Winchester syndrome

Winchester syndrome is a rare hereditary connective tissue disease described in 1969,[3] of which the main characteristics are short stature, marked contractures of joints, opacities in the cornea, coarse facial features, dissolution of the carpal and tarsal bones (in the hands and feet, respectively), and osteoporosis. Winchester syndrome was once considered to be related to a similar condition, multicentric osteolysis, nodulosis, and arthropathy (MONA).[4][5] However, it was discovered that the two are caused by mutations found in different genes; however they mostly produce the same phenotype or clinical picture.[4] Appearances resemble rheumatoid arthritis. Increased uronic acid is demonstrated in cultured fibroblasts from the skin and to a lesser degree in both parents. Despite initial tests not showing increased mucopolysaccharide excretion, the disease was regarded as a mucopolysaccharidosis.[3] Winchester syndrome is thought to be inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.

| Winchester syndrome or Torg-Winchester syndrome or Multicentric Osteolysis, Nodulosis, and Arthropathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Torg-Winchester syndrome[1] Multicentric Osteolysis, Nodulosis, and Arthropathy[2] |

| |

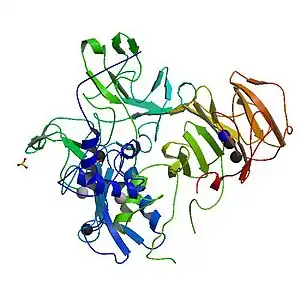

| Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 | |

Symptoms

Symptoms of Winchester or MONA syndrome begin with the deterioration of bone within the hands and feet. This loss of bone causes pain, pathological fractures and limited mobility. The abnormalities of the bone spread to other areas of the body, mostly the joints. This causes arthropathy: stiffening of the joints (contractures) and swollen joints. Many people develop osteopenia and osteoporosis throughout their entire body. The bone and joint manifestations characteristically start in the hands and feet then spread to the larger joints eventually like elbows and shoulders in the upper extremities and knees and hips in the lower extremities. Due to the damage to the bones, many affected individuals suffer from bone fractures, arthritis and occasionally short stature.[4] [6][7]

Many individuals experience leathery skin where the skin appears dark and thick. Excessive hair growth is known to be found in these darker areas of the skin (hypertrichosis). The eyes may develop a white or clear covering the cornea (corneal opacities) which can cause problems with vision.[5]

Mechanism

Winchester syndrome is believed to be inherited through autosomal recessive inheritance.[8][4] It believed that this disease is caused by a nonlysosomal connective-tissue disturbance. The protein inactivation mutation is found on the matrix metalloproteinase 2 gene (MMP2).[4] [9] MM2 is responsible for bone remodeling. Bone remodeling is the process in which old bone is destroyed so that new bone can be created to replace it. This mutation causes a multicentric osteolysis and arthritis syndrome. It is hypothesized that the loss of an upstream MMP-2 protein activator MT1-MMP, results in decreased MMP-2 activity without affecting MMP2. The inactivating homoallelic mutation of MT1-MMP can be seen at the surface of fibroblasts. It was determined that fibroblasts lacking MT1-MMP lack the ability to degrade type I collagen which leads to anomalous function.[9]

Diagnosis

In 1989, a set of diagnostic criteria were created for the diagnosing of Winchester syndrome.[10] The typical diagnosis criteria begin with skeletal radiological test results and two of the defining symptoms, such as short stature, coarse facial features, hyperpigmentation, or excessive hair growth.[10] The typical tests that are performed are x-ray and magnetic resonance imaging. A complete skeletal radiographic survey is mandatory for diagnosis of Winchester or MONA syndrome together with a detailed musculoskeletal examination and craniofacial morphology assessment.[4] It appears that Winchester syndrome is more common in women than men.[6] Winchester syndrome is very rare. There have only been a few individuals worldwide who were reported to have this disorder.[5]

Treatment

There is no known cure for Winchester syndrome; however, there are many therapies that can aid in the treatment of symptoms.[6] Such treatments can include medications: anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants, and antibiotics. Many individuals will require physical therapy to promote movement and use of the limbs affected by the syndrome. Bisphosphonates have been used to improve bone quality and density or at least halt the progression of bone damages or osteolysis.[11] Genetic counseling is typically prescribed for families to help aid in the understanding of the disease. There are a few clinical trials available to participate in. The prognosis for patients diagnosed with Winchester syndrome is positive. It has been reported that several affected individuals have lived to middle age; however, the disease is progressive and mobility will become limited towards the end of life. Eventually, the contractures will remain even with medical intervention, such as surgery.[6]

Research

In 2005, a patient with Winchester syndrome was shown to have mutations in the matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) gene.[12] A 2006 study showed other mutations found in the MMP2 gene. This has led to the belief that there are many similar diseases within this family of mutations.[13] As of 2007, it was found that these mutations are also found in Torg and Nodulosis-arthropathy-osteolysis syndrome (NAO). This means that Torg, NAO, and Winchester syndrome are allelic disorders.[4] [12] In 2014, a new case of Winchester syndrome was reported.[14] According to a recently published article, it was discovered that multicentric osteolysis, nodulosis, and arthropathy (MONA) and Winchester syndrome are different diseases. Mutations in MMPS and MT1-MMP result in similar but distinctly different "vanishing bone" syndromes.[8]

References

- RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Torg Winchester syndrome". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "OMIM Entry - # 259600 - MULTICENTRIC OSTEOLYSIS, NODULOSIS, AND ARTHROPATHY; MONA". omim.org.

- Winchester P, Grossman H, Lim WN, Danes BS (May 1969). "A new acid mucopolysaccharidosis with skeletal deformities simulating rheumatoid arthritis". Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 106 (1): 121–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.106.1.121. PMID 4238825.

- Elsebaie H, Mansour MA, Elsayed SM, Mahmoud S, El-Sobky TA (December 2021). "Multicentric Osteolysis, Nodulosis, and Arthropathy in two unrelated children with matrix metalloproteinase 2 variants: Genetic-skeletal correlations". Bone Rep. 15: 101106. doi:10.1016/j.bonr.2021.101106. ISSN 2352-1872. PMC 8283316. PMID 34307793.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "Winchester syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- "Winchester Syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- "Torg Winchester syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Evans BR, Mosig RA, Lobl M, Martignetti CR, Camacho C, Grum-Tokars V, Glucksman MJ, Martignetti JA (September 2012). "Mutation of membrane type-1 metalloproteinase, MT1-MMP, causes the multicentric osteolysis and arthritis disease Winchester syndrome". Am J Hum Genet. 91 (3): 572–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.07.022. PMC 3512002. PMID 22922033.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "MMP14 gene". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- "Winchester Syndrome Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination, Causes". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Pichler K, Karall D, Kotzot D, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Rümmele-Waibel A, Mittaz-Crettol L, Wanschitz J, Bonafé L, Maurer K, Superti-Furga A, Scholl-Bürgi S (September 2016). "Bisphosphonates in multicentric osteolysis, nodulosis and arthropathy (MONA) spectrum disorder - an alternative therapeutic approach". Sci Rep. 6: 34017. Bibcode:2016NatSR...634017P. doi:10.1038/srep34017. PMC 5043187. PMID 27687687.

- Zankl A, Bonafé L, Calcaterra V, Di Rocco M, Superti-Furga A (March 2005). "Winchester syndrome caused by a homozygous mutation affecting the active site of matrix metalloproteinase 2". Clin Genet. 67 (3): 261–6. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00402.x. PMID 15691365. S2CID 29033013.

- Rouzier C, Vanatka R, Bannwarth S, Philip N, Coussement A, Paquis-Flucklinger V, Lambert JC (March 2006). "A novel homozygous MMP2 mutation in a family with Winchester syndrome". Clin Genet. 69 (3): 271–6. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00584.x. PMID 16542393. S2CID 46503028.

- Ekbote AV, Danda S, Zankl A, Mandal K, Maguire T, Ungerer K (2014). "Patient with mutation in the matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) gene - a case report and review of the literature". J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 6 (1): 40–6. doi:10.4274/Jcrpe.1166. PMC 3986738. PMID 24637309.