Shangdu

Shangdu (Chinese: 上都; lit. 'Upper Capital'; Mandarin pronunciation: [ʂɑ̂ŋ tú]; Mongolian: ᠱᠠᠩᠳᠤ Шанду, Šandu), also known as Xanadu (/ˈzænəduː/ ZAN-ə-doo), was the summer capital[1][2] of the Yuan dynasty of China before Kublai moved his throne to the former Jin dynasty capital of Zhōngdū (Chinese: 中都; lit. 'Middle Capital') which was renamed Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing). Shangdu is located in the present-day Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia. In June 2012, it was made a World Heritage Site for its historical importance and for the unique blending of Mongolian and Chinese culture.[3]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Ruins of Shangdu | |

| Location | Shangdu Town, Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia, China |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 1389 |

| Inscription | 2020 (44th Session) |

| Area | 25,131.27 ha |

| Buffer zone | 150,721.96 ha |

| Coordinates | 42°21′35″N 116°10′45″E |

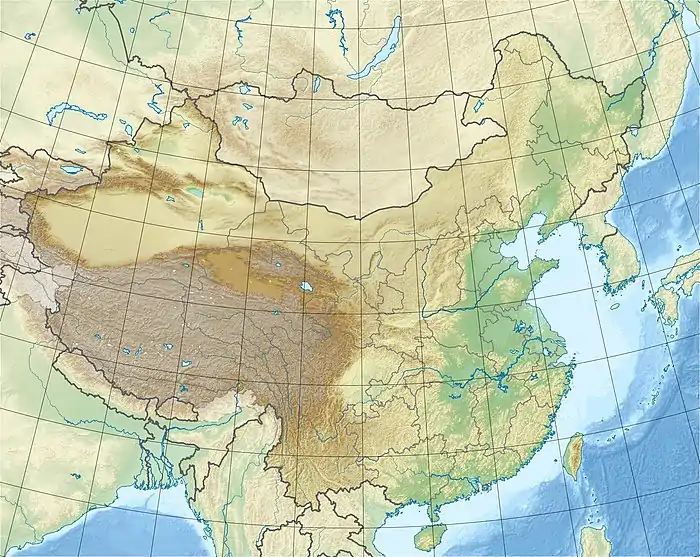

Location of Shangdu  Shangdu (China) | |

| Shangdu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 上都 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shàngdū | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Upper Capital | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Venetian traveller Marco Polo described Shangdu to Europeans after visiting it in 1275. It was conquered in 1369 by the Ming dynasty army under the Hongwu Emperor. In 1797, historical accounts of the city inspired the famous poem Kubla Khan by the English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Descriptions

Shangdu was located in what is now Shangdu Town, Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia, 350 kilometres (220 mi) north of Beijing. It is about 28 kilometres (17 mi) northwest of the modern town of Duolun. The layout of the capital is roughly square shaped with sides of about 2.2 km (1.4 mi). It consists of an "outer city", and an "inner city" in the southeast of the capital which has also roughly a square layout with sides about 1.4 km (0.87 mi), and the palace, where Kublai Khan stayed in summer. The palace has sides of roughly 550 m (1,800 ft), covering an area of around 40% the size of the Forbidden City in Beijing. The most visible modern-day remnants are the earthen walls though there is also a ground-level, circular brick platform in the centre of the inner enclosure.

The city, originally named Kaiping (开平, Kāipíng, "open and flat"), was designed by Chinese architect Liu Bingzhong from 1252 to 1256,[4] and Liu implemented a "profoundly Chinese scheme for the city's architecture".[5] In 1264 it was renamed Shangdu by Kublai Khan. At its zenith, over 100,000 people lived within its walls. In 1369 Shangdu was occupied by the Ming army, put to the torch and its name reverted to Kaiping. The last reigning Khan Toghun Temür fled the city, which was abandoned for several hundred years.[6]

In 1872, Steven Bushell, affiliated with the British Legation in Beijing, visited the site and reported that remains of temples, blocks of marble, and tiles were still to be found there. By the 1990s, all these artifacts were completely gone, most likely collected by the inhabitants of the nearby town of Dolon Nor to construct their houses. The artwork is still seen in the walls of some Dolon Nor buildings.[6]

Today, only ruins remain, surrounded by a grassy mound that was once the city walls. Since 2002, a restoration effort has been undertaken.[6]

By Marco Polo (1278)

The Venetian explorer Marco Polo is widely believed to have visited Shangdu in about 1275. In about 1298–99, he dictated the following account:

And when you have ridden three days from the city last mentioned, between north-east and north, you come to a city called Chandu, which was built by the Khan now reigning. There is at this place a very fine marble palace, the rooms of which are all gilt and painted with figures of men and beasts and birds, and with a variety of trees and flowers, all executed with such exquisite art that you regard them with delight and astonishment.

Round this Palace a wall is built, inclosing a compass of 16 miles, and inside the Park there are fountains and rivers and brooks, and beautiful meadows, with all kinds of wild animals (excluding such as are of ferocious nature), which the Emperor has procured and placed there to supply food for his gerfalcons and hawks, which he keeps there in mew.[7] Of these there are more than 200 gerfalcons alone, without reckoning the other hawks. The Khan himself goes every week to see his birds sitting in mew, and sometimes he rides through the park with a leopard behind him on his horse's croup; and then if he sees any animal that takes his fancy, he slips his leopard at it, and the game when taken is made over to feed the hawks in mew. This he does for diversion.

Moreover at a spot in the Park where there is a charming wood he has another Palace built of cane, of which I must give you a description. It is gilt all over, and most elaborately finished inside. It is stayed on gilt and lacquered columns, on each of which is a dragon all gilt, the tail of which is attached to the column whilst the head supports the architrave, and the claws likewise are stretched out right and left to support the architrave. The roof, like the rest, is formed of canes, covered with a varnish so strong and excellent that no amount of rain will rot them. These canes are a good 3 palms in girth, and from 10 to 15 paces in length. They are cut across at each knot, and then the pieces are split so as to form from each two hollow tiles, and with these the house is roofed; only every such tile of cane has to be nailed down to prevent the wind from lifting it. In short, the whole Palace is built of these canes, which I may mention serve also for a great variety of other useful purposes. The construction of the Palace is so devised that it can be taken down and put up again with great celerity; and it can all be taken to pieces and removed whithersoever the Emperor may command. When erected, it is braced against mishaps from the wind by more than 200 cords of silk.

The Khan abides at this Park of his, dwelling sometimes in the Marble Palace and sometimes in the Cane Palace for three months of the year, to wit, June, July and August; preferring this residence because it is by no means hot; in fact it is a very cool place. When the 28th day of [the Moon of] August arrives he takes his departure, and the Cane Palace is taken to pieces. But I must tell you what happens when he goes away from this Palace every year on the 28th of the August [Moon]..."[8]

By Toghon Temur (1368)

The lament of Toghon Temur Khan (the "Ukhaant Khan" or "Sage Khan"), concerning the loss of Daidu (Beijing) and Heibun Shanduu (Kaiping Xanadu) in 1368, is recorded in many Mongolian historical chronicles. The Altan Tobchi version is translated as follows:

My Daidu, straight and wonderfully made of various jewels of different kinds

My Yellow Steppe of Xanadu, the summer residence of ancient Khans.

My cool and pleasant Kaiping Xanadu

My dear Daidu that I've lost on the year of the bald red rabbit

Your pleasant mist when on early mornings I ascended to the heights!

Lagan and Ibagu made it known to me, the Sage Khan.

In full knowledge I let go of dear Daidu

Nobles born foolish cared not for their state

I was left alone weeping

I became like a calf left behind on its native pastures

My eight-sided white stupa made of various precious objects.

My City of Daidu made of the nine jewels

Where I sat holding the reputation of the Great Nation

My great square City of Daidu with four gates

Where I sat holding the reputation of the Forty Tumen Mongols

My dear City of Daidu, the iron stair has been broken.

My reputation!

My precious Daidu, from where I surveyed and observed

The Mongols of every place.

My city with no winter residence to spend the winter

My summer residence of Kaiping Xanadu

My pleasant Yellow Steppe

My deadly mistake of not heeding the words of Lagan and Ibagu!

The Cane Palace had been established in sanctity

Kublai the Wise Khan spent his summers there!

I have lost Kaiping Xanadu entirely – to China.

An impure bad name has come upon the Sage Khan.

They besieged and took precious Daidu

I have lost the whole of it – to China.

A conflicting bad name has come upon the Sage Khan.

Jewel Daidu was built with many an adornment

In Kaiping Xanadu, I spent the summers in peaceful relaxation

By a hapless error they have been lost – to China.

A circling bad name has come upon the Sage Khan.

The awe-inspiring reputation carried by the Lord Khan

The dear Daidu built by the extraordinary Wise Khan (Kublai)

The bejeweled Hearth City, the revered sanctuary of the entire nation

Dear Daidu

I have lost it all – to China.

The Sage Khan, the reincarnation of all bodhisattvas,

By the destiny willed by Khan Tengri (King Heaven) has lost dear Daidu,

Lost the Golden Palace of the Wise Khan (Kublai), who is the reincarnation of all the gods,

Who is the golden seed of Genghis Khan the son of Khan Tengri (King Heaven).

I hid the Jade Seal of the Lord Khan in my sleeve and left (the city)

Fighting through a multitude of enemies, I broke through and left.

From the fighters may Buqa-Temur Chinsan for ten thousand generations

Become a Khan in the golden line of the Lord Khan.

Caught unaware I have lost dear Daidu.

When I left home, it was then that the jewel of religion and doctrine was left behind.

In the future may wise and enlightened bodhisattvas take heed and understand.

May it go around and establish itself

On the Golden Lineage of Genghis Khan.[9]

By Samuel Purchas (1625)

In 1614, the English clergyman Samuel Purchas published Purchas his Pilgrimes – or Relations of the world and the Religions observed in all ages and places discovered, from the Creation unto this Present. This book contained a brief description of Shangdu, based on the early description of Marco Polo:

In Xandu did Cublai Can build a stately Pallace, encompassing sixteen miles of plaine ground with a wall, wherein are fertile Meddowes, pleasant Springs, delightfull streames, and all sorts of beasts of chase and game, and in the middest thereof a sumpuous house of pleasure, which may be moved from place to place.[10]

In 1625 Purchas published an expanded edition of this book, recounting the voyages of famous travellers, called Purchas his Pilgrimes. The eleventh volume of this book included a more detailed description of Shangdu, attributed to Marco Polo and dated 1320:

This Citie is three dayes journey Northeastward to the Citie Xandu, which the Chan Cublai now reigning built; erecting therein a marvellous and artificiall Palace of Marble and other stones, which abutteth on the wall on one side, and the midst of the Citie on the other. He included sixteene miles within the circuit of the wall on that side where the Palace abutteth on the Citie wall, into which none can enter but by the Palace. In this enclosure or Parke are goodly meadows, springs, rivers, red and fallow Deere, Fawnes carrying thither for the Hawkes (of whom are three mewed above two hundred Gerfalcons which he goeth once a week to see) and he often useth one Leopard or more, sitting on Horses, which he setteth upon the Stagges and Deere, and having taken the beast, giveth it to the Gerfalcons, and in beholding this spectacle he taketh wonderful delight. In the middest in a faire wood he hath a royall House on pillars gilded and varnished, on every inch of which is a Dragon all gilt, which windeth his tayle about the pillar, which his head bearing up the loft, as also with his wings displayed on both sides; the cover also is of Reeds gilt and varnished, so that the rayne can doe it no injury; the reeds being three handfuls thick and ten yards log, split from knot to knot. The house itselfe also may be sundered, and taken downe like a Tent and erected again. For it is sustained, when it is set up, with two hundred silken cordes. Great Chan useth to dwell there three moneths in the yeare, to wit, in June, July and August.[11]

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1797)

In 1797, according to his own account, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was reading about Shangdu in Purchas his Pilgrimes, fell asleep, and had an opium-inspired dream. The dream caused him to begin the poem known as 'Kubla Khan'. Unfortunately Coleridge's writing was interrupted by an unnamed "person on business from Porlock", causing him to forget much of the dream, but his images of Shangdu became one of the best-known poems in the English language.

Coleridge described how he wrote the poem in the preface to his collection of poems, Christabel, Kubla Khan, and the Pains of Sleep, published in 1816:

In the summer of the year 1797, the Author, then in ill health, had retired to a lonely farm-house between Porlock and Linton, on the Exmoor confines of Somerset and Devonshire. In consequence of a slight indisposition, an anodyne had been prescribed, from the effects of which he fell asleep in his chair at the moment that he was reading the following sentence, or words of the same substance, in 'Purchas's Pilgrimes':

Here the Khan Kubla commanded a palace to be built, and a stately garden thereunto. And thus ten miles of fertile ground were inclosed with a wall.The Author continued for about three hours in a profound sleep, at least of the external senses, during which time he has the most vivid confidence, that he could not have composed less than from two to three hundred lines; if that indeed can be called composition in which all the images rose up before him as things with a parallel production of the correspondent expressions, without any sensation or consciousness of effort. On awakening he appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole, and taking his pen, ink, and paper, instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines that are here preserved. "A person on business from Porlock" interrupted him and he was never able to recapture more than "some eight or ten scattered lines and images."[12]

Coleridge's poem opens similarly to Purchas's description before proceeding to a vivid description of the palace's varied pleasures:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery. (lines 1–11)[13]

Astronomy

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) gave a continent-sized area of Saturn's moon Titan the name Xanadu, referring to Coleridge's poem.[14] Xanadu raised considerable interest in scientists after its radar image showed its terrain to be quite similar to earth's terrain with flowing rivers (probably of methane and ethane, not of water as they are on Earth), mountains (of ice, not conventional rock) and sand dunes.[15]

See also

- List of mythological places

- Karakorum, the earlier Mongol Empire capital founded by Genghis Khan, and built in stone by Ögedei Khan in 1220

- Shangri-La

- Shambhala

References

- Tomoko, Masuya (2013). "Seasonal capitals with permanent buildings in the Mongol empire". In Durand-Guédy, David (ed.). Turko-Mongol Rulers, Cities and City Life. Leiden: Brill. p. 239.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File. p. 605.

- "Xanadu (China), Bassari Country (Senegal) and Grand Bassam (Côte d'Ivoire) added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". Archived from the original on April 15, 2016.

- "Yuan dynasty". Princeton University Art Museum.

- Shatzman Steinhardt, Nancy (1999). Chinese imperial city planning. University of Hawaii Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-8248-2196-3.

Liu Bingzhong implemented a preconceived and profoundly Chinese scheme for the city's architecture.

- Man, John (2006). Kublai Khan: From Xanadu to Superpower. London: Bantam Books. pp. 104–119. ISBN 9780553817188.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Polo, Marco. "Chapter 61: Of the City of Chandu, and the Kaan's Palace There". The Travels of Marco Polo. Vol. 1. Translated by Yule, Henry.

- "Altan Tovch" Алтан Товч [Golden Button]. hicheel.com (in Mongolian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Purchas, Samuel; Featherstone, Henry; Stansby, William; Adams, John (1614). "Chapter XIII: Of the Religion of the Tartars, and Cathayans". Purchas his Pilgrimage: or Relations of the world and the Religions observed in all ages and places discovered, from the Creation unto this Present. London: William Stansby. p. 415.

- Purchas, Samuel (1625). "Chapter III: The first booke of Marcus Paulus Venetus, or of Master Marco Polo, a Gentleman of Venice, his Voyages". Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas his Pilgrimes. Vol. 14 (1906 reprint ed.). Glasgow, J. MacLehose and sons. p. 231.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1816). Christabel, Kubla Khan, and the Pains of Sleep (2nd ed.). London: William Bulmer.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1997). Selected Poetry. Oxford University Press. p. 102.

- "Planetary Names: Albedo Feature: Xanadu on Titan". IAU.

- "Cassini Reveals Titan's Xanadu Region to Be an Earth-Like Land". NASA.