Yakan people

The Yakan people are among the major indigenous Filipino ethnolinguistic groups in the Sulu Archipelago. Having a significant number of followers of Islam, it is considered one of the 13 Moro groups in the Philippines. The Yakans mainly reside in Basilan but are also in Zamboanga City. They speak a language known as Bissa Yakan, which has characteristics of both Sama-Bajau Sinama and Tausug (Jundam 1983: 7-8). It is written in the Malayan Arabic script, with adaptations to sounds not present in Arabic (Sherfan 1976).

Students from the Datu Bantilan Dance Troupe in traditional Yakan costume with US Ambassador Kristie Kenney. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 282,715 (2020 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Basilan, Zamboanga Peninsula | |

| Languages | |

| Yakan, Tausug, Zamboangueño Chavacano, Cebuano, Filipino, English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sama-Bajau, other Moros, Lumad, Visayans, other Filipinos, other Austronesian peoples |

The Yakan have a traditional horse culture. They are renowned for their weaving traditions.[2] Culturally, they are Sama people who eventually led a life on land, mostly in Basilan and Zamboanga city. They are included as part of the Sama ethnic group, which includes the Bajau, Dilaut, Kalibugan, and other Sama groups.[3]

History

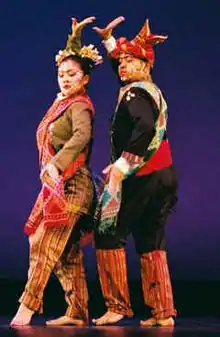

The Yakans reside in the Sulu Archipelago, situated to the west of Zamboanga in Mindanao. Traditionally they wear colorful, handwoven clothes. The women wear tight fitting short blouses and both sexes wear narrowcut pants resembling breeches. The women covers it partly with a wrap-around material while the man wraps a sash-like cloth around the waist where he places his weapon – usually a long knife. Nowadays most Yakans wear western clothes and use their traditional clothes only for cultural festivals.

The Spaniards called the Yakan, "Sameacas" and considered them an aloof and sometimes hostile hill people (Wulff 1978:149; Haylaya 1980:13).

In the early 1970s, some of the Yakan settled in Zamboanga City due to political unrest that led to armed conflict between militant Moro groups and government soldiers. The Yakan Village in Upper Calarian is famous among local and foreign tourists because of their art of weaving. Traditionally, they have used plants such as pineapple and abaca converted into fibers as basic material for weaving. Using herbal extracts from leaves, roots and barks, the Yakans dyed the fibers and produced colorful combinations and intricate designs.

The Seputangan is the most intricate design worn by the women around their waist or as a head cloth. The Palipattang is patterned after the color of the rainbow while the bunga-sama, after the python. Almost every Yakan fabric can be described as unique since the finished materials are not exactly identical. Differences may be seen in the pattern or in the design or in the distribution of colors.

Contacts with settlers from Luzon, Visayas, and the American Peace Corps brought about changes in the art and style of weaving. Many resorted to using chemical dyes, which are more convenient, and started weaving table runners, placemats, wall decor, purses, and other items that are not present in a traditional Yakan house. In other words, Yakan communities, for economic reason, catered to the needs of their customers, demonstrating their trading acumen. New designs were introduced, such as kenna-kenna, patterned after a fish; dawen-dawen, after the leaf of a vine; pene mata-mata, after the shape of an eye or the kabang buddi, a diamond-shaped design.

Examples of Yakan art

Yards of Yakan cloth on display

Yards of Yakan cloth on display A saddle panel made of wood with shell inlay

A saddle panel made of wood with shell inlay Another saddle panel made of wood with shell inlay

Another saddle panel made of wood with shell inlay A weapon sword native to the Yakans called pira

A weapon sword native to the Yakans called pira

References

- "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- de Jong, Ronald. "The last Tribes of Mindanao, the Yakan; Mountain Dwellers". ThingsAsian. Global Directions, Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Charles O. Frake (2006). Chapter 14. The Cultural Construction of Rank, Identity and Ethnic Origins in the Sulu Archipelago: compiled by James J. Fox and Clifford Sather (2006) in Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. ANU Press.