Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca[note 1] is a South American psychoactive brew, traditionally used by Indigenous cultures and folk healers in Amazon and Orinoco basins for spiritual ceremonies, divination, and healing a variety of psychosomatic complaints. Originally restricted to areas of Peru, Brazil, Colombia and Ecuador, in the middle of 20th century it became widespread in Brazil in context of appearance of syncretic religions that uses ayahuasca as a sacrament, like Santo Daime, União do Vegetal and Barquinha, which blend elements of Amazonian Shamanism, Christianity, Kardecist Spiritism, and African-Brazilian religions such as Umbanda, Candomblé and Tambor de Mina, later expanding to several countries across all continents, notably the United States and Western Europe, and, more incipiently, in Eastern Europe, South Africa, Australia, and Japan.[1][2][3]

More recently, new phenomena regarding ayahuasca use have evolved and moved to urban centers in North America and Europe, with the emergence of neoshamanic hybrid rituals and spiritual and recreational drug tourism.[4][5] Also, anecdotal evidence, studies conducted among ayahuasca consumers and clinical trials suggest that ayahuasca has broad therapeutic potential, especially for the treatment of substance dependence, anxiety, and mood disorders.[6][7][8][9][10] Thus, currently, despite continuing to be used in a traditional way, ayahuasca is also consumed recreationally worldwide, as well as used in modern medicine.

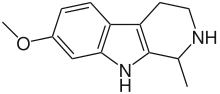

Ayahuasca is commonly made by the prolonged decoction of the stems of the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and the leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub, although hundreds of species are used in addition or substitution (See "Preparation" below).[11] P. viridis contains N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a highly psychedelic substance, although orally inactive, and B. caapi is rich on harmala alkaloids, such as harmine, harmaline and tetrahydroharmine (THH), which can act as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOi), halting liver and gastrointestinal metabolism of DMT, allowing it to reach the systemic circulation and the brain, where it activates 5-HT1A/2A/2C receptors in frontal and paralimbic areas.[12][13]

Etymology

Ayahuasca is the hispanicized (traditional) spelling of a word in the Quechuan languages, which are spoken in the Andean states of Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia—speakers of Quechuan languages who use the modern Alvarado orthography spell it ayawaska.[14] This word refers both to the liana Banisteriopsis caapi, and to the brew prepared from it. In the Quechua languages, aya means "spirit, soul", or "corpse, dead body", and waska means "rope" or "woody vine", "liana".[15] The word ayahuasca has been variously translated as "liana of the soul", "liana of the dead", and "spirit liana".[16] In the cosmovision of its users, the ayahuasca is the vine that allows the spirit to wander detached from the body, entering the spiritual world, otherwise forbidden for the alive. In Brazil it is sometimes called hoasca or oasca.

Although ayahuasca is the most widely used terminology in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Brazil, the brew is known by many names throughout Northern South America:

- yagé (or yajé, from the Cofán language or iagê in Portuguese). Relatively spread use in Andean and Amazonian regions throughout the borders of Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Brazil.[17] Cofán people also uses oofa

- caapi (or kahpi/gahpi in Tupi–Guarani language or kaapi in proto-Arawak language), used to address both the brew and the B. caapi itself. Meaning "weed" or "thin leaf", was the word utilized by Spruce for naming the liana[18]

- pinde (or pindê/pilde), used by the Colorado people[19]

- patem (or nátema), from the Chicham languages[20][21]

- shori, mii (or miiyagi) and uni, from the Yaminawa language[22][23]

- nishi cobin, from the Shipibo language[24]

- nixi pae, shuri, ondi, rambi and rame, from the Kashinawa language[25][26][27]

- kaji, kadana and kadanapira, used by Tucano people[28]

- kamarampi (or kamalampi) and hananeroca, from the Arawakan languages[29]

- bakko, from Bora-Muiname language[30]

- jono pase, useb by Ese'Ejja people[31]

- uipa, from Guahibo language[32]

- napa (or nepe/nepi), used by Tsáchila people[33]

- Biaxije, from Camsá language[34]

- Cipó ("liana") or Vegetal, in Portuguese language, used by União do Vegetal church members

- Daime or Santo Daime, meaning "give me" in Portuguese, the term was coined by Santo Daime's founder Mestre Irineu in the 1940s, from a prayer dai-me alegria, dai-me resistência ("give-me happyness, give me strength"). Daime members also uses the words Luz ("light") or Santa Luz ("holy light")

- Some nomenclature are created by the cultural and symbolic signification of ayahuasca, with names like planta professora ("plant teacher"), professor dos professores ("teacher of the teachers"), sagrada medicina ("holy medicine") or la purga ("the purge").

In the last decades, two new important terminologies emerged. Both are commonly used in the Western world in neoshamanic, recreative or pharmaceutical contexts to address ayahuasca-like substances created without the traditional botanical species, due to it being expensive and/or hard to find in these countries. These concepts are surrounded by some controversies involving patents, commodification and biopiracy:[35][36][37]

- Anahuasca (ayahuasca analogues). A term usually used to refers the ayahuasca produced with different plant species as sources of DMT (like Mimosa hostilis) or β-carbolines (like Peganum harmala).[38]

- Pharmahuasca (pharmaceutical ayahuasca). Indicate the pills produced with freebase DMT, synthetic harmaline, MAOi medications (such as moclobemide) and other isolated/purified compounds or extracts[39]

History

Evidence of Banisteriopsis caapi use in South America dates back at least 1,000 years, as demonstrated by a bundle containing the residue of the beta-carboline harmine and various other preserved psychoactive alkaloids such as bufotenin and cocaine in a cave in southwestern Bolivia, discovered in 2010.[40][41]

In the 16th century, Christian missionaries from Spain first encountered Indigenous people in the western Amazonian basin of South America using ayahuasca; their earliest reports described it as "the work of the devil".[42] In 1905, the active chemical constituent of B. caapi was named telepathine, but in 1927, it was found to be identical to a chemical already isolated from Peganum harmala and was given the name harmine.[43] Beat writer William S. Burroughs read a paper by Richard Evans Schultes on the subject and while traveling through South America in the early 1950s sought out ayahuasca in the hopes that it could relieve or cure opiate addiction (see The Yage Letters). Ayahuasca became more widely known when the McKenna brothers published their experience in the Amazon in True Hallucinations. Dennis McKenna later studied pharmacology, botany, and chemistry of ayahuasca and oo-koo-he, which became the subject of his master's thesis.

Richard Evans Schultes allowed Claudio Naranjo to make a special journey by canoe up the Amazon River to study ayahuasca with the South American Indians. He brought back samples of the beverage and published the first scientific description of the effects of its active alkaloids.[44]

In Brazil, a number of modern religious movements based on the use of ayahuasca have emerged, the most famous being Santo Daime, Barquinha and the União do Vegetal (or UDV),[45] usually in an animistic context that may be shamanistic or, more often (as with Santo Daime and the UDV), integrated with Christianity. Both Santo Daime and União do Vegetal now have members and churches throughout the world. Similarly, the US and Europe have started to see new religious groups develop in relation to increased ayahuasca use.[46] Some Westerners have teamed up with shamans in the Amazon forest regions, forming ayahuasca healing retreats that claim to be able to cure mental and physical illness and allow communication with the spirit world.

In recent years, the brew has been popularized by Wade Davis (One River), English novelist Martin Goodman in I Was Carlos Castaneda,[47] Chilean novelist Isabel Allende,[48] writer Kira Salak,[49][50] author Jeremy Narby (The Cosmic Serpent), author Jay Griffiths (Wild: An Elemental Journey), American novelist Steven Peck, radio personality Robin Quivers,[51], writer Paul Theroux (Figures in a Landscape: People and Places)[52] and NFL quarterback Aaron Rodgers.[53]

Preparation

Sections of Banisteriopsis caapi vine are macerated and boiled alone or with leaves from any of a number of other plants, including Psychotria viridis (chacruna), Diplopterys cabrerana (also known as chaliponga and chacropanga),[54] and Mimosa tenuiflora, among other ingredients which can vary greatly from one shaman to the next. The resulting brew may contain the powerful psychedelic drug DMT and MAO inhibiting harmala alkaloids, which are necessary to make the DMT orally active. The traditional making of ayahuasca follows a ritual process that requires the user to pick the lower Chacruna leaf at sunrise, then say a prayer. The vine must be "cleaned meticulously with wooden spoons"[55] and pounded "with wooden mallets until it's fibre."[55]

Brews can also be made with plants that do not contain DMT, Psychotria viridis being replaced by plants such as Justicia pectoralis, Brugmansia, or sacred tobacco, also known as mapacho (Nicotiana rustica), or sometimes left out with no replacement. This brew varies radically from one batch to the next, both in potency and psychoactive effect, based mainly on the skill of the shaman or brewer, as well as other admixtures sometimes added and the intent of the ceremony. Natural variations in plant alkaloid content and profiles also affect the final concentration of alkaloids in the brew, and the physical act of cooking may also serve to modify the alkaloid profile of harmala alkaloids.[56][57]

The actual preparation of the brew takes several hours, often taking place over the course of more than one day. After adding the plant material, each separately at this stage, to a large pot of water, it is boiled until the water is reduced by half in volume. The individual brews are then added together and brewed until reduced significantly. This combined brew is what is taken by participants in ayahuasca ceremonies.

Traditional use

The uses of ayahuasca in traditional societies in South America vary greatly.[58] Some cultures do use it for shamanic purposes, but in other cases, it is consumed socially among friends, in order to learn more about the natural environment, and even in order to visit friends and family who are far away.[58]

Nonetheless, people who work with ayahuasca in non-traditional contexts often align themselves with the philosophies and cosmologies associated with ayahuasca shamanism, as practiced among Indigenous peoples like the Urarina of the Peruvian Amazon.[59][58] Dietary taboos are often associated with the use of ayahuasca,[60] although these seem to be specific to the culture around Iquitos, Peru, a major center of ayahuasca tourism.[58]

In the rainforest, these taboos tend towards the purification of one's self—abstaining from spicy and heavily seasoned foods, excess fat, salt, caffeine, acidic foods (such as citrus) and sex before, after, or during a ceremony. A diet low in foods containing tyramine has been recommended, as the speculative interaction of tyramine and MAOIs could lead to a hypertensive crisis; however, evidence indicates that harmala alkaloids act only on MAO-A, in a reversible way similar to moclobemide (an antidepressant that does not require dietary restrictions). Dietary restrictions are not used by the highly urban Brazilian ayahuasca church União do Vegetal, suggesting the risk is much lower than perceived and probably non-existent.[60]

Ceremony and the role of shamans

Shamans, curanderos and experienced users of ayahuasca advise against consuming ayahuasca when not in the presence of one or several well-trained shamans.[61]

In some areas, there are purported brujos (Spanish for "witches") who masquerade as real shamans and who entice tourists to drink ayahuasca in their presence. Shamans believe one of the purposes for this is to steal one's energy and/or power, of which they believe every person has a limited stockpile.[61]

The shamans lead the ceremonial consumption of the ayahuasca beverage,[62] in a rite that typically takes place over the entire night. During the ceremony, the effect of the drink lasts for hours. Prior to the ceremony, participants are instructed to abstain from spicy foods, red meat and sex.[63] The ceremony is usually accompanied with purging which include vomiting and diarrhea, which is believed to release built-up emotions and negative energy.[64]

Traditional brew

_en_floraci%C3%B3n.jpg.webp)

Traditional ayahuasca brews are usually made with Banisteriopsis caapi as an MAOI, while dimethyltryptamine sources and other admixtures vary from region to region. There are several varieties of caapi, often known as different "colors", with varying effects, potencies, and uses.

DMT admixtures:

- Psychotria viridis (Chacruna)[65] – leaves

- Diplopterys cabrerana (Chaliponga, Chagropanga, Banisteriopsis rusbyana)[65] – leaves

- Psychotria carthagenensis (Amyruca)[65] – leaves

- Mimosa tenuiflora (M. hostilis) - root bark

Other common admixtures:

- Justicia pectoralis[66]

- Brugmansia sp. (Toé)[65]

- Opuntia sp.[67]

- Epiphyllum sp. [67]

- Cyperus sp.[67]

- Nicotiana rustica[65] (Mapacho, variety of tobacco)

- Ilex guayusa,[65] a relative of yerba mate

- Lygodium venustum, (Tchai del monte)[67]

- Phrygilanthus eugenioides and Clusia sp (both called Miya)[67]

- Lomariopsis japurensis (Shoka)[67]

Common admixtures with their associated ceremonial values and spirits:

- Ayahuma[65] bark: Cannon Ball tree. Provides protection and is used in healing susto (soul loss from spiritual fright or trauma).

- Capirona[65] bark: Provides cleansing, balance and protection. It is noted for its smooth bark, white flowers, and hard wood.

- Chullachaki caspi[65] bark (Brysonima christianeae): Provides cleansing to the physical body. Used to transcend physical body ailments.

- Lopuna blanca bark: Provides protection.

- Punga amarilla bark: Yellow Punga. Provides protection. Used to pull or draw out negative spirits or energies.

- Remo caspi[65] bark: Oar Tree. Used to move dense or dark energies.

- Wyra (huaira) caspi[65] bark (Cedrelinga catanaeformis): Air Tree. Used to create purging, transcend gastro/intestinal ailments, calm the mind, and bring tranquility.

- Shiwawaku bark: Brings purple medicine to the ceremony.

- Uchu sanango: Head of the sanango plants.

- Huacapurana: Giant tree of the Amazon with very hard bark.

- Bobinsana: Mermaid Spirit. Provides major heart chakra opening, healing of emotions and relationships.

Non-traditional usage

In the late 20th century, the practice of ayahuasca drinking began spreading to Europe, North America and elsewhere.[68] The first ayahuasca churches, affiliated with the Brazilian Santo Daime, were established in the Netherlands. A legal case was filed against two of the Church's leaders, Hans Bogers (one of the original founders of the Dutch Santo Daime community) and Geraldine Fijneman (the head of the Amsterdam Santo Daime community). Bogers and Fijneman were charged with distributing a controlled substance (DMT); however, the prosecution was unable to prove that the use of ayahuasca by members of the Santo Daime constituted a sufficient threat to public health and order such that it warranted denying their rights to religious freedom under ECHR Article 9. The 2001 verdict of the Amsterdam district court is an important precedent. Since then groups that are not affiliated to the Santo Daime have used ayahuasca, and a number of different "styles" have been developed, including non-religious approaches.[69]

Ayahuasca analogs

In modern Europe and North America, ayahuasca analogs are often prepared using non-traditional plants which contain the same alkaloids. For example, seeds of the Syrian rue plant can be used as a substitute for the ayahuasca vine, and the DMT-rich Mimosa hostilis is used in place of chacruna. Australia has several indigenous plants which are popular among modern ayahuasqueros there, such as various DMT-rich species of Acacia.

The name "ayahuasca" specifically refers to a botanical decoction that contains Banisteriopsis caapi. A synthetic version, known as pharmahuasca, is a combination of an appropriate MAOI and typically DMT. In this usage, the DMT is generally considered the main psychoactive active ingredient, while the MAOI merely preserves the psychoactivity of orally ingested DMT, which would otherwise be destroyed in the gut before it could be absorbed in the body. In contrast, traditionally among Amazonian tribes, the B. Caapi vine is considered to be the "spirit" of ayahuasca, the gatekeeper, and guide to the otherworldly realms.[70]

Brews similar to ayahuasca may be prepared using several plants not traditionally used in South America:

DMT admixtures:

- Acacia maidenii (Maiden's wattle) – bark *not all plants are "active strains", meaning some plants will have very little DMT and others larger amounts

- Acacia phlebophylla, and other Acacias, most commonly employed in Australia – bark

- Anadenanthera peregrina, A. colubrina, A. excelsa, A. macrocarpa

- Desmanthus illinoensis (Illinois bundleflower) – root bark is mixed with a native source of beta-Carbolines (e.g., passion flower in North America) to produce a hallucinogenic drink called prairiehuasca.[71]

MAOI admixtures:

- Harmal (Peganum harmala, Syrian rue) – seeds

- Passion flower

- synthetic MAOIs, especially RIMAs (due to the dangers presented by irreversible MAOIs)

Effects

Adverse effects

Vomiting can follow ayahuasca ingestion and may harm people with conditions such as esophagus fissure, gastric ulcer, early pregnancy and similar.[72] Vomiting is considered by many shamans and experienced users of ayahuasca to be a purging and an essential part of the experience, representing the release of negative energy and emotions built up over the course of one's life.[61]: 81–85 Others report purging in the form of diarrhea and hot/cold flashes.

The ingestion of ayahuasca can also cause significant but temporary emotional and psychological distress. People that take ayahuasca with an active history of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, psychosis, personality disorders, or bipolar disorder, among others, are at high risk of having persisting effects after the session.[73] Excessive use could possibly lead to serotonin syndrome (although serotonin syndrome has never been specifically caused by ayahuasca except in conjunction with certain anti-depressants like SSRIs). Depending on dosage, the temporary non-entheogenic effects of ayahuasca can include tremors, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, autonomic instability, hyperthermia, sweating, motor function impairment, sedation, relaxation, vertigo, dizziness, and muscle spasms which are primarily caused by the harmala alkaloids in ayahuasca. Long-term negative effects are not known.[74][75]

A few deaths linked to participation in the consumption of ayahuasca have been reported.[76][77][78][79] Some of the deaths may have been due to unscreened preexisting cardiovascular conditions, interaction with drugs, such as antidepressants, recreational drugs, caffeine (due to the CYP1A2 inhibition of the harmala alkaloids), nicotine (from drinking tobacco tea for purging/cleansing), or from improper/irresponsible use due to behavioral risks or possible drug to drug interactions.[74][80][73]

Psychological effects

People who have consumed ayahuasca report having mystical experiences and spiritual revelations regarding their purpose on earth, the true nature of the universe, and deep insight into how to be the best person they possibly can.[81] Many people also report therapeutic effects, especially around depression and personal traumas.[82]

This is viewed by many as a spiritual awakening and what is often described as a near-death experience or rebirth.[61]: 67–70 It is often reported that individuals feel they gain access to higher spiritual dimensions and make contact with various spiritual or extra-dimensional beings who can act as guides or healers.[83]

The experiences that people have while under the influence of ayahuasca are also culturally influenced.[58] Westerners typically describe experiences with psychological terms like "ego death" and understand the hallucinations as repressed memories or metaphors of mental states.[58] However, at least in Iquitos, Peru (a center of ayahuasca ceremonies), those from the area describe the experiences more in terms of the actions in the body and understand the visions as reflections of their environment, sometimes including the person who they believe caused their illness, as well as interactions with spirits.[58]

Recently, ayahuasca has been found to interact specifically with the visual cortex of the brain. In one study, de Araujo et al. measured the activity in the visual cortex when they showed participants photographs. Then, they measured the activity when the individuals closed their eyes. In the control group, the cortex was activated when looking at the photos, and less active when the participant closed his eyes; however, under the influence of ayahuasca and DMT, even with closed eyes, the cortex was just as active as when looking at the photographs. This study suggests that ayahuasca activates a complicated network of vision and memory which heightens the internal reality of the participants.[84]

It is claimed that people may experience profound positive life changes subsequent to consuming ayahuasca, by author Don Jose Campos[61]: 25–28 and others.[85]

Potential therapeutic effects

There are potential antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of ayahuasca.[86][87][88][89][90] For example, in 2018 it was reported that a single dose of ayahuasca significantly reduced symptoms of treatment-resistant depression in a small placebo-controlled trial.[91] More specifically, statistically significant reductions of up to 82% in depressive scores were observed between baseline and 1, 7 and 21 days after ayahuasca administration, as measured on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Anxious-Depression subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).[92] Other placebo-controlled research has provided evidence that ayahuasca can help improve self-perceptions in those with social anxiety disorder.[93]

Ayahuasca has also been studied for the treatment of addictions and shown to be effective, with lower Addiction Severity Index scores seen in users of ayahuasca compared to controls.[94][95][96][90] Ayahuasca users have also been seen to consume less alcohol.[97]

Chemistry and pharmacology

Harmala alkaloids are MAO-inhibiting beta-carbolines. The three most studied harmala alkaloids in the B. caapi vine are harmine, harmaline and tetrahydroharmine. Harmine and harmaline are selective and reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), while tetrahydroharmine is a weak serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI).

Individual polymorphisms of the cytochrome P450-2D6 enzyme affect the ability of individuals to metabolize harmine.[98]

Legal status

Internationally, DMT is a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The Commentary on the Convention on Psychotropic Substances notes, however, that the plants containing it are not subject to international control:[99]

The cultivation of plants from which psychotropic substances are obtained is not controlled by the Vienna Convention... Neither the crown (fruit, mescal button) of the Peyote cactus nor the roots of the plant Mimosa hostilis nor Psilocybe mushrooms themselves are included in Schedule 1, but only their respective principals, mescaline, DMT, and psilocin.

A fax from the Secretary of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) to the Netherlands Ministry of Public Health sent in 2001 goes on to state that "Consequently, preparations (e.g. decoctions) made of these plants, including ayahuasca, are not under international control and, therefore, not subject to any of the articles of the 1971 Convention."[100]

Despite the INCB's 2001 affirmation that ayahuasca is not subject to drug control by international convention, in its 2010 Annual Report the Board recommended that governments consider controlling (i.e. criminalizing) ayahuasca at the national level. This recommendation by the INCB has been criticized as an attempt by the Board to overstep its legitimate mandate and as establishing a reason for governments to violate the human rights (i.e., religious freedom) of ceremonial ayahuasca drinkers.[101]

Under American federal law, DMT is a Schedule I drug that is illegal to possess or consume; however, certain religious groups have been legally permitted to consume ayahuasca.[102] A court case allowing the União do Vegetal to import and use the tea for religious purposes in the United States, Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court on November 1, 2005; the decision, released February 21, 2006, allows the UDV to use the tea in its ceremonies pursuant to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. In a similar case an Ashland, Oregon-based Santo Daime church sued for their right to import and consume ayahuasca tea. In March 2009, U.S. District Court Judge Panner ruled in favor of the Santo Daime, acknowledging its protection from prosecution under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.[103]

In 2017 the Santo Daime Church Céu do Montréal in Canada received religious exemption to use ayahuasca as a sacrament in their rituals.[104]

Religious use in Brazil was legalized after two official inquiries into the tea in the mid-1980s, which concluded that ayahuasca is not a recreational drug and has valid spiritual uses.[105]

In France, Santo Daime won a court case allowing them to use the tea in early 2005; however, they were not allowed an exception for religious purposes, but rather for the simple reason that they did not perform chemical extractions to end up with pure DMT and harmala and the plants used were not scheduled.[106] Four months after the court victory, the common ingredients of ayahuasca as well as harmala were declared stupéfiants, or narcotic schedule I substances, making the tea and its ingredients illegal to use or possess.[107]

In June 2019, Oakland, California, decriminalized natural entheogens. The City Council passed the resolution in a unanimous vote, ending the investigation and imposition of criminal penalties for use and possession of entheogens derived from plants or fungi. The resolution states: "Practices with Entheogenic Plants have long existed and have been considered to be sacred to human cultures and human interrelationships with nature for thousands of years, and continue to be enhanced and improved to this day by religious and spiritual leaders, practicing professionals, mentors, and healers throughout the world, many of whom have been forced underground."[108] In January 2020, Santa Cruz, California, and in September 2020, Ann Arbor, Michigan, decriminalized natural entheogens.[109][110][111]

Intellectual property issues

Ayahuasca has stirred debate regarding intellectual property protection of traditional knowledge.[112] In 1986 the US Patent and Trademarks Office (PTO) allowed the granting of a patent on the ayahuasca vine B. caapi. It allowed this patent based on the assumption that ayahuasca's properties had not been previously described in writing. Several public interest groups, including the Coordinating Body of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) and the Coalition for Amazonian Peoples and Their Environment (Amazon Coalition) objected. In 1999 they brought a legal challenge to this patent which had granted a private US citizen "ownership" of the knowledge of a plant that is well-known and sacred to many Indigenous peoples of the Amazon, and used by them in religious and healing ceremonies.[113]

Later that year the PTO issued a decision rejecting the patent, on the basis that the petitioners' arguments that the plant was not "distinctive or novel" were valid; however, the decision did not acknowledge the argument that the plant's religious or cultural values prohibited a patent. In 2001, after an appeal by the patent holder, the US Patent Office reinstated the patent, albeit to only a specific plant and its asexually reproduced offspring. The law at the time did not allow a third party such as COICA to participate in that part of the reexamination process. The patent, held by US entrepreneur Loren Miller, expired in 2003.[114]

See also

Notes

Explanatory notes

- Pronounced as /ˌaɪ(j)əˈwæskə/ in the UK and /ˌaɪ(j)əˈwɑːskə/ in the US. Also occasionally known in English as ayaguasca (Spanish-derived), aioasca (Brazilian Portuguese-derived), or as yagé, pronounced /jɑːˈheɪ/ or /jæˈheɪ/. Etymologically, all forms but yagé descend from the compound Quechua word ayawaska, from aya (transl. soul) and waska (transl. vine). For more names for ayahuasca, see § Nomenclature.

Citations

- Labate, Beatriz Caiuby; Jungaberle, Henrik (2011). The internationalization of ayahuasca. Performanzen, interkulturelle Studien zu Ritual, Speil and Theater. Zürich: Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-90148-4.

- Dobkin de Rios, Marlene (December 1971). "Ayahuasca—The Healing Vine". International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 17 (4): 256–269. doi:10.1177/002076407101700402. ISSN 0020-7640. PMID 5145130.

- Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (1992). Plants of the gods: their sacred, healing and hallucinogenic powers. Rochester (Vt.): Healing arts press. ISBN 978-0-89281-406-0.

- Labate, Beatriz Caiuby; Cavnar, Clancy (2018). The expanding world Ayahuasca diaspora: appropriation, integration, and legislation. Vitality of indigenous religions. Abingdon, Oxon New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-78618-8.

- Wolff, Tom John (2020-02-07). The Touristic Use of Ayahuasca in Peru: Expectations, Experiences, Meanings and Subjective Effects. Springer Nature. p. 66. ISBN 978-3-658-29373-4.

- Santos, R.G.; Landeira-Fernandez, J.; Strassman, R.J.; Motta, V.; Cruz, A.P.M. (July 2007). "Effects of ayahuasca on psychometric measures of anxiety, panic-like and hopelessness in Santo Daime members". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 112 (3): 507–513. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.012. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 17532158.

- Osório, Flávia de L.; Sanches, Rafael F.; Macedo, Ligia R.; dos Santos, Rafael G.; Maia-de-Oliveira, João P.; Wichert-Ana, Lauro; de Araujo, Draulio B.; Riba, Jordi; Crippa, José A.; Hallak, Jaime E. (March 2015). "Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a preliminary report". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 37 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 25806551.

- Bouso, José Carlos; González, Débora; Fondevila, Sabela; Cutchet, Marta; Fernández, Xavier; Ribeiro Barbosa, Paulo César; Alcázar-Córcoles, Miguel Ángel; Araújo, Wladimyr Sena; Barbanoj, Manel J.; Fábregas, Josep Maria; Riba, Jordi (2012-08-08). "Personality, Psychopathology, Life Attitudes and Neuropsychological Performance among Ritual Users of Ayahuasca: A Longitudinal Study". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e42421. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742421B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042421. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3414465. PMID 22905130.

- Palhano-Fontes, Fernanda; Alchieri, Joao C.; Oliveira, Joao Paulo M.; Soares, Bruno Lobao; Hallak, Jaime E. C.; Galvao-Coelho, Nicole; de Araujo, Draulio B. (2014), "The Therapeutic Potentials of Ayahuasca in the Treatment of Depression", The Therapeutic Use of Ayahuasca, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 23–39, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40426-9_2, ISBN 978-3-642-40425-2, S2CID 140456338, retrieved 2023-08-10

- dos Santos, Rafael G.; Osório, Flávia L.; Crippa, José Alexandre S.; Hallak, Jaime E. C. (March 2016). "Antidepressive and anxiolytic effects of ayahuasca: a systematic literature review of animal and human studies". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 38 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1701. ISSN 1516-4446. PMC 7115465. PMID 27111702.

- Schultes, R. E.; Ceballos, L. F.; Castillo, A. (1986). "[Not Available]". America Indigena. 46 (1): 9–47. ISSN 0185-1179. PMID 11631122.

- Riba, Jordi; Valle, Marta; Urbano, Gloria; Yritia, Mercedes; Morte, Adelaida; Barbanoj, Manel J. (2003-03-26). "Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion, and Pharmacokinetics". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 306 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.049882. ISSN 0022-3565. PMID 12660312. S2CID 6147566.

- Riba, Jordi; Romero, Sergio; Grasa, Eva; Mena, Esther; Carrió, Ignasi; Barbanoj, Manel J. (2006-03-31). "Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-amazonian inebriant". Psychopharmacology. 186 (1): 93–98. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0358-7. hdl:2117/9378. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 16575552. S2CID 15046798.

- Sanz-Biset, Jaume; Cañigueral, Salvador (2013-01-09). "Plants as medicinal stressors, the case of depurative practices in Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazonia)". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 145 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.09.053. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 23123268.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Bois-Mariage, Frédérick (2002). "Ayahuasca : une synthèse interdisciplinaire". Psychotropes. 8: 79–113. doi:10.3917/psyt.081.0079.

- SCHULTES, Richard Evans (1960). "Prestonia: An Amazon Narcotic or Not?". Botanical Museum Leaflets. 19 (5): 109–122. doi:10.5962/p.168526. JSTOR 41762210. S2CID 91123988.

- Spruce, Richard; Wallace, Alfred Russel (1908). Notes of a botanist on the Amazon & Andes : being records of travel on the Amazon and its tributaries, the Trombetas, Rio Negro, Uaupés, Casiquiari, Pacimoni, Huallaga, and Pastasa; as also to the cataracts of the Orinoco, along the eastern side of the Andes of Peru and Ecuador, and the shores of the Pacific, during the years 1849-1864. London: Macmillan. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.17908.

- NARANJO, Plutarco (1986). "El Ayahuasca en la arqueologia ecuatoriana". America Indigena. 46: 117–128.

- Descola, Philippe (1996). In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100, 163. ISBN 978-0-521-57467-9.

- Incayawar, Mario; Lise Bouchard; Ronald Wintrob; Goffredo Bartocci (2009). Psychiatrists and Traditional Healers: Unwitting Partners in Global Mental Health. Wiley. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-470-51683-6.

- Grob, CS; McKenna, DJ; Callaway, JC; Brito, GS; Oberlaender, G; Saide, OL; Labigalini, E; Tacla, C; Miranda, CT; Strassman, RJ; Boone, KB (1996). "Human Psychopharmacology of Hoasca: a plant hallucinogen used in ritual context in Brazil". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 184 (2): 86–94. doi:10.1097/00005053-199602000-00004. PMID 8596116. S2CID 17975501. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- Davis, E. Wade; Yost, James A. (1983). "Novel Hallucinogens from Eastern Ecuador". Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University. 29 (3): 291–295. ISSN 0006-8098.

- "Novedades - Página Jimdo de shamanesshipibos". shamanesshipibos.jimdo.com. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Kensinger, Kenneth (1976). Harner, Michael (ed.). "El uso del Banipteropsis entre los cashinahua del Perú". Alucinógenos y chamanes. Madrid: Guadarrama.

- "Kaxinawá, Rituals". Povos Indígenas do Brasil. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Rivier, Laurent; Lindgren, Jan-Erik (1972-04-01). ""Ayahuasca," the South American hallucinogenic drink: An ethnobotanical and chemical investigation". Economic Botany. 26 (2): 101–129. doi:10.1007/BF02860772. ISSN 1874-9364.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo (1987). Shamanism and art of the Eastern Tukanoan Indians. Iconography of religions. Instituut voor godsdiensthistorische beelddocumentatie. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08110-9.

- DE MORI, Brabec (2011): Tracing Hallucinations – Contributing to a Critical Ethnohistory of Ayahuasca Usage in the Peruvian Amazon

- Seifart, Frank, & Echeverri, Juan Alvaro (2015). Proto Bora-Muinane. LIAMES: Línguas Indígenas Americanas, 15(2), 279 - 311. doi:10.20396/liames.v15i2.8642303

- Desmarchelier, C.; Mongelli, E.; Coussio, J.; Ciccia, G. (1996-02-01). "Studies on the cytotoxicity, antimicrobial and DNA-binding activities of plants used by the Ese'ejas". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 50 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01334-2. ISSN 0378-8741.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo (1990). The sacred mountain of Colombia's Kogi Indians. Iconography of religions. Instituut voor godsdiensthistorische beelddocumentatie. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09274-7.

- Oller, Montserrat Ventura i (2012). "Chamanismo, liderazgo y poder indígena: el caso tsachila". Revista Española de Antropología Americana (in Spanish). 42 (1): 91–106. doi:10.5209/rev_REAA.2012.v42.n1.38637. ISSN 1988-2718.

- Huber, Randall Q. and Robert B. Reed. 1992. Vocabulario comparativo: Palabras selectas de lenguas indígenas de Colombia (Comparative vocabulary: Selected words in indigenous languages of Colombia). Bogota, Colombia: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Press, Sara V. (2022-07-25). "Ayahuasca on Trial: Biocolonialism, Biopiracy, and the Commodification of the Sacred". History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals. 63 (2): 328–353. doi:10.3368/hopp.63.2.328. ISSN 2694-3034. S2CID 251078878.

- Tupper, Kenneth W. (January 2009). "Ayahuasca healing beyond the Amazon: the globalization of a traditional indigenous entheogenic practice". Global Networks. 9 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00245.x.

- Schenberg, Eduardo Ekman; Gerber, Konstantin (October 2022). "Overcoming epistemic injustices in the biomedical study of ayahuasca: Towards ethical and sustainable regulation". Transcultural Psychiatry. 59 (5): 610–624. doi:10.1177/13634615211062962. ISSN 1363-4615. PMID 34986699. S2CID 245771857.

- Kaasik, Helle; Souza, Rita C. Z.; Zandonadi, Flávia S.; Tófoli, Luís Fernando; Sussulini, Alessandra (2020-09-08). "Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 53 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 32896230. S2CID 221543172.

- Ott, Jonathan (April 1999). "Pharmahuasca: Human Pharmacology of Oral DMT Plus Harmine". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 31 (2): 171–177. doi:10.1080/02791072.1999.10471741. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 10438001.

- Erin Blakemore (6 May 2019). "Ancient hallucinogens found in 1,000-year-old shamanic pouch". nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

A SMALL POUCH, made from three fox snouts neatly sewn together, may contain the world's earliest archaeological evidence for the consumption of ayahuasca, a psychoactive plant preparation indigenous to peoples of the Amazon basin that produces potent hallucinations.

- Miller, Melanie J.; Albarracin-Jordan, Juan; Moore, Christine; Capriles, José M. (4 June 2019). "Chemical evidence for the use of multiple psychotropic plants in a 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from South America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (23): 11207–11212. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11611207M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902174116. PMC 6561276. PMID 31061128.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff 1975, p. 48 as cited in Soibelman 1995, p. 14.

- Elger, F. (1928). "Über das Vorkommen von Harmin in einer südamerikanischen Liane (Yagé)". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 11 (1): 162–166. doi:10.1002/hlca.19280110113.

- Naranjo, Claudio (1974). The Healing Journey. Pantheon Books. pp. X. ISBN 978-0-394-48826-4.

- Santana de Rose, Isabel (2018), "Barquinha", in Gooren, Henri (ed.), Encyclopedia of Latin American Religions, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08956-0_540-1, ISBN 978-3-319-08956-0, retrieved 2023-05-19

- Labate, B.C.; Rose, I.S. & Santos, R.G. (2009). Ayahuasca Religions: a comprehensive bibliography and critical essays. Santa Cruz: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies – MAPS. ISBN 978-0-9798622-1-2.

- "Letters: Mar 19 | Books". The Guardian. 2005-03-19. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- Elsworth, Catherine (2008-03-21). "Isabel Allende: kith and tell". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- Salak, Kira. "Hell And Back". Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Salak, Kira. "Ayahuasca Healing in Peru". Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- stern show blog, podcast and videos, wcqj.com, retrieved 2012-01-14

- Theroux, Paul (2018). Figures in a Landscape: People & Places. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt / Eamon Dolan. ISBN 978-0-544-87030-7.

- "Aaron Rodgers Talks Participating in 3-Night Ayahuasca Event and His Love of Washing Dishes: It's 'Meditative'". Peoplemag. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- "Ayahuasca Vine Facts | Spirit Vine Ayahuasca Retreats". Spirit Vine. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- Levy, Ariel (12 September 2016). "The Drug of Choice for the Age of Kale". The New Yorker.

- Callaway, J. C. (June 2005). "Various Alkaloid Profiles in Decoctions of Banisteriopsis Caapi" (PDF). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 151–5. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399796. ISSN 0279-1072. OCLC 7565359. PMID 16149328. S2CID 1420203. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Callaway, J. C.; Brito, Glacus S.; Neves, Edison S. (June 2005). "Phytochemical Analyses of Banisteriopsis Caapi and Psychotria Viridis". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 145–50. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399795. ISSN 0279-1072. OCLC 7565359. PMID 16149327. S2CID 30736017.

- Hay, Mark (4 November 2020). "The Colonization of the Ayahuasca Experience". JSTOR Daily. JSTOR. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Dean, Bartholomew (2009). Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5.

- Ott, J. (1994). Ayahuasca Analogues: Pangaean Entheogens. Kennewick, WA: Natural Books. ISBN 978-0-9614234-4-5.

- Campos, Don Jose (2011). The Shaman & Ayahuasca: Journeys to Sacred Realms.

- Bob Morris (13 June 2014). "Ayahuasca: A Strong Cup of Tea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01.

- "Ayahuasca Ceremony Preparation". ayahuascahealings.com. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "The New Power Trip: Inside the World of Ayahuasca". Marie Claire. 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Rätsch, Christian (2005), pp. 704-708. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-89281-978-2

- Thoricatha, Wesley (2017-04-04). "Breaking Down the Brew: Examining the Plants Commonly Used in Ayahuasca". Psychedelic Times. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Rivier, Laurent; Lindgren, Jan-Erik (April 1972). ""Ayahuasca," the South American hallucinogenic drink: An ethnobotanical and chemical investigation". Economic Botany. 26 (2): 101–129. doi:10.1007/BF02860772. ISSN 0013-0001.

- Tupper, Kenneth (August 2008). "The Globalization of Ayahuasca: Harm Reduction or Benefit Maximization?". International Journal of Drug Policy. 19 (4): 297–303. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.517.9508. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.001. PMID 18638702.

- Alì, Maurizio (2015). "How to Disappear Completely. Community Dynamics and Deindividuation in Neo-Shamanic Urban Practices". Shaman - Journal of the International Society for Academic Research on Shamanism. 23 (1–2): 17–52 – via HAL.

- Ayahuasca DMT La Molecula Dios, Ayahuasca-Recipe.com, 2017-07-29, archived from the original on July 31, 2017, retrieved 2017-07-31

- Hegnauer, R.; Hegnauer, M. (1996). Caesalpinioideae und Mimosoideae Volume 1 Part 2. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 199. ISBN 978-3-7643-5165-6.

- "Are there people that should avoid taking ayahuasca?". Takiwasi Center - Center for rehabilitation and treatment of addiction, retreats or diets in the Amazon rainforest, research on traditional Amazonian medicines. Retrieved June 30, 2023.

- "Deciding to Take Ayahuasca | General Advice". ICEERS. 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- Gable, Robert S. (2007), "Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids" (PDF), Addiction, 102 (1): 24–34, doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01652.x, PMID 17207120, archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2017, retrieved December 29, 2016

- Schultz, Mitch (2010). DMT: The Spirit Molecule.

- Sklerov J, Levine B, Moore KA, King T, Fowler D (2005). "A fatal intoxication following the ingestion of 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in an ayahuasca preparation". J Anal Toxicol. 29 (8): 838–41. doi:10.1093/jat/29.8.838. PMID 16356341.

- Tracy McVeigh (26 April 2014). "British backpacker dies after taking hallucinogenic brew in Colombia". The Observer.

- "Politie stopt healingsessie na dood Hongaar". De Limburger. 25 April 2019.

- "American Found Dead After Taking Ayahuasca". Peruvian Times. September 14, 2012.

- "Why do people take ayahuasca?". BBC. 29 April 2014.

- Gorman, Peter (2010). Ayahuasca in My Blood: 25 Years of Medicine Dreaming. Johan Fremin. ISBN 978-1-4528-8290-1.

- Harris, Rachel (2017). Listening to Ayahuasca. Novato, California: New World Library. pp. 120–200. ISBN 978-1-60868-402-1.

- Metzner, Ralph (1999). Ayahuasca: Human Consciousness and the Spirits of Nature. pp. 46–55.

- de Araujo, DB; Ribeiro, S; Cecchi, GA; Carvalho, FM; Sanchez, TA; Pinto, JP; de Martinis, BS; Crippa, JA; Hallack, JE; Santos, AC (November 2012). "Seeing with the eyes shut: neural basis of enhanced imagery following Ayahuasca ingestion". Human Brain Mapping. 33 (11): 2550–60. doi:10.1002/hbm.21381. PMC 6870240. PMID 21922603. S2CID 18366684.

- Billen, Andrew (19 April 2019). "Extinction Rebellion Founder Gail Bradbrook: 'We're Making People's Lives Miserable but They Are Talking about the Issues'." The Times. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Sanches, Rafael Faria; de Lima Osório, Flávia; dos Santos, Rafael G.; Macedo, Ligia R.H.; Maia-de-Oliveira, João Paulo; Wichert-Ana, Lauro; de Araujo, Draulio Barros; Riba, Jordi; Crippa, José Alexandre S.; Hallak, Jaime E.C. (2016). "Antidepressant Effects of a Single Dose of Ayahuasca in Patients With Recurrent Depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 36 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1097/jcp.0000000000000436. ISSN 0271-0749. PMID 26650973. S2CID 41083002.

- Galvão, Ana C. de Menezes; de Almeida, Raíssa N.; Silva, Erick A. dos Santos; Freire, Fúlvio A. M.; Palhano-Fontes, Fernanda; Onias, Heloisa; Arcoverde, Emerson; Maia-de-Oliveira, João P.; de Araújo, Dráulio B.; Lobão-Soares, Bruno; Galvão-Coelho, Nicole L. (2018-05-08). "Cortisol Modulation by Ayahuasca in Patients With Treatment Resistant Depression and Healthy Controls". Frontiers in Psychiatry. Frontiers Media SA. 9: 185. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00185. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5952178. PMID 29867608.

- Nunes, Amanda A.; dos Santos, Rafael G.; Osório, Flávia L.; Sanches, Rafael F.; Crippa, José Alexandre S.; Hallak, Jaime E. C. (2016-05-26). "Effects of Ayahuasca and its Alkaloids on Drug Dependence: A Systematic Literature Review of Quantitative Studies in Animals and Humans". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. Informa UK Limited. 48 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1080/02791072.2016.1188225. hdl:11449/159021. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 27230395. S2CID 5840140.

- Carbonaro, Theresa M.; Gatch, Michael B. (2016). "Neuropharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine". Brain Research Bulletin. Elsevier BV. 126 (Pt 1): 74–88. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.016. ISSN 0361-9230. PMC 5048497. PMID 27126737.

- Frecska, Ede; Bokor, Petra; Winkelman, Michael (2016-03-02). "The Therapeutic Potentials of Ayahuasca: Possible Effects against Various Diseases of Civilization". Frontiers in Pharmacology. Frontiers Media SA. 7: 35. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00035. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC 4773875. PMID 26973523.

- Palhano-Fontes, Fernanda; Barreto, Dayanna; Onias, Heloisa; Andrade, Katia C.; Novaes, Morgana M.; Pessoa, Jessica A.; Mota-Rolim, Sergio A.; Osório, Flávia L.; Sanches, Rafael (15 June 2018). "Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial". Psychological Medicine. 49 (4): 655–663. doi:10.1017/S0033291718001356. PMC 6378413. PMID 29903051.

- Osório, Flávia de L.; Sanches, Rafael F.; Macedo, Ligia R.; dos Santos, Rafael G.; Maia-de-Oliveira, João P.; Wichert-Ana, Lauro; de Araujo, Draulio B.; Riba, Jordi; Crippa, José A. (March 2015). "Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a preliminary report". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 37 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 25806551.

- "A single dose of ayahuasca improves self-perception of speech performance in socially anxious people, study finds". PsyPost. 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- Fábregas, Josep Maria; González, Débora; Fondevila, Sabela; Cutchet, Marta; Fernández, Xavier; Barbosa, Paulo César Ribeiro; Alcázar-Córcoles, Miguel Ángel; Barbanoj, Manel J.; Riba, Jordi; Bouso, José Carlos (2010). "Assessment of addiction severity among ritual users of ayahuasca". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 111 (3): 257–261. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.024. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 20554400.

- Liester, Mitchell B.; Prickett, James I. (2012). "Hypotheses Regarding the Mechanisms of Ayahuasca in the Treatment of Addictions". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (3): 200–208. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.704590. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 23061319. S2CID 32698157.

- McKenna, Dennis J (2004). "Clinical investigations of the therapeutic potential of ayahuasca: rationale and regulatory challenges". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 102 (2): 111–129. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.03.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 15163593.

- Harris, Rachel; Gurel, Lee (2012). "A Study of Ayahuasca Use in North America". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (3): 209–215. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.703100. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 23061320. S2CID 24580577.

- Callaway, J. C. (June 2005). "Fast and Slow Metabolizers of Hoasca". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 157–61. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399797. ISSN 0279-1072. OCLC 7565359. PMID 16149329. S2CID 41427434.

- DMT – UN report, MAPS, 2001-03-31, archived from the original on January 21, 2012, retrieved 2012-01-14

- Ayahuasca Vault : Law : UNDCP's Ayahuasca Fax, Erowid.org, 2001-01-17, retrieved 2012-01-14

- Tupper, Kenneth W.; Labate, Beatriz C. (2012). "Plants, Psychoactive Substances and the International Narcotics Control Board: The Control of Nature and the Nature of Control" (PDF). Human Rights & Drugs. 2 (1): 17–28. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- orangebook.pdf www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov

- Ruling by District Court Judge Panner in Santo Daime case in Oregon (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-03, retrieved 2012-01-14

- Rochester, Rev Dr Jessica (2017-07-17). "How Our Santo Daime Church Received Religious Exemption to Use Ayahuasca in Canada". Chacruna. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- More on the legal status of ayahuasca can be found in the Erowid vault on the legality of ayahuasca.

- Cour d'appel de Paris, 10ème chambre, section B, dossier n° 04/01888. Arrêt du 13 janvier 2005 Court of Appeal of Paris, 10th Chamber, Section B, File No. 04/01888. Judgement of 13 January 2005

- JO, 2005-05-03. Arrêté du 20 avril 2005 modifiant l'arrêté du 22 février 1990 fixant la liste des substances classées comme stupéfiants (PDF) [Decree of 20 April 2005 amending the decree of 22 February 1990 establishing the list of substances scheduled as narcotics].

- Shalby, Colleen (5 June 2019). "Oakland becomes 2nd U.S. city to decriminalize magic mushrooms". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- McCarthy, Kelly (2020-01-29). "Santa Cruz decriminalizes psychedelic mushrooms". ABC News. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- Kaur, Harmeet (2020-01-30). "Santa Cruz decriminalizes magic mushrooms and other natural psychedelics, making it the third US city to take such a step". CNN. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- Stanton, Ryan (2020-09-22). "Ann Arbor OKs move to decriminalize psychedelic mushrooms, plants". mlive. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Tupper, Kenneth (January 2009). "Ayahuasca Healing Beyond the Amazon: The Globalization of a Traditional Indigenous Entheogenic Practice". Global Networks. 9 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00245.x. S2CID 144295220.

- "CIEL Biodiversity Program Accomplishments". Ciel.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- "The Ayahuasca Patent Case". Our Programs: Biodiversity. The Centre for International Environmental Law. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

Further reading

- Burroughs, William S. and Allen Ginsberg. The Yage Letters. San Francisco: City Lights, 1963. ISBN 978-0-87286-004-9

- Langdon, E. Jean Matteson & Gerhard Baer, eds. Portals of Power: Shamanism in South America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8263-1345-4

- Shannon, Benny. The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-925293-0

- Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-226-79012-1

- Tupper, Kenneth (August 2008). "The Globalization of Ayahuasca: Harm Reduction or Benefit Maximization?" (PDF). International Journal of Drug Policy. 19 (4): 297–303. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.517.9508. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.001. PMID 18638702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- Tupper, Kenneth (2009). "Ayahuasca Healing Beyond the Amazon: The Globalization of a Traditional Indigenous Entheogenic Practice". Global Networks. 9 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00245.x. S2CID 144295220.

- Tupper, Kenneth W.; Labate, Beatriz C. (2012). "Plants, Psychoactive Substances and the International Narcotics Control Board: The Control of Nature and the Nature of Control" (PDF). Human Rights & Drugs. 2 (1): 17–28.

- Tupper, Kenneth W.; Labate, Beatriz C. (2014). "Ayahuasca, Psychedelic Studies and Health Sciences: The Politics of Knowledge and Inquiry into an Amazonian Plant Brew" (PDF). Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (2): 71–80. doi:10.2174/1874473708666150107155042. PMID 25563448. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-22. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

External links

Media related to Ayahuasca at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ayahuasca at Wikimedia Commons