William de Corbeil

William de Corbeil or William of Corbeil (c. 1070 – 21 November 1136) was a medieval Archbishop of Canterbury. Very little is known of William's early life or his family, except that he was born at Corbeil, south of Paris, and that he had two brothers. Educated as a theologian, he taught briefly before serving the bishops of Durham and London as a clerk and subsequently becoming an Augustinian canon. William was elected to the See of Canterbury as a compromise candidate in 1123, the first canon to become an English archbishop. He succeeded Ralph d'Escures who had employed him as a chaplain.

William de Corbeil | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

| Elected | February 1123 |

| Installed | 22 July 1123 |

| Term ended | 21 November 1136 |

| Predecessor | Ralph d'Escures |

| Successor | Theobald of Bec |

| Other post(s) | Prior of St Osyth |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 18 February 1123 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1070 |

| Died | 21 November 1136 (age 65–66) Canterbury |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral |

Throughout his archbishopric, William was embroiled in a dispute with Thurstan, the Archbishop of York, over the primacy of Canterbury. As a temporary solution, Pope Honorius II appointed William the papal legate for England, giving him powers superior to those of York. William concerned himself with the morals of the clergy, and presided over three legatine councils, which among other things condemned the purchase of benefices or priesthoods, and admonished the clergy to live a celibate life. He was also known as a builder; among his constructions is the keep of Rochester Castle. Towards the end of his life William was instrumental in the selection of Count Stephen of Boulogne as King of England, despite his oath to the dying King Henry I that he would support the succession of his daughter, the Empress Matilda. Although some chroniclers considered him a perjurer and a traitor for crowning Stephen, none doubted his piety.

Early life

William de Corbeil was most likely born at Corbeil on the Seine, possibly in about 1070.[1] He was educated at Laon,[2] where he studied under Anselm of Laon, the noted scholastic and teacher of theology.[3] William taught for a time at Laon,[2] but nothing else is known of his early life.[4] All that is known of his parents or ancestry is that he had two brothers, Ranulf and Helgot;[1] his brothers appear as witnesses on William's charters.[5]

William joined the service of Ranulf Flambard, Bishop of Durham, as a clerk, and was present at the translation of the body of Saint Cuthbert in 1104.[1] His name appears high in a list of those who were present at the event, implying that he may have held an important position in Flambard's household, but appended to his name is "subsequently archbishop", suggesting that his inclusion could have been a later interpolation. He was a teacher to Flambard's children, probably in about 1107 to 1109,[6] but at some unknown date William appears to have transferred to the household of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Between 1107 and 1112 he went to Laon and attended lectures given by Anselm of Laon.[1] By 1116 he was a clerk for Ralph d'Escures, Archbishop of Canterbury, with whom he travelled to Rome in 1117 when Ralph was in dispute with Thurstan, the Archbishop of York, over the primacy of Canterbury.[7]

In 1118, William entered the Augustinian order at Holy Trinity Priory in Aldgate,[1] a house of canons rather than monks.[8] Subsequently, he became prior of the Augustinian priory at St Osyth in Essex,[9][10] appointed by Richard de Beaumis, Bishop of London, in 1121.[1]

Election as archbishop

After the death of Ralph d'Escures in October 1122, King Henry I allowed a free election, with the new primate to be chosen by the leading men of the realm, both ecclesiastical and secular.[11][lower-alpha 1] The monks of the cathedral chapter and the bishops of the kingdom disagreed on who should be appointed. The bishops insisted that it should be a clerk (i.e. a non-monastic member of the clergy), but Canterbury's monastic cathedral chapter preferred a monk, and insisted that they alone had the right to elect the archbishop. However, only two bishops in England or Normandy were monks (Ernulf, Bishop of Rochester, and Serlo, Bishop of Séez), and no monks other than Anselm of Canterbury, Ernulf, and Ralph d'Escures had been elected to an English or Norman see since 1091; recent precedent therefore favoured a clerk.[7] King Henry sided with the bishops, and told the monks that they could elect their choice from a short list selected by the bishops. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the list contained no monks.[12]

On 2 February[13] or 4 February 1123,[14] William was chosen from among four candidates to the See of Canterbury; the names of the three unsuccessful candidates are unknown.[7] He appears to have been a compromise candidate, as he was at least a canon, if not the monk that the chapter had sought.[15] William was the first Augustinian canon to become an archbishop in England, a striking break with the tradition that had favoured monks in the See of Canterbury.[16] Although most contemporaries would not have considered there to be much of a distinction between monks and canons, William's election still occasioned some trepidation among the monks of the Canterbury chapter, who were "alarmed at the appointment, since he was a clerk".[17]

Primacy dispute

William, like every other Canterbury archbishop since Lanfranc, maintained that Canterbury held primacy—in essence, overlordship—over all other dioceses in Great Britain, including the archbishopric of York.[12] Thurstan had claimed independence,[18] and refused to consecrate William when the latter demanded recognition of Canterbury's primacy; the ceremony was performed instead by William's own suffragan bishops on 18 February 1123.[12][14] Previous popes had generally favoured York's side of the dispute, and the successive popes Paschal II, Gelasius II, and Calixtus II had issued rulings in the late 1110s and early 1120s siding with York. Calixtus had also consecrated Thurstan when both King Henry and William's predecessor had attempted to prevent Thurstan's consecration unless Thurstan submitted to Canterbury.[19]

After travelling to Rome to receive his pallium, the symbol of his authority as an archbishop, William discovered that Thurstan had arrived before him, and had presented a case against William's election to Pope Callixtus II.[1] There were four objections to William's election: first that he was elected in the king's court; second that the chapter of Canterbury had been coerced and was unwilling; third that his consecration was unlawful because it was not performed by Thurstan; and fourth that a monk should be elected to the See of Canterbury, which had been founded by Augustine of Canterbury, a monk.[7] However, King Henry I and the Emperor Henry V, Henry I's son-in-law, persuaded the pope to overlook the irregularities of the election, with the proviso that William swore to obey "all things that the Pope imposed upon him".[12][20] At the conclusion of the visit the pope denied the primacy of Canterbury over York, dismissing the Canterbury cathedral chapter's supposed papal documents as forgeries.[7] The outcome was in accordance with most earlier papal rulings on the primacy issue, which involved not taking sides and thus reinforcing papal supremacy. William returned to England, and was enthroned at Canterbury on 22 July 1123.[1]

The archbishop's next opponent was the papal legate of the new Pope Honorius II, Cardinal John of Crema,[20] who arrived in England in 1125. A compromise between York and Canterbury was negotiated, which involved Canterbury allowing York the supervision of the dioceses of Bangor, Chester, and St Asaph in return for Thurstan's verbal submission and the written submission of his successors. The pope, however, rejected the agreement, likely because he wished to preserve his own primacy, and substituted his own resolution.[1] The papal solution was that Honorius would appoint William papal legate in England and Scotland, which was done in 1126,[21] giving William the position over York, but it was dependent on the will of the pope, and would lapse on the pope's death. The arrangement merely postponed the problem however, as neither Thurstan nor William renounced their claims. That Christmas, at a royal court, Thurstan unsuccessfully attempted to claim the right to ceremonially crown the king as well as have his episcopal cross carried before him in Canterbury's province.[1] As a result of his lengthy dispute with Thurstan, William travelled to Rome more frequently than any bishop before him except for Wilfrid in the 7th century.[22]

Archiepiscopal activities

Legatine councils in 1125, 1127 and 1129 were held in Westminster, the last two called by Archbishop William.[1] The council of 1125 met under the direction of John of Crema and prohibited simony, purchase of the sacraments, and the inheritance of clerical benefices.[23] John of Crema had been sent to England to seek a compromise in the Canterbury–York dispute, but also to publicise the decrees of the First Council of the Lateran held in 1123, which neither William nor Thurstan had attended. Included in canons were the rejection of hereditary claims to a benefice or prebend, which was a source of consternation to the clergy. Also prohibited was the presence of any women in clergy's households unless they were relatives.[1] In 1127 the council condemned the purchase of benefices, priesthoods, or places in monastic houses.[24] It also enacted canons declaring that clergy who refused to give up their wives or concubines would be deprived of their benefices, and that any such women who did not leave the parish where they had been could be expelled and even forced into slavery.[1] Lastly, in 1129 the clergy were once more admonished to live a celibate life and to put aside their wives.[23] This council was presided over by King Henry, who then undermined the force of the prohibition of concubines by permitting the clergy to pay a fine to the royal treasury to keep their women. William's allowance of this royal fine was condemned by the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon.[1] The festival of the Conception was also allowed at one of these councils.[24]

As well as the councils, William was active in his diocese, and was interested in reforming the churches in his diocese. A conflict with Alexander of Lincoln over a church in Alexander's diocese led to further condemnation by Henry of Huntingdon[1] and prompted Henry to write that "no one can sing [William's] praises because there's nothing to sing about."[25] William seems to have been somewhat eclipsed in ecclesiastical administration and appointments by Roger of Salisbury, Bishop of Salisbury, and King Henry's primary advisor.[26] William reformed the nunnery of Minster-in-Sheppey however, and he installed a college of regular canons at the church of St. Gregory's, in Canterbury. He also secured a profession of obedience from the newly installed abbot of St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury.[1] His legateship from Honorius lapsed when the pope died in February 1130, but it was renewed by Honorius' successor Pope Innocent II in 1132.[13]

During William's last years he attempted to reform St Martin's, Dover. The king had granted the church to the archbishop and the diocese of Canterbury in 1130, and William had a new church building constructed near Dover. The archbishop had planned to install canons regular into the church, and on William's deathbed dispatched a party of canons from Merton Priory to take over St Martin's. However, the party of canons, who had been accompanied by two bishops and some other clergy, were prevented from entering by a monk of Canterbury Cathedral, who claimed that St Martin's belonged to the monks of the cathedral chapter. The canons from Merton did not press the issue in the face of the Canterbury chapter's appeal to Rome, and after William's death, the cathedral chapter sent 12 monks to St Martin's instead.[1]

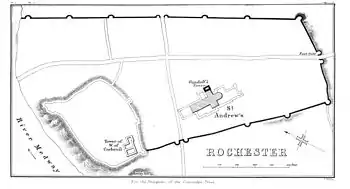

The construction of the keep of Rochester Castle—at 115 feet (35 m), the tallest Norman-built keep in England—was initiated at William's orders.[27] Built for King Henry, it is still intact, although it no longer has a roof or floors. The work at Rochester was built within the stone curtain walls that Gundulf of Rochester had erected in the late 11th century. The keep was designed for defence and also to provide comfortable living quarters, which were probably intended for use by the archbishops when they visited Rochester.[28] In 1127, the custody of Rochester Castle was granted to William and his successors as archbishop by King Henry, including the right to fortify the place as the archbishops wished, and the right to garrison the castle with their own men.[29] In the view of the historian Judith Green, the grant of the castle was partly to secure the loyalty of the archbishop to the king, and partly to help secure the defences of the Kent coast.[30] William also completed the construction of Canterbury Cathedral, which was dedicated in May 1130.[1]

Final years

The archbishop swore to Henry I that he would support Henry's daughter Matilda's claim to the English throne,[21] but after Henry's death he instead crowned Stephen, on 22 December 1135. He was persuaded to do so by Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester and Stephen's brother,[31][32] and Roger of Salisbury, Bishop of Salisbury. The bishops argued that Henry had no right to impose the oath, and that the dying king had released the barons and the bishops from the oath in any event. The royal steward, Hugh Bigod, swore he had been present at the king's deathbed and had heard the king say that he released the oath.[33]

William did not long outlive Henry, dying at Canterbury on 21 November 1136.[14] He was buried in the north transept of Canterbury Cathedral.[1] Contemporaries were grudging in their praise, and William's reputation suffered after the accession of Matilda's son, Henry II, to the English throne. William of Malmesbury said that William was a courteous and sober man, with little of the flamboyant lifestyle of the more "modern" bishops. The author of the Gesta Stephani claimed that William was avaricious and hoarded money. None of the chroniclers doubted his piety, even when they named him a perjurer and a traitor for his coronation of Stephen.[1]

Notes

- This would have included the barons and earls as well as the leading royal servants on the secular side, and the bishops and some of the abbots on the ecclesiastical side.[1]

Citations

- Barlow "Corbeil, William de" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Hollister Henry I p. 23

- Hollister Henry I p. 432

- Spear "Norman Empire" Journal of British Studies p. 6

- Bethell "William of Corbeil" Journal of Ecclesiastical History pp. 145–146

- Bethell "William of Corbeil" Journal of Ecclesiastical History p. 146

- Bethell "English Black Monks" English Historical Review

- Knowles, et al. Heads of Religious Houses p. 173

- Knowles, et al. Heads of Religious Houses p. 183

- Barlow English Church p. 85

- Cantor Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture p. 282

- Hollister Henry I pp. 288–289

- Greenway "Canterbury: Archbishops" Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces)

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 232

- Green Henry I pp. 178–179

- Knowles Monastic Order p. 175

- Quoted in Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings p. 399

- Barlow English Church pp. 39–44

- Burton "Thurstan" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- quoted in Cantor Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture pp. 312–313

- Barlow English Church pp. 44–45

- Bethell "William of Corbeil" Journal of Ecclesiastical History pp. 157–158

- Cantor Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture pp. 275–276

- Barlow English Church p. 195

- Quoted in Barlow "Corbeil, William de" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Cantor Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture p. 299

- Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings p. 277

- Platt Castle in Medieval England & Wales pp. 23–24

- DuBoulay Lordship of Canterbury p. 80

- Green Henry I p. 270

- Huscroft Ruling England p. 72

- Hollister Henry I pp. 478–479

- Crouch Normans p. 247

References

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Barlow, Frank (2004). "Corbeil, William de (d. 1136)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6284. Retrieved 8 November 2007. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Bartlett, Robert C. (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075–1225. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822741-8.

- Bethell, D. L. (October 1969). "English Black Monks and Episcopal Elections in the 1120s". The English Historical Review. 84 (333): 673–694. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIV.CCCXXXIII.673. JSTOR 563416.

- Bethell, Denis (October 1968). "William of Corbeil and the Canterbury-York Dispute". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 19 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1017/S0022046900056864. S2CID 162617876.

- Burton, Janet (2004). "Thurstan (c. 1070–1140)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27411. Retrieved 30 August 2010. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cantor, Norman F. (1958). Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture in England 1089–1135. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 186158828.

- Crouch, David (2007). The Normans: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 978-1-85285-595-6.

- DuBoulay, F. R. H. (1966). The Lordship of Canterbury: An Essay on Medieval Society. New York: Barnes & Noble. OCLC 310997.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Green, Judith A. (2006). Henry I: King of England and Duke of Normandy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74452-2.

- Greenway, Diana E. (1991). "Canterbury: Archbishops". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300. Vol. 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces). Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2001). Frost, Amanda Clark (ed.). Henry I. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08858-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (1999). Domesday Descendants: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166: Pipe Rolls to Cartae Baronum. Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-863-3.

- Knowles, David; London, Vera C. M.; Brooke, Christopher (2001). The Heads of Religious Houses, England and Wales, 940–1216 (Second ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80452-3.

- Knowles, David (1976). The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940–1216 (Second reprint ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05479-6.

- Platt, Colin (1996). The Castle in Medieval England & Wales (Reprint ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0-7607-0054-0.

- Spear, David S. (Spring 1982). "The Norman Empire and the Secular Clergy, 1066-1204". Journal of British Studies. XXI (2): 1–10. doi:10.1086/385787. JSTOR 175531. S2CID 153511298.