Yeoman (household servant)

One of the earliest documented uses of Yeoman, it refers to a servant or attendant in a late Medieval English royal or noble household. A Yeoman was usually of higher rank in the household hierarchy. This hierarchy reflected the feudal society in which they lived. Everyone who served a royal or noble household knew their duties, and knew their place.[1] This was especially important when the household staff consisted of both nobles and commoners. There were actually two household hierarchies which existed in parallel. One was the organization based upon the function (duty) being performed. The other was based upon whether the person performing the duty was a noble or a commoner.[1]

_(late_15th_C)%252C_f.265v_-_BL_Royal_MS_14_E_IV.jpg.webp)

English Royal or noble household hierarchy

During the 14th century, the sizes of the royal households varied between 400 and 700 servants.[2] Similar household duties were grouped into Household Offices, which were then assigned to one of several Chief Officers. In the royal households of Edward II, Edward III, and Edward IV, the Chief Officers, and some of their responsibilities, were:[3][4][5]

- The Steward oversaw the Offices concerned with household management. Procurement, storage, and preparation of food, waiting at table, and tending to the kitchen gardens, were some of the duties for which the Steward was responsible.

- The Treasurer was responsible for the security of the King's treasury. This included tableware made of gold, silver, and precious stones, silver and gold-embroidered linens, as well as the Crown jewels.

- The Chamberlain supervised the personal service to the King. This included housekeeping in the royal chambers, and the day-to-day finances, such as purchases of foodstuffs, cloth, and other items.

- The Controller was responsible for the accounting of the bullion coin received and disbursed by the Treasury. Some of the coinage[6] was from tax levies and proceeds from the royal estates. Other coinage came from loans made by the Italian banks (such as Compagnia dei Bardi and Peruzzi) as additional capital for warfare.[7] And some of the coinage was received as ransom for noble prisoners of war,[8] (such as King John II of France).

- The Keeper of the Privy Seal was responsible for the King's small personal seal, which was used to validate letters issued by the King.[9]

Even from this small list of duties, it is evident that there were duties which only the nobility were entitled to perform. The Chief Officers were obviously nobles, and any duties which required close contact with the lord's immediate family, or their rooms, were handled by nobles.

.jpg.webp)

The servants were organized into a hierarchy which was arranged in ranks according to the level of responsibility.[1] The highest rank, which reported directly to the Chief Officer and oversaw an individual Household Office, was the Sergeant.[3] The word was introduced to England by the Normans, and meant an attendant or servant.[10] By the 15th century, the sergeants had acquired job titles which included their household office. Some examples are Sergeant of the Spicery, Sergeant of the Saucery, and Sergeant of the Chandlery.[10] The lowest rank of the Household Office was the Groom. First documented in Middle English, it meant a man-child or boy. When used in this sense as the lowest rank of a Household Office, it referred to a menial position for a free-born commoner.[11] A stable boy was one of these entry-level jobs. The modern meaning of groom as a stable hand who tends horses is derived from this usage.

Yeoman was the household rank between Sergeant and Groom.

Household Ordinances of King Edward III

One of the earliest contemporary references to yeoman is found in the Household Ordinances of King Edward III[12] written near the end of the English Late Middle Ages.

A Household Ordinance is a King's Proclamation itemizing everyone and everything he desires for his royal household. In modern terms, it is the King's budget submitted to the English Parliament, itemizing how the tax revenues allotted to the King would be spent. Any budget shortfalls were expected to be made up from either the King's revenues from the Crown lands, or loans from Italian bankers.[7] The Ordinance can contain, among other items, the number of members of his royal household and their duties.

Fortunately, two ordinances have survived from Edward III's reign which provide a glimpse into the King's Household during times of war as well as peace. They were recorded by Edward's Treasurer, Walter Wentwage. The 1344 Ordinance described the King's household that went with him to war in France. The 1347 Ordinance describes Edward's household after the Truce of Calais. Edward returned as the Black Death swept through France and into England.

In the 1344 Ordinance, there are two groups of yeomen listed: Yeomen of the King's Chamber and Yeomen of the Offices. Both groups are listed under Officers and ministers of the house with their retinue.[13] (Spellings have been modernized.) The separation into two groups seems to follow the contemporary social distinction between noble and common yeomen who share the same rank.[1] This same distinction is found in the 1347 Ordinance, where Yeomen of the King's chamber are contained in the same list with Yeomen of offices in household.[14]

Comparison of the two manuscripts reveals that Edward III had nine[13] Yeomen of the King's chamber while on campaign in France, and twelve[14] while he was home in England. Of the Yeomen of the Offices, Edward had seventy-nine,[13] and seventy[14] while in England.

Both the Yeomen of the King's chamber and the Yeomen of the Offices received the same wages. While on campaign, the yeomen received a daily wage of 6 pence.[15] Sixpence at the time was considered standard for 1 day's work by a skilled tradesman.[16] To compare with modern currency, the sixpence (half-shilling) in 1340 was worth between about £18.73-21.01[17] ($24.14-27.08 US) in 2017. A slightly different comparison is with the median household disposable income in Great Britain was £29,600[18] ($37,805 US) in 2019. Since the yeoman worked 7 days/per week, he would have earned between £6836-7669 ($8,730-11,072 US) per year in 2019 currency.

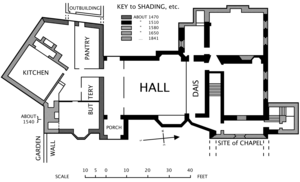

While serving his King at home, the yeomen received an annual salary of 13 s 4d, and an annual allowance of 4 s for his livery.[14] Livery was a symbol of the lord, conveying a sense of membership in the lord's house. The yeoman would be expected to wear it every day in the presence of the lord.[2] His rank entitled him to dine in the Great Hall.[2]

Functional title

By the reign of King Henry VI, some of the Household Yeomen had acquired job titles.[19] The Household Ordinance of King Henry VI,[20] written in 1455, listed the names of those yeomen with functional titles. The following is a partial list, arranged by the Office:[21]

- Office of the Kitchen

- Yeomen for the hall

- John Canne, Robert Litleboy, Richard Brigge

- Yeoman for the seating place

- Roger Sutton

- Yeomen for the hall

- Yeomen of the Crown

- Richard Clerk, Yeoman of the Armoury

- John Slytherst, Yeoman of the Robes

- Yeomen of the Chamber

- Henri Est, Yeoman of the Beds

- John Marchall, Yeoman Surgeon

- Stephen Coote, Yeoman Skinner

- Office of the Cellar

- William Wytnall, Yeoman for the bottles

An unusual-sounding job title was Yeoman for the King's Mouth. This was not a food taster for poison. Rather it applied to any job which required the handling of anything that touched the King's mouth: cups, bowls, table linen, bed linens etc. The Household Ordinance lists the following as Yeoman for the King's Mouth and the Office in which they worked:[22]

- William Pratte, Office of the Kitchen

- John Martyn, Office of the Lardery

- William Stoughton, Office of the Catery

- John Browne, Office of the Saucery

- John Penne, Office of the Ewery

- Thomas Laurence, Office of the Poultry

Black Book of the King's Household Edward IV

Detailed descriptions of the duties assigned to these and other yeomen in the Household Offices are given in Liber Niger Domus Regis Angliae Edw. IV (Black Book of the King's Household Edward IV).[23]

Yeomen of the Crown

These were 24 yeomen archers chosen from the best archers of all the lords of England for their "cunning and virtue", as well as for their manners and honesty.[24] The number of archers was a reminder of the 24 archers in Edward III's King's Watchmen. Four of the yeomen: Yeoman of the Wardrobe; Yeoman of the Wardrobe of Beds; and 2 Yeomen Ushers of the Chamber ate in the King's Chamber. The rest ate in the Great Hall with the Yeomen of the Household, except for the four great feasts (Christmastide, Eastertide, Whitsuntide, and Allhallowtide), when all the Yeomen ate in the King's Chamber. Additional duties were: Yeoman of the Stool; Yeoman of the Armory; Yeoman of the Bows for the King; Yeoman of the King's Books; and Yeoman of the King's Dogs. The Yeoman on night watch were armed with their swords (or other weapons) at the ready, and their harness (quiver) strapped to their shoulders.[25]

Office of the Ewery and Napery

The duty of serving the King's person was assigned to the Sergeant of the King's Mouth, who had a Yeoman and a Groom as his deputies.[26] Anything that touched the King's mouth at the dining table was considered their responsibility. The King's personal tableware (plates, cups, ewers, his personal eating utensils) made of precious metals and jewels, as well as his personal table linens (some were embroidered with silver or gold thread) were retrieved from the Household Treasurer. The Treasurer drew up a list of the valuable objects being withdrawn from the Royal Treasury, and each object was weighed before it was released to the Sergeant and/or his deputies. Whether the King dined in his Chamber or in the Great Hall, the Groom's duty was brush the tables clean, and cover them with the King's table linens, which were "wholesome, clean, and untouched" by strangers.[26] During the meal, the Sergeant attended the King with "clean basins and most pure waters" and towels untouched by strangers for cleansing his hands as needed.[26] If the Sergeant was away or not fit to appear at the King's table, the Yeoman would take his place. After the meal, the soiled linens were taken to the Office of the Lavendrey (Laundry), where they were carefully inspected and counted by both the Ewery deputies and those responsible for the King's Laundry. After being washed and dried, they were counted and inspected once again. The tableware was cleaned in the Ewery and returned to the Treasurer, where they were re-weighed to verify that no silver or gold had been removed. The table linen was closely inspected for any damage by the Treasurer. This traceability helped to discourage theft or intentional damage, as the servants were "upon pain of making good therefore, and for the lost pieces thereof."[27]

References

- Woolgar, C. M. (1999). The Great Household in Late Medieval England. London: Yale University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780300076875.

- Woolgar, C. M. (1999). The Great Household in Late Medieval England. London: Yale University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780300076875.

- Woolgar, C. M. (1999). The Great Household in Late Medieval England. London: Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780300076875.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 1-12. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 15-86. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Coinage". Richard II's treasure. University of London. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "The societies of the Bardi and the Peruzzi and their dealings with Edward III: (Ephraim Russell)". British History Online. University of London. 2019. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Ambühl, Rémy (2013). "Introduction". Prisoners of War in the Hundred Years War: Ransom Culture in the Late Middle Ages (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-1-107-01094-9.

- "Records of the Keeper of the Privy Seal". The National Archives. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Bradley, Henry, ed. (1914). "Sergeant". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 495. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Murray, James A. H., ed. (1901). "Groom". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 441. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 3. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 4. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 11. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Edward III". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 9. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- The National Archives. "Currency converter: 1270–2017". The National Archives. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- MeasuringWorth (2020). "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present". MeasuringWorth.com. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Office for National Statistics (5 March 2020). "Average household income, UK: financial year ending 2019". Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Onions, C. T., ed. (1928). "Yeoman". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Vol. 10, part 2 (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 40. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Henry VI". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 15. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Henry VI". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 17-21. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Household Ordinance of King Henry VI". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 20-22. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Liber Niger Domus Regis Edw. IV". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 15. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Liber Niger Domus Regis Edw. IV". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 38. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Liber Niger Domus Regis Edw. IV". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 38-9. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Liber Niger Domus Regis Edw. IV". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 83. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Society of Antiquaries, ed. (1790). "Liber Niger Domus Regis Edw. IV". A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household, made in divers reigns. London: John Nichols. p. 83-88. Retrieved 1 December 2020.