Sloop John B

"Sloop John B" (originally published as "The John B. Sails") is a Bahamian folk song from Nassau. A transcription was published in 1916 by Richard Le Gallienne, and Carl Sandburg included a version in his The American Songbag in 1927. There have been many recordings of the song since the early 1950s, with variant titles including "I Want to Go Home" and "Wreck of the John B".

| The John B. Sails | |

|---|---|

| Traditional song | |

Sailboats off Nassau, Bahama Islands, c. 1900. | |

| Other name |

|

| Style | Folk |

| Language | English |

| Published | 1916 |

In 1966, American rock band the Beach Boys recorded a folk rock adaptation that was produced and arranged by Brian Wilson and released as the second single from their album Pet Sounds. The record peaked at number three in the U.S., number two in the UK, and topped the charts in several other countries. It was innovative for containing an elaborate a cappella vocal section not found in other pop music of the era, and it remains one of the group's biggest hits.[1]

In 2011, the Beach Boys' version of "Sloop John B" was ranked number 276 on Rolling Stone's list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[2]

Earliest publications

"The John B. Sails" was transcribed by Richard Le Gallienne, with five verses and the chorus published in his article "Coral Islands and Mangrove-Trees" in the December 1916 issue of Harper’s Monthly Magazine.[3] Gallienne published the first two verses and chorus in his 1917 novel Pieces of Eight.[4] The lyrics describe a disastrous voyage on a sloop, with the vessel plagued by drunkenness and arrests and a pig eating the narrator's food.

Carl Sandburg included the first three verses and chorus of "The John B. Sails" in his 1927 collection The American Songbag. He states that he collected it from John T. McCutcheon, a political cartoonist from Chicago. McCutcheon told him:

Time and usage have given this song almost the dignity of a national anthem around Nassau. The weathered ribs of the historic craft lie imbedded in the sand at Governor's Harbor, whence an expedition, especially sent up for the purpose in 1926, extracted a knee of horseflesh and a ring-bolt. These relics are now preserved and built into the Watch Tower, designed by Mr. Howard Shaw and built on our southern coast a couple of points east by north of the star Canopus.

The Beach Boys version

| "Sloop John B" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

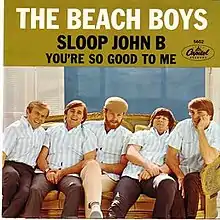

U.S. picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beach Boys | ||||

| from the album Pet Sounds | ||||

| B-side | "You're So Good to Me" | |||

| Released | March 21, 1966 (US) April 15, 1966 (UK) | |||

| Recorded | July 12 – December 29, 1965 | |||

| Studio | United Western Recorders, Hollywood | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:59 | |||

| Label | Capitol | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional, arranged by Brian Wilson | |||

| Producer(s) | Brian Wilson | |||

| The Beach Boys singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Sloop John B" on YouTube | ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

| ||||

Arrangement

The Kingston Trio's 1958 recording of "The John B. Sails" was recorded under the title "The Wreck of the John B."[9] It was the direct influence on the Beach Boys' version. The Beach Boys' Al Jardine was a keen folk music fan, and he suggested to Brian Wilson that the Beach Boys should record the song. As Jardine explains:

Brian was at the piano. I asked him if I could sit down and show him something. I laid out the chord pattern for 'Sloop John B.' I said, 'Remember this song?' I played it. He said, 'I'm not a big fan of the Kingston Trio.' He wasn't into folk music. But I didn't give up on the idea. So what I did was to sit down and play it for him in the Beach Boys idiom. I figured if I gave it to him in the right light, he might end up believing in it. So I modified the chord changes so it would be a little more interesting. The original song is basically a three-chord song, and I knew that wouldn't fly.

Jardine updated the chord progression by having the subdominant (D♭ major) move to its relative minor (B♭ minor) before returning to the tonic (A♭ major), thus altering a portion of the song's progression from IV — I to IV — ii — I. This device is heard immediately after the lyric "into a fight" and "leave me alone".

So I put some minor changes in there, and it stretched out the possibilities from a vocal point of view. Anyway, I played it, walked away from the piano and we went back to work. The very next day, I got a phone call to come down to the studio. Brian played the song for me, and I was blown away. The idea stage to the completed track took less than 24 hours.[10]

Wilson elected to change some lyrics: "this is the worst trip since I've been born" to "this is the worst trip I've ever been on", "I feel so break up" to "I feel so broke up", and "broke up the people's trunk" to "broke in the captain's trunk". The first lyric change has been suggested by some to be a subtle nod to the 1960s psychedelia subculture.[2][11][12]

Recording

The instrumental section of the song was recorded on July 12, 1965, at United Western Recorders, Hollywood, California, the session being engineered by Chuck Britz and produced by Brian Wilson. The master take of the instrumental backing took fourteen takes to achieve. Wilson's arrangement blended rock and marching band instrumentation with the use of flutes, glockenspiel, baritone saxophone, bass, guitar, and drums.[13]

The vocal tracks were recorded over two sessions. The first was recorded on December 22, 1965, at Western Recorders, produced by Wilson. The second, on December 29, added a new lead vocal and Billy Strange's 12-string electric guitar part. Jardine explained that Wilson "lined us up one at a time to try out for the lead vocal. I had naturally assumed I would sing the lead, since I had brought in the arrangement. It was like interviewing for a job. Pretty funny. He didn't like any of us. My vocal had a much more mellow approach because I was bringing it from the folk idiom. For the radio, we needed a more rock approach. Wilson and Mike [Love] ended up singing it."[14] On the final recording, Brian Wilson sang the first and third verses and Mike Love sang the second.

Kent Hartman, in his book The Wrecking Crew, described Billy Strange's contribution to the song. Brian Wilson called Strange into the studio one Sunday, played him the rough recording, and told him he needed an electric twelve-string guitar solo in the middle of the track. When Strange replied that he did not own a twelve string, Wilson responded by calling Glenn Wallichs, the head of Capitol Records and owner of Wallichs Music City. A Fender Electric XII and Twin Reverb amplifier were quickly delivered (despite the shop they were ordered from being closed on Sundays), and Strange recorded the guitar part in one take. Wilson then gave Strange $2,000 to cover the cost of the equipment.[15]

Single release

A music video set to "Sloop John B" was filmed for the UK's Top of the Pops, directed by newly employed band publicist Derek Taylor. It was filmed at Brian's Laurel Way home with Dennis Wilson acting as cameraman.[16]

The single, backed with the B-side "You're So Good to Me", was released on March 21, 1966. It entered the Billboard Hot 100 chart on April 2, and peaked at No. 3 on May 7, remaining on the chart, in total, for 11 weeks. It charted highly throughout the world, remaining as one of the Beach Boys' most popular and memorable hits. It was No. 1 in Germany, Austria, and Norway—all for five weeks each—as well as Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, South Africa, and New Zealand. It placed No. 2 in the UK, Ireland (where it was the group's highest charting single), Canada, and in Record World. It was the fastest Beach Boys seller to date, moving more than half a million copies in less than two weeks after release.[17] It had a three-week stay at number 1 in the Netherlands, making it the "Hit of the Year".[18]

Cash Box described the single as a "topflight adaptation" that treats "the folk oldie in a rhythmic, effectively-building warm-hearted rousing style."[19] Record World said that "The Beach Boys have taken a tune from the folk books and given it an intriguing rock backing."[20]

Other releases

In 1968, the recording's instrumental was released on Stack-O-Tracks. Along with sessions highlights, the box set The Pet Sounds Sessions includes two alternate takes, one with Carl Wilson singing lead on the first verse, and one with Brian singing all parts.

In 2011, the song was sung by Fisherman's Friends at Cambridge Folk Festival.[21] and released on Suck'em and Sea.[22] It was featured in the compilation album Cambridge Folk Festival 2011 [23] In 2016, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Pet Sounds, Brian Wilson and his touring band (including Al Jardine) performed Sloop John B live at Capitol Studios.[24]

In 2021, another UK based group, Isle 'Ave A Shanty sang the song at the 2021 Harwich Sea Shanty Festival and included the song on their 2022 debut album Swinging the Lamp.[25][26]

Personnel

Per band archivist Craig Slowinski.[27]

The Beach Boys

- Bruce Johnston — backing vocals

- Mike Love – lead and backing vocals

- Al Jardine – backing vocals

- Brian Wilson – lead and backing vocals

- Carl Wilson – backing vocals

- Dennis Wilson – backing vocals

Additional musicians and production staff

- Hal Blaine – drums

- Chuck Britz – engineer

- Frank Capp – glockenspiel

- Al Casey – acoustic rhythm guitar

- Jerry Cole – 12-string lead guitar

- Steve Douglas – temple blocks

- Carol Kaye – electric bass

- Al De Lory – tack piano

- Jay Migliori – flute

- Jim Horn – flute

- Jack Nimitz – bass saxophone

- Lyle Ritz – string bass

- Billy Strange – 12-string lead guitar, overdubbed 12-string lead guitars

- Tony (surname unknown) – tambourine

In popular culture

- In many Jewish communities, the Shabbat table song "D'ror Yikra" is sometimes sung to the tune of "Sloop John B" because of its similar meter.[28]

English football

It has been popular amongst English football fans since the mid-2000s when Liverpool adapted the song to sing about their 2005 Champions League final triumph in Istanbul. It was subsequently adopted by the supporters of English non-league team F.C. United of Manchester as a club anthem in 2007.[29][30]

Since then more high-profile teams have followed suit, usually with different lyrics for their own teams, including Watford, with Newcastle, Blackpool, Middlesbrough and Hull also adopting the song as their own. It was sung by Phil Brown, the manager of Hull City FC, shortly after Hull had avoided relegation from the Premier League in 2009.

Scottish football

The melody of "Sloop John B" has been used as the basis for the "Famine Song", a sectarian anti-Irish Catholic song which refers to Irish migration to Great Britain in the context of the Great Irish Famine and contains the line "the famine's over, why don't you go home?". The song has been sung by fans of Rangers F.C. in reference to rival club Celtic F.C., which was established by Irish Catholic migrants in Glasgow and retains a large Irish supporter base.[31][32] The song was first sung publicly by Rangers fans at a match at Celtic Park in April 2008.[33] Rangers have repeatedly asked their fans not to sing the song. In 2009 Scotland's Justiciary Appeal Court ruled that the song was racist, with judge Lord Carloway stating that its lyrics "are racist in calling upon people native to Scotland to leave the country because of their racial origins".[32]

List of recordings

All versions titled "Sloop John B", except where noted.

- 1950 – The Weavers - "(The Wreck of the) John B" [34]

- 1952 – Blind Blake (Blake Alphonso Higgs) – "John B. Sails"

- 1958 – The Kingston Trio – "(The Wreck of the) John B"

- 1959 – Johnny Cash – "I Want To Go Home"

1960s

- 1960 – Bud & Travis (Bud and Travis in Concert 1960)

- 1960 – Lonnie Donegan – "I Wanna Go Home (Wreck of the John B)" UK No. 5[35]

- 1960 – Jimmie Rodgers - "Wreck of the John B" US No. 64[36] Can. No. 1 (3 weeks)[37]

- 1961 – Jerry Butler - "John B" from LP "Folk Songs" (Vee-Jay records)

- 1962 – Arthur Lyman Group - "(The Sloop) John B."

- 1962 – Dick Dale and his Del-Tones

- 1962 – Keith and Enid - "Wreck of the John B"

- 1963 – The Brothers Four - "The John B. Sails"

- 1963 – Jon & Alun - "John B" (Relax Your Mind)

- 1965 – Barry McGuire

- 1966 – The Beach Boys ("Sloop John B") Can. #2[38]

- 1966 - The Merrymen featuring Emile Straker - "Wreck of the John B" (Caribbean Treasure Chest)

- 1966 – Cornelis Vreeswijk and Ann-Louise Hansson - "Jag hade en gång en båt" ("Once I Had A Boat")

- 1966 – The Ventures

- 1967 – Gary Lewis & The Playboys - “Down on the Sloop John B.”

- 1967 – Marta Kristen and Billy Mumy sing a version in Lost in Space (S3E14 Castles In Space)

- 1969 – Laurel Aitken - released as (Sloop) John B

1970s

- 1970 – Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed - "Wreck of the John B" on album Me & Jerry

- 1972 – Joseph Spence (Good Morning Mr. Walker)

- 1973 – London Welsh Male Voice Choir [39]

- 1979 – Bill Sharkey

- 1979 – The Irish Rovers (Tall Ships and Salty Dogs)

1980s

- 1981 – David Thomas & the Pedestrians

- 1984 – Rainy Day, featuring members of Rain Parade, The Dream Syndicate, and The Three O'Clock (Rainy Day)

1990s

- 1997 – Arjen Anthony Lucassen Strange Hobby

- 1998 – Jerry Jeff Walker

- 1999 – Tom Fogerty (The Very Best of Tom Fogerty)

2000s

- 2000 - Fisherman's Friends (Suck'em and Sea).[40]

- 2000 – Catch 22 - "Wreck of the Sloop John B"

- 2001 – Me First and the Gimme Gimmes

- 2003 – Ulfuls - "Sleep John B" (Japanese)

- 2004 – Dan Zanes & Festival Five Folk (Sea Music)

- 2004 – The Dicey Doh Singers (Classic Maritime Music from Smithsonian Folkways)

- 2007 – Relient K

- 2007 – Okkervil River - "John Allyn Smith Sails"

- 2009 – Simple Minds (Graffiti Soul, deluxe edition)

2010s

- 2010 – Westminster Chorus (It Only Takes a Moment)

- 2011 – Bounding Main (Kraken Up)

- 2012 – Tom McRae (From The Lowlands)

- 2012 – Al Jardine (A Postcard from California)

- 2012 – Dwight Yoakam (at The Live Room)

- 2012 – Aurelio Voltaire - "Screw the Ocampa" (BiTrektual)

- 2016 – Triángulo de Amor Bizarro - "A cantiga de Juan C"

- 2017 – AJR – “Call My Dad”

2020s

- 2022 - Isle 'Ave a Shanty - Swinging the Lamp album.[41]

Chart history

|

Weekly singles charts

|

Year-end charts

|

References

- Moskowitz 2015, p. 43.

- "Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Songs of All-Time". Rolling Stone. April 7, 2011.

- Richard Le Gallienne (December 1916). "Coral Islands and Mangrove-Trees". Harper's Monthly Magazine. 134 (799): 82–83.

- Le Gallienne, Pieces of Eight, p. 30

- Unterberger, Richie. "Great Moments in Folk Rock: Lists of Aunthor Favorites". www.richieunterberger.com. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Scullati, Gene (September 1968). "Villains and Heroes: In Defense of the Beach Boys". Jazz & Pop. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- Perlmutter, Adam (May 9, 2016). "'Sloop John B' Has Seen a Sea Change Throughout the Years". Acoustic Guitar.

- "Before TikTok Inspired a Rising Tide for Sea Shanties, the Beach Boys Charted One of Their Own". 16 January 2021.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 18 - Blowin' in the Wind: Pop discovers folk music. [Part 1]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- The Pet Sounds Sessions: "The Making Of Pet Sounds" booklet, pg. 25-26

- Matthew, Jacobs (April 16, 2013). "LSD's 70th Anniversary: 10 Rock Lyrics From The 1960s That Pay Homage To Acid". Huffington Post.

- Mojo Staff (April 24, 2015). "The Beach Boys' 50 Greatest Songs". MOJO.

- Granata, Charles L. (2003). Wouldn't it Be Nice: Brian Wilson and the Making of the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds. Chicago Review Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-55652-507-0.

- The Pet Sounds Sessions: "The Making Of Pet Sounds" booklet, pg. 26

- Hartman, Kent (2012). The Wrecking Crew: The Inside Story of Rock and Roll's Best Kept Secret. Thomas Dunne. pp. 149–151. ISBN 9780312619749. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

-

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. pp. 130–31. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Murrels, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Disks. Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 978-0214205125.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B". Single Top 100. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. March 26, 1966. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- "Single Picks of the Week" (PDF). Record World. March 26, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-17.

- "Fisherman's Friends". www.setlist.fm. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Sloop John B". www.last.fm. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Cambridge Folk Festival". www.propermusic.com. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Brian Wilson & Al Jardine - Sloop John B (Official Video)". YouTube.

- Monger, Garry (2022). "The Port of Wisbech". The Fens (51): 20.

- "Swinging the Lamp". www.isleaveashanty. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- Slowinski, Craig. "Pet Sounds LP". beachboysarchives.com. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- Alt Miller, Yvette (2011). Angels at the Table: A Practical Guide to Celebrating Shabbat. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 274. ISBN 978-1441-12397-8. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Conn, David (May 9, 2007). "FC United rise and shine on a sense of community". The Guardian. London.

- FC United of Manchester - Sloop John B Retrieved 09-21-11

- Gray, Lisa (17 October 2008). "Reid refers 'racist' Rangers song to police". independent.co.uk. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Williams, Martin (30 August 2021). "Charities condemn 'racist anti-Irish' march before Rangers v Celtic game". HeraldScotland.com. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Bradley, Joseph M. (2013). "When the Past Meets the Present: The Great Irish Famine and Scottish Football". Éire-Ireland. 48 (1–2): 230–245. doi:10.1353/eir.2013.0002. S2CID 162271495. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Original versions of (The Wreck of the) John B by the Weavers | SecondHandSongs". SecondHandSongs.

- "Lonnie Donegan". The Official Charts Company.

- "Jimmie Rodgers". Billboard.

- "CHUM Hit Parade - September 12, 1960".

- "RPM Magazine - May 16, 1966 - page 5" (PDF).

- "History of the Original Boy Band". www.londonwelshmvc.org. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- "Suck'em and Sea". www.last.fm. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "Isle 'Ave a Shanty". www.elyfolkfestival.co.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B" (in French). Ultratop 50.

- "RPM Top 100 Singles - May 16, 1966" (PDF).

- Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. p. 96. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts.

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Sloop John B". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- "The Beach Boys – Sloop John B". VG-lista.

- "SA Charts 1965–March 1989". Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "The Official Charts Company - God Only Knows by The Beach Boys Search". The Official Charts Company. 4 April 2014.

- "The Beach Boys Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- "Cash Box Top 100 Singles, May 14, 1966". Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- The 100 Best-Selling Singles of 1966

- Musicoutfitters.com

- "Cash Box Year-End Charts: Top 100 Pop Singles, December 24, 1966". Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2018.