Tripiṭaka tablets at Kuthodaw Pagoda

Stone tablets inscribed with the Tripiṭaka (and other Buddhist texts) stand upright in the grounds of the Kuthodaw Pagoda (kuthodaw means 'royal merit') at the foot of Mandalay Hill in Mandalay, Myanmar (Burma). The work was commissioned by King Mindon as part of his transformation of Mandalay into a royal capital. It was completed in 1868. The text contains the Buddhist canon in the Burmese language.

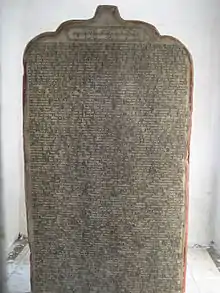

There are 730 tablets and 1,460 pages. Each page is 1.07 metres (3+1⁄2 ft) wide, 1.53 metres (5 ft) tall and 13 centimetres (5+1⁄8 in) thick. Each stone tablet has its own roof and precious gem on top in a small cave-like structure of Sinhalese relic casket type called kyauksa gu (stone inscription cave in Burmese), and they are arranged around a central golden pagoda.[1]

UNESCO inscription

In 2013, UNESCO plaque indicating that the Maha Lawkamarazein or Kuthodaw Inscription Shrines at Kuthodaw Pagoda, which contain the world's largest book in the form of 729 marble slabs on which are inscribed the Tripitaka, were inscribed on to the Memory of the World Register.

Royal merit

The pagoda itself was built as part of the traditional foundations of the new royal city which also included a pitakat taik or library for religious scriptures, but King Mindon wanted to leave a great work of merit for posterity meant to last five millennia after the Gautama Buddha who lived around 500 BC. When the British invaded southern Burma in the mid-19th century, Mindon Min was concerned that Buddhist dhamma (teachings) would also be detrimentally affected in the North where he reigned. As well as organizing the Fifth Buddhist council in 1871, he was responsible for the construction in Mandalay of the world's largest book, consisting of 729 large marble tablets with the Tipitaka Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism inscribed on them in gold. One more was added to record how it all came about, making it 730 stone inscriptions in total.[1]

The marble was quarried from Sagyin Hill 32 miles (51 km) north of Mandalay, and transported by river to the city. Work began on 14 October 1860 in a large shed near Mandalay Palace. The text had been meticulously edited by tiers of senior monks and lay officials consulting the Tipitaka (meaning 'three baskets', namely Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka and Abhidhamma Pitaka) kept in royal libraries in the form of peisa or palm leaf manuscripts. Scribes carefully copied the text on marble for stonemasons. Each stone has 80 to 100 lines of inscription on each side in round Burmese script, chiseled out and originally filled in with gold ink. It took a scribe three days to copy both the obverse and the reverse sides, and a stonemason could finish up to 16 lines a day. All the stones were completed and opened to the public on 4 May 1868.[1]

Assembly and contents

The stones are arranged in neat rows within three enclosures, 42 in the innermost, 168 in the middle and 519 in the outermost enclosure. The caves are numbered starting from the west going clockwise (let ya yit) forming complete rings as follows:[1]

| Enclosure | Cave number | Pitaka |

|---|---|---|

| inner | 1–42 | Vinaya Pitaka |

| middle near | 43–110 | Vinaya |

| middle far | 111–210 | 111 Vinaya, Abhidhamma Pitaka 112–210 |

| outer nearest | 211–319 | Abhidhamma |

| outermost perimeter | 320–465 | Abhidhamma 310–319, Sutta Pitaka 320–417, Samyutta Nikaya 418–465 |

| outermost next in | 466–603 | Samyutta 466–482, Anguttara Nikaya 483–560, Khuddaka Nikaya 561–603 |

| outermost near | 604–729 | Khuddaka |

Thirty years later in 1900, a print copy of the text came out in a set of 38 volumes in Royal Octavo size of about 400 pages each in Great Primer type. The publisher, Philip H. Ripley of Hanthawaddy Press, claimed that his books were "true copies of the Pitaka inscribed on stones by King Mindon". Ripley was a Burmese-born Briton brought up in the royal court of Mandalay by the king and went to school with the royal princes including Thibaw Min, the last king of Burma. At the age of 17 he fled to Rangoon when palace intrigues and a royal massacre broke out after the death of King Mindon, and he had the galley proofs checked against the stones.[1]

Annexation, desecration and restoration

The British later invaded the North, the gems and other valuables were looted, and the buildings and images vandalised by the troops billeted in the temples and pagodas near the walled city and Mandalay Hill. When the troops withdrew from religious sites after a successful petition to Queen Victoria, restoration work began in earnest in 1892 organised by a committee formed by senior monks, members of the royal family and former officers of the king including Atumashi Sayadaw (Abbot of Atumashi Monastery), Kinwon Min Gyi U Kaung (chancellor), Hleithin Atwinwun (minister of the royal fleet), Yaunghwe Saopha Sir Saw Maung (a Shan prince), and Mobyè Sitkè (a general in the royal army). In the tradition of the time, when something needed repair, it was first offered to the relatives of those who had originally made the Dāna (donation) and they came forward and assisted in making repairs. The public was then asked for help, but the full original glory was not achieved.[1]

The gold writing had disappeared from all 729 marble tablets, along with the bells from the hti (umbrella or crown) of each of the small stupas, and they were now marked in black ink, made from shellac, soot from paraffin lamps and straw ash, rather than in gold, and few of the gems still exist. Mobyè Sitkè also asked permission from senior monks to plant star flower trees (Mimusops elengi) between the rows of kyauksa gus.[1] The inscriptions have been re-inked several times since King Thibaw had it done for the second time in gold. The undergrowth amongst the caves was cleared and paved through public donations appealed for in the Ludu Daily in 1968.[1] The words of the Buddha are still preserved there, therefore making it a popular destination for devout Buddhists as well as scholars and tourists.

References

- Ludu Daw Amar - English translation by Prof. Than Tun (1974). The World's Biggest Book. Mandalay: Kyipwayay Press. pp. 22, 9, 14, 50–52, 22, appendix, 53–55, 24–35, 33, 36.