Women in Syria

Women in Syria constitute 49.9% of Syria's population. According to World Bank data from 2021, there were around 10.6 million women in Syria.[6] They are active participants not only in everyday life, but also in the socio-political fields. Syrian women and girls still experience challenges in their day-to-day lives, for example in the area of law and health care.

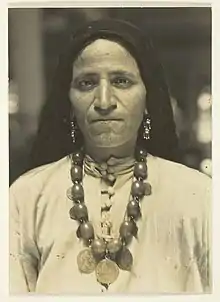

Syrian woman on Ellis Island in 1926. Phothograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 31 (2019)[1] |

| Women in parliament | 13% (2015)[2] |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 40% (2019) |

| Women in labour force | 18.9% (2021)[3] |

| Gender Inequality Index[4] | |

| Value | 0.477 (2021) |

| Rank | 119th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[5] | |

| Value | 0.568 (2021) |

| Rank | 152nd out of 156 |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

History

In the 20th century, a movement for women's rights developed in Syria, made up largely of upper-class, educated women.[7] In 1919, Naziq al-Abid founded Noor al-Fayha (Light of Damascus), the city's first women's organization, alongside an affiliated publication of the same name. She was made an honorary general of the Syrian Army after fighting in the Battle of Maysaloun, and in 1922, she founded the Syrian Red Crescent.[8] In 1928, Lebanese-Syrian feminist Nazira Zain al-Din, one of the first people to critically reinterpret the Quran from a feminist perspective, published a book condemning the practice of veiling or hijab, arguing that Islam requires women to be treated equally with men.[9] In 1930, the First Eastern Women's Congress was hosted in Damascus by the Syrian-Lebanese Women's Union.

In 1963, the Ba'ath Party took power in Syria, and pledged full equality between women and men as well as full workforce participation for women.[10]

In 1967, Syrian women formed a quasi-governmental organization called the General Union of Syrian Women (GUSW), a coalition of women's welfare societies, educational associations, and voluntary councils intended to achieve equal opportunity for women in Syria.[10]

The year 2011 marked the beginning of the Syrian Civil War, which saw many civilians fall victim to attacks targeting hospitals, schools, and infrastructure. Extremist rebel groups, such as Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS, have enforced strict policies restricting the freedoms of women in territories they control.[11]

After the outbreak of civil war, some Syrian women have joined all-female brigade units in the Syrian Arab Army,[12] the Democratic Union Party,[13] and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant,[14] taking on roles such as snipers, frontline units, or police.

Legal rights

While Syria has developed some fairly secular features during independence in the second half of the 20th century, personal status law is still based on Sharia[15] and applied by Sharia Courts.[16] Syria has a dual legal system which includes both secular and religious courts.[17] Marriage contracts are between the groom and the bride's father, and Syrian law does not recognize the concept of marital rape.[18]

Syrian family law thus has a large impact on the legal rights of women. Public law states that all Syrian citizens are equal. However, family law has judicial primacy in defining women's personal status. In certain cases, family law can invalidate constitutional law.[19] Although there were efforts to secularize the legal system of most Arab states in the 1920s, family law is still heavily influenced by religion and has an impact on the private domain in cases such as marriage, divorce, and child custody.[20]

In 2002, Syria signed the CEDAW but set reservations related to family law.[21]

Education

The early schooling in Syria starts at six years old and ends at the age of eighteen. In Syrian universities, women and men attend the same classes. Between 1970 and the late 1990s, the female population in schools dramatically increased. This increase included the early school years, along with the upper-level schools such as universities and higher education. Although the number of women has increased, there are still ninety five women to every one hundred men. Although many women start going to school, the dropout rate for women is much higher than for men.

The literacy rate for women is 74.2 percent and 91 percent for men. The rate of females over 25 with secondary education is 29.0 percent.[22]

Politics

In Syria, women were first allowed to vote and received universal suffrage in 1953.[23] In the 1950s, Thuraya Al-Hafez ran for Parliament, but was not elected. By 1971, women held four out of the 173 seats.[24]

The current president of Syria is a male. There are also two vice presidents (including female vice president Najah al-Attar since 2006), a prime minister and a cabinet. As of 2012, in the national parliament men held 88% of the seats while women held 12%.[25] The Syrian Parliament was previously led by female Speaker Hadiya Khalaf Abbas, the first woman to have held that position.[26]

President Assad's political and media adviser is Bouthaina Shaaban. Shaaban served as the first Minister of Expatriates for the Syrian Arab Republic, between 2003 and 2008,[27] and she has been described as the Syrian government's face to the outside world.[28]

Of the civil society representatives among the 150 members of the Syrian Constitutional Committee, which was assembled in 2019 by the Syria Envoy of the United Nations, Syrian women comprise around 30%.[29] Several renowned Syrian women, such as academic Bassma Kodmani, Sabah Hallak of the Syrian Women's League, the law professor Amal Yazji or the judge Iman Shahoud, sit on the committee's influential 'Small' or Drafting Body.[30]

Role in economy and in the military

In 1989 the Syrian government passed a law requiring factories and public institutions to provide on-site childcare.[10]

However, women's involvement in the workforce is low; according to World Bank, as of 2014, women made up 16.4% of the labor force.[31]

Women are not conscripted in the military, but may serve voluntarily. The female militias of Syria are trained to fight for the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad. A video was found dating back to the 1980s with female soldiers showing their pride and protectiveness toward Assad's father.[32] "Because women are rarely involved in the armed side of the revolution, they are much less likely to get stopped, searched, or hassled at government checkpoints. This has proved crucial in distributing humanitarian aid throughout Syria."[33]

Women's health

In 2020, the World Bank estimated the life expectancy of Syrian women on 76 years, in comparison to 69 years for men. This number has increased significantly since the mid 2010s.[34] The number of women that survive to the age of 65 has also increased: from 73% in 2014 to 84% in 2020.[35] The adolescent fertility rate has decreased since 2015. 39 in every 1000 girls between the ages of 15 and 20 gave birth in 2020. This was lower than previous years and lower than the average rate in the same income group.[36]

Despite the improvement of these numbers, there is still a high need for action to lessen the suffering of women and girls as a result of the ongoing crisis in Syria. The United Nations Population Fund stated in 2022 that 7.3 million women and girls need life-saving sexual and reproductive health care due to hostile circumstances, drought, economic collapse, and displacement. An example is maternal care, because the number of women that die during pregnancy and childbirth is on the rise and higher in Syria than in neighboring countries.[37]

Impact of the conflict on Syria's women

Since the conflict erupted in 2011, women in Syria, namely in conflict zones, have been facing violence, sexual assault, forced displacement, detention, domestic violence, child marriage and other violations of their rights.[38][39]

During the years of conflict, insecurity and the economic collapse significantly increased the vulnerability of women and girls.[40] In addition, many girls were left without schooling or access to healthcare services.[40][41] The enrolment rate for primary education was 61% in 2013, with 61.1% of the total number being female, while for secondary education, the rate was 44% in 2013 - 43.8% for female.[41]

In 2015, the United Nations gathered evidence of systematic sexual assault of women and girls by combatants in Syria, and this was escalated by the Islamic State (ISIL) and other terrorist organizations.[41][42]

Sexual abuse has been recognized as the dominant form of violence experienced by women and girls in Syria since the outbreak of the conflict. This often occurred within their own homes or in detention, alongside other forms of assault such as torture, abduction and at times even murder. This was frequently carried out in the presence of a male relative. [43]

Impact of the conflict on Yezidi women

The Syrian conflict has had a devastating impact on Syria's Yezidi people. The Yezidi community, a religious minority group, has faced brutality and persecution at the hands of the extremist group ISIS, which considers them as 'unbelievers'. Since the groups occupation of the region inhabited by the Yezidis in Northern Syria, thousands of Yezidis have been kidnapped, killed and raped. As a result, many surviving Yezidis fled Syria, leaving behind a divided and heavily traumatized community. [44]

During their occupation of the areas inhabited by the Yezidis, Yezidi men were executed on the spot and the women and girls were kidnapped and exploited as sex slaves, as well as raped and tortured by the ISIS fighters. Some of these girls were just 6 years old. [45]

While a few women were able to escape their kidnappers and reunite with their families, numerous others remain missing, leaving their families uncertain about their fate and whether they are still alive. ISIS's operations of mass kidnapping and human trafficking resulted in an estimated 7000 women being victimized and over 3000 women are still missing. [46]

Crime against women

Honor killings

Honor killings take place in Syria in situations where women are deemed to have brought shame to the family, affecting the family's 'reputation' in the community. Some estimates suggest that more than 200 honor killings occur every year in Syria.[47]

These killings are carried out as a means of restoring the family's honor. The concept of these honor killings is deeply rooted in traditional and patriarchal norms. These killings can take shape in different forms including murder, severe psychological and physical abuse and mutilation. Usually these killings or punishments are committed by male family members. It is believed that they have the authority to reinstall the family's honor. Reports have revealed that women in Syria who come from poor households are more likely to be exposed to honor killings. [48]

Usually the victims of these honor killings include women who engage in adultery, premarital sex (or relationships), seek a divorce or refuse a forced marriage. Sometimes it also happens to women who have become victims of sexual assault. [49] Men can also become victims of honor killings, but this happens to a lesser extent. [50]

Forced and child marriage

The conflict in Syria has led to an increase in child marriages. The harsh living conditions, the insecurity, and the fear of rape, have led families to force their daughters into early marriages.[51] [52] As a result of early marriage, many girls in Syria are forbidden from completing their studies because when a girl is married she is only expected to be a good wife and a good mother as well. Child marriage can influence physical and mental health badly. Physical damage can be related to child bearing specially for women under 18 years old and the possibility for not being able to give birth later in life, and in extreme cases it can lead to death. Psychological factors can be defined as difficulties in interacting with the husband or not having enough awareness about marriage life and its responsibilities.[53]

Domestic Violence

A study covering the low-income women in Aleppo, an area where domestic abuse is more likely due to the tribal nature of the area, shows that physical abuse (battering at least 3 times in the last year) was found in 23% of the investigated women in 2003, 26% amongst married women. Regular abuse (battering at least once weekly) was found in 3.3% of married women, with no regular abused reported by non-married women. The prevalence of physical abuse amongst country residents was 44.3% compared to 18.8% amongst city residents. In most cases (87.4%) the abuse was inflicted by the husband, and in 9.5% of cases, the abuse was inflicted by more than one person. Correlates of physical abuse were women's education, religion, age, marital status, economic status, mental distress, smoking and residence.[54]

Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava

With the Syrian Civil War, the Kurdish populated area in Northern Syria has gained de facto autonomy as the Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava, with the leading political actor being the progressive Democratic Union Party (PYD). Kurdish women have several armed and non-armed organizations in Rojava, and enhancing women's rights is a major focus of the political and societal agenda. Kurdish female fighters in the Women's Protection Units (YPJ) played a key role during the Siege of Kobani and in rescuing Yazidis trapped on Mount Sinjar, and their achievements have attracted international attention as a rare example of strong female achievement in a region in which women are heavily repressed.[55][56][57][58]

The civil laws of Syria are valid in Rojava, as far as they do not conflict with the Constitution of Rojava. One notable example for amendment is personal status law, in Syria still Sharia-based,[15][16] where Rojava introduced civil law and proclaims absolute equality of women under the law and a ban on forced marriage as well as polygamy was introduced,[59] while underage marriage was outlawed as well.[60] For the first time in Syrian history, civil marriage is being allowed and promoted, a significant move towards a secular open society and intermarriage between people of different religious backgrounds.[61]

The legal efforts to reduce cases of underage marriage, polygamy and honor killings are underpinned by comprehensive public awareness campaigns.[62] In every town and village, a women's house is established. These are community centers run by women, providing services to survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault and other forms of harm. These services include counseling, family mediation, legal support, and coordinating safe houses for women and children.[63] Classes on economic independence and social empowerment programs are also held at women's houses.[64]

All administrative organs in Rojava are required to have male and female co-chairs, and forty percent of the members of any governing body in Rojava must be female.[65] An estimated 25 percent of the Asayish police force of the Rojava cantons are women, and joining the Asayish is described in international media as a huge act of personal and societal liberation from an extremely patriarchical background, for ethnic Kurdish and ethnic Arab women alike.[66]

The PYD's political agenda of "trying to break the honor-based religious and tribal rules that confine women" is controversial in conservative quarters of society.[60]

Notable women

- Hadiya Khalaf Abbas, Speaker of the People's Council of Syria (since 2016).

- Asya Abdullah is the co-chairwoman of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the leading political party in Rojava.

- Asma al-Assad, the First Lady of Syria and the wife of the current President Assad

- Najah al-Attar, Vice President of Syria (since 2006).

- Randa Kassis, President of The Astana Platform of the Syrian opposition.

- Suheir Atassi, Vice President of the opposition government.[67]

- Samar Al Dayyoub, literary critic and writer

- Khawla Dunia, opposition activist and poet

- Îlham Ehmed is co-chairwoman of the Syrian Democratic Council.

- Hêvî Îbrahîm is the prime minister of Afrin Canton.

- Samira Khalil, dissident

- Ulfat Idilbi, best-selling Arabic-language novelist.

- Assala Nasri is a musical artist

- Souad Nawfal, opposition activist and schoolteacher.

- Rasha Omran, poet

- Bouthaina Shaaban, Bashar al-Assad's political adviser and previous Minister of Expatriates

- Muna Wassef, theater, television, and film actress.

- Hediya Yousef is an ex-guerilla and co-chairwoman of the executive committee of the Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava.

- Razan Zaitouneh, human rights lawyer and activist.

References

- "Syrian Arab Republic - World Bank Gender Data Portal".

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". archive.ipu.org.

- "World Bank Open Data".

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "Global Gender Gap Report 2021" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- Smith, Bonnie G., ed. (2005). Women's history in global perspective. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780252029905.

- "Syrian Women Making Change". PBS. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Keddie, Nikki R. (2007). Women in the Middle East: past and present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780691128634.

- Tohidi, ed. by Herbert L. Bodman, Nayereh (1998). Women in muslim societies: diversity within unity. Boulder (Colo.): L. Rienner. p. 103. ISBN 9781555875787.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Syria: Extremists Restricting Women's Rights". Human Rights Watch. January 13, 2014.

- "Women in the Arab Armed Forces | The Arab Institute for Women | LAU". The Arab Institute for Women. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- "Women. Life. Freedom. Female fighters of Kurdistan - CNN". www.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- "Female ISIS morality police units terrified and terrorized Mosul". NBC News. 20 November 2016.

- "Syria". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 13. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- "Islamic Family Law: Syria (Syrian Arab Republic)". Law.emory.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- "MENA Gender Equality Profile" (PDF). www.unicef.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- Charles, Lorraine; Kate Denman (October 2012). ""Every knot has someone to undo it." Using the Capabilities Approach as a lens to view the status of women leading up to the Arab Spring in Syria". Journal of International Women's Studies. 13 (5): 195–211.

- Maktabi, Rania (2010-10-01). "Gender, family law and citizenship in Syria". Citizenship Studies. 14 (5): 558. doi:10.1080/13621025.2010.506714. ISSN 1362-1025. S2CID 144409721.

- Maktabi, Rania (2010-10-01). "Gender, family law and citizenship in Syria". Citizenship Studies. 14 (5): 560. doi:10.1080/13621025.2010.506714. ISSN 1362-1025. S2CID 144409721.

- Maktabi, Rania (2010-10-01). "Gender, family law and citizenship in Syria". Citizenship Studies. 14 (5): 567. doi:10.1080/13621025.2010.506714. ISSN 1362-1025. S2CID 144409721.

- "Table 4: Gender Inequality Index". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Pamela, Paxton (2007). Women, Politics, and Power: A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press. pp. 48–49.

- Moubayed, Sami. "A History of Syrian Women". The Washington Post.

- "Syrian Arab Republic". United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "250 New Parliament Members Take Constitutional Oath". Syria Times. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Wright, Robin B. (2008). Dreams and Shadows: the Future of the Middle East. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59420-111-0.

- "Assad's fair ladies: the western-educated women who lulled the world into a false impression of Syria - The Commentator". www.thecommentator.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-14. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- "Syrian Constitutional Committee a 'sign of hope': UN envoy tells Security Council". UN News. 2019-11-22. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- "Names of the members of the Small Body of the Constitutional Committee". www.unog.ch. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- "Labor force, female (% of total labor force) | Data".

- Sly, Liz; Ramadan, Ahmed (2013-01-25). "The all-female militias of Syria". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- Christia, Fotini (2013-03-07). "How Syrian Women Are Fueling the Resistance". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- "Syrian Arab Republic". World Bank Gender Data Portal. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- "Situation for women and girls in Syria worse than ever before as conflict grinds on". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- tsekoio (2020-08-28). "2.12.1. Violence against women and girls: overview". EUROPEAN ASYLUM SUPPORT OFFICE. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Syria's decade of conflict takes massive toll on women and girls". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Syria's decade of conflict takes massive toll on women and girls". www.unfpa.org. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Loss of Access to Education Puts Well-being of Syrian Girls at Risk - Our World". ourworld.unu.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Conflict-related Sexual Violence". IISS. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- Asaf, Yumna (2017). "Syrian Women and the Refugee Crisis: Surviving the Conflict, Building Peace, and Taking New Gender Roles". Social Sciences. 6 (3): 110. doi:10.3390/socsci6030110.

- Kaya, Zeynep (2020-09-02). "Sexual violence, identity and gender: ISIS and the Yezidis". Conflict, Security & Development. 20 (5): 631–652. doi:10.1080/14678802.2020.1820163. ISSN 1467-8802. S2CID 231588827.

- Neurink, Judith (2015). De vrouwen van het kalifaat (in Dutch) (2nd ed.). Belgium: Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas. ISBN 978-94-919-2114-8.

- Bajec, Alessandra. "Yazidi women survivors of ISIL crimes yet to find justice". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

- Sinjab, Lina (12 October 2007). "Honour crime fear of Syria women". BBC News.

- Abu-Odeh, Lama (2010-01-01). "Honor Killings and the Construction of Gender in Arab Societies". Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works.

- Vitoshka, Diana Y. (2010). "The Modern Face of Honor Killing: Factors, Legal Issues, and Policy Recommendations". Berkeley Undergraduate Journal. 22 (2). doi:10.5070/B3222007673.

- Goldstein, Matthew A. (2002). "The Biological Roots of Heat-of-Passion Crimes and Honor Killings". Politics and the Life Sciences. 21 (2): 28–37. ISSN 0730-9384. JSTOR 4236668. PMID 16859346.

- "Child marriage takes a brutal toll on Syrian girls | European Year for Development". europa.eu. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- "Number of Syrian child brides triples since start of conflict". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2015-10-14.

- "Early/Child Marriage in Syrian Refugee Communities" (PDF). July 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Maziak, Wasim; Asfar, Taghrid (April 2003). "Physical Abuse in Low-Income Women in Aleppo, Syria". Health Care for Women International. 24 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1080/07399330390191689. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 12746003. S2CID 35936527.

- "Female Kurdish fighters battling ISIS win Israeli hearts". Rudaw. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "The Fight Against ISIS in Syria And Iraq December 2014 by Itai Anghel". The Israeli Network via YouTube. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Fact 2015 (Uvda) – Israel's leading investigative show". The Israeli Network. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Kurdish female fighters named 'most inspiring women' of 2014". Rudaw. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Gol, Jiyar (2016-09-12). "Kurdish 'Angelina Jolie' devalued by media hype". BBC. Retrieved 2016-09-12.

- "Syrian Kurds tackle conscription, underage marriages and polygamy". ARA News. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- "Syria Kurds challenging traditions, promote civil marriage". ARA News. 2016-02-20. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- "Syrian Kurds give women equal rights, snubbing jihadists". Yahoo News. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Owen, Margaret (2014-02-11). "Gender and justice in an emerging nation: My impressions of Rojava, Syrian Kurdistan". Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Revolution in Rojava transformed the perception of women in the society". Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Tax, Meredith (14 October 2016). "The Rojava Model". Foreign Affairs.

- "Syrian women liberated from Isis are joining the police to protect their city". The Independent. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- "Gulf states back Syria opposition". BBC News. November 13, 2012.

External links

- Survey: Discrimination against Women in Syrian Society (I/II). Awareness of Women Rights and Freedoms, The Day After Association, August 2017 Archived 2018-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Survey: Discrimination Against Women in Syrian Society (II/II): Perception of Domestic Violence, The Day After Association, August 2017 Archived 2018-05-05 at the Wayback Machine