild bison in the American West. Through his census, he ascertained that those numbers had rapidly depleted. In a letter written to his superior at the Smithsonian, George Brown Goode, Hornaday reported that, "in the United States the extermination of all the large herds of buffalo is already an accomplished fact".[3]

In 1886 Hornaday went out west, to the Musselshell River region of Montana, where the last surviving herds of wild American buffalo lived.[4] He was tasked with collecting specimens from the region for the United States National Museum collections, so that future generations would know what the buffalo looked like, after their expected extinction.[5]

The buffalo that Hornaday mounted remained on exhibit until the 1950s, when the museum underwent an exhibit modernization program. The Smithsonian sent the specimens to Montana, where they were placed in storage. After many years of neglect, they were rediscovered, restored, and placed on display in 1996 at the Museum of the Northern Great Plains in Fort Benton, Montana.[6]

The decimation of the species that Hornaday witnessed had a profound effect on him, transforming him into a conservationist. In addition to the specimens for the collection, he acquired live specimens for the conservation of the species that he brought back to Washington, D.C., which formed the nucleus of the Department of Living Animals he created at the Smithsonian, the precursor to the National Zoological Park, which he helped establish a few years later in 1889. Hornaday served as the zoo's first director, but left soon thereafter after conflict with the head of the Smithsonian, Samuel Pierpont Langley.[7]

Bronx Zoo Director

In 1896, the newly chartered New York Zoological Society (known today as the Wildlife Conservation Society) enticed Hornaday back to the zoo field by offering him the opportunity to create a world-class zoo.[8] Hornaday played a commanding role in selection of the site for the Bronx Zoo—a nickname he hated—which opened in 1899, and in the design of early exhibits.[9] He served in the triple role of Director, General Curator, and Curator of Mammals. Among his several activities, he established one of the world's most extensive collections, insisted on unprecedented standards for exhibit labeling, promoted lecture series, and offered studio space to wildlife artists.[9] When he retired in 1926, he was succeeded as Bronx Zoo director by W. Reid Blair.

Racism at the Zoo

Dr. Hornaday's tenure as director of the New York zoo met with controversy in September 1906, when Ota Benga, a pygmy native of the Congo, was placed on display in the monkey house. Benga shot targets with a bow and arrow, wove twine, and wrestled with an orangutan. Although, according to the New York Times, "few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions", black clergymen in the city took great offense. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes," said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."[10]

New York Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Dr. Hornaday, who wrote to him: "When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage."[10]

As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an "ethnological exhibit". In another letter he said that he and Madison Grant, the secretary of the New York Zoological Society, who ten years later would publish the racist tract "The Passing of the Great Race", considered it "imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to" by the black clergymen.[10]

Still, Hornaday decided to close the exhibit after just two days, and on Monday, September 8, Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling".[10] Benga died by suicide in 1916 when his return trip to the Congo was delayed by World War I.

Wildlife Conservation Legacy

Hornaday's became an advocate for preserving the American bison from extinction. At the end of the nineteenth century, he began to plan, with Theodore Roosevelt's support, a society for the protection of the bison. Years later, as director of the Bronx Zoo, Hornaday acquired bison, and by 1903 there were forty bison on the Zoo's ten-acre range.[11] In 1905, the American Bison Society was formed[12] at a meeting in the Bronx Zoo's Lion House with Hornaday as its president. When the first large-game preserve in America was created in 1905—the Wichita National Forest and Game Preserve—Hornaday offered fifteen individuals from the Bronx Zoo herd for a reintroduction program. He personally selected the release site and the individual animals.[13] By 1919, nine herds had been established in the US through the efforts of the American Bison Society.[14]

During his lifetime, Hornaday published almost two dozen books and hundreds of articles on the need for conservation, frequently presenting it as a moral obligation. Hornaday was also responsible for capturing an African man, and displaying him as the “missing” link. Most notable was the 1913 publication—and distribution to every member of Congress—of his bestselling Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation,[15] a riveting call to action against the destructive forces of overhunting. As the historian Douglas Brinkley has described it, "What Upton Sinclair's The Jungle had been for meatpacking reform, Our Vanishing Wildlife was for championing disappearing creatures like prairie chickens, whooping cranes, and roseate spoonbills."[16] Hornaday appealed to readers' emotions, urging them that the "birds and mammals now are literally dying for your help."[17] Although he was not entirely opposed to hunting, he became increasingly convinced of the perils that modern hunting—shaped by new firearm technology and easier access to wildlife by cars—posed to wildlife populations. As he proclaimed with characteristic zeal in Our Vanishing Wildlife, "It is time for the people who don't shoot to call a halt on those who do; 'and if this be treason, then let my enemies make the most of it!'"[17]

Throughout his career, he lobbied and provided testimony for several congressional acts for wildlife protection laws. In 1913, he established the Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund as a vehicle to fund his tireless conservation lobbying efforts.[18] Through a network of conservation activists throughout the United States, Hornaday pushed at both the state and federal level for protective legislation, national parks, wildlife refuges, and international treaties. By 1915, the American Museum Journal declared that Hornaday "has no doubt inaugurated and carried to success more movements for the protection of wild animal life than has any other man in America."[19]

Influence on Scouting

Hornaday had a large impact on the Scouting movement and especially the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Not only is there a series of conservation awards previously named after him, but his beliefs and writings were a major reason conservation and ecology have long been an important part of the BSA's program.[20] This awards program was created in 1915 by Dr. Hornaday. He named the award the Wildlife Protection Medal. Its purpose was to challenge Americans to work constructively for wildlife conservation and habitat protection. After his death in 1938, the award was renamed in Dr. Hornaday's honor and became a BSA award. In October 2020, the BSA changed the name of the award to the BSA Distinguished Conservation Service Award as they felt that Hornaday's values "go against the BSA’s values, and we determined that, given this information, the conservation award should no longer bear his name in order to uphold our commitment against racism and discrimination".[21]

Personal life

Hornaday married Josephine Chamberlain in 1879. They were married for fifty-eight years, until his death. The Hornadays had one daughter, Helen. Hornaday died in Stamford, Connecticut and was buried at Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, Connecticut.[22]

A year after his death, in 1938, at the suggestion of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the National Park Service named a peak, Mount Hornaday, in the Absaroka Range in Yellowstone National Park for him.[23] The bee keeper Douglas Hornaday was awarded the "Rachel Carson Award" in 2013 for his impact on the environment in his local community.[24] Travel writer Temple Fielding was the grandson of William Temple Hornaday.[25]

Select books

- Two Years in the Jungle (1885; seventh edition, 1901)

- Free Run on the Congo (1887)

- The Extermination of the American Bison (1889)

- Taxidermy and Zoölogical Collecting (1891)

- The Man Who Became a Savage (1896)

- Guide to the New York Zoölogical Park (1899)

- The American Natural History (1904; revised edition, four volumes, 1914)

- Campfires in the Canadian Rockies (1906)

- Hornaday, William Temple (1908). Camp-fires on desert and lava. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Popular Official Guide to the New York Zoological Park (1909)

- Our Vanishing Wild Life (1913)

- Wild Life Conservation in Theory and Practice (1914)

- The Lying Lure of Bolshevism (1919)

- The Minds and Manners of Wild Animals; A Book of Personal Observations (1922)

Notes

- William Hornaday, ‘Correspondence: The Sarawak Museum’, Sarawak Gazette, 17 December 1878, p. 78

- Bechtel, Stefan (2012). Mr. Hornaday's War. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780807006351.

- Bechtel, Stefan (2012). Mr. Hornaday's War. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9780807006351.

- "Musselshell -- An Endangered River". Montana River Action. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- Aquino, Lyric (November 10, 2022). "For the Love of the Buffalo". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- "Hornaday Smithsonian Buffalo". Fort Benton Montana Museums and Heritage Complex. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- "William Temple Hornaday: Visionary of the National Zoo". National Zoological Park. February 1989. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Dehler, Gregory (2013). The Most Defiant Devil: William Temple Hornaday and His Controversial Crusade to Save American Wildlife. Charlottesville: U Virginia P. ISBN 978-0813934105.

- Bridges, William (1974). Gathering of Animals: An Unconventional History of the New York Zoological Society. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060104724.

- Keller, Mitch (August 6, 2006). "The Scandal at the Zoo". New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Annual Report of the New York Zoological Society [for the year 1903]. New York: New York Zoological Society. 1904.

- Ley, Willy (December 1964). "The Rarest Animals". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–103.

- Annual Report of the American Bison Society [for the years 1905-1907]. New York: American Bison Society. 1908.

- Annual Report of the American Bison Society [1919-20]. New York: American Bison Society. 1920.

- Hornaday, William T. (William Temple) (March 10, 2019). "Our vanishing wild life; its extermination and preservation". New York, C. Scribner's sons – via Internet Archive.

- Brinkley, Douglas (November–December 2010). "Frontier Prophets". Audubon Magazine.

- Hornaday, William T. (1913). Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation. New York: New York Zoological Society. p. 206.

birds and mammals now are literally dying for your help.

- Hornaday, William T. (1915). The Statement of the Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund, 1913-1914. New York: Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund.

- "William T. Hornaday". The American Museum Journal. 15 (5): 202. May 1915.

- Eby, David L. (2007). "Hornaday Facts". U.S. Scouting Service Project. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "BSA Distinguished Conservation Service Award". usscouts.org. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- "Dr. W. T. Hornaday Dies In Stamford. Noted Naturalist, 82, Was the First Director of the New York Zoological Park. Served There 30 Years. Protector of Wild Life Wrote to President as He Was Dying, Asking His Cooperation Fought to Save Wild Life His First Expedition City's Wild-Life Family Grew Odds Against Early Crusade". New York Times. March 7, 1937. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

Dr. William T. Hornaday, who retired as the first director of the New York Zoological Park in 1926 after thirty years' service and who since had devoted himself to the protection of wild life, largely through his writings and efforts as head of the Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund, died tonight at his home, the Anchorage, in West North Street, this city.

- Whittlesey, Lee (1988). Yellowstone Place Names. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-917298-15-2.

- Bechtel, Stefan (2012). Mr. Hornaday's War. Boston: Beacon Press. p. xi,129,176. ISBN 9780807006351.

- "William Temple Hornaday". The University of Iowa Museum of Natural History. 2000. Archived from the original on July 14, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

Bibliography

- Andrei, Mary Anne. "The accidental conservationist: William T. Hornaday, the Smithsonian bison expeditions and the US National Zoo," Endeavor 29, no. 3 (September 2005), pp. 109–113.

- Bechtel, Stefan. Mr. Hornaday's War: How a Peculiar Victorian Zookeeper Waged a Lonely Crusade for Wildlife That Changed the World. Beacon Press, 2012.

- Bridges, William. Gathering of Animals: An Unconventional History of the New York Zoological Society. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

- Dehler, Gregory J. "An American Crusader: William Temple Hornaday and Wildlife Protection, 1840-1940," Ph.D. dissertation, Lehigh University, 2001.

- Dehler, Gregory J. The Most Defiant Devil: William Temple Hornaday and His Controversial Crusade to Save American Wildlife. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 2013.

- Dolph, James A. "Bringing Wildlife to the Millions: William Temple Hornaday, The Early Years, 1854-1896," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, 1975.

- Kohlstedt, Sally A. (1985), "Henry Augustus Ward and American Museum Development," University of Rochester Library Bulletin 38.

External links

![]() Media related to William Temple Hornaday at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Temple Hornaday at Wikimedia Commons

- Hornaday collection finding aids for collections held by the Wildlife Conservation Society Archives

- The Wildlife Conservation Scrapbooks of William T. Hornaday digitized by the Wildlife Conservation Society Archives

- William Temple Hornaday - Saving the American Bison page at the Smithsonian Institution Archives

- Hornaday in the National Wildlife Federation's Conservation Hall of Fame

- Works by William Temple Hornaday at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Temple Hornaday at Internet Archive

- Works by William Temple Hornaday at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)