Universal Esperanto Association

The Universal Esperanto Association (Esperanto: Universala Esperanto-Asocio, UEA), also known as the World Esperanto Association, is the largest international organization of Esperanto speakers, with 5501 individual members in 121 countries and 9215 through national associations (in 2015)[1] and in official relations with the United Nations. In addition to individual members, 70 national Esperanto organizations are affiliated with UEA. Its current president is the professor Duncan Charters. The magazine Esperanto is the main organ used by UEA to inform its members about everything happening in the Esperanto community.

Universala Esperanto-Asocio | |

Logo of UEA | |

Individual members by country

1-100 members

101-200 members

201-300 members

301-400 members | |

| Abbreviation | UEA |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1908 |

| Founder | Hector Hodler |

| Purpose | promote the use of Esperanto |

| Headquarters | Central Office |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 51.9138°N 4.4644°E |

Region | World |

Official language | Esperanto |

President | Duncan Charters |

Vice-President | Fernando Maia |

General Director | Martin Schäffer |

Key people | Ivo Lapenna |

Main organ | Central Committee |

| Affiliations | UN, UNESCO |

| Website | UEA.org |

| Part of a series on |

Esperanto flag |

|---|

The UEA was founded in 1908 by the Swiss journalist Hector Hodler and others and is now headquartered in Rotterdam, Netherlands. The organization has an office at the United Nations building in New York City.

Structure and affiliated organizations

According to its 1980 statutes (Statuto de UEA), the Universal Esperanto Association has two kinds of members:

- individual members join the association directly, paying a fee to the Rotterdam headquarters or to the chief delegate in their country. These members receive the UEA Yearbook and receive the UEA services.

- asociaj membroj, those members of the organizations that joined UEA. These members are administered by their respective organizations. It can be a national or a specialist organization. This kind of membership is for the person in question a mere symbolical membership.

The highest organ of UEA, the Komitato, has members (komitatanoj) elected in three different ways:

- An organization sends at least one komitatano, plus one more for every 1,000 national members, to the Komitato. Most national organizations have only one komitatano.

- Per 1,000 individual members, the individual members can choose one member to the Komitato.

- Both previous groups by-elect more komitatanoj, up to one third of their numbers.

The Komitato elects a board, the Estraro. The Estraro installs a general director and sometimes additionally a director. The general director and his staff work at the UEA headquarters, Oficejo de UEA, in Rotterdam.

An individual member can become a delegito, a 'delegate'. This means that he serves as a local contact person for Esperanto and UEA members in his town. A ĉefdelegito (chief delegate) is someone installed also by the UEA headquarters, but with the task to collect the member fees in a given country.

Youth section

TEJO, the World Esperanto Youth Organization, is the youth section of the UEA. Similar to the World Congress, TEJO organizes an International Youth Congress of Esperanto (Internacia Junulara Kongreso) each year in a different location. The IJK is a week-long event of concerts, presentations, excursions attended by hundreds of young people from all over the world.

The youth section has a Komitato and national and specialist affiliated organizations, just as UEA itself. A TEJO volunteer works at the Rotterdam headquarters.

National organizations

The first national Esperanto organization was founded in 1898 in France, originally as a potential international association. In 1903 the second one followed, in Switzerland. Within a couple of years, many of the now still existing national organizations came into existence. Since 1933/1934 they send representatives into the UEA Komitato (a kind of parliament), making it a federation of national organizations. The term in Esperanto was initially mostly Naciaj Societoj (national societies), since 1933 Landaj Asocioj (country associations).

When UEA accepted national organizations in 1933/1934 for the first time, it required them to

- have at least 100 national members,

- be 'organized in an orderly manner',

- be neutral, meaning having no political or religious aims, and being open to all citizens of the country.[2]

Especially the last prerequisite caused serious problems, e.g. to the German national association coming in those months under national socialist rule. Later, for example, the Cuban association was refused because its statutes claimed to respect the leading role of the communist party in Cuba. In 1980, the UEA statutes were altered. Since then, a national organization need not be neutral itself, but must respect the neutrality of UEA.

Specialist organizations

Specialist organizations are similar to the national organizations. They are divided into two groups:

- neutral organizations, that can join UEA in the same way as a national organizations. In Esperanto they are called aliĝintaj fakaj asocioj (affiliated specialist associations). Examples are the Esperanto physicians and the Esperanto teachers.

- other organizations in (official) collaboration with UEA. They do not send representatives to the Komitato but are mentioned in the Yearbook and can have a room at the World Congress. Some of them refuse to be affiliated because of financial reasons, others because they are non-neutral and cannot join UEA. Examples are the Esperanto vegetarians, the Esperanto Catholics and the Esperanto communists.

The youth section TEJO has two affiliated specialist groups, the cyclists and the lovers of rock music.

Activities

Publications

UEA is the publisher of Esperanto, the most important Esperanto periodical. It was started in 1905 by Paul Berthelot, three years before UEA was founded. UEA founder Hector Hodler took it over in 1907 and made it the official UEA magazine in 1908. In 1920 he left the magazine to the association. Since the 1950s it has a paid editor-in-chief. Next to Esperanto, the Yearbook (Jarlibro de UEA) is the oldest continuous publication of the association.

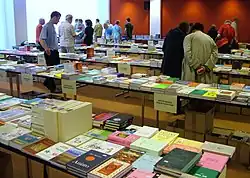

UEA publishes books and has the largest mail-order Esperanto bookstore in the world (with over 6000 books, CDs and other items). It also maintains an information center and an important Esperanto library, called the Hector Hodler Library. The organisation has a network of local representatives from around the world, the Delegita Reto, who are available to provide information about their geographical area or professional field.

Conventions

The yearly World Esperanto Congress (Universala Kongreso de Esperanto), which attracts 1500–3000 people to a different city each year, is held under the direction of UEA. The first congress took place in 1905, and since 1933/1934 the association is in charge of it.

Twice a year, in spring and autumn, UEA headquarters in Rotterdam holds an Open Day.

International organizations

In addition to the UN and UNESCO, UEA also has consultative relations with UNICEF and the Council of Europe, and a general working relationship with the Organization of American States. It works in an official capacity with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) as an A-liaison to ISO/TC37. UEA is active in public information in the European Union and as necessary at other interstate and international organizations and conferences. The organisation is a member of the European Language Council, a common forum of universities and language associations for the awareness of languages and cultures inside and outside the European Union.

In May 2011, UEA officially became an Associate Member of the International Information Centre for Terminology (Infoterm).

Grabowski Prize

The Grabowski Prize is a prize awarded to young authors writing in Esperanto by the Antoni Grabowski Foundation, part of the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA). It is named after Antoni Grabowski, who has been called "the father of Esperanto poetry". The awards for the first three winners are $700, $300 and $150 respectively.[3][4]

Past recipients

Ulrich Becker, a publisher of literature in and about Esperanto and of interlinguistic literature in general was awarded the Grabowski Prize (Premio Grabowski) in 2005 for his achievements in publishing in Esperanto. Among other works, he is the publisher of the three-times-a-year periodical of Esperanto belles-lettres Beletra Almanako.

History

The founding years of the Esperanto movement, 1888–1914

The modern UEA is the result of a decades-long process of several attempts to give the Esperanto movement a proper organization. The first Esperanto associations were local clubs, of which the one in Nuremberg, Germany, is considered the first (1888). From 1898, national Esperanto associations were found in several countries, with the French one being the first. In 1903 followed the Swiss association, in 1904 the British, in 1906 the German and Swedish etc.

The founder of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, wished that an international association came to existence, but the first world congress of 1905 produced only a general manifesto about the essence and neutrality of the movement. The organizing team passed the torch to organizers of a next congress the year after, this eventually created a Konstanta Kongresa Komitato (Permanent Congress Committee). It consisted of two members representing the last congress, two for the current, and two for the following congress.

The Esperantists agreed that the whole movement must support two common international tasks: international documentation, propaganda in countries without movements of their own, lobbying at international organizations, organizing the world congresses, etc. The Esperantists did disagree on which or what organization should be responsible for these tasks, how it should collect the money and how it should decide on spending the money.

In 1906, the French general Hyppolyte Sebert created his Esperantista Centra Oficejo (Central Office of the Esperantists) in Paris. It collected information on the movement and published an Oficiala Gazeto. In spite of this 'official' name, the office was a purely private enterprise of Sebert, but he tried to reach support from the national associations.

One year later, at the Geneva world congress, Zamenhof created a Lingva Komitato (Language Committee, the basis of the later Akademio de Esperanto). It consisted of some eminent speakers from several countries and had to guard the evolution of the language Esperanto. The members of this committee were consequently elected by cooptation.

In 1908, a group of young Esperanto speakers around Hector Hodler founded an international association based on individual, direct membership: Universala Esperanto-Asocio, seated in Geneva. According to Hodler and his followers, an international cause such as Esperanto must be supported by a unitary, truly international association. UEA members should found organizations on national and local levels.

The national (and local) associations saw UEA as a threat, as an undesirable concurrence.[5] They were afraid of a division in the movement between the traditional groups on the one hand and the UEA members on the other. Also, propaganda and lessons were the task of the national associations (often federations of local groups). They did not like the perspective that new Esperantists, created by the traditional groups, would be picked up by UEA.

So the national associations tried to build up an international organizational level by their own. A first attempt were the rajtigitaj delegitoj of the congresses in 1911 and 1912 (not to be confused with the UEA delegitoj); an Internacia Unuiĝo de Esperantistaj Societoj (International Union of Esperanto associations, 1913/1914) was a second attempt. This string in the evolution ceased in 1914 with the breakout of World War I, which forced the movement as a whole to pause many of its activities.

UEA in its first years

The original UEA was purely based on individual membership. The members in a given locality, e.g. a town, were supposed to have UEA member conventions and elect a delegito (plural delegitoj), a delegate. The delegate had the task to collect the member fees and send them to the Geneva headquarters, and he represented his members on the international level. The totality of delegates held referendums, and they elected the Komitato (committee), the highest organ of the association.

The Komitato was a board with initially eight (since 1910: ten) members. It had a president and a vice president. One of the board members was the director, from 1908 to 1920 this was Hector Hodler. The director was the one who installed delegates in towns where there were less than 20 members. These were 94 percent of the delegates, so in certain way UEA was not so much a democracy but ruled by a circular co-option.[6] (Since 1920, the Komitato became larger and a kind of parliament, and a board with the name Estraro was established.)

Hodler was still the owner and publisher of his magazine Esperanto, published every second week. From the beginning, UEA had a Yearbook - Jarlibro - with basic information about the association and with the addresses of the delegates.

Esperanto speakers are divided by different subjects they are interested in. In those early years, there came some specialist organizations into existence, for example the Universala Medicina Esperanto-Asocio of 1908. Hodler tried to give those 'specialists' a home in his UEA. Instead of founding associations of their own, with separate bulletins and conventions, he wanted them to be UEA members and have 'fakoj' (compartments). He also thought of partner organizations, for example hotels who would give a discount to UEA members in change for an advertisement in the UEA Yearbook.

Hodler projected an organization fit to contain ten thousands or hundreds of thousands of members, the so-called esperantianoj (UEA members, in opposition to the simple esperantistoj, Esperanto speakers). In fact, UEA had never more than 10,000 members. The association adopted several new statutes until 1920.

Attempts at organization in the interbellum, 1920–1933

In 1920, the Esperanto movement gathered again since the war, at the Hague congress. The discussions eventually created the so-called Helsinki system, on which UEA and the national associations agreed at the congress of 1922 in the Finnish capital. This system defined the movement to consist of these 'official' entities:

- Universala Esperanto Asocio (UEA), the international members' association in Geneva; it paid contributions to a common budget

- Konstanta Komitato de la Naciaj Societoj (Ko-Ro, Permanent Committee of the National Associations), a newly created organ to represent the national associations; it collected contributions from the national associations for the common budget

- Internacia Centra Komitato de la Esperanto-Movado (ICK, International Central Committee of the Esperanto Movement), a newly created organ elected by UEA and Ko-Ro together; administering the common budget and doing the operational business for the international common tasks, also representing the movement as a whole. It consisted of six persons and had a paid secretary.

- the congress committee, administered and subsidized by the ICK

- the language committee (later the Academy of Esperanto), subsidized by the ICK

This Helsinki system lasted for only a couple of years. The heads of the movement saw that on the world congresses three organs gathered discussing essentially the same subjects: the Komitato of UEA, the Ko-Ro of the national associations and the six members of the ICK. From 1929, they all had a joint gathering called Ĝenerala Estraro (general board). A number of proposals came up in the movement to reform the organization.

But the final blow to the Helsinki system came in 1932 when UEA did not pay its contributions for the common budget, and the same was true for some of the national associations. The British, German and French associations, the largest ones, took up the initiative to found a new organization, Universala Federacio Esperantista (World Federation of Esperantists), as a federation of national associations. This new organization came hardly into existence, because in early 1933 UEA and the national organizations agreed on a complete reform of the movement.

The 'new UEA' and the schism of 1936

In 1933, at the Cologne congress, UEA and the national organizations made UEA the common or umbrella organization of the international Esperanto movement. In 1934 the UEA members accepted new UEA statutes. The 'new UEA', as it was called, was (and still is) a federation of national associations but also of individual members directly administered by UEA.

The highest organ of UEA was the Komitato. It gathered representatives from the national organizations, the numbers depended on the size of the national organization. Other representatives were elected by the delegates, depending on the number of delegates. A third group of representatives was elected by the two first groups, this opened the possibility to include 'experts' who were not linked to a national organization or popular among the delegates. Since 1947, one speaks of the komitatanoj A (from the national organizations), the komitatanoj B (from the delegates, later members) and the komitatanoj C (those by-elected).

As the representatives of the national organizations by far outnumbered the others, it is right to call UEA in essence a federation. But all office holders of UEA had to be individual members, and the core services of the association such as the Yearbook were still reserved to the individual members.

UEA since then is the legal heir of the former Helsinki organizations, such as the International Central Committee. The association since then is also organizing the annual World Congress of Esperanto.

Although in 1933/1934 it first seemed that the transition could happen in harmony, at the 1934 congress in Stockholm some UEA functionaries were not re-elected. In anger, UEA president Eduard Stettler and others resigned. The new board with president Louis Bastien faced a very difficult, if not catastrophal financial situation and decided in early 1936 to leave Geneva for London. In London, the capable activist Cecil C. Goldsmith wanted to become the new director (secretary), and for certain currency reasons UEA could exist significantly more cheaply in Britain than in Switzerland.

Suddenly, a campaign secretly led by Stettler made it the Bastien board impossible to legally move the headquarters away from Switzerland. After discussions taking several months and a referendum, the Bastien board members and the Komitato members left UEA and erected in September 1936 a new association, the Internacia Esperanto-Ligo (IEL). Nearly all national organizations and individual members followed. In Geneva stayed a deserted UEA, in which the old leaders took power again, the so-called Genevan UEA.

UEA after World War II

The international Esperanto movement survived World War II with its IEL headquarters in Heronsgate, a small place in the vicinity of London. Hans Jakob from the Genevan UEA tricked the IEL board into a fusion of IEL and Genevan UEA, lying that the rich Eduard Stettler had left a huge capital to UEA.[7]

Ivo Lapenna, a London law professor originally coming from Croatia, in the 1950s reshaped the association significantly. The office moved from Heronsgate to Rotterdam, the board since then has a general secretary, the Esperanto editor is a paid position. After 1956, the association in 1980 was again (and since then for the last time) given new statutes.

In the decades after the war, the staff grew. Before the war, it was common to have a director with only one or two assistants. After the war, the UEA at times employed ten or more people (e.g. a congress manager, a book seller, a librarian.)

Lapenna introduced a prestige policy,[8] for which he was willing to spend considerable funds. This included signature campaigns for Esperanto and efforts to make UNESCO support Esperanto in a moral way, which Lapenna accomplished in 1954 at the UNESCO conference in Montevideo, Uruguay. This made him famous in Esperanto circles as the hero of Montevideo. After having served for more than 30 years on the board of UEA, Lapenna left the association in 1974 and created a rival organization (Neŭtrala Esperanto-Movado).

During the Cold War, UEA had to deal with the difficulty of having national organizations and individual members in communist countries. Additionally, the work of Esperanto organizations in Western countries was sometimes influenced by the Cold War: In the early 50s, the American Esperanto leader George Allan Connor denounced dissenting members of his national organization as communists. His national organization and he as an individual were eventually thrown out of UEA. The collapse of the Soviet Union and its allied states between 1989 and 1991 completely changed the international situation.

See also

- Category:Presidents of the Universal Esperanto Association

- World Esperanto Youth Organization (TEJO)

- Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, the leftist global Esperanto organization

- World Congress of Esperanto

- Terminologia Esperanto-Centro

References

- La membraro de UEA en 2015, “Esperanto” 1301, april 2016, p. 94

- Sikosek, Marcus: Die neutrale Sprache. Eine politische Geschichte des Esperanto-Weltbundes. Diss. Utrecht 2006. Skonpres, Bydgoszcz 2006, p. 126.

- "Regularo pri la fondaĵo "Antoni Grabowski"". Archived from the original on 2003-06-13.

- Annual Report 2008, Esperantic Studies Foundation

- Sikosek, Marcus: Die neutrale Sprache. Eine politische Geschichte des Esperanto-Weltbundes. Diss. Utrecht 2006. Skonpres, Bydgoszcz 2006, pp. 73-76.

- Sikosek, Marcus: Die neutrale Sprache. Eine politische Geschichte des Esperanto-Weltbundes. Diss. Utrecht 2006. Skonpres, Bydgoszcz 2006, pp. 63/64.

- Sikosek, Marcus: Die neutrale Sprache. Eine politische Geschichte des Esperanto-Weltbundes. Diss. Utrecht 2006. Skonpres, Bydgoszcz 2006, pp. 234, 325.

- Forster, Peter Glover: The Esperanto Movement, Diss. Hull 1977, The Hague et al. 1982 (Hull 1977), pp. 233/234.

Literature

- Forster, Peter Glover: The Esperanto Movement, Diss. Hull 1977, The Hague et al. 1982 (Hull 1977)

- Lins, Ulrich: Utila Estas Aliĝo. Tra la unua jarcento de UEA, Universala Esperanto-Asocio. Rotterdam 2008

- Sikosek, Marcus: Die neutrale Sprache. Eine politische Geschichte des Esperanto-Weltbundas. Diss. Utrecht 2006. Skonpres, Bydgoszcz 2006

External links

- Official website

(in seven languages)

(in seven languages) - Universal Esperanto Association on Twitter

- Universal Esperanto Association on Instagram

- Universal Esperanto Association on Telegram

- UEA's book service

- Terminologia Esperanto-Centro (TEC) UEA's terminology centre