Wojciech Fangor

Wojciech (pronounced: /vɒɪtʃɛx/ VOY-tche-kh) Bonawentura Fangor (15 November 1922 – 25 October 2015), also known as Voy Fangor, was a Polish painter, graphic artist, sculptor. Described as "one of the most distinctive painters to emerge from postwar Poland", Fangor has been associated with Op art and Color field movements and recognized as a key figure in the history of Polish postwar abstract art.[1] As a graphic artist, Fangor is known as a co-creator of the Polish School of Posters.

Wojciech Fangor | |

|---|---|

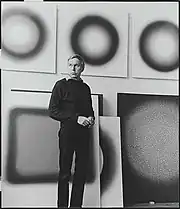

Wojciech Fangor posing in front of his paintings in 1964 | |

| Born | 15 November 1922 Warsaw, Poland |

| Died | 25 October 2015 (aged 92) Warsaw, Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Education | Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw |

| Movement | Op-art, Color field, Polish School of Posters |

| Spouse | Magdalena Fangor |

| Awards | Order of Polonia Restituta |

| Signature | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

After briefly conforming to the style of Socialist Realism during the Stalinist regime in Poland, Fangor had moved toward non-objective painting by the late 1950s. Fangor's 1958 exhibition titled Studium Przestrzeni at Salon Nowej Kultury in Warsaw, organized together with Stanisław Zamecznik, sought to incorporate Fangor's abstract paintings into the surrounding environment, becoming the foundation for his subsequent experiments with the spatial dimension of color. Between 1953 and 1961, he designed over one hundred posters working alongside Henryk Tomaszewski and Jan Lenica, among others.

In 1966, following a period of extensive international travel, Fangor relocated to the United States where he achieved a level of commercial success, critical reception, and direct exposure to American post-war visual culture largely inaccessible to most contemporary artists from the Eastern Bloc. In 1970, he became the first Polish artist to hold a solo exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.[2] Fangor returned to Poland in 1999 where he remained active until his death in 2015, although his international recognition had by then diminished. For his contributions to the Polish culture, Fangor was awarded several honors, including the Order of Polonia Restituta in 2001, the country's second highest civilian order, and the Gold Medal for Merit to Culture in 2004.[3] His works are included in the permanent collections of museums in Europe, North America, and the Middle East.

Life and early career

Early life and work (1922-1940s)

Wojciech Bonawentura Fangor was born on 15 November 1922 in Warsaw to an affluent family. His father, Konrad Fangor, an engineer, has been described as a "wealthy prewar entrepreneur",[4] and a founder of Technical Society for Trade and Industry in Warsaw, while his mother, Wanda née Chachlowska, was a trained pianist. The artist's mother is said to have played an important role in encouraging her son's creative interests.[5] Prior to the outbreak of World War II, Fangor studied first at the private grammar school of Masovian School Society and then attended Mikolaj Rey Grammar School in Warsaw.[5]

Since 1936, he trained as a painter under Tadeusz Kozłowski. The artist was exposed to the European canon during travels to Venice and Florence in 1936 and Rome, Naples, and Paris in 1937 (he saw Pablo Picasso's Guernica at the Paris World Exposition that year).[5] During World War II Fangor studied art privately under Felicjan Kowarski, who stayed at Fangor family's country estate in Klarysew for several years during the Nazi occupation of Poland, and later Tadeusz Pruszkowski. Fangor obtained his diploma in 1946 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw.[2]

Post-war Poland and Stalinist regime (1947-1956)

Following the end of World War II and the Yalta Conference, Poland came under the political influence of the Soviet Union and by 1947—as a result of rigged election—the Stalinist regime under Bolesław Bierut had consolidated political control of the country.[6] During the late 1940s, Fangor supported himself by working on official government projects, including a 1948 large-scale figurative panel in Warsaw depicting silhouettes of workers to celebrate the Unification Congress of the Polish Workers' Party and Polish Socialist Party that took place at Warsaw University of Technology between 15 and 21 December 1948, a consequential political event that is said to have officially turned Poland into a Soviet satellite state.[5]

The new cultural doctrine of Socialist Realism, which imposed naturalistic visual vocabularies and mandated that artists focus on themes relating to everyday life under socialism, was officially introduced in 1949. By the following year, Fangor began painting Socialist Realist compositions. In 1951, he participated in the Second Nationwide Display of Plastic Arts, the second official exhibition of Polish Socialist Realist painting and sculpture organized by the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych) at Zacheta National Gallery of Art, where his compositions titled Matka Koreanka (Korean Mother) from 1951 and Lenin w Poroninie (Lenin in Poronin) from 1951 were awarded the Second Prize for Painting.[7][Note 1] The former was praised by state-controlled press for its poignant criticism of the Korean War and for challenging what the Soviet Union propaganda defined as colonialist and imperialist ambitions of the United States.[8]

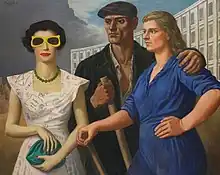

In the early 1950s, Fangor had completed multiple Socialist Realist works, including an oil painting titled Postaci (Figures) from 1950 which had not met with critical success at first, but which would later become one of the artist's most recognized figurative compositions, interpreted as "an archetypal expression of the Stalinist exaltation of production over consumption."[9][10] The artist also began to incorporate Socialist Realist vocabulary into graphic design and several of his agitprop posters, made between 1951 and 1952, were awarded prizes at the Second National Poster Exhibition in 1952.[5] Even though Fangor had been intrigued by the idea of collective artistic action as a means of rebuilding Poland in the aftermath of World War II, he had eventually become disenchanted with Socialist Realism which he saw as an ineffective tool of enacting social or political change.[11]

Polish School of Posters (1950s)

In 1953, Fangor was employed as an assistant professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, a position he held until 1961.[12] Following Joseph Stalin's death in 1953 and the subsequent Khrushchev's thaw, Fangor began to turn away from Socialist Realism in favor of non-figurative visual idioms. During the early 1950s, Fangor supported himself through graphic design and became one of the co-founders of what would later be known as the Polish School of Posters, together with Jan Lenica, Henryk Tomaszewski and others.[13]

The history of Polish School of Posters goes back to 1947 when state-controlled film agency, Film Polski, began to hire artists to create posters for movies distributed in early communist Poland. All films were heavily censored and posters "were not allowed to incorporate any shots of actors, titles, or film stills."[14] However, it was not until the thaw that poster design would flourish, rebelling "against the limits of advertising, the psychology of advertising and propaganda techniques," incorporating avant-garde vocabularies.[13] As scholar Dorota Kopacz-Thomaidis observes, the Polish School of Poster "offered an artist-driven, painterly approach to the art of poster, based on ambiguity and metaphor."[13] In his design for Andrzej Wajda's acclaimed Ashes and Diamonds from 1958, for instance, Fangor incorporated "handwritten text, framed though as a painting, in a three-colour palette scheme" to render "the complexities of the film."[13] In the period 1953–1961, Fangor designed about 100 posters.[2]

Later career and international recognition

After the thaw (1958-1966)

By 1958, Fangor had begun developing his distinct visual idiom that incorporated and combined large areas of blurred in a variety of quasi-geometrical, abstract forms, initially painted in black and white. It was the foundation of his subsequent artistic experiments, "where color, light, space, and a temporal perception remained fundamental aspects of pictorial expression."[15] These ideas were reflected in Fangor's first "painting environment," an exhibition space that incorporated paintings into the surrounding environment, titled Studium przestrzeni (Study of Space) (1958) designed together with Stanisław Zamecznik at Salon Nowej Kultury in Warsaw.[5]

Emphasizing the spectator's physical experience, Fangor called this a “Positive illusory space". Unlike traditional form of painting, what Fangor described as “Renaissance hole-in-the-wall through which the spectator is compelled to look", contemporary painting according to the artist's own writings was supposed to have a direct impact on its surrounding and "radiate a force onto literal space which defines a zone of physical activity".[16] Fangor's installation, shown to the public six years prior to Robert Morris's breakthrough Minimalist exhibition at New York's Green Gallery, would become one of the earliest studies of phenomenological properties of abstract art in post-war Europe.[Note 2][17]

While the exhibition was a radical experiment in incorporating painting into its surrounding space, and first such work in Polish post-war avant-garde, it was not well received by contemporary critics. Even though the cultural thaw had embraced abstraction by the late 1950s, art criticism focused on a traditional form of painting—and ways in which abstract art can counter the previously imposed Socialist Realism—rather than the kind of spatial experimentation embodied by Fangor's installation.[18] It was not until the 1960s that Studium Przestrzeni would be recognized as a radical and influential intervention in the history of Polish post-war avant-garde.[5] The artist later recalled that his intention to leave Eastern Europe to "confront his ideas" in the late 1950s had grown stronger as a result of the initial critical reception to the 1958 installation.[19]

Early international recognition (1959-1962)

The following year, several of Fangor's abstract paintings were included in a group exhibition organized at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, providing the artist with a chance to showcase his recent work outside of the Iron Curtain. Around that time, the artist started to turn away from his earlier monochromatic palette in favor of color compositions.[15] He also began focusing on the circle, a geometric form that would become the most recognizable motif in his paintings and constitute the compositional basis for over four hundred works on canvas completed between 1958 and 1978.[20] At Stedelijk, Fangor and Zamecznik created another environment installation titled Color in Space where diverse "geometric forms and bright color zones in red, blue, and black affected the space of the exhibition and the constantly changing vision of the spectator."[15] In 1960, the artists published a Manifesto, in which they reiterated a commitment to moving beyond the picture plane and heightening the viewer's perception of the physical space.[15]

Crucial to Fangor's subsequent exposure to the West was his encounter with Beatrice G. Perry, the co-founder of Gres Gallery in Washington, D.C., who represented Yayoi Kusama and Fernando Botero, among other international contemporary artists. She had visited Poland in 1959 with hopes of finding new Eastern European artists to include in the Gres roster and taken a great interest in Fangor's idiosyncratic abstract idiom.[15] Perry, along with her business partner Thomas Baker Slick, became an important patron of Fangor in the United States and helped promote his work among American collectors and curators. Scholar Magdalena Dabrowski sees Perry's enthusiasm for the work of Fangor critical to his subsequent participation in two major survey exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Fifteen Polish Painters in 1961 and The Responsive Eye in 1965, the latter being a birthplace of Op Art movement.[15]

Curated by Peter Selz, who had traveled to Poland in 1960 and 1961 to select paintings for the exhibition, Fifteen Polish Painters included works by Wojciech Fangor, Henryk Stażewski, Stefan Gierowski, Aleksander Kobzdej, Tadeusz Kantor, and Jerzy Nowosielski, among others.[21] Focused primarily on non-figurative painting, the 1961 show emphasized the importance of abstraction in the history of Polish modern art.[22] In drawing a direct comparison between abstract art and freedom, an approach embodied by the visually liberated works of Abstract expressionism which the U.S. government had fervently promoted abroad, the exhibition served as a symbolic repudiation of Soviet politics and Socialist Realism during the Cold War.[23] Writing in the exhibition catalogue, Selz emphasized the strong visual interaction between Fangor's paintings and surrounding environment:

A muralist and interior designer, Fangor is less interested in the single easel painting than in organizing a larger environment and, at best, his canvases should be seen placed in close proximity and at right angles to each other (...) Here he attains the pulsating optical effect of color on space which he desires.

— Peter Selz, 15 Polish Painters (exh. cat.), New York: The Museum of Modern Art (1961), p. 9.

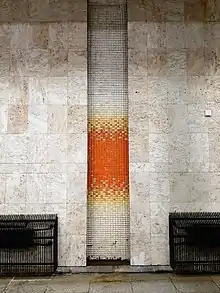

While the early 1960s in Fangor's career were marked by frequent international travel, the artist continued to do limited work in Poland until 1962. Between 1960 and 1962, Fangor was commissioned to decorate train platforms of the newly re-constructed Warszawa Srodmiescie PKP railway station in Warsaw.[26] Fangor designed a series of abstract wall and ceiling mosaics that recalled the artist's investigations into the immersive properties of color in painting and its impact on the spectator. The shifting hues of mosaics set a visual rhythm and were meant to seamlessly integrate five colors (red, orange, yellow, blue, and green) into the station's architectural interior. Unlike Studium Przestrzeni, however, the Srodmiescie mosaics also had a practical application and were intended to help passengers navigate the platforms: red, orange, and yellow mosaics indicated east, while green and blue directed passengers moving westward.[24]

Travels and ICA Fellowship (1961-1966)

In 1961, Fangor left his teaching position at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts and moved to Vienna. The following year, he was invited to participate in a fellowship at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Washington, D.C. funded by the Ford Foundation, providing an artist from the Eastern Bloc with a rare opportunity to lecture at universities across the U.S. and interact with key figures of American post-war art scene, including Josef Albers, Mark Rothko, and Robert Goldwater.[23]

Rothko's Abstract expressionist works consisting of large swaths of color are said to have made an impact on Fangor, even though he had not shared the former artist's interest in the emotional and spiritual qualities of painting.[15] While in the U.S., Fangor also interacted with Clement Greenberg, an American critic and a champion of Abstract expressionism, who found little interest in the artist's ideas pertaining to spatial interaction and insisted that Fangor move toward the "liquefied, poured colors" of Helen Frankenthaler or Kenneth Noland if he were to achieve commercial success.[15] While Fangor had generally benefited from the exposure to various Western artistic vocabularies, he did not see his participation in the ICA fellowship as an act of political defiance against the communist regime and in private correspondence acknowledged that the funding had provided him primarily with space and means to continue developing his own abstract vocabulary.[23]

Later that year, upon completion of the ICA Fellowship, Fangor moved to Paris. In February 1964, he had his first solo exhibition at Galerie Lambert in Paris and in June that year, he held an individual show at Städtisches Museum Schloss Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Germany. Also in 1964, he was awarded a grant from Ford Foundation to live and work in Berlin. Fangor lived in Berlin for one year before leaving for London, where he stayed for six months.[5]

In 1965, William C. Seitz, curator at the Museum of Modern Art who had visited Europe in 1963 and seen Fangor's exhibition in Paris, decided to include Fangor's painting in his show the Responsive Eye.[5] The exhibition was pivotal in defining Op art as movement and later traveled to several museums across the U.S., including the Seattle Art Museum, the Pasadena Art Museum (now Norton Simon Museum), and the Baltimore Museum of Art. Despite being poorly received by contemporary critics, Responsive Eye proved hugely popular with the general public and, bolstered by the significant institutional influence of MoMA, is said to have positively influenced the commercial success of the participating artists.[27][28]

Fangor's inclusion in the exhibition had an important impact on the artist's work being classified as op art in the subsequent decades, although critics have generally struggled to pinpoint the specific movement Fangor's work belonged to. In 2021, for instance, critic and art historian Karen Wilkin described one of his paintings as "a blurred version of a Noland Circle," alluding to the visual similarities between Fangor's style and that of artists associated with the color field movement.[29]

United States (1966-1999)

Fangor eventually settled permanently in the United States in 1966 where he was offered a teaching job at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey.[30] In 1970 he became the first Polish artist to have an individual exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.[1] In a review for the New York Times, critic John Canaday found some parallels between Fangor's organic shapes and Jean Arp's biomorphic forms of the Surrealist period and compared his technique to that of Color field painters. At the same time, Canaday acknowledged the difficulty of establishing an authentic art historical precedent to the artist's idiosyncratic large-scale and highly vibrant non-mimetic paintings. He described Wojciech Fangor as "the great romantic of Op Art, working not by rule but by a combination of intuition and experiment, appealing not to reason but to our yearning toward the mysterious."[31]

Return to Poland (1999-2015)

In 1999, Wojciech Fangor returned to Poland where he continued to exhibit his work. While the artist continued to be celebrated in his home country, Fangor's recognition abroad had by then diminished. The Swiss collector and auctioneer Simon de Pury opined in 2015 that Fangor would have a "much higher" profile had he decided to remain in the U.S.[32] The first monographic publication devoted to the artist's career, titled Wojciech Fangor. Malarz przestrzeni (Wojciech Fangor. Painter of Space) and edited by art historian Bozena Kowalska, was published in 2001. Two years later, a major retrospective exhibition of Fangor's oeuvre was held at the Center for Contemporary Art at Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw. In 2004, his paintings were included in a survey show titled Beyond Geometry: Experiments in Form, 1940s-1970s at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (later traveling to Pérez Art Museum Miami), which brought together examples of "European and Latin American concrete art, Argentine Arte Madí-Brazilian Neo-Concretism, Kinetic and Op Art, Minimalism, and various forms of post-minimalism" and positioned Fangor's work within the context of global post-war tendencies in abstract art.[33]

Warsaw Metro M2 murals (2007)

In 2007, Fangor was asked to design decorative wall murals for seven underground stations of the new line of the Warsaw Metro.[34] Utilizing vibrant and highly contrasting colors, each mural spelled out the name of the corresponding station with large-scale lettering, reflecting Fangor's earlier engagement with graphic design and typography. Moreover, the Warsaw Metro murals represented the artist's return to using color as a means of conditioning the surrounding environment and eliciting participatory reaction from the spectator, similarly to the mosaics Fangor designed in the early 1960s for Srodmiescie PKP station.[34]

Wojciech Fangor died in 2015 aged 92 and was survived by his wife, Magdalena Shummer-Fangor, and two children. At the time of his death, he resided in Błędów, Grójec County, a village near Warsaw.[35]

Legacy

Collections

Wojciech Fangor's work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the National Museum, Warsaw, and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, among other institutions worldwide.

Art market

In 2020, M22 from 1969 sold for US$1.65 million at Desa Unicum Auction House in Warsaw, which at the time set an auction record for the highest price paid for painting by a Polish artist.[36]

Selected works

Signature, Stadion Narodowy metro station

Signature, Stadion Narodowy metro station

Permanent exhibition, Museum of Warsaw

Permanent exhibition, Museum of Warsaw.jpg.webp) Selection of paintings by Fangor

Selection of paintings by Fangor

Notes

- Different categories of awards were given based on medium, divided into Painting, Sculpture, and Graphic Arts.

- For a seminal study on the relationship between Minimalism and phenomenology in the United States, see Potts (2001) in the References list

Citations

- Grimes, William (9 November 2015). "Wojciech Fangor, Painter Who Emerged From Postwar Poland, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Gorządek, Ewa; Le Nart, Agnieszka (2015). "Wojciech Fangor". Culture.pl. Warsaw: Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- Official Website of the President of the Republic of Poland (17 January 2011). "Prezydent odznaczył ludzi kultury". prezydent.pl (in Polish).

- Wicha, Marcin (2008-12-06). "Fangor: od "Lenina w Poroninie" do designu". Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (Newspaper) (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-01-04.

His father was a wealthy prewar entrepreneur. (Polish: Ojciec był bogatym przedwojennym biznesmenem.)

- Jankowska-Cieślik, Katarzyna (2018). "Chronology". In Dabrowski, Magdalena (ed.). Wojciech Fangor. Color and Space. Milan: Skira Editore. pp. 199–215. ISBN 978-88-572-3285-0.

- Rothschild, Joseph (2008). "Chapter 3: Communists Come to Power". Return to Diversity: a Political History of East Central Europe Since World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 61–100. ISBN 9780195334746.

- II Ogólnopolska wystawa plastyki. Malarstwo – rzeźba – grafika (Exhibition catalogue) (in Polish). Warsaw: Zachęta Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych. 1951.

- Szczerski, Andrzej (2016). "Chapter 33. Global Socialist Realism: The Representation of Non-European Cultures in Polish Art of the 1950s". In Bazin, Jérôme; Dubourg Glatigny, Pascal; Piotrowski, Piotr (eds.). Art beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945-1989). Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 439–452. ISBN 978-963-386-083-0.

- Reid, Susan E.; Crowley, David, eds. (2000). Style and Socialism. Modernity and Material Culture in Post-War Eastern Europe. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 9781859732342.

- Sosnowska, Dorota (2014). Królowe PRL : sceniczne wizerunki Ireny Eichlerówny, Niny Andrycz i Elżbiety Barszczewskiej jako modele kobiecości (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. ISBN 978-83-235-1203-5. OCLC 898417927.

- Sienkiewicz, Karol (December 2010). "Korean Mother. Wojciech Fangor". Culture.pl. Warsaw: Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- "Wojciech Fangor. Artysta optyczny". PolskieRadio24.pl. Polish Radio. 25 October 2022. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- Kopacz-Thomaidis, Dorota (2019). "The Polish School of Poster". Wnętrze. Zewnętrze. Przestrzeń wspólna (Interior. Exterior. Common Space). Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT. 1: 99–115. doi:10.23817/2019.wnzewn-9. ISBN 978-83-7977-439-5.

- Malmstrom, Susan; Roskewitch, Annamaria (2020-12-01). "Polish Posters". Los Angeles Archivists Collective. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- Dabrowski, Magdalena (2018). "Fangor's Innovations: In Search of New Meaning of Color, Light, and Space". Wojciech Fangor. Color and Space. Milan: Skira Editore. pp. 12–28. ISBN 978-88-572-3285-0.

- After Tomaszewski (2018), original text: “Wojciech Fangor: Polish Artist” (1962) Essay authored by Fangor while at Ohio State University in March 1962. Institute of Contemporary Art Records. Washington, D.C.: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- Potts, Alex (2001). The Sculptural Imagination. Figurative, Modernist, Minimalist. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088014.

- Szydlowski, Stefan (2015). Wojciech Fangor. Wspomnienie terazniejszosci (exhibition catalogue) (in Polish). Wroclaw: National Museum. p. 11. ISBN 978-8-36-533800-6.

- Fangor, Wojciech (1990). "Fangor o sobie". Wojciech Fangor: 50 lat malarstwa (exhibition catalogue) (in Polish). Warsaw: Zacheta National Gallery of Art. p. 16.

- Rosenthal, Mark (2018). "Wojciech Fangor's Celebration of the Circle". In Dabrowski, Magdalena (ed.). Wojciech Fangor: Color and Space. Milan: Skira Editore. pp. 29–37. ISBN 978-88-572-3285-0. OCLC 954224521.

- Selz, Peter (1961). 15 Polish painters (PDF) (exhibition catalogue). New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

- A notable exception was the figurative work of Jerzy Nowosielski.

- Tomaszewski, Patryk (2018). "Wojciech Fangor's Movement in the Early 1960s". Wojciech Fangor. The Early 1960s. New York: Heather James Fine Art. pp. 4–11.

- Lewicki, Jakub (2020). "Unikatowa dekoracja mozaikowa Dworca Warszawa-Śródmieście w rejestrze zabytków". Mazowiecki Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków (Masovian Voivodeship Monument Conservation). Warsaw. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- Cserna, George (1965). "Unidentified visitor at the exhibition, "The Responsive Eye." | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. February 25, 1965–April 25, 1965. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN757.10. Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- Urzykowski, Tomasz (12 November 2020). "Unikatowe mozaiki Fangora z Dworca Śródmieście uznane za zabytek". warszawa.wyborcza.pl. Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- Medosch, Armin (2016). New Tendencies: Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961-1978). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-262-03416-6. OCLC 925426404.

- Smith, Roberta (2017-04-11). "Julian Stanczak, Abstract Painter, Dies at 88". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- Wilkin, Karen (January 2021). "Jules Olitski in New York". New Criterion. 39 (5): 42–45.

- "Wojciech Fangor: artysta niezłomny". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 2014-09-02. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- Canaday, John (1970-02-15). "Fangor's Romantic Op". The New York Times. p. 103. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- Michalska, Julia (26 October 2015). "Polish Op artist Wojciech Fangor dies at 92". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- Zelevansky, Lynn, ed. (2004). Beyond Geometry. Experiments in Form, 1940s-1970s (exhibition catalogue). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262240475.

- Gliński, Mikołaj (5 March 2015). "Stations as Canvas: Painting the Warsaw Metro". Culture.pl. Warsaw: Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- "Wojciech Fangor nie żyje". Newsweek.pl (in Polish). 25 October 2015. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- A. M. (12 December 2020). "Rekordy na polskim rynku sztuki: 7 mln za Fangora, 4,5 mln za Lempicką". Rynek i Sztuka (in Polish). Wrocław: Media&Work Agencja Komunikacji Medialnej. Retrieved 2023-01-04.