Propaganda in World War I

World War I was the first war in which mass media and propaganda played a significant role in keeping the people at home informed on what occurred at the battlefields.[1] It was also the first war in which governments systematically produced propaganda as a way to target the public and alter their opinion.

According to Eberhard Demm and Christopher H. Sterling:

Propaganda could be used to arouse hatred of the foe, warn of the consequences of defeat, and idealize one's own war aims in order to mobilize a nation, maintain its morale, and make it fight to the end. It could explain setbacks by blaming scapegoats such as war profiteers, hoarders, defeatists, dissenters, pacifists, left-wing socialists, spies, shirkers, strikers, and sometimes enemy aliens so that the public would not question the war itself or the existing social and political system.[2]

Propaganda by all sides presented a highly cleansed, partisan view of fighting. Censorship rules placed strict restrictions on frontline journalism and reportage, a process that continues to affect the historical record — for instance, possibly due to image concerns, there is no known visual evidence of American shotgun use during the war.[3] Propagandists utilized a variety of motifs and ideological underpinnings, such as atrocity propaganda, propaganda dedicated to nationalism and patriotism, and propaganda focused on women.[1][4][5]

Media and censorship

The media was expected to take sides, not to remain neutral, during World War I. When Wilhelm II declared a state of war in Germany on July 31, the commanders of the army corps (German: Stellvertretende Generalkommandos) took control of the administration, including implementing a policy of press censorship, which was carried out under Walter Nicolai.[6]

Censorship regulations were put in place in Berlin, with the War Press Office fully controlled by the Army High Command. Journalists were allowed to report from the front only if they were experienced officers who had "recognized patriotic views". Briefings to the press created a high degree of uniformity in wartime reporting. Contact between journalists and fighting troops was prohibited, and journalists spoke only to high-ranking officers and commanders.[7]

_-_Gassed_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Both sides initially prohibited any photography or filming. The primary visual representation relied on war painting, but the Germans used some heavily-censored filmed newsreels. The French preferred painting over photography, but some parties used photographs to document the aftermath of damage that had been inflicted on cities by artillery. However, photographs of battle scenes were re-enactments by necessity.[7]

When World War I started, the United States had become a leader in the art of filmmaking and the new profession of commercial advertising.[8] Such newly-discovered technologies played an instrumental role in the shaping of the American mind and the altering of public opinion into supporting the war. Every country used careful edited newsreels to combine straight news reports and propaganda.[9][10][11]

By country

Russia

Russian press operating in the Caucasus had been reporting on a "really intolerable situation" in Anatolia since before the formal commencement of hostilities with the Ottoman Empire.

Armenian

Propaganda was one of the tools employed by the Armenians of the Caucasus to advance the Armenian revolutionary movement.[12] The effort to recruit Ottoman Armenians to enlist in the Russian army was supported by Hampartsum Arakelyan, editor of Mshak, a leading Armenian language circular in the Caucasus region.[13] During the Russo-Turkish War of 1878 that set the stage for World War I, Mshak was especially active in publishing pro-Russian propaganda.[14] According to Tasnapetean the intervening years had left the Armenians unprepared to confront the violence of the Armenian Genocide that was unleashed on them in 1915:[15]

...it is evident that after the first few years of elation after the Ottoman Constitution, and despite the gradual deterioration of conditions after 1911, as well as the spread of Pan-Turanian thought and the efforts of the 'Turkji' movement, the Armenians of Turkey―including the executive bodies and ranks of the Dashnaktsutiun―were not psychologically or practically ready in 1915 to resort to general self-defense, let along a general uprising. They had, starting in 1912, elected to again appeal to international diplomacy instead of relying on their own armed struggle.

British

American propaganda

The most influential man behind the propaganda in the United States was President Woodrow Wilson. In his famous January 1918 declaration, he outlined the "Fourteen Points," which he said that the United States would fight to defend.[16] Aside from the restoration of freedom in Europe in countries that were suppressed by the power of Germany, Wilson's Fourteen Points called for transparency regarding discussion of diplomatic matters, the free navigation of the seas in peace and in war, and equal trade conditions among all nations.[16] The Fourteen Points became very popular across Europe and motivated German socialists especially.[17] It served as a blueprint for world peace to be used for peace negotiations after the war.[8] Wilson's points inspired audiences around the world and greatly strengthened the belief that Britain, France, and America were fighting for noble goals.[8]

The 1915 film The German Side of the War was one of the only American films to show the German perspective of the war.[18] At the theater, lines stretched around the block; the screenings were received with such enthusiasm that would-be moviegoers resorted to purchasing tickets from scalpers.[19]

Propaganda made American entry into the war possible, but many propagandists later confessed to fabricating atrocity propaganda. By the 1930s, Americans had grown resistant to atrocity stories. A 1940 study of American public opinion determined that the collective memory of World War I was the primary reason for Allied propaganda during World War II serving only to intensify anti-war sentiment in the United States.[20]

Committee on Public Information

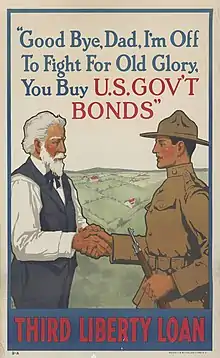

In 1917 Wilson created the Committee on Public Information, which reported directly to him and was essentially a massive generator of propaganda.[8] The Committee on Public Information was responsible for producing films; commissioning posters; publishing numerous books and pamphlets; purchasing advertisements in major newspapers; and recruiting businessmen, preachers, and professors to serve as public speakers in charge of altering public opinion at the communal level.[8] The committee, headed by the former investigative journalist George Creel, emphasized the message that America's involvement in the war was entirely necessary for achieving the salvation of Europe from the German and enemy forces.[8] In his book titled How we Advertised America, Creel states that the committee was called into existence to make World War I a fight that would be a "verdict for mankind."[21] He called the committee a voice that was created to plead the justice of America's cause before the jury of public opinion.[21] Creel also refers to the committee as a "vast enterprise in salesmanship" and "the world's greatest adventure in advertising."[21] The committee's message resonated deep within every American community and served as an organization that was responsible for carrying the full message of American ideals to every corner of the civilized globe.[21] Creel and his committee used every possible mode to get their message across, including printed word, the spoken word, the motion picture, the telegraph, the poster, and the signboard.[21] All forms of communication were put to use to justify the causes that compelled America to take arms.

Creel set out systematically to reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort.[22] The CPI also worked with the post office to censor seditious counter propaganda. Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and to distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men. The CPI created colourful posters that appeared in every store window to catch the attention of passers-by for a few seconds.[23] Cinemas were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during four-minute breaks, which were needed to change reels. They also spoke at churches, lodges, fraternal organizations, labour unions, and even logging camps. Creel boasted that in 18 months, his 75,000 volunteers had delivered over 7.5 million four-minute orations to over 300 million listeners in a nation of 103 million people. The speakers attended training sessions through local universities and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs.[24]

Historians were assigned to write pamphlets and in-depth histories of the causes of the European war.[25][26] After World War I started, both sides of the conflict used propaganda to shape international opinion. Thus, propaganda become a weapon to influence countries.[27]

Italian

Self-justification and assigning blame

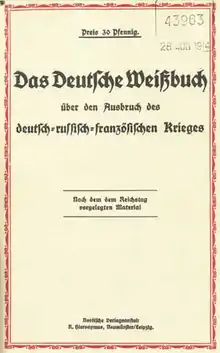

As their armies began to clash, the opposing governments engaged in a media battle attempting to avoid blame for causing the war and casting blame on other countries by the publication of carefully-selected documents, which basically consisted of diplomatic exchanges. The Germans were the first to do so, and other major participants followed within days.[28]

The German White Book[lower-alpha 1] appeared on 4 August 1914. The first such book to come out, it contained 36 documents. In the German White Book, anything that could benefit the Russian position was redacted.[29][lower-alpha 2] Within a week, most other combatant countries had published their own book, each named with a different color name. France held off until 1 December 1914, when it finally published its Yellow Book.[31] Other combatants in the war published similar books: the Blue Book of Britain,[32] the Orange Book of Russia,[32][33] the Yellow Book of France,[34] and the Austro-Hungarian Red Book, the Belgian Grey Book, and the Serbian Blue Book.[35]

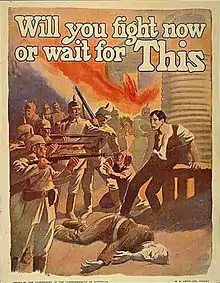

Atrocity propaganda

Atrocity propaganda exploiting sensational stories of rape, mutilation, and wanton murder of prisoners by the Germans filled the Allied press.[36][37] The German and the Austro-Hungarian soldiers were depicted as inhumane savages, and their barbarity was emphasized as a way to provide justification for the war. In 1914, the prominent forensic scientist R.A. Reiss was commissioned by the Serbian prime minister to conduct an investigation on war crimes.[37] It was done as a way to depict the multiple acts of violence that had been committed against civilians by the occupying Austro-Hungarian forces in Serbia in 1914. The reports were written in vivid detail and described individual acts of violence against civilians, soldiers, and prisoners of war.[37] Some of the actions included the use of forbidden weapons, the demolition of ancient libraries and cathedrals, and the rape and the torture of civilians.[37] Graphic illustrations, accompanied by first-hand testimonies that described the crimes as savagely unjust, were compelling reminders to justify the war.[37] Other forms of atrocity propaganda depicted the alternative to war to involve German occupation and domination,[38] which was regarded as unacceptable across the political spectrum. As the Socialist Pioneer of Northampton put it in 1916, there could "be no peace while the frightful menace of world domination by force of German armed might looms about and above us".[38]

The Irish journalist Kevin Myers reported on German atrocities in the war, and he said that in doing so, he drew the ire of Irish nationalists:[39]

I also wrote of German atrocities in Belgium that had aroused the wrath of nationalist Ireland - the sacking of Louvain in particular - and this too was not merely a revelation but a provocation to some. One pugnacious subeditor, a tribally verdant Glasgow-born, Celtic-supporting Ulsterman, came up to me, almost tapping me on the chest. 'That stuff about German atrocities is just British propaganda. British fucking propaganda. There were no German atrocities. I always knew you were a Brit at heart. Now you've proved it!'

Propaganda was used in the war, like other wars, with the truth suffering. Propaganda ensured that the people learned only what their governments wanted them to know. The lengths to which governments would go to try to blacken the enemy's name reached a new level during the war. To ensure that everybody thought as the government wanted, all forms of information were controlled. Newspapers were expected to print what governments wanted readers to read. That would appear to be a form of censorship, but the newspapers of Britain, which were effectively controlled by the media barons of the time, were happy to follow and printed headlines that were designed to stir up emotions, regardless of whether or not they were accurate. The most infamous headlines included "Belgium child's hands cut off by Germans" and "Germans crucify Canadian officer".[5]

Use of patriotism and nationalism

Patriotism and nationalism were two of the most important themes of propaganda.[1] In 1914, the British Army was made up of not only professional soldiers but also volunteers and so the government relied heavily on propaganda as a tool to justify the war to the public eye.[1] It was used to promote recruitment into the armed forces and to convince civilians that if they joined, their sacrifices would be rewarded.[1] One of the most impressionable images of the war was the "Your Country Needs You" poster, a distinctive recruitment poster of Lord Kitchener (similar to the later Uncle Sam poster) pointing at his British audience to convince it to join the war effort.[1] Another message that was deeply embedded in national sentiment the religious symbolism of St George, who was shown slaying a dragon, which represented the German forces.[1] Images of enthusiastic patriotism seemed to encapsulate the tragedy of the European and imperial populations.[38] Such images conjured up feelings of required patriotism and activism among those who were influenced.[38]

The German Kaiser often appeared in Allied propaganda. His pre-1898 image of a gallant Victorian gentleman was long gone and was replaced by a dangerous troublemaker in the pre-1914 era. During the war, he became the personified image of German aggression; by 1919, the British press was demanding his execution. He died in exile in 1941, and his former enemies had moderated their criticism toward him and instead turned the hatred against Hitler.[40]

Use as weapon

The major foreign ministries prepared propaganda designed to reach public opinion and elite opinion in other countries, especially the neutral powers. For example, the British were especially effective in turning American opinion against Germany before 1917.[41][42] Propaganda thus became an integral part of the diplomatic history of World War I and was designed to build support for the cause or to undermine support for the enemy. Eberhard Demm and Christopher H. Sterling, state:

- Propaganda could also win over neutral states by encouraging friendly elements and local warmongers, or, at a minimum, keep neutrals out of the war by fostering non-intervention or pacifist views.... It could help retain allies, break up enemy alliances, and prepare exhausted or dissatisfied nations to defect or make a separate piece.[43]

Nonmilitary propaganda into neutral countries war was designed to build support for the cause or to undermine support for the enemy.[44] Wartime diplomacy focused on five issues: propaganda campaigns to shape news reports and commentary; defining and redefining the war goals, which became harsher as the war went on; luring neutral nations (Italy, the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria and Romania) into the coalition by offering slices of enemy territory; and encouragement by the Allies of nationalistic minority movements within the Central Powers, especially among Czechs, Poles, and Arabs.

In addition, multiple peace proposals came from neutrals and from both sides although none of them progressed very far. Some were neutral efforts to end the horrors. Others were propaganda ploys to show one side as being reasonable and the other as obstinate.[45]

As soon as the war began, Britain cut Germany's undersea communication cables as a way to ensure that the Allies had a monopoly on the most expedient means of transmitting news from Europe to press outlets in the United States.[46] That was a way to influence reporting of the war around the world and to gain sympathy and support from the other nations.[46] In 1914, a secret British organization, Wellington House, was set up and called for journalists and newspaper editors to write articles that sympathised with Britain as a way to counter statements that were made by the enemy.[46] Wellington House implemented the action not only through favourable reports in the press of neutral countries but also by publishing its own newspapers, which were circulated around the globe.[46] Wellington House was so secret that much of Parliament was in the dark. Wellington House had a staff of 54 people, which made it the largest British foreign propaganda organisation.[47] From the Wellington House came to the publication The War Pictorial, which by December 1916 had reached a circulation of 500,000, covering 11 languages. The War Pictorial was deemed to have such a powerful effect on different masses that it could turn countries like China against Germany.[46]

Women

Propaganda and its ideological impacts on women and family life in the era differed by country. British propaganda often promoted the idea that women and their families were threatened by the enemy, particularly the German Army.[48] British propaganda played on the fears of the country's citizens by depicting the German Army as a ravenous force that horrified towns and cities, raped women and tore families apart.[48] The terror ensued by the gendered propaganda influenced Britain's war policies, and violence against the domestic sphere in wartime became seen as an inexcusable war crime.[48]

In the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and other countries, women were encouraged to enter the workforce since the number of men kept shrinking during the war.[49] The Ottoman government already had a system that incorporated the participation of women in governmental committees that had established in 1912 and 1913.[49] Thus, when the war began, the government spread patriotic propaganda to women all over the empire through the women's committees.[49] Propaganda encouraged women to enter the workforce, both to support the Empire and to become self-sufficient by state-sanctioned work that was specified for women.[49]

American war propaganda often featured images of women but typically reflected traditional gender norms.[4] While there was increasingly a call to employ women to replace the men who were at war, American propaganda also emphasized sexual morality.[50] Women's clubs often produced attitudes against gambling and prostitution.[50]

In wartime fiction published by magazines like McClure's, female characters were cast as either virtuous self-sacrificing homemakers sending the men to war or unethical and selfish women who were usually drunk and too wealthy to be restrained by social mores. McClure's Win-the-War Magazine included contributions from authors Porter Emerson Browne and Dana Gatlin, recognized by scholars for their sentimental style of writing propaganda fiction employing stereotyped female characters. Browne once said of melodramatic writing: "Don't be afraid of seasoning too highly, nor of cooking too fiercely. You can't do it." In Mary and Marie, Browne accuses Mary (and, by extension, her country) of sitting "idly by, selfish, self-satisfied... squandering vacuously in self-pander [all] her riches of honor and courage and dignity", and Marie's country "went to war to save her gentle soul from dishonor". The virtuous Marie is revered and saintly even though she has been savagely raped by the Germans and left for dead.[51]

The "immoral woman" archetype also appears in Dana Gatlin's New York Stuff. Gatlin describes New York as "too engrossed with her materialistic provender, the things which can be judged in terms of dollars and cents, which can be bought and sold; the things which, in the destroyed or partially destroyed cities of Europe, the very hand of distraction has proved to be but ephemeral baubles after all". Even married women are a threat lurking within the Gemeinschaft when they act in ways that undermine that family structure. The "dangerous married woman" stereotype shows a woman trying to corrupt an innocent girl, a stereotype that appears in other novels. Stereotypes of corrupted femininity are presented in the wartime propaganda as a source of evil. Self-sacrificing women who hold down the home front and send "their men" to war are portrayed as the model for the dutiful wartime home maker and the heart of the Gemeinschaft.[51]

See also

- Home front during World War I

- British propaganda during World War I

- Wellington House, the common name for Britain's War Propaganda Bureau

- History of the United Kingdom during World War I#Propaganda

- Italian propaganda during World War I

- Opposition to World War I

- Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War

- Causes of World War I

References

- Notes

- The German title of the White Book was Das Deutsche Weißbuch über den Ausbruch des deutsch-russisch-französischen Krieges ("The German White Book about the Outbreak of the German-Russian-French War".

- The German White Book was translated and published in English the same year.[30]

- Citations

- Welch, David. "Propaganda for patriotism and nationalism". British Library. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Eberhard Demm and Christopher H. Sterling, "Propaganda" in Spencer C. Tucker and Priscilla Roberts, eds. The Encyclopedia of World War I : A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO 2005) 3:941.

- Tom Laemlein (January 23, 2018). "The Trouble with Trench Guns". American Rifleman. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- Dumenil, L. (2002-10-01). "American Women and the Great War". OAH Magazine of History. 17 (1): 35–37. doi:10.1093/maghis/17.1.35. ISSN 0882-228X.

- Trueman, Chris. "Propaganda and World War One". History Learning Site.

- Demm, Eberhard (1993). "Propaganda and Caricature in the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. 28: 163–192. doi:10.1177/002200949302800109. S2CID 159762267.

- Selling War: The Role of Mass Media in Hostile Conflicts From World War I to the 'War on Terror'. University of Chicago Press. p. 29.

- Messinger, Gary (January 1, 1992). British Propaganda and the State in the First World War. Manchester University Press. pp. 20–30.

- Laurent Véray, "1914–1918, the first media war of the twentieth century: The example of French newsreels." Film History: An International Journal 22.4 (2010): 408-425 online.

- Larry Wayne Ward, The motion picture goes to war: The US government film effort during World War I (UMI Research Press, 1985).

- Wolfgang Miihl-Benninghaus, "Newsreel Images of the Military and War, 1914-1918" in A Second Life: German Cinema's First Decades ed. by Thomas Elsaesser, (1996) online.

- Tasnapetean, Hrach (1990). History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaktsutiun. Michigan University. p. 154.

- McMeekin, Sean (2011). The Russian Origins of the First World War. Harvard University Press. p. 23.

- Nalbandian, Louise (1963). The Armenian Revolutionary Movement. University of California Press. p. 55.

- Tasnapetean, Hrach (1990). History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaktsutiun. Michigan University. p. 111.

- Wilson, Woodrow (January 8, 1918). "President Wilson's Message to Congress". Records of the United States Senate.

- John L. Snell, "Wilson's Peace Program and German Socialism, January–March 1918." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 38.2 (1951): 187-214 online.

- Ward, Larry Ward (1981). The Motion Picture Goes to War: A Political History of the U.S. Government's Film Effort in the World War, 1914-1918. University of Iowa.

- Isenberg, Michael (1973). War on Film: The American Cinema and World War I, 1914-1941. University of Colorado.

- Horten, Gerd (2002). Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda during World War II. University of California Press. p. 16.

- Creel, George (1920). How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information that Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe. Harper and Brothers.

- Stephen Vaughn, Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information (1980). online

- Katherine H. Adams, Progressive Politics and the Training of America's Persuaders (1999)

- Lisa Mastrangelo, "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12#4 (2009): 607-633.

- George T. Blakey, Historians on the Homefront: American Propagandists for the Great War (1970)

- Committee on public information, Complete Report of the Committee on Public Information: 1917, 1918, 1919 (1920) online free

- "Propaganda as a weapon? Influencing international opinion". The British Library. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- Hartwig, Matthias (12 May 2014). "Colour books". In Bernhardt, Rudolf; Bindschedler, Rudolf; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Vol. 9 International Relations and Legal Cooperation in General Diplomacy and Consular Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-4832-5699-3. OCLC 769268852. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Kempe, Hans (2008). Der Vertrag von Versailles und seine Folgen: Propagandakrieg gegen Deutschland [The Treaty of Versailles and its Consequences: Propaganda War against Germany]. Vaterländischen Schriften (in German). Vol. 7 Kriegschuldlüge 1919 [War Guilt Lies 1919]. Mannheim: Reinhard Welz Vermittler Verlag e.K. pp. 238–257 (vol. 7 p.19). ISBN 978-3-938622-16-2. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Germany. Auswärtiges Amt (1914). The German White-book: Authorized Translation. Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the War, with Supplements. Liebheit & Thiesen. OCLC 1158533. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E. (1 April 1937). "France and the Outbreak of the World War". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. 26 (3). Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "German White Book". United Kingdom: The National Archives. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Kempe 2008, vol.7, p.18.

- Kempe 2008, vol.7, p.19.

- Beer, Max (1915). "Das Regenbogen-Buch": deutsches Wiessbuch, österreichisch-ungarisches Rotbuch, englisches Blaubuch, französisches Gelbbuch, russisches Orangebuch, serbisches Blaubuch und belgisches Graubuch, die europäischen Kriegsverhandlungen [The Rainbow Book: German White Book, Austrian-Hungarian Red Book, English Blue Book, French Yellow Book, Russian Orange Book, Serbian Blue Book and Belgian Grey Book, the European war negotiations]. Bern: F. Wyss. pp. 16–. OCLC 9427935. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Nicoletta F. Gullace, "Sexual violence and family honor: British propaganda and international law during the First World War," American Historical Review (1997) 102#3 714–747.

- Fox, Jo. "Atrocity Propaganda". British Library. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Purseigle, Pierre. "Inside the First World War". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Myers, Kevin (11 September 2020). Burning Heresies: A Memoir of a Life in Conflict, 1979-2020. Merrion Press. ISBN 9781785372636.

- Lothar Reinermann, "Fleet Street and the Kaiser: British public opinion and Wilhelm II." German History 26.4 (2008): 469-485.

- M. L. Sanders, "Wellington House and British propaganda during the First World War", The Historical Journal (1975) 18#1: 119–146.

- Cedric C. Cummins, Indiana Public Opinion and the World War 1914-1917 (1945) pp 22–24.

- Demm and Sterling in The Encyclopedia of World War I (2005) 3:941.

- Edward Corse, A battle for neutral Europe: British cultural propaganda during the Second World War (London: A&C Black, 2012).

- See Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Official Statements of War Aims and Peace Proposals: December 1916 to November 1918, edited by James Brown Scott. (1921) 515 pp.online free

- Cooke, Ian. "Propaganda as a weapon? Influencing international opinion". British Library. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Epstein, Jonathan. "German and English Propaganda in World War I". bobrowen.com. NYMAS. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Gullace, Nicoletta F. (June 1997). "Sexual Violence and Family Honor: British Propaganda and International Law during the First World War". The American Historical Review. 102 (3): 714–747. doi:10.2307/2171507. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2171507.

- "Women's Mobilization for War (Ottoman Empire/ Middle East) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- Courtney Q. Shah (2010). ""Against Their Own Weakness": Policing Sexuality and Women in San Antonio, Texas, during World War I". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 19 (3): 458–482. doi:10.1353/sex.2010.0001. ISSN 1535-3605. PMID 21110465. S2CID 12568142.

- Kingsbury, Celia Malone (2010). For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 68–71.

Further reading

- Cornwall, Mark. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds. London: Macmillan, 2000.

- Cull, Nicholas J., David Culbert, et al. eds. Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present (2003) online review

- Cummins, Cedric C. Indiana Public Opinion and the World War 1914-1917 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1945).

- DeBauche, L.M. Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997).

- Demm, Eberhard. Censorship and Propaganda in World War I: A Comprehensive History (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019) online

- Goebel, Stefan. "When Propaganda (Studies) Began," Munitions of the Mind (Centre for the History of War, Media and Society. 2016) online

- Gullace, Nicoletta F. "Allied Propaganda and World War I: Interwar Legacies, Media Studies, and the Politics of War Guilt" History Compass (Sept 2011) 9#9 pp 686–700

- Gullace, Nicoletta F. "Sexual violence and family honor: British propaganda and international law during the First World War," American Historical Review (1997) 102#3 714–747. online

- Hamilton, Keith (2007-02-22). "Falsifying the Record: Entente Diplomacy and the Preparation of the Blue and Yellow Books on the War Crisis of 1914". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 18 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1080/09592290601163019. ISSN 0959-2296. OCLC 4650908601. S2CID 154198441.

- Haste, Cate (1977), Keep the Home Fires Burning: Propaganda in the First World War, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Horne, John; Kramer, Alan (2001), German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2010) chapters 16, 19, 22, 23, 24. online

- Kaminski, Joseph Jon. "World War I and Propaganda Poster Art: Comparing the United States and German Cases." Epiphany Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies 2 (2014): 64-81. online

- Knightley, Phillip (2002), The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Kosovo, Johns Hopkins UP, ISBN 978-0-8018-6951-8

- Lasswell, Harold. Propaganda Technique In The World War (1927) online

- Messinger, Gary S. (1992), British Propaganda and the State in the First World War, New York

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mock, James R., and Cedric Larson. Words that won the war: the story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917-1919 (1939) online

- Paddock, Troy R. E. World War I and Propaganda. (2014)

- Ponsonby, Arthur (1928), Falsehood in War-Time: Propaganda Lies of the First World War, London: George Allen and Unwin

- Sanders, M. L. (1975), "Wellington House and British propaganda during the First World War", The Historical Journal, 18 (1): 119–146, doi:10.1017/S0018246X00008700, JSTOR 2638471, S2CID 159847468

- Sanders, M. L.; Taylor, Philip M. (1982), British Propaganda During the First World War, 1914–18, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Zachary. Age of Fear: Othering and American Identity during World War I. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.

- Stanley, P. What Did You do in the War, Daddy? A Visual History of Propaganda Posters New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Thompson, J. Lee. "‘To Tell the People of America the Truth’: Lord Northcliffe in the US, Unofficial British Propaganda, June–November 1917." Journal of Contemporary History 34.2 (1999): 243–262.

- Thompson, J. Lee. Politicians, the Press, and Propaganda: Lord Northcliffe and the Great War, 1914-1919 (2000) in Britain

- Tunc, T. E. "Less Sugar, More Warships: Food as American Propaganda in the First World War" War in History (2012). 19#2 pp: 193-216.

- Vaughn, Stephen. Holding fast the inner lines : democracy, nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information (1980) online

- Welch, David (2003), "Fakes", in Nicholas J. Cull, David H. Culbert and David Welch (ed.), Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present, ABC-CLIO, pp. 123–124, ISBN 978-1-57607-820-4

- Welch, David. Germany and Propaganda in World War I: Pacifism, Mobilization and Total War London: IB Tauris, 2014.

- Zeman, Z. A. B. Selling the war: Art and propaganda in World War II (1978) online

External links

![]() Media related to World War I propaganda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to World War I propaganda at Wikimedia Commons

- Badsey, Stephen: Propaganda: Media in War Politics, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Demm, Eberhard: Propaganda at Home and Abroad, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Brendel, Steffen: Othering/Atrocity Propaganda , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Aulich, James: Graphic Arts and Advertising as War Propaganda, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Records of World War I propaganda posters are held by Simon Fraser University's Special Collections and Rare Books

- Cooke Ian: Propaganda as a Weapon? Influencing International Opinion., The British Library, The British Library, 23 Jan. 2014,

- Cooke Ian: Propaganda in World War I: Means, Impacts and Legacies., Fair Observer, 9 Oct. 2014, .

- Ther Vanessa: Propaganda at Home (Germany), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- “World War 1 Propaganda Posters.” Examples of Propaganda from WW1 | American WW1 Propaganda Posters Page 5,

- “World War 1 Propaganda Posters.” Examples of Propaganda from WW1 | German WW1 Propaganda Posters,

- Canadian Posters from the First World War, online exhibit on Archives of Ontario website

- The French Woman in War-Time

- Stage Women's War Relief

- Women are Working Day and Night to Win the War

- Joan of Arc Saved France. Women of America, Save Your Country--Buy War Savings Stamps

- John P. Cushing (AC 1882) World War I Poster Collection at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections