Workflow

A workflow is a generic term for orchestrated and repeatable patterns of activity, enabled by the systematic organization of resources into processes that transform materials, provide services, or process information.[1] It can be depicted as a sequence of operations, the work of a person or group,[2] the work of an organization of staff, or one or more simple or complex mechanisms.

From a more abstract or higher-level perspective, workflow may be considered a view or representation of real work.[3] The flow being described may refer to a document, service, or product that is being transferred from one step to another.

Workflows may be viewed as one fundamental building block to be combined with other parts of an organization's structure such as information technology, teams, projects and hierarchies.[4]

Historical development

The development of the concept of a workflow occurred above a series of loosely defined, overlapping eras.

Beginnings in manufacturing

The modern history of workflows can be traced to Frederick Taylor[5] and Henry Gantt, although the term "workflow" was not in use as such during their lifetimes.[6] One of the earliest instances of the term "work flow" was in a railway engineering journal from 1921.[7]

Taylor and Gantt launched the study of the deliberate, rational organization of work, primarily in the context of manufacturing. This gave rise to time and motion studies.[8] Related concepts include job shops and queuing systems (Markov chains).[9][10]

The 1948 book Cheaper by the Dozen introduced the emerging concepts to the context of family life.

Maturation and growth

The invention of the typewriter and the copier helped spread the study of the rational organization of labor from the manufacturing shop floor to the office. Filing systems and other sophisticated systems for managing physical information flows evolved. Several events likely contributed to the development of formalized information workflows. First, the field of optimization theory matured and developed mathematical optimization techniques. For example, Soviet mathematician and economist Leonid Kantorovich developed the seeds of linear programming in 1939 through efforts to solve a plywood manufacturer's production optimization issues.[11][12] Second, World War II and the Apollo program drove process improvement forward with their demands for the rational organization of work.[13][14][15]

Quality era

In the post-war era, the work of W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran led to a focus on quality, first in Japanese companies, and more globally from the 1980s: there were various movements ranging from total quality management to Six Sigma, and then more qualitative notions of business process re-engineering.[16] This led to more efforts to improve workflows, in knowledge economy sectors as well as in manufacturing. Variable demands on workflows were recognised when the theory of critical paths and moving bottlenecks was considered.[17]

Workflow management

Basu and Kumar note that the term "workflow management" has been used to refer to tasks associated with the flow of information through the value chain rather than the flow of material goods: they characterise the definition, analysis and management of information as "workflow management". They note that workflow can be managed within a single organisation, where distinct roles are allocated to individual resources, and also across multiple organisations or distributed locations, where attention needs to be paid to the interactions between activities which are located at the organizational or locational boundaries. The transmission of information from one organization to another is a critical issue in this inter-organizational context and raises the importance of tasks they describe as "validation", "verification" and "data usage analysis".[18]

Workflow management systems

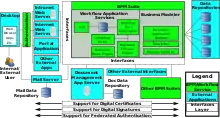

A workflow management system (WfMS) is a software system for setting up, performing, and monitoring a defined sequence of processes and tasks, with the broad goals of increasing productivity, reducing costs, becoming more agile, and improving information exchange within an organization.[19] These systems may be process-centric or data-centric, and they may represent the workflow as graphical maps. A workflow management system may also include an extensible interface so that external software applications can be integrated and provide support for wide area workflows that provide faster response times and improved productivity.[19]

Related concepts

The concept of workflow is closely related to several fields in operations research and other areas that study the nature of work, either quantitatively or qualitatively, such as artificial intelligence (in particular, the sub-discipline of AI planning) and ethnography. The term "workflow" is more commonly used in particular industries, such as in printing or professional domains such as clinical laboratories, where it may have particular specialized meanings.

- Processes: A process is a more general notion than workflow and can apply to, for example, physical or biological processes, whereas a workflow is typically a process or collection of processes described in the context of work, such as all processes occurring in a machine shop.

- Planning and scheduling: A plan is a description of the logically necessary, partially ordered set of activities required to accomplish a specific goal given certain starting conditions. A plan, when augmented with a schedule and resource allocation calculations, completely defines a particular instance of systematic processing in pursuit of a goal. A workflow may be viewed as an often optimal or near-optimal realization of the mechanisms required to execute the same plan repeatedly.[20]

- Flow control: This is a control concept applied to workflows, to distinguish from static control of buffers of material or orders, to mean a more dynamic control of flow speed and flow volumes in motion and in process. Such orientation to dynamic aspects is the basic foundation to prepare for more advanced job shop controls, such as just-in-time or just-in-sequence.

- In-transit visibility: This monitoring concept applies to transported material as well as to work in process or work in progress, i.e., workflows.

Examples

The following examples illustrate the variety of workflows seen in various contexts:

- In machine shops, particularly job shops and flow shops, the flow of a part through the various processing stations is a workflow.

- Insurance claims processing is an example of an information-intensive, document-driven workflow.[21]

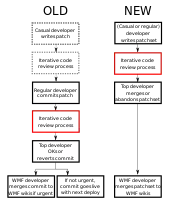

- Wikipedia editing can be modeled as a stochastic workflow.

- The Getting Things Done system is a model of personal workflow management for information workers.

- In software development, support and other industries, the concept of follow-the-sun describes a process of passing unfinished work across time zones.[22]

- In traditional offset and digital printing, the concept of workflow represents the process, people, and usually software technology (RIPs raster image processors or DFE digital front end) controllers that play a part in pre/post processing of print-related files, e.g., PDF pre-flight checking to make certain that fonts are embedded or that the imaging output to plate or digital press will be able to render the document intent properly for the image-output capabilities of the press that will print the final image.

- In scientific experiments, the overall process (tasks and data flow) can be described as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). This DAG is referred to as a workflow, e.g., Brain Imaging workflows.[23][24]

- In healthcare data analysis, a workflow can be identified or used to represent a sequence of steps which compose a complex data analysis.[25][26]

- In service-oriented architectures, an application can be represented through an executable workflow, where different, possibly geographically distributed, service components interact to provide the corresponding functionality under the control of a workflow management system.[27]

- In shared services, an application can be in the practice of developing robotic process automation (called RPA or RPAAI for self-guided RPA 2.0 based on artificial intelligence) which results in the deployment of attended or unattended software agents to an organization's environment. These software agents, or robots, are deployed to perform pre-defined structured and repetitive sets of business tasks or processes. Artificial intelligence software robots are deployed to handle unstructured data sets and are deployed after performing and deploying robotic process automation.

Features and phenomenology

- Modeling: Workflow problems can be modeled and analyzed using graph-based formalisms like Petri nets.

- Measurement: Many of the concepts used to measure scheduling systems in operations research are useful for measuring general workflows. These include throughput, processing time, and other regular metrics.

- Specialized connotations: The term "workflow" has specialized connotations in information technology, document management, and imaging. Since 1993, one trade consortium specifically focused on workflow management and the interoperability of workflow management systems, the Workflow Management Coalition.[28]

- Scientific workflow systems: These found wide acceptance in the fields of bioinformatics and cheminformatics in the early 2000s, when they met the need for multiple interconnected tools that handle multiple data formats and large data quantities. Also, the paradigm of scientific workflows resembles the well-established practice of Perl programming in life science research organizations, making this adoption a natural step towards more structured infrastructure setup.

- Human-machine interaction: Several conceptualizations of mixed-initiative workflows have been studied, particularly in the military, where automated agents play roles just as humans do. For innovative, adaptive, and collaborative human work, the techniques of human interaction management are required.

- Workflow analysis: Workflow systems allow users to develop executable processes with no familiarity with formal programming concepts. Automated workflow analysis techniques can help users analyze the properties of user workflows to conduct verification of certain properties before executing them, e.g., analyzing flow control or data flow. Examples of tools based on formal analysis frameworks have been developed and used for the analysis of scientific workflows and can be extended to the analysis of other types of workflows.[29]

Workflow improvement theories

Several workflow improvement theories have been proposed and implemented in the modern workplace. These include:

- Six Sigma

- Total Quality Management

- Business Process Reengineering

- Lean systems

- Theory of Constraints

Evaluation of resources, both physical and human, is essential to evaluate hand-off points and potential to create smoother transitions between tasks.[30]

Components

A workflow can usually be described using formal or informal flow diagramming techniques, showing directed flows between processing steps. Single processing steps or components of a workflow can basically be defined by three parameters:

- input description: the information, material and energy required to complete the step

- transformation rules: algorithms which may be carried out by people or machines, or both

- output description: the information, material, and energy produced by the step and provided as input to downstream steps

Components can only be plugged together if the output of one previous (set of) component(s) is equal to the mandatory input requirements of the following component(s). Thus, the essential description of a component actually comprises only input and output that are described fully in terms of data types and their meaning (semantics). The algorithms' or rules' descriptions need only be included when there are several alternative ways to transform one type of input into one type of output – possibly with different accuracy, speed, etc.

When the components are non-local services that are invoked remotely via a computer network, such as Web services, additional descriptors (such as QoS and availability) also must be considered.[31]

Applications

Many software systems exist to support workflows in particular domains. Such systems manage tasks such as automatic routing, partially automated processing, and integration between different functional software applications and hardware systems that contribute to the value-addition process underlying the workflow. There are also software suppliers using the technology process driven messaging service based upon three elements:

- Standard Objects

- Workflow Objects

- Workflow

See also

- Bioinformatics workflow management systems

- Business process automation

- Business process management

- Business process modeling

- Computer-supported collaboration

- DRAKON visual language for business process modeling

- Enterprise content management

- Process architecture

- Process mining

- Process-driven application

- Workflow engine

- Workforce modeling

- Business process reengineering

References

- "Business Process Management Center of Excellence Glossary" (PDF). 27 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- See e.g., ISO 12052:2006, ISO.org

- See e.g., ISO/TR 16044:2004, ISO.org

- "Work Flow Automation". Archived from the original on 2013-09-07. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Taylor, 1919

- Ngram Viewer

- Lawrence Saunders; S. R. Blundstone (1921). The Railway Engineer.

- Michael Chatfield; Richard Vangermeersch (5 February 2014). The History of Accounting (RLE Accounting): An International Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-1-134-67545-6.

- Michael L. Pinedo (7 January 2012). Scheduling: Theory, Algorithms, and Systems. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-2361-4.

- Ngram Viewer

- Katseneliboigen, A. (1990). "Chapter 17: Nobel and Lenin Prize Laureate L.V. Kantorovich: The Political Dilemma in Scientific Creativity". The Soviet Union: Empire, Nation, and System. Transaction Publishers. pp. 405–424. ISBN 978-0887383328. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Choudhury, K. (2002). "Chapter 11: Leonid Kantorovich (1912–1986): A Pioneer of the Theory of Optimum Resource Allocation and a Laureate of 1975". In Wahid, A.N.M. (ed.). Frontiers of Economics: Nobel Laureates of the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Press. pp. 93–98. ISBN 978-0313320736. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Smith, J.L. (July 2009). "The History of Modern Quality". PeoriaMagazines.com. Central Illinois Business Publishers, Inc. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Shrader, C.R. (2009). "Chapter 9: ORSA and the Army, 1942–1995 - An Assessment" (PDF). History of Operations Research in the United States Army: Volume III, 1973–1995. Vol. 3. United States Army. pp. 277–288. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Robins Jr., C.H. (2007). "Program and Project Management Improvement Initiatives" (PDF). ASK Magazine. 26: 50–54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-24.

- Michael Hammer; James Champy (13 October 2009). Reengineering the Corporation: Manifesto for Business Revolution, A. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-180864-7.

- Goldratt, Eliyahu M."My saga to improve production." MANAGEMENT TODAY-LONDON- (1996).

- Basu, A. and Kumar, A., Research Commentary: Workflow Management Issues in e-Business, Information Systems Research, volume 13, no. 1, March 2002, pp. 1-14, accessed 1 December 2022

- Elmagarmid, A.; Di, W. (2012). "Chapter 1: Workflow Management: State of the Art Versus State of the Products". In Dogac, A.; Kalinichenko, L.; Özsu, T.; Sheth, A. (ed.). Workflow Management Systems and Interoperability. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–17. ISBN 9783642589089. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Artem M. Chirkin, Sergey V. Kovalchuk (2014). "Towards Better Workflow Execution Time Estimation". IERI Procedia. 10: 216–223. doi:10.1016/j.ieri.2014.09.080.

- Havey, M. (2005). "Chapter 10: Example: Human Workflow in Insurance Claims Processing". Essential Business Process Modeling. O'Reilly Media, Inc. pp. 255–284. ISBN 9780596008437. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Follow-the-sun process

- Brain Image Registration Analysis Workflow for fMRI Studies on Global Grids, Computer.org

- A grid workflow environment for brain imaging analysis on distributed systems, Wiley.com

- Bjørner, Thomas; Schrøder, Morten (23 August 2019). "Advantages and challenges of using mobile ethnography in a hospital case study: WhatsApp as a method to identify perceptions and practices". Qualitative Research in Medicine and Healthcare. 3 (2). doi:10.4081/qrmh.2019.7795.

- Huser, V.; Rasmussen, L. V.; Oberg, R.; Starren, J. B. (2011). "Implementation of workflow engine technology to deliver basic clinical decision support functionality". BMC Medical Research Methodology. 11: 43. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-43. PMC 3079703. PMID 21477364.

- Service-Oriented Architecture and Business Process Choreography in an Order Management Scenario: Rationale, Concepts, Lessons Learned, ACM.org

- "Introduction to the Workflow Management Coalition". Workflow Management Coalition. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Curcin, V.; Ghanem, M.; Guo, Y. (2010). "The design and implementation of a workflow analysis tool" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 368 (1926): 4193–208. Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368.4193C. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0157. PMID 20679131. S2CID 7997426.

- Alvord, Brice (2013). Creating A Performance Based Culture In Your Workplace. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1105576072.

- D. Kyriazis; et al. (June 2008). "An innovative workflow mapping mechanism for Grids in the frame of Quality of Service". Future Generation Computer Systems. 24 (6): 498–511. doi:10.1016/j.future.2007.07.009.

Further reading

- Ryan K. L. Ko, Stephen S. G. Lee, Eng Wah Lee (2009) Business Process Management (BPM) Standards: A Survey. In: Business Process Management Journal, Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Volume 15 Issue 5. ISSN 1463-7154. PDF

- Khalid Belhajjame, Christine Collet, Genoveva Vargas-Solar: A Flexible Workflow Model for Process-Oriented Applications. WISE (1) 2001, IEEE CS, 2001.

- Layna Fischer (ed.): 2007 BPM and Workflow Handbook, Future Strategies Inc., ISBN 978-0-9777527-1-3

- Layna Fischer: Workflow Handbook 2005, Future Strategies, ISBN 0-9703509-8-8

- Layna Fischer: Excellence in Practice, Volume V: Innovation and Excellence in Workflow and Business Process Management, ISBN 0-9703509-5-3

- Thomas L. Friedman: The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-29288-4

- Keith Harrison-Broninski. Human Interactions: The Heart and Soul of Business Process Management. ISBN 0-929652-44-4

- Holly Yu: Content and Work Flow Management for Library Websites: Case Studies, Information Science Publishing, ISBN 1-59140-534-3

- Wil van der Aalst, Kees van Hee: Workflow Management: Models, Methods, and Systems, B&T, ISBN 0-262-72046-9

- Setrag Khoshafian, Marek Buckiewicz: Introduction to Groupware, Workflow and Workgroup Computing, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-02946-7

- Rashid N. Kahn: Understanding Workflow Automation: A Guide to Enhancing Customer Loyalty, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-061918-3

- Dan C. Marinescu: Internet-Based Workflow Management: Towards a Semantic Web, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-43962-2

- Frank Leymann, Dieter Roller: Production Workflow: Concepts and Techniques, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-021753-0

- Michael Jackson, Graham Twaddle: Business Process Implementation: Building Workflow Systems, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-17768-4

- Alec Sharp, Patrick McDermott: Workflow Modeling, Artech House Publishers, ISBN 1-58053-021-4

- Toni Hupp: Designing Work Groups, Jobs, and Work Flow, Pfeiffer & Company, ISBN 0-7879-0063-X

- Gary Poyssick, Steve Hannaford: Workflow Reengineering, Adobe, ISBN 1-56830-265-7

- Dave Chaffey: Groupware, Workflow and Intranets: Reengineering the Enterprise with Collaborative Software, Digital Press, ISBN 1-55558-184-6

- Wolfgang Gruber: Modeling and Transformation of Workflows With Temporal Constraints, IOS Press, ISBN 1-58603-416-2

- Andrzej Cichocki, Marek Rusinkiewicz, Darrell Woelk: Workflow and Process Automation Concepts and Technology, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 0-7923-8099-1

- Alan R. Simon, William Marion: Workgroup Computing: Workflow, Groupware, and Messaging, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-057628-9

- Penny Ann Dolin: Exploring Digital Workflow, Delmar Thomson Learning, ISBN 1-4018-9654-5

- Gary Poyssick: Managing Digital Workflow, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-010911-8

- Frank J. Romano: PDF Printing & Workflow, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-020837-X

- James G. Kobielus: Workflow Strategies, Hungry Minds, ISBN 0-7645-3012-7

- Alan Rickayzen, Jocelyn Dart, Carsten Brennecke: Practical Workflow for SAP, Galileo, ISBN 1-59229-006-X

- Alan Pelz-Sharpe, Angela Ashenden: E-process: Workflow for the E-business, Ovum, ISBN 1-902566-65-3

- Stanislaw Wrycza: Systems Development Methods for Databases, Enterprise Modeling, and Workflow Management, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, ISBN 0-306-46299-0

- Database Support for Workflow Management, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 0-7923-8414-8

- Matthew Searle: Developing With Oracle Workflow

- V. Curcin and M. Ghanem, Scientific workflow systems - can one size fit all? paper in CIBEC'08 comparing scientific workflow systems.