Yantra

Yantra (यन्त्र) (literally "machine, contraption"[1]) is a geometrical diagram, mainly from the Tantric traditions of the Indian religions. Yantras are used for the worship of deities in temples or at home; as an aid in meditation; used for the benefits given by their supposed occult powers based on Hindu astrology and tantric texts. They are also used for adornment of temple floors, due mainly to their aesthetic and symmetric qualities. Specific yantras are traditionally associated with specific deities and/or certain types of energies used for accomplishment of certain tasks, vows, that may be materialistic or spiritual in nature. It becomes a prime tool in certain sadhanas performed by the sadhaka the spiritual seeker. Yantras hold great importance in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Representations of the yantra in India have been considered to date back to 11,000–10,000 years BCE.[2] The Baghor stone, found in an upper-paleolithic context in the Son River valley, is considered the earliest example[3] by G.R. Sharma, who was involved in the excavation of the stone (it was dated to 25,000 - 20,000 BCE). The triangular stone, which includes triangular engravings on one side, was found daubed in ochre, in what was considered a site related to worship. Worship of goddesses in that region was found to be practiced in a similar manner to the present day.[4] Kenoyer, who was also involved in the excavation, considered it to be associated with Shakti. This triangular shape looks very much similar to Kali Yantra and Muladhara Chakra.[5]

Mantras, the Sanskrit syllables inscribed on yantras, are essentially "thought forms" representing divinities or cosmic powers, which exert their influence by means of sound-vibrations.[6]

Etymology

In Rigvedic Sanskrit, it meant an instrument for restraining or fastening, a prop, support or barrier, etymologically from the root yam "to sustain, support" and the -tra suffix expressing instruments. The literal meaning is still evident in the medical terminology of Sushruta, where the term refers to blunt surgical instruments such as tweezers or a vice. The meaning of "mystical or occult diagram" arises in the medieval period (Kathasaritsagara, Pancharatra).[7]

Usage and meaning

Yantras are usually associated with a particular deity and are used for specific benefits, such as: for meditation; protection from harmful influences; development of particular powers; attraction of wealth or success, etc.[8] For instance, the Sivali yantra, used mainly in Southeast Asian Buddhism, is used for the attraction of wealth and good luck. They are often used in daily ritual worship at home or in temples, and sometimes worn as a talisman.[9]

As an aid to meditation (meditative painting), yantras represent the deity that is the object of meditation. These yantras emanate from the central point, the bindu. The yantra typically has several geometric shapes radiating concentrically from the center, including triangles, circles, hexagons, octagons, and symbolic lotus petals. The outside often includes a square representing the four cardinal directions, with doors to each of them. A popular form is the Sri Chakra, or Sri Yantra, which represents the goddess in her form as Tripura Sundari. Sri Chakra also includes a representation of Shiva, and is designed to show the totality of creation and existence, along with the user's own unity with the cosmos.[9]

Yantras can be on a flat surface or three dimensional. Yantras can be drawn or painted on paper, engraved on metal, or any flat surface. They tend to be smaller in size than the similar mandala, and traditionally use less color than mandalas.[10]

Occult yantras are used as good luck charms, to ward off evil, as preventative medicine, in exorcism, etc., by virtue of their magical power. When used as a talisman, the yantra is seen to represent a deity who can be called on at will by the user. They are traditionally consecrated and energized by a priest, including the use of mantras which are closely associated to the specific deity and yantra. Practitioners believe that a yantra that is not energized with mantra is lifeless.[9] In Sri Lankan Buddhism, it is required to have the yantra of the deity with us, once the deity has shown the acceptance of our prayer.

Gudrun Bühnemann classifies three general types of yantras based on their usage:

- Yantras that are used as foundation for ritual implements such as lamps, vessels, etc. These are typically simple geometric shapes upon which the implements are placed.

- Yantras used in regular worship, such as the Sri Yantra. These include geometric diagrams and are energized with mantras to the deity, and sometimes include written mantras in the design.

- Yantras used in specific desire-oriented rites. These yantras are often made on birch bark or paper, and can include special materials such as flowers, rice paste, ashes, etc.[10]

Structural elements and symbolism

A yantra comprises geometric shapes, images, and written mantra. Triangles and hexagrams are common, as are circles and lotuses of 4 to 1,000 petals. Saiva and Shakti yantras often feature the prongs of a trishula.[11]

- Mantra

- Yantras frequently include mantras written in Sanskrit.

- Use of colors in traditional yantra is entirely symbolic, and not merely decorative or artistic. Each color is used to denote ideas and inner states of consciousness. White/Red/Black is one of the most significant color combinations, representing the three qualities or gunas of nature (prakriti). White represents sattwa or purity; red represents rajas or the activating quality; black represents tamas or the quality of inertia. Specific colors also represent certain aspects of the goddess. Not all texts give the same colors for yantras. Aesthetics and artistry are meaningless in a yantra if they are not based on the symbolism of the colors and geometric shapes.[12]

- Bindu

- The central point of traditional yantras have a bindu or point, which represents the main deity associated with the yantra. The retinue of the deity is often represented in the geometric parts around the center. The bindu in a yantra may be represented by a dot or small circle, or may remain invisible. It represents the point from which all of creation emanates. Sometimes, as in the case of the Linga Bhairavi yantra, the bindu may be presented in the form of a linga.[13]

- Triangle

- Most Hindu yantras include triangles. Downward-pointing triangles represent the feminine aspect of God or Shakti, while upward-pointing triangles represent God's masculine aspect, as in Shiva.

- Hexagram

- Hexagrams as shown in yantras are two equilateral triangles intertwined, representing the union of male and female aspects of divinity, or Shiva and Shakti.

- Lotus

- Mandalas and yantras both frequently include lotus petals, which represent purity and transcendence. Eight-petaled lotuses are common, but lotuses in yantras can include 2, 4, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 32, 100, 1000 or more petals.

- Circle

- Many mandalas have three concentric circles in the center, representing manifestation.

- Outer square

- Many mandalas have an outer square or nested squares, representing the earth and the four cardinal directions. Often they include sacred doorways on each side of the square.

- Pentagram

- Yantras infrequently use a pentagram. Some yantras of Guhyakali have a pentagram, due to the number five being associated with Kali.

- Octagon

- Octagons are also infrequent in yantras, where they represent the eight directions.[11]

Yantra designs in modern times have deviated from the traditional patterns given in ancient texts and traditions. Designers in the west may copy design elements from Nepali/tantric imitations of yantras.[14]

Yantra tattooing

Yantra Tattooing or Sak Yuant (Thai: สักยันต์ RTGS: sak yan)[15] is a form of tattooing using yantra designs in Buddhism. It consists of sacred geometrical, animal and deity designs accompanied by Pali phrases that are said to offer power, protection, fortune, charisma and other benefits for the bearer. Sak yant designs are normally tattooed by ruesi, wicha practitioners, and Buddhist monks, traditionally with a metal rod sharpened to a point (called a khem sak).[16]

Yantra drawing

The world’s largest Sri Chakra, measuring 67,400 sq ft was drawn on ground in Cranbury, New Jersey under the guidance of Guru Karunamaya.[17]

Gallery

Yan Paet-thit, a Thai yantra tattoo

Yan Paet-thit, a Thai yantra tattoo Traditional engraved copper Sri Yantra

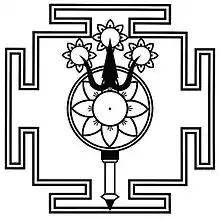

Traditional engraved copper Sri Yantra Yantra of Paramashiva, with trident

Yantra of Paramashiva, with trident The Sri Yantra diagram

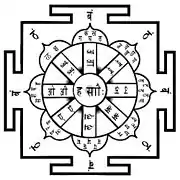

The Sri Yantra diagram Ashtamatrika yantra diagram

Ashtamatrika yantra diagram Tripurabhairava yantra diagram

Tripurabhairava yantra diagram

See also

- Mandala

- Kolam

- Rangoli

- Shri Yantra

- Sriramachakra

- Yantra tattooing

- Dayata meditation paintings

References

- "Recent entries into the dictionary". spokensanskrit.de. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017.

- Insoll, Professor of African and Islamic Archaeology Timothy; Insoll, Timothy (2002-09-11). Archaeology and World Religion. Routledge. ISBN 9781134597987.

- Harper, Katherine Anne; Brown, Robert L. (2012-02-01). Roots of Tantra, The. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791488904.

- "An Archaeologist at Work in African Prehistory and Early Human Studies: Teamwork and Insight". www.oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Kenoyer, J. M.; Clark, J. D.; Pal, J. N.; Sharma, G. R. (1983-07-01). "An upper palaeolithic shrine in India?". Antiquity. 57 (220): 88–94. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00055253. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 163969200.

- Khanna, Madhu (2003). Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity, page 21. Inner Traditions. ISBN 0-89281-132-3 & ISBN 978-0-89281-132-8

-

Monier-Williams, Monier (1899), A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Delhi

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). See also Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965), The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (Fourth revised and enlarged ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-0567-4: "1) that which restrains or fastens, any prop or support; 2) "a fetter", 4) any instrument or machine", [...] 7) "an amulet, a mystical or astronomical diagram used as an amulet"; White 1996, p. 481; - Denise Cush; Catherine Robinson; Michael York (21 August 2012). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Routledge. pp. 1028–1029. ISBN 978-1-135-18978-5.

- Khanna, Madhu (2005). "Yantra". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Gale's Encyclopedia of Religion (Second ed.). Thomson Gale. pp. 9871–9872. ISBN 0-02-865997-X.

- Gudrun Bühnemann (2003). Maònòdalas and Yantras in the Hindu Traditions. BRILL. pp. 30–35. ISBN 90-04-12902-2.

- Gudrun Bühnemann (2003). Maònòdalas and Yantras in the Hindu Traditions. BRILL. pp. 39–50. ISBN 90-04-12902-2.

- Khanna, Madhu (2003). Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity. pp. 132-133. Inner Traditions. ISBN 0-89281-132-3 & ISBN 978-0-89281-132-8

- "What Are Yantras and How Can They Benefit Me?". The Isha Blog. 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Gudrun Bühnemann (2003). Maònòdalas and Yantras in the Hindu Traditions. BRILL. p. 4. ISBN 90-04-12902-2.

- "สักยันต์". thai-language.com. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- "Sak Yant - Magic Tattoo | Thai Guide to Thailand". Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2021-04-13.

- "Projects". Soundarya Lahari Trust. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

Further reading

- Rana, Deepak (2012), Yantra, Mantra and Tantrism, USA: Neepradaka Press, ISBN 978-0-9564928-3-8

- Bucknell, Roderick; Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986), The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism, London: Curzon Press, ISBN 0-312-82540-4

- Khanna, Madhu (2003). Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity. Inner Traditions. ISBN 0-89281-132-3 & ISBN 978-0-89281-132-8

- White, David Gordon (1996), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-89499-1

External links

Quotations related to Yantra at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Yantra at Wikiquote Media related to Yantra at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yantra at Wikimedia Commons- web

.stanford .edu /class /history11sc /pdfs /yantra .pdf