Woiwurrung

The Woiwurrung, also spelt Woi-wurrung, Woi Wurrung, Woiwurrong, Woiworung, Wuywurung, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Woiwurrung language group, in the Kulin alliance.

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Woiwurrung language, English | |

| Religion | |

| Australian Aboriginal mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Boonwurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung, Wathaurong see List of Indigenous Australian group names |

The Woiwurrung people's territory in Central Victoria extended from north of the Great Dividing Range, east to Mount Baw Baw, south to Mordialloc Creek and to Mount Macedon, Sunbury and Gisborne in the west. Their lands bordered the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east in Gippsland, the Boon wurrung people to the south on the Mornington Peninsula, and the Dja Dja Wurrung and Taungurung to the north.

Before colonisation, they lived predominantly as aquaculturists, swidden agriculturists (growing grasslands by fire-stick farming to create fenceless herbivore grazing,[1] garden-farming murnong yam roots and various tuber lilies as major forms of starch and carbohydrates[2]), and hunters and gatherers. Seasonal changes in the weather, availability of foods and other factors would determine where campsites were located, many near the Birrarung and its tributaries.

Each of the various Woiwurrung tribes had its own distinct territory and boundary usually determined by waterways. The clans included:

- The Wurrundjeri-Willam, who occupied the Yarra River and its tributaries and inhabited the area now covered by the city of Melbourne. Referred to initially by Europeans as the Yarra tribe.

- The Marin-Bulluk

- The Kurung Jang Balluk

- The Wurundjeri Balluk

- The Balluk Willam

- The Gunung Willam Balluk

- The Talling Willam

The term Wurundjeri has become one of the common terms used today for descendants of all the Woiwurrung tribes, as they were forced together for the survival of their ethnic group. Their totems are Bundjil the eagle and Waang the crow.

History

Pre-history

Wurundjeri is a common recent name for people who have lived in the Woiwurrung area for up to 40,000 years, according to Gary Presland.[lower-alpha 1] They lived by fishing, hunting and gathering, and made a good living from the rich food sources of Port Phillip both before and after its flooding about 7,000–10,000 years ago, and the surrounding grasslands.[3]

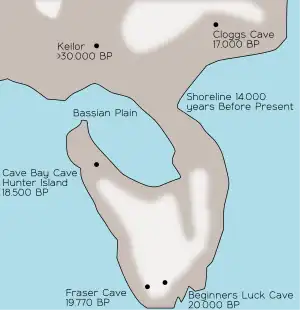

At the Keilor Archaeological Site a human hearth excavated in 1971 was radiocarbon-dated to about 31,000 years BP, making Keilor one of the earliest sites of human habitation in Australia.[4] A cranium found at the site has been dated at between 12,000[5] and 14,700 years BP.[4]

Archaeological sites in Tasmania and on the Bass Strait Islands have been dated to between 20,000 – 35,000 years ago, when sea levels were 130 metres below present level allowing Aboriginal people to move across the region of southern Victoria and on to the land bridge of the Bassian plain to Tasmania by at least 35,000 years ago.[6][7]

During the Ice Age about 20,000 years BP, the area now known as Port Phillip would have been dry land, and the Yarra and Werribee river would have joined to flow through the heads then south and south west through the Bassian plain before meeting the ocean to the west. Tasmania and the Bass Strait islands became separated from mainland Australia around 12,000 BP, when the sea level was approximately 50m below present levels.[6] Port Phillip was flooded by post-glacial rising sea levels between 8,000 and 6,000 years ago.[6]

Oral history and creation stories from the Wathaurong, Woiwurrung and Boon wurrung languages describe the flooding of the bay. Hobsons Bay was once a kangaroo hunting ground. Creation stories describe how Bunjil was responsible for the formation of the bay,[8] or the bay was flooded when the Yarra river was created (Yarra Creation Story[9]).

First contact with non-Aboriginal peoples

.gif)

The Woiwurrung tribes would have been aware of the Europeans, through the close relationship to the Boon wurrung people of the coast who came into contact with the Baudin expedition on the French ship Naturaliste during 1801, and then the British settlement at Sullivan Bay in 1803, near modern-day Sorrento, Victoria. William Buckley, a convict, escaped from this abortive settlement and lived for more than 30 years with the Wathaurong people before approaching John Batman's party in 1835. He told George Langhorne in 1836:

I frequently entertained them (the Wada wurrung), when sitting around the campfires, with accounts of the English People, Houses, Ships – great guns etc. to which accounts they would listen with great attention – and express much astonishment.[10]

The Boon wurrung people, living primarily along the Port Philip and Western Port coast, were also subjected to raids on their camps by sealers from at least 1809 to as late as 1833, which were frequently violent with men being killed and the women being abducted and enslaved by sealers for sexual partners and taken to the Islands in Bass Strait where the sealers had their camps.[7] This would have impacted the economic and social ties binding the Woiwurrung and Boon wurrung peoples.

James Fleming, one of the party of Charles Grimes in HMS Cumberland who explored the Maribyrnong River and the Yarra River as far as Dights Falls in February 1803 reported smallpox scars on several Aboriginal people he met, indicating that a smallpox epidemic had swept through the tribes around Port Philip before 1803 reducing the population.[11] Broome puts forward that two epidemics of smallpox almost annihilated the Kulin tribes by perhaps killing half each time in the 1790s and again around 1830.[12] The Wurundjeri incorporated these epidemics in their oral tradition as the Mindi, a rainbow serpent from the Northwest sent to destroy or afflict any people for bad deeds, hissing and spreading white particles from its mouth from which disease could be inhaled.

Any plague is supposed to be brought on by the Mindye or some of its little ones. I have no doubt that, in generations gone by, there has been an awful plague of cholera or black fever, and that the wind at the time, or some other appearance from the north-west has given rise to this strange being.[13]

Treaty

On 6 June 1835 John Batman met with eight elders of the Woiwurrung people including Bebejan and Billibellary, the traditional owners of the lands around the Yarra River. The meeting took place on the bank of a small stream, likely to be the Merri Creek and treaty documents were signed along with exchanges of goods by both sides.[14] For a purchase price including tomahawks, knives, scissors, flannel jackets, red shirts and a yearly tribute of similar items, Batman obtained about 200,000 hectares (2,000 km2) around the Yarra River and Corio Bay. The total value of the goods has been estimated at about £100 in the value of the day.[15] In return the Woiwurrung offered woven baskets of examples of their weaponry and two Possum-skin cloaks, a highly treasured item. After the treaty signing, a celebration took place with the Parramatta Aborigines with Batman's party dancing a corroboree.[16]

The treaty was significant as it was the first and only documented time when European settlers negotiated their presence and occupation of Aboriginal lands.[17] The Treaty was immediately repudiated by the colonial government in Sydney. The 1835 proclamation by Governor Richard Bourke implemented the doctrine of terra nullius upon which British settlement was based, reinforcing the concept that there was no land owner before British possession and that Aboriginal people could not sell or assign the land, and individuals could only acquire it through distribution by the Crown.[18]

Dispossession and conflict

Derrimut, an arweet of the Boon wurrung informed the early European settlers in October 1835 of an impending attack by "up-country people". The colonists armed themselves, and the attack was averted. Benbow from the Boon wurrung and Billibellary, from the Wurundjeri, also acted to protect the colonists in what is perceived as part of their duty of hospitality.[19]

In 1840, conflict erupted at the Battle of Yering, near present-day Yarra Glen, in which Border Police under the direction of Commissioner of Lands, Captain Henry Gisborne captured Wurundjeri leader Jaga Jaga, eliciting a violent confrontation involving 50 Wurundjeri clansmen where shots were exchanged.[20][21]

As early as 1843 Billibellary requested land for the Wurundjeri to settle. In August 1850 it is likely that the Woiwurrung requested land at Bulleen, but William Thomas, a Protector of Aborigines in Victoria, rejected their request as being too close to white settlement. In 1852 the Woiworrung gained 782 hectares along the Yarra at Warrandyte, while the Boon wurrung were allocated 340 hectares at Mordialloc Creek. These reserves were never staffed by whites and were not permanent camps, but acted as distribution depots where rations and blankets were distributed, with the intention being to keep the tribes away from the growing settlement of Melbourne.[22] The Aboriginal Protection Board revoked these two reserves in 1862 and 1863, considering them then too close to Melbourne.[23]

Social impact

The Woiwurrung and Boon Wurrong people bore the brunt of the effects of British settlement in the Foundation of Melbourne from 1835 onwards, with the population declining rapidly. In the 27 years following the foundation of Melbourne, the population of Woiworung and Boon wurrung language groups was reduced from 207 to 28 people. Many people were killed by diseases, including venereal disease, introduced by the Europeans. The birth rate also drastically declined for Woiwurrung and Boon wurrung with only five births between 1838 and 1848, while there were 52 deaths for the same period.[24] William Thomas remarked in 1844 that "Infanticide I am persuaded is most awfully on the increase though it cannot be detected—their argument has some reason 'No good pickaninnys now no country'".[lower-alpha 2][25]

Native Police Corps

On the instructions of Charles La Trobe a Native Police Corps was established and underwritten by the government in 1842 in the hope of civilising the Aboriginal men. It was based at Narre Warren, but later moved to Merri Creek and continued in operation until disbanded in January 1853. As senior Wurundjeri elder, Billibellary's cooperation for the proposal was important for its success, and after deliberation he backed the initiative and even proposed himself for enlistment, but resigned after about a year when he found that it was to be used to capture and even kill other natives. He did his best from then to undermine the Corps and as a result many native troopers deserted and few remained longer than three or four years. Participation in the police corps failed to stop troopers participating in tribal ceremonies, gatherings and rituals.[26][27]

Coranderrk

In 1863 the surviving members of the Woiwurrung tribes and speakers were given "permissive occupancy" of Coranderrk Station, near Healesville and forcibly resettled. Despite numerous petitions, letters, and delegations to the Colonial and Federal Government, the grant of this land in compensation for the country lost was refused. Coranderrk was closed in 1924 and its occupants bar five refusing to leave Country were again moved to Lake Tyers in Gippsland.

Structure, borders and land use

Communities consisted of six or more (depending on the extent of the territory) land-owning groups called clans that spoke a related language and were connected through cultural and mutual interests, totems, trading initiatives and marriage ties. Access to land and resources, such as the Birrarung, by other clans, was sometimes restricted depending on the state of the resource in question. For example; if a river or creek had been fished regularly throughout the fishing season and fish supplies were down, fishing was limited or stopped entirely by the clan who owned that resource until fish were given a chance to recover. During this time other resources were utilised for food. This ensured the sustained use of the resources available to them. As with most other Kulin territories, penalties such as spearings were enforced upon trespassers. Today, traditional clan locations, language groups and borders are no longer in use and descendants of Woiwurrung Tribes including the Wurundjeri tribe people live within modern day society.

Tribes / Clans

It is generally considered that before European settlement, six separate clans existed:

- Wurundjeri-balluk & Wurundjeri-willam: Yarra Valley, Yarra River catchment area to Heidelberg

- Bulluk-willam: south of the Yarra Valley extending down to Dandenong, Cranbourne, Koo-wee-rup Swamp

- Gunnung-willam-balluk: east of the Great Dividing Ranges and north to Lancefield

- Kurung-jang-balluk: Melton to Werribee River to Sunbury

- Marin-balluk (Boi-berrit): land west of the Maribyrnong River, Sunshine and Sunbury

- Kurnaje-berreing: the land between the Maribyrnong and Yarra Rivers

Diplomacy

When foreign people passed through or were invited onto Woiwurrung lands the ceremony of Tanderrum – freedom of the bush – would be performed. This allowed safe passage and temporary access and use of land and resources by foreign people. It was a diplomatic rite involving the landholder's hospitality and a ritual exchange of gifts.

Language

The Wurundjeri people were part of the Woiwurrung language group; each clan spoke a slight variation of the Woiwurrung language. Some basic terms include;

- bulluk, balluk: swamp

- nira: cave

- willam, wilam, illam, yilam: hut, camp, bark

- gunung, gunnung: river

- ngamudji: red colours during sunset, white man

- The Jindyworobak Movement claim to have taken their name from a Woiwurrung phrase jindi worobak meaning to annex or join.

Religion

The Woiwurrung people shared the same belief system as other Kulin nation territories, based on a creative epoch known as the Dreamtime which stretches back into a remote era in history when the creator ancestors known as the First Peoples travelled across the land, creating and naming as they went. Indigenous Australia's oral tradition and religious values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in this Dreamtime. The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with their own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. The two moiety totems of the Woiwurrung people are Bunjil the Eaglehawk and Waang the Crow.

Dreamtime stories

Recreation

William Thomas witnessed Woiwurrung people playing the game of Marn grook in 1841, according to Robert Brough-Smyth, in The Aborigines of Victoria (1878):

The men and boys joyfully assemble when this game is to be played. One makes a ball of possum skin, somewhat elastic, but firm and strong. The players of this game do not throw the ball as a white man might do, but drop it and at the same time kicks it with his foot. The tallest men have the best chances in this game. Some of them will leap as high as five feet from the ground to catch the ball. The person who secures the ball kicks it. This continues for hours and the natives never seem to tire of the exercise.

The game was a favourite of the Woiwurrung clans and two teams were sometimes based on the traditional totemic moieties of Bunjil (eagle) and Waang (crow) of the Kulin people. Robert Brough-Smyth saw the game played at Coranderrk Mission Station, where ngurungaeta William Barak discouraged the playing of imported games like cricket and encouraged the traditional native game of marn grook.[28] There is some debate about whether the game influenced or was the origin of Australian Rules Football.[29]

As late as 1862 the Woiwurrung Aboriginal people were "often seen in their possum skin coats, armed with spears, and retreating mainly to the unsold hill north of Collingwood where they camped with their dogs, played football with a possum-skin ball and fought with other Aborigines", according to researchers McFarlane and Roberts, reported on in the Herald Sun.[30]

Places of significance

There are a number of significant sites, in particular those found near the Yarra & Maribyrnong Rivers and the Merri Creek where corroborees were held between clans and perhaps neighbouring territories to share in music and dance, exchange news and trade. Other places of significance for the Wurundjeri people include:

- Kings domain Resting Place: In 1985 the remains of 38 Victorian Aboriginal people held by the Museum Victoria, including Woiwurrung people, were reburied here.[31]

- Queen Victoria Market: burial site for many Aboriginal people as well as European settlers.[32]

- Corner Franklin and Bowen streets: First public executions took place in Melbourne on 20 January 1842, of two Tasmanian Aborigines: Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, who had conducted a successful guerilla style resistance campaign around Western Port.[33][34]

- Jolimont: gatherings of Kulin territories around the site of the MCG and Yarra Park. See also Fitzroy Gardens Scarred tree.[35]

- Bundoora Park: extensively used for bark and quarrying silcrete, fifteen archeological sites in the area.[36]

- Burnley Park Corroboree Tree...[37]

- Fawkner Park: favourite camping ground.[38]

- Bolin Bolin Billabong in Bulleen: location of sacred and social interaction between clans.[39]

- Gellibrand Hill and Moonee Ponds Creek Valley. A 1991 archeological survey located 31 sites, including camping grounds, silcrete outcrops and scarred trees.[40]

- Birrarung: the primary river flowing through the territory, a major food source and meeting place...[41]

- Warrandyte: a gorge in the middle reaches of the Birrarung, named for the actions of the dreamtime figure "Bunjil"

- Pound Bend, Warrandyte

- Mount William stone axe quarry near Lancefield: tool making[42][43]

- Dights Falls area: meeting place for corroborees, Mission School location, Native Police Corps.[44]

- Heide Gallery, Templestowe: Scarred Tree.[45]

- Merri Creek including the Treaty Site with John Batman.[46]

- Solomons Ford on the Maribyrnong River: location of fish and eel traps.[47]

- Lily Street Lookout, Avondale Heights: location of a silcrete quarry for stoneworking.[48]

- Brimbank Park, Keilor. Over 25 archeological sites.[49]

- Taylors Creek Quarry, Keilor.[50]

- The Sunbury earth rings, Sunbury.[51]

- Coranderrk Mission Station, Healesville.[52]

- Mount Macedon axe sharpening site.[53]

Notes

- Presland: "There is some evidence to show that people were living in the Maribyrnong River valley, near present day Keilor, about 40,000 years ago." (Presland 1997, p. 1)

- William Thomas, Quarterly Report, 30 November 1844, quoted in Rowley 1970, p. 60

Citations

- Bill 2011.

- Pascoe 1947.

- Presland 1994.

- Presland.

- Brown.

- Steyne 2001.

- Rhodes 2003, p. 23.

- Rhodes 2003.

- Hunter 2004–2005.

- Langhorne 2002.

- Fleming 2002.

- Broome 2005, pp. 7–9.

- Thomas 1898.

- Batmania.

- Web 2005.

- Ellender & Christiansen 2001, pp. 18–23.

- Broome 2005, pp. 10–14.

- National Archives of Australia, p. I.

- Clark 2005.

- Gannaway 2007.

- Ellender & Christiansen 2001, pp. 65–67.

- Broome 2005, pp. 106–7.

- Broome 2005, p. 126.

- Presland 1994, pp. 104–105.

- Broome 2005, p. 92.

- Wiencke 1984.

- Ellender & Christiansen 2001, pp. 87–92.

- Ellender & Christiansen 2001, p. 45.

- Hinds 2002.

- Thompson 2007.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 8–9.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 76–77.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 80–81.

- Toscano 2008.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 14–17.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 90–91.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 18–19.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 86–87.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 20–21.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 98–99.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 6–7, 24–27.

- National Heritage List.

- McBryde 1984.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 28–31.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 22–23.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 32–37.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 60–61.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 62–63.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 64–69.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 70–71.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 92–97.

- Eidelson 2000, pp. 113–114.

- WTC: resource management.

Sources

- "The Abbotsford Convent Muse, Issue 18" (PDF). September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS. 18 June 2021.

- "Ancestors & Past". Wurundjeri Tribe Council. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Barwick, Diane E. (1984). McBryde, Isabel (ed.). "Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835-1904". Aboriginal History. 8 (2): 100–131. JSTOR 24045800.

- "Batmania: The Deed, National Museum of Australia". Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Bill, Gammage (2011). The biggest estate on earth: how Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1742693521. OCLC 903290230.

- Broome, Richard (2005). Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-569-4.

- Brown, Peter. "The Keilor Cranium". Peter Brown's Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Clark, Ian D. (1 December 2005). ""You have all this place, no good have children ..." Derrimut: traitor, saviour, or a man of his people?". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society.

- Decision in relation to an Application by Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc to be a Registered Aboriginal Party. Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. 22 August 2008.

- Eidelson, Meyer (2000) [First published 1997]. The Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Ellender, Isabel; Christiansen, Peter (2001). People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days. Merri Creek Management Committee. ISBN 978-0-9577728-0-9.

- Flanagan, Martin (25 January 2003). "Tireless ambassador bids you welcome". The Age. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- Fleming, James (2002). Currey, John (ed.). A journal of Grimes' survey: the Cumberland in Port Phillip January–February 1803. Banks Society Publications. ISBN 978-0949586100. cited in Rhodes 2003, p. 24

- Gannaway, Kath (24 January 2007). "Important step for reconciliation". Star News Group. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "Governor Bourke's Proclamation 1835 (UK)". National Archives of Australia: I. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Hinds, Richard (24 May 2002). "Marn Grook, a native game on Sydney's biggest stage". The Age. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Hunter, Ian (2004–2005). "Yarra Creation Story". Wurundjeri Dreaming. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Interview with Megan Goulding, CEO Wurundjeri Inc" (PDF). Abbotsford Convent Muse. No. 18. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Langhorne (2002). Introduction. The Life and Adventures of William Buckley, by John Morgan, 1852. By Flannery, Tim. Flannery, Tim (ed.). ISBN 978-1-877008-20-7.

- "Management of Wurundjeri Properties & Significant Places". Wurundjeri Tribe Council. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- McBryde, Isabel (October 1984). "Kulin Greenstone Quarries: The Social Contexts of Production and Distribution for the Mt William Site". World Archaeology. 16 (2): 267–285. doi:10.1080/00438243.1984.9979932. JSTOR 124577.

- "National Heritage List: Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry". Department of the Environment and Energy. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Pascoe, Bruce (1947). Dark emu black seeds: agriculture or accident?. ISBN 978-1922142443. OCLC 930855686.

- Presland, Gary. "Keilor Archaeological Site". Online Encyclopedia of Melbourne (eMelbourne). Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Presland, Gary (1994). Aboriginal Melbourne. The lost land of the Kulin people. McPhee Gribble.

- Presland, Gary (1997). The First Residents of Melbourne's Western Region. Harriland Press.

- Rhodes, David (August 2003). "Channel Deepening Existing Conditions Final Report – Aboriginal Heritage" (PDF). Parsons Brinckerhoff & Port of Melbourne Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Rowley, C.D. (1970). The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. Penguin Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-14-021452-9.

- Steyne, Hanna (2001). "Investigating the Submerged Landscapes of Port Phillip Bay, Victoria" (PDF). Heritage Victoria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Thomas, William (1898). Bride, Thomas Francis (ed.). Letters from Victorian Pioneers. Public Library of Victoria.

- Thompson, David (27 September 2007). "Aborigines were playing possum". Herald Sun. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Wurundjeri (VIC)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Toscano, Joseph (2008). Lest We Forget. The Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner Saga. Anarchist Media Institute. ISBN 978-0-9758219-4-7.

- Wandin, James (26 May 2000). "An address to the Parliament of Victoria". Parliament of Victorian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Web, Carolyn (3 June 2005). "History should have no divide". The Age. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Wiencke, Shirley W. (1984). When the Wattles Bloom Again: The Life and Times of William Barak, Last Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. S.W. Wiencke. ISBN 978-0-9590549-0-3.