Williams and Walker Co.

George Walker and Bert Williams were two of the most renowned figures of the minstrel era. However the two did not start their careers together. Walker was born in 1873 in Lawrence, Kansas.[2] His onstage career began at an early age as he toured in black minstrel shows as a child. George Walker became a better known stage performer as he toured the country with a traveling group of minstrels. George Walker was a "dandy", a performer notorious for performing without makeup due to his dark skin.[2] Most vaudeville actors were white at this time and often wore blackface. As Walker and his group traveled the country, Bert Williams was touring with his group, named Martin and Selig's Mastodon Minstrels.[3] While performing with the Minstrels, African American song-and-dance man George Walker and Bert Williams met in San Francisco in 1893. George Walker married Ada Overton in 1899. Ada Overton Walker was known as one of the first professional African American choreographers. Prior to starring in performances with Walker and Williams, Overton wowed audiences across the country for her 1900 musical performance in the show Son of Ham.[4] After falling ill during the tour of Bandana Land in 1909, George Walker returned to Lawrence, Kansas where he died on January 8, 1911. He was 38.[2]

Bert Williams was born on November 12, 1874, in Nassau, Bahamas and later moved to Riverside, California. Williams began his performance career in 1886 when he joined Lew Johnson's Minstrels.[5] In 1893,while he was still a teenager, Williams joined Martin and Selig's Mastodon Minstrels. Bert Williams had very fair skin for an African-American man which allowed him easier access to the white dominated vaudeville scene. George Walker and Bert Williams performed many song and dance numbers, comedic skits as well as comedic songs. The twosome debuted in New York at the Casino Theatre in 1898. Their act, "The Gold Bug" consisted of songs, dance that focused on Walker trying to convince Williams to join him in get-rich-quick schemes. Later in life Williams went on to a solo career and then worked for a company called the Ziegfeld Follies. On February 21, 1922, Williams collapsed on stage while performing and later returned to New York City. He died a month later on March 4, 1922.[3]

"Two Real Coons"

The duo called themselves the "Two Real Coons" as most of the talent in vaudeville were primarily white and were painted in blackface.[2] At first the lighter-skinned Bert Williams would trick the darker Walker in their skits, but after a while the two noticed the crowd reacted better when the two reversed roles. Williams donned the burnt cork black face while George Walker, the "dandy" performed without any makeup at all. Blackface was said to work as a double mask for Williams as it emphasized that he was different from vaudevillians and white audiences. Williams played the role of the comic figure in blackface while George Walker played the straight man, an obvious counter to the dominant negative stereotypes of the time. While performing their vaudeville act throughout the United States, the "Two Real Coons" headlined at the Koster and Bial's vaudeville house where they popularized the cakewalk, a dance competition in which the winning couple was rewarded with a cake.[2][3]

Offstage life

Offstage life was different for the two men. Both men faced extreme racism. Racial prejudice was said to have shaped Bert William's career as he based his humor on universal situations in which it was possible that one of the audience member would find themselves. Often, white vaudevillians would refuse to appear on the same playbill as Williams, and it is said that others complained that his material was better than theirs. As a comedian and songwriter he was loved by all, however he often faced racism even by the restaurants and hotels that he played for. Williams was forced to perform in blackface makeup, gloves and other attire as he consistently played out stereotypical black characters. After Williams’ death on March 4, 1922, the Chicago Defender stated that "No other performer in the history of the American stage enjoyed the popularity and esteem of all races and classes of theater-goers to the remarkable extent gained by Bert Williams."[3] George Walker fought against racism as he provided a place within the company for colored artists which enabled an African American presence on stages across the country. George Walker was an esteemed businessman who was in charge of managing the affairs of the Walker and Williams Company. A company that brought them and those that worked for them fame and wealth both nationally and internationally.[2]

Williams and Walker Company Productions

In 1903, they performed "In Dahomey" an elaborate play at Buckingham Palace in London. This was "the first full length musical written and played by blacks to be performed at a major Broadway house". The play contained original music, props, and scenery. George Walker played a hustler disguised as a prince from Dahomey who was sent by a group of deceitful investors to convince blacks to join a colony.[2] Other Williams and Walker Company productions include: The Sons of Ham (1900), The Policy Players (1899), and Bandana Land (1908).

Williams and Walker, together with eight other members of their vaudeville troupe were Initiated into Scottish Freemasonry on 2 May, Passed on 16 May and Raised on 1 June 1904.

The Scottish Lodge concerned was Lodge Waverley, No.597, which continues to meet in Edinburgh

1) Egbert Austin Williams Aged 30

2) George William Walker Aged 31

3) Henry Troy Aged 28

4) John Edwards Aged 26

5) George Catlin Aged 37

6) Peter Hampton Aged 33

7) Green Henri Tapley Aged 29

8) John Leubrie Hill [Hul?] Aged 30

9) James Escort Lightfoot Aged 33

10) Alexander Rogers Aged 28

All are recorded as being 'Theatrical Professionals'.[6]

Works cited

Bordman, Gerald. Musical Theatre: A Chronicle (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 190. Print.

Campbell, Brent."Walker, George (1873-1911) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed." Walker, George (1873-1911) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. BlackPast.org, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2015.

Chude-Sokei, Louis Onuorah. The Last "darky": Bert Williams, Black-on-black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora. Durham: Duke UP, 2006. Print.

Forbes, Camille F., Aug 01, 2008, Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America's First Black Star Basic Books, New York

Gale Research. "Bert Williams." PBS. PBS, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2015.

James Haskins, Black Theater in America (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1982)

Mitchell, Loften. Black Drama; the Story of the American Negro in the Theatre. New York: Hawthorn,1967. Print.

Woll, Allen L. Black Musical Theatre: From Coontown to Dreamgirls. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1989. Print.

https://ia801600.us.archive.org/BookReader/BookReaderImages.php?zip=/20/items/jstor-20542241/20542241_jp2.zip&file=20542241_jp2/20542241_0001.jp2&scale=8&rotate=0Walker

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ImAJohnahManWilliamsWalkerCover.jpeg

Thorne, Wells. "The Later Years of Aida Overton Walker; 1911–1914." Black Acts: Creativity and Celebrity in Twentieth-Century Theater. N.p., n.d. Web. 3 Oct. 2016. <http://blackacts.commons.yale.edu/exhibits/show/blackacts/walker>.

See also

Daisy Tapley Contralto, member of the company,-In Dahomey w.-Henri Green Tapley.

References

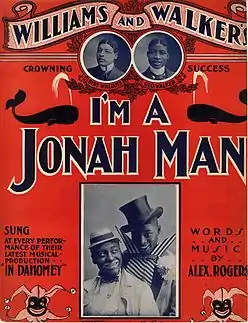

- Rogers, Alex (1903-01-01), "I'm a Jonah Man" from the musical "In Dahomey". 1903 sheet music cover. Bert Williams and George Walker, vaudeville stars "Williams & Walker", shown on cover in both formal portraits and in stage costumes with blackface., retrieved 2016-10-03

- "Walker, George (1873-1911) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- "Bert Williams | The Stars | Broadway: The American Musical | PBS". Broadway: The American Musical. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- Thorne, Wells. "The Later Years of Aida Overton Walker; 1911–1914". Black Acts. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- "Bert Williams". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- "The Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2020-06-21.