Yang–Baxter equation

In physics, the Yang–Baxter equation (or star–triangle relation) is a consistency equation which was first introduced in the field of statistical mechanics. It depends on the idea that in some scattering situations, particles may preserve their momentum while changing their quantum internal states. It states that a matrix , acting on two out of three objects, satisfies

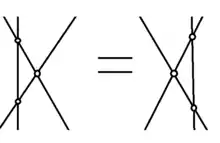

In one-dimensional quantum systems, is the scattering matrix and if it satisfies the Yang–Baxter equation then the system is integrable. The Yang–Baxter equation also shows up when discussing knot theory and the braid groups where corresponds to swapping two strands. Since one can swap three strands two different ways, the Yang–Baxter equation enforces that both paths are the same.

It takes its name from independent work of C. N. Yang from 1968, and R. J. Baxter from 1971.

General form of the parameter-dependent Yang–Baxter equation

Let be a unital associative algebra. In its most general form, the parameter-dependent Yang–Baxter equation is an equation for , a parameter-dependent element of the tensor product (here, and are the parameters, which usually range over the real numbers ℝ in the case of an additive parameter, or over positive real numbers ℝ+ in the case of a multiplicative parameter).

Let for , with algebra homomorphisms determined by

The general form of the Yang–Baxter equation is

for all values of , and .

Parameter-independent form

Let be a unital associative algebra. The parameter-independent Yang–Baxter equation is an equation for , an invertible element of the tensor product . The Yang–Baxter equation is

where , , and .

With respect to a basis

Often the unital associative algebra is the algebra of endomorphisms of a vector space over a field , that is, . With respect to a basis of , the components of the matrices are written , which is the component associated to the map . Omitting parameter dependence, the component of the Yang–Baxter equation associated to the map reads

Alternate form and representations of the braid group

Let be a module of , and . Let be the linear map satisfying for all . The Yang–Baxter equation then has the following alternate form in terms of on .

- .

Alternatively, we can express it in the same notation as above, defining , in which case the alternate form is

In the parameter-independent special case where does not depend on parameters, the equation reduces to

- ,

and (if is invertible) a representation of the braid group, , can be constructed on by for . This representation can be used to determine quasi-invariants of braids, knots and links.

Symmetry

Solutions to the Yang–Baxter equation are often constrained by requiring the matrix to be invariant under the action of a Lie group . For example, in the case and , the only -invariant maps in are the identity and the permutation map . The general form of the -matrix is then for scalar functions .

The Yang–Baxter equation is homogeneous in parameter dependence in the sense that if one defines , where is a scalar function, then also satisfies the Yang–Baxter equation.

The argument space itself may have symmetry. For example translation invariance enforces that the dependence on the arguments must be dependence only on the translation-invariant difference , while scale invariance enforces that is a function of the scale-invariant ratio .

Parametrizations and example solutions

A common ansatz for computing solutions is the difference property, , where R depends only on a single (additive) parameter. Equivalently, taking logarithms, we may choose the parametrization , in which case R is said to depend on a multiplicative parameter. In those cases, we may reduce the YBE to two free parameters in a form that facilitates computations:

for all values of and . For a multiplicative parameter, the Yang–Baxter equation is

for all values of and .

The braided forms read as:

In some cases, the determinant of can vanish at specific values of the spectral parameter . Some matrices turn into a one dimensional projector at . In this case a quantum determinant can be defined .

Example solutions of the parameter-dependent YBE

- A particularly simple class of parameter-dependent solutions can be obtained from solutions of the parameter-independent YBE satisfying , where the corresponding braid group representation is a permutation group representation. In this case, (equivalently, ) is a solution of the (additive) parameter-dependent YBE. In the case where and , this gives the scattering matrix of the Heisenberg XXX spin chain.

- The -matrices of the evaluation modules of the quantum group are given explicitly by the matrix

Then the parametrized Yang-Baxter equation with the multiplicative parameter is satisfied:

Classification of solutions

There are broadly speaking three classes of solutions: rational, trigonometric and elliptic. These are related to quantum groups known as the Yangian, affine quantum groups and elliptic algebras respectively.

Set-theoretic Yang–Baxter equation

Set-theoretic solutions were studied by Drinfeld.[1] In this case, there is an -matrix invariant basis for the vector space in the sense that the -matrix maps the induced basis on to itself. This then induces a map given by restriction of the -matrix to the basis. The set-theoretic Yang–Baxter equation is then defined using the 'twisted' alternate form above, asserting

as maps on . The equation can then be considered purely as an equation in the category of sets.

Examples

- .

- where , the transposition map.

- If is a (right) shelf, then is a set-theoretic solution to the YBE.

Classical Yang–Baxter equation

Solutions to the classical YBE were studied and to some extent classified by Belavin and Drinfeld.[2] Given a 'classical -matrix' , which may also depend on a pair of arguments , the classical YBE is (suppressing parameters)

This is quadratic in the -matrix, unlike the usual quantum YBE which is cubic in .

This equation emerges from so called quasi-classical solutions to the quantum YBE, in which the -matrix admits an asymptotic expansion in terms of an expansion parameter

The classical YBE then comes from reading off the coefficient of the quantum YBE (and the equation trivially holds at orders ).

References

- Jimbo, Michio (1989). "Introduction to the Yang-Baxter equation". International Journal of Modern Physics A. 4 (15): 3759–3777. Bibcode:1989IJMPA...4.3759J. doi:10.1142/S0217751X89001503. MR 1017340.

- H.-D. Doebner, J.-D. Hennig, eds, Quantum groups, Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Mathematical Physics, Arnold Sommerfeld Institute, Clausthal, FRG, 1989, Springer-Verlag Berlin, ISBN 3-540-53503-9.

- Vyjayanthi Chari and Andrew Pressley, A Guide to Quantum Groups, (1994), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ISBN 0-521-55884-0.

- Jacques H.H. Perk and Helen Au-Yang, "Yang–Baxter Equations", (2006), arXiv:math-ph/0606053.

- Drinfeld, Vladimir (1992). Quantum groups : proceedings of workshops held in the Euler International Mathematical Institute, Leningrad, Fall 1990. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/BFb0101175. ISBN 978-3-540-55305-2. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Belavin, A. A.; Drinfel'd, V. G. (1983). "Solutions of the classical Yang - Baxter equation for simple Lie algebras". Functional Analysis and Its Applications. 16 (3): 159–180. doi:10.1007/BF01081585. S2CID 123126711. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

External links

- "Yang-Baxter equation", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]