Yitro

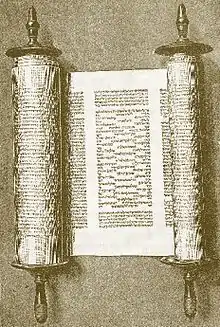

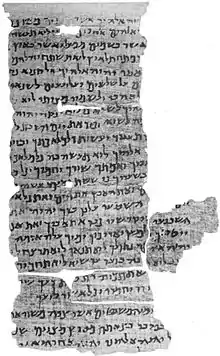

Yitro, Yithro, Yisroi, Yisrau, or Yisro (יִתְרוֹ, Hebrew for the name "Jethro," the second word and first distinctive word in the parashah) is the seventeenth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fifth in the Book of Exodus. The parashah tells of Jethro's organizational counsel to Moses and God's revelation of the Ten Commandments to the Israelites at Mount Sinai.

.jpg.webp)

The parashah constitutes Exodus 18:1–20:23. The parashah is the shortest of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Exodus and is also one of the shortest parashot in the Torah. It is made up of 4,022 Hebrew letters, 1,105 Hebrew words, and 75 verses.[1]

Jews read it the seventeenth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in January or February.[2] Jews also read part of the parashah, Exodus 19:1–20:23, as a Torah reading on the first day of the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, which commemorates the giving of the Ten Commandments.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading—Exodus 18:1–12

In the first reading, Moses' father-in-law Jethro heard all that God had done for the Israelites and brought Moses' wife Zipporah and her two sons Gershom ("I have been a stranger here") and Eliezer ("God was my help") to Moses in the wilderness at Mount Sinai.[4] Jethro rejoiced, blessed God, and offered sacrifices to God.[5]

Second reading—Exodus 18:13–23

In the second reading, the people stood from morning until evening waiting for Moses to adjudicate their disputes.[6] Jethro counseled Moses to make known the law, and then choose capable, trustworthy, God-fearing men to serve as chiefs to judge the people, bringing only the most difficult matters to Moses.[7]

Third reading—Exodus 18:24–27

In the short third reading, Moses heeded Jethro's advice.[8] Then Moses bade Jethro farewell, and Jethro went home.[9]

Fourth reading—Exodus 19:1–6

In the fourth reading, three months to the day after the Israelites left Egypt, they entered the wilderness at the foot of Mount Sinai.[10] Moses went up Mount Sinai, and God told him to tell the Israelites that if they would obey God faithfully and keep God's covenant, they would be God's treasured possession, a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation.[11]

Fifth reading—Exodus 19:7–19

In the fifth reading, when Moses told the elders, all the people answered: "All that the Lord has spoken we will do!" and Moses brought the people's words back to God.[12] God instructed Moses to have the people stay pure, wash their clothes, and prepare for the third day, when God would come down in the sight of the people, on Mount Sinai.[13] God told Moses to set bounds around the mountain, threatening whoever touched the mountain with death, and Moses did so.[14]

At dawn of the third day, there was thunder, lightning, a dense cloud upon the mountain, and a very loud blast of the horn.[15] Moses led the people to the foot of the mountain.[16] Mount Sinai was all in smoke, the mountain trembled violently, the blare of the horn grew louder and louder, and God answered Moses in thunder.[17]

Sixth reading—Exodus 19:20–20:14

In the sixth reading, God came down on the top of Mount Sinai, and called Moses up.[18] God again commanded Moses to warn the people not to break through.[19]

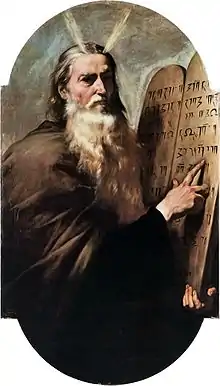

God spoke the Ten Commandments:

- "I the Lord am your God."[20]

- "You shall have no other gods besides Me. You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them."[21]

- "You shall not swear falsely by the name of the Lord your God."[22]

- "Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy."[23]

- "Honor your father and your mother."[24]

- "You shall not murder."

- "You shall not commit adultery."

- "You shall not steal."

- "You shall not bear false witness."[25]

- "You shall not covet . . . anything that is your neighbor's."[26]

Seventh reading—Exodus 20:15–23

In the seventh reading, seeing the thunder, lightning, and the mountain smoking, the people fell back and asked Moses to speak to them instead of God.[27] God told Moses to tell the people not make any gods of silver or gold, but an altar of earth for sacrifices.[28] God prohibited hewing the stones to make a stone altar.[29] And God prohibited ascending the altar by steps, so as not to exposed the priests' nakedness.[30]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading may read the parashah according to a different schedule. Some congregations that read the Torah according to the triennial cycle read the parashah in three divisions with the Ten Commandments in years two and three, while other congregations that read the Torah according to the triennial cycle nonetheless read the entire parashah with Ten Commandments every year.[31]

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Exodus chapter 20

The early third millennium BCE Sumerian wisdom text Instructions of Shuruppak contains maxims that parallel the Ten Commandments, including:

- Don't steal anything; don't kill yourself! . . .

- My son, don't commit murder . . .

- Don't laugh with a girl if she is married; the slander (arising from it) is strong! . . .

- Don't plan lies; it is discrediting . . .

- Don't speak fraudulently; in the end it will bind you like a trap.[32]

Noting that Sargon of Akkad was the first to use a seven-day week, Gregory Aldrete speculated that the Israelites may have adopted the idea from the Akkadian Empire.[33]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[34]

Exodus chapter 20

Exodus 34:28 and Deuteronomy 4:13 and 10:4 refer to the Ten Commandments as the "ten words" (עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, aseret ha-devarim).

The Sabbath

Exodus 20:8–11 refers to the Sabbath. Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[35]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God's work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

The Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:8–11 commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:12–15 commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work—so that one's subordinates might also rest—and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook, and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one's place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make them ride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people abstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God's Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God's fury upon them, but God stayed God's hand.

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

The Altar

Exodus 20:22, which prohibits building the altar from hewn stones, explaining that wielding tools upon the stones would profane them, is echoed by Deuteronomy 27:5–6, which prohibits wielding iron tools over the stones of the altar and requires that the Israelites build the altar from unhewn stones.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[36]

The Sabbath

1 Maccabees 2:27–38 told how in the 2nd century BCE, many followers of the pious Jewish priest Mattathias rebelled against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus's soldiers attacked a group of them on the Sabbath, and when the Pietists failed to defend themselves so as to honor the Sabbath (commanded in, among other places, Exodus 20:8–11, a thousand died. 1 Maccabees 2:39–41 reported that when Mattathias and his friends heard, they reasoned that if they did not fight on the Sabbath, they would soon be destroyed. So they decided that they would fight against anyone who attacked them on the Sabbath.[37]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[38]

Exodus chapter 18

The Tannaim debated what news Jethro heard in Exodus 18:1 that caused him to adopt the faith of Moses. Rabbi Joshua said that Jethro heard of the Israelites' victory over the Amalekites, as Exodus 17:13 reports the results of that battle immediately before Exodus 18:1 reports Jethro's hearing of the news. Rabbi Eleazar of Modim said that Jethro heard of the giving of the Torah, for when God gave Israel the Torah, the sound travelled from one end of the earth to the other, and all the world's kings trembled in their palaces and sang, as Psalm 29:9 reports, "The voice of the Lord makes the hinds to tremble . . . and in His temple all say: 'Glory.'" The kings then converged upon Balaam and asked him what the tumultuous noise was that they had heard—perhaps another flood, or perhaps a flood of fire. Balaam told them that God had a precious treasure in store, which God had hidden for 974 generations before the creation of the world, and God desired to give it to God's children, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength to His people." Immediately they all exclaimed the balance of Psalm 29:11: "The Lord will bless His people with peace." Rabbi Eleazar said that Jethro heard about the dividing of the Reed Sea, as Joshua 5:1 reports, "And it came to pass, when all the kings of the Amorites heard how the Lord had dried up the waters of the Jordan before the children of Israel," and Rahab the harlot too told Joshua's spies in Joshua 2:10: "For we have heard how the Lord dried up the water of the Red Sea."[39]

Rabbi Joshua interpreted Exodus 18:6 to teach that Jethro sent a messenger to Moses. Noting that Exodus 18:6 mentions each of Jethro, Zipporah, and Moses' children, Rabbi Eliezer taught that Jethro sent Moses a letter asking Moses to come out to meet Jethro for Jethro's sake; and should Moses be unwilling to do so for Jethro's sake, then to do so for the Zipporah's sake; and should Moses be reluctant to do so for her sake, then to do so the sake of Moses' children.[40]

Rabbi Pappias read the words "And Jethro said: 'Blessed be the Lord'" in Exodus 18:10 as a reproach to the Israelites, for not one of the 600,000 Israelites rose to bless God until Jethro did.[41]

Reading Exodus 18:13, "Moses sat to judge the people from the morning to the evening," the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael questioned whether Moses really sat as a judge that long. Rather, the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael suggested that the similarity of Exodus 18:13 to Genesis 1:15 taught that whoever renders a true judgment is accounted as a coworker with God in the work of creation. For Exodus 18:13 says, "from the morning to the evening," and Genesis 1:15 says, "And there was evening and there was morning."[42]

A Midrash expounded on the role of Moses as a judge in Exodus 18:13. Interpreting God's command in Exodus 28:1, the Sages told that when Moses came down from Mount Sinai, he saw Aaron beating the Golden Calf into shape with a hammer. Aaron really intended to delay the people until Moses came down, but Moses thought that Aaron was participating in the sin and was incensed with him. So God told Moses that God knew that Aaron's intentions were good. The Midrash compared it to a prince who became mentally unstable and started digging to undermine his father's house. His tutor told him not to weary himself but to let him dig. When the king saw it, he said that he knew the tutor's intentions were good, and declared that the tutor would rule over the palace. Similarly, when the Israelites told Aaron in Exodus 32:1, "Make us a god," Aaron replied in Exodus 32:1, "Break off the golden rings that are in the ears of your wives, of your sons, and of your daughters, and bring them to me." And Aaron told them that since he was a priest, they should let him make it and sacrifice to it, all with the intention of delaying them until Moses could come down. So God told Aaron that God knew Aaron's intention, and that only Aaron would have sovereignty over the sacrifices that the Israelites would bring. Hence in Exodus 28:1, God told Moses, "And bring near Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the children of Israel, that they may minister to Me in the priest's office." The Midrash told that God told this to Moses several months later in the Tabernacle itself when Moses was about to consecrate Aaron to his office. Rabbi Levi compared it to the friend of a king who was a member of the imperial cabinet and a judge. When the king was about to appoint a palace governor, he told his friend that he intended to appoint the friend's brother. So God made Moses superintendent of the palace, as Numbers 7:7 reports, "My servant Moses is . . . is trusted in all My house," and God made Moses a judge, as Exodus 18:13 reports, "Moses sat to judge the people." And when God was about to appoint a High Priest, God notified Moses that it would be his brother Aaron.[43]

Rabbi Berekiah taught in the name of Rabbi Ḥanina that judges must possess seven qualities, and Exodus 18:21 enumerates four: "Moreover you shall provide out of all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating unjust gain." And Deuteronomy 1:13 mentions the other three: They must be "wise men, and understanding, and full of knowledge." Scripture does not state all seven qualities together to teach that if people possessing all the seven qualities are not available, then those possessing four are selected; if people possessing four qualities are not available, then those possessing three are selected; and if even these are not available, then those possessing one quality are selected, for as Proverbs 31:10 says, "A woman of valor who can find?"[44]

.jpg.webp)

Exodus chapter 19

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael deduced from the use of the singular form of the verb "encamped" (vayichan, וַיִּחַן) in Exodus 19:2 that all the Israelites agreed and were of one mind.[45]

Noting that Exodus 19:2 reports, "they encamped in the desert," the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that the Torah was given openly, in a public place, for if it had been given in the Land of Israel, the Israelites could say to the nations of the world that they had no portion in it. But it was given openly, in a public place, and all who want to take it may come and take it. It was not given at night, as Exodus 19:16 reports, "And it was on the third day, when it was morning . . . ." It was not given in silence, as Exodus 19:16 reports, "and there were thunders and lightnings." It was not given inaudibly, as Exodus 20:15 reports, "And all the people saw the thunders and the lightnings."[46]

A Midrash taught that God created the world so that the upper realms should be for the upper beings, and the lower realms for the lower, as Psalm 115:16 says, "The heavens are the heavens of the Lord, but the earth has He given to the children of men." Then Moses changed the earthly into heavenly and the heavenly into earthly, for as Exodus 19:3 reports, "Moses went up to God," and then Exodus 19:20 reports, "The Lord came down upon Mount Sinai."[47]

Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the words, "And how I bore you on eagles' wings," in Exodus 19:4 to teach that God rapidly gathered all the Israelites and brought them to Rameses.[48] And the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael further deduced from Exodus 19:4 that the Israelites traveled from Rameses to Succoth in the twinkling of an eye.[49]

.jpg.webp)

Reading the words, "And how I bore you on eagles' wings," in Exodus 19:4, the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that eagles differ from all other birds because other birds carry their young between their feet, being afraid of other birds flying higher above them. Eagles, however, fear only people who might shoot arrows at them from below. Eagles, therefore, prefer that the arrows hit them rather than their children. The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael compared this to a man who walked on the road with his son in front of him. If robbers, who might seek to capture his son, come from in front, the man puts his son behind him. If a wolf comes from behind, the man puts his son in front of him. If robbers come from in front and wolves from behind, the man puts his son on his shoulders. As Deuteronomy 1:31 says, "You have seen how the Lord your God bore you, as a man bears his son."[50]

Reading Exodus 19:4, a Midrash taught that God did not conduct God's Self with the Israelites in the usual manner. For usually when one acquired servants, it was on the understanding that the servants drew the master's carriage. God, however, did not do so, for God bore the Israelites, for in Exodus 19:4, God says to the Israelites, "I bore you on eagles' wings."[51]

A Midrash likened God to a bridegroom and Israel to a bride, and taught that Exodus 19:10 reports that God betrothed Israel at Sinai. The Midrash noted that the Rabbis taught that documents of betrothal and marriage are written only with the consent of both parties, and the bridegroom pays the scribe's fee.[52] The Midrash then taught that God betrothed Israel at Sinai, reading Exodus 19:10 to say, "And the Lord said to Moses: 'Go to the people and betroth them today and tomorrow.'" The Midrash taught that in Deuteronomy 10:1, God commissioned Moses to write the document, when God directed Moses, "Carve two tables of stone." And Deuteronomy 31:9 reports that Moses wrote the document, saying, "And Moses wrote this law." The Midrash then taught that God compensated Moses for writing the document by giving him a lustrous countenance, as Exodus 34:29 reports, "Moses did not know that the skin of his face sent forth beams."[53]

In the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Ḥanina told that in the third month, the day is double the night, and the Israelites slept until two hours of the day, for sleep on the day of the feast of Shavuot is pleasant, as the night is short. Moses went to the camp and aroused the Israelites from their sleep, for God desired to give them the Torah. Exodus 19:17 says, "And Moses brought forth the people out of the camp to meet God," and God also went forth to meet them, like a bridegroom who goes forth to meet his bride.[54]

The Mishnah noted that oxen were the same as all other beasts insofar as they were required by Exodus 19:12–13 to keep away from Mount Sinai.[55]

The Gemara cited Exodus 19:15 to explain how Moses decided to abstain from marital relations so as to remain pure for his communication with God. A Baraita taught that Moses did three things of his own understanding, and God approved: (1) Moses added one day of abstinence of his own understanding; (2) he separated himself from his wife (entirely, after the Revelation); and (3) he broke the Tablets of Stone (on which God had written the Ten Commandments). The Gemara explained that to reach his decision to separate himself from his wife, Moses applied an a fortiori (kal va-chomer) argument to himself. Moses noted that even though the Shechinah spoke with the Israelites on only one definite, appointed time (at Mount Sinai), God nonetheless instructed in Exodus 19:15, "Be ready against the third day: come not near a woman." Moses reasoned that if he heard from the Shechinah at all times and not only at one appointed time, how much more so should he abstain from marital contact. And the Gemara taught that we know that God approved, because in Deuteronomy 5:27, God instructed Moses (after the Revelation at Sinai), "Go say to them, 'Return to your tents'" (thus giving the Israelites permission to resume marital relations) and immediately thereafter in Deuteronomy 5:28, God told Moses, "But as for you, stand here by me" (excluding him from the permission to return). And the Gemara taught that some cite as proof of God's approval God's statement in Numbers 12:8, "with him [Moses] will I speak mouth to mouth" (as God thus distinguished the level of communication God had with Moses, after Miriam and Aaron had raised the marriage of Moses and then questioned the distinctiveness of the prophecy of Moses).[56]

The Mishnah deduced from Exodus 19:15 that a woman who emits semen on the third day after intercourse is unclean.[57]

The Rabbis compared the Israelites' encounter at Sinai to Jacob's dream in Genesis 28:12–13. The "ladder" in Jacob's dream symbolizes Mount Sinai. That the ladder is "set upon (מֻצָּב, mutzav) the earth" recalls Exodus 19:17, which says, "And they stood (וַיִּתְיַצְּבוּ, vayityatzvu) at the nether part of the mount." The words of Genesis 28:12, "and the top of it reached to heaven," echo those of Deuteronomy 4:11, "And the mountain burned with fire to the heart of heaven." "And behold the angels of God" alludes to Moses and Aaron. "Ascending" parallels Exodus 19:3: "And Moses went up to God." "And descending" parallels Exodus 19:14: "And Moses went down from the mount." And the words "and, behold, the Lord stood beside him" in Genesis 28:13 parallel the words of Exodus 19:20: "And the Lord came down upon Mount Sinai."[58]

Rabbi Levi addressed the question that Deuteronomy 4:33 raises: "Did ever a people hear the voice of God speaking out of the midst of the fire, as you have heard, and live?" (Deuteronomy 4:33, in turn, refers back to the encounter at Sinai reported at Exodus 19:18–19, 20:1, and after.) Rabbi Levi taught that the world would not have been able to survive hearing the voice of God in God's power, but instead, as Psalm 29:4 says, "The voice of the Lord is with power." That is, the voice of God came according to the power of each individual—young, old, or infant—to receive it.[59]

Reading the words "And the Lord came down upon mount Sinai, to the top of the mount" in Exodus 19:20, the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael supposed that one might think that God actually descended from heaven and transferred God's Presence to the mountain. Thus the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael noted that Exodus 20:19 says: "You yourselves have seen that I have talked with you from heaven," and deduced that God bent down the heavens, lowering them to the top of the mountain, and spread the heavens as a person spreads a mattress on a bed, and spoke from the heavens as a person would speak from the top of a mattress.[60]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that when Moses ascended on high (as Exodus 19:20 reports), the ministering angels asked God what business one born of woman had among them. God told them that Moses had come to receive the Torah. The angels questioned why God was giving to flesh and blood the secret treasure that God had hidden for 974 generations before God created the world. The angels asked, in the words of Psalm 8:8, "What is man, that You are mindful of him, and the son of man, that You think of him?" God told Moses to answer the angels. Moses asked God what was written in the Torah. In Exodus 20:2, God said, "I am the Lord your God, Who brought you out of the Land of Egypt." So Moses asked the angels whether the angels had gone down to Egypt or were enslaved to Pharaoh. As the angels had not, Moses asked them why then God should give them the Torah. Again, Exodus 20:3 says, "You shall have no other gods," so Moses asked the angels whether they lived among peoples that engage in idol worship. Again, Exodus 20:8 says, "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy," so Moses asked the angels whether they performed work from which they needed to rest. Again, Exodus 20:7 says, "You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain," so Moses asked the angels whether there were any business dealings among them in which they might swear oaths. Again, Exodus 20:12 says, "Honor your father and your mother," so Moses asked the angels whether they had fathers and mothers. Again, Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not murder; you shall not commit adultery; you shall not steal," so Moses asked the angels whether there was jealousy among them and whether the Evil Tempter was among them. Immediately, the angels conceded that God's plan was correct, and each angel felt moved to love Moses and give him gifts. Even the Angel of Death confided his secret to Moses, and that is how Moses knew what to do when, as Numbers 17:11–13 reports, Moses told Aaron what to do to make atonement for the people, to stand between the dead and the living, and to check the plague.[61]

Exodus chapter 20

In the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Tarfon taught that God came from Mount Sinai (or others say Mount Seir) and was revealed to the children of Esau, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them," and "Seir" means the children of Esau, as Genesis 36:8 says, "And Esau dwelt in Mount Seir." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall do no murder." The children of Esau replied that they were unable to abandon the blessing with which Isaac blessed Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword shall you live." From there, God turned and was revealed to the children of Ishmael, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "He shined forth from Mount Paran," and "Paran" means the children of Ishmael, as Genesis 21:21 says of Ishmael, "And he dwelt in the wilderness of Paran." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall not steal." The children of Ishmael replied that they were unable to abandon their fathers' custom, as Joseph said in Genesis 40:15 (referring to the Ishmaelites' transaction reported in Genesis 37:28), "For indeed I was stolen away out of the land of the Hebrews." From there, God sent messengers to all the nations of the world asking them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:3 and Deuteronomy 5:7), "You shall have no other gods before me." They replied that they had no delight in the Torah, therefore let God give it to God's people, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength [identified with the Torah] to His people; the Lord will bless His people with peace." From there, God returned and was revealed to the children of Israel, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "And he came from the ten thousands of holy ones," and the expression "ten thousands" means the children of Israel, as Numbers 10:36 says, "And when it rested, he said, 'Return, O Lord, to the ten thousands of the thousands of Israel.'" With God were thousands of chariots and 20,000 angels, and God's right hand held the Torah, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At his right hand was a fiery law to them."[62]

Reading Exodus 20:1, "And God spoke all these words, saying," the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that God spoke the ten commandments in one utterance, in a manner of speech of which human beings are incapable.[63]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that with every single word that God spoke (as Exodus 20:1 reports), the Israelites' souls departed, as Song of Songs 5:6 says: "My soul went forth when He spoke." But if their souls departed at the first word, how could they receive the second word? God revived them with the dew with which God will resurrect the dead, as Psalm 68:10 says, "You, O God, did send a plentiful rain; You did confirm your inheritance, when it was weary." Rabbi Joshua ben Levi also taught that with every word that God spoke, the Israelites retreated a distance of 12 mils, but the ministering angels led them back, as Psalm 68:13 says, "The hosts of angels march, they march (יִדֹּדוּן יִדֹּדוּן, yiddodun yiddodun)." Instead of yiddodun ("they march"), Rabbi Joshua ben Levi read yedaddun ("they lead").[64]

Rabbi Abbahu said in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan that when God gave the Torah, no bird twittered, no fowl flew, no ox lowed, none of the Ophanim stirred a wing, the Seraphim did not say (in the words of Isaiah 6:3) "Holy, Holy," the sea did not roar, the creatures did not speak, the whole world was hushed into breathless silence and the voice went forth in the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6: "I am the Lord your God."[65]

Rabbi Levi explained that God said the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6, "I am the Lord your God," to reassure Israel that just because they heard many voices at Sinai, they should not believe that there are many deities in heaven, but rather they should know that God alone is God.[59]

Rabbi Tobiah bar Isaac read the words of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6, "I am the Lord your God," to teach that it was on the condition that the Israelites acknowledged God as their God that God (in the continuation of Exodus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 5:6) "brought you out of the land of Egypt." And a Midrash compared "I am the Lord your God" to a princess who having been taken captive by robbers, was rescued by a king, who subsequently asked her to marry him. Replying to his proposal, she asked what dowry the king would give her, to which the king replied that it was enough that he had rescued her from the robbers. (So God's delivery of the Israelites from Egypt was enough reason for the Israelites to obey God's commandments.)[66]

Rabbi Levi said that the section beginning at Leviticus 19:1 was spoken in the presence of the whole Israelite people, because it includes each of the Ten Commandments, noting that: (1) Exodus 20:2 says, "I am the Lord your God," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "I am the Lord your God"; (2) Exodus 20:2–3 says, "You shall have no other gods," and Leviticus 19:4 says, "Nor make to yourselves molten gods"; (3) Exodus 20:7 says, "You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain," and Leviticus 19:12 says, "And you shall not swear by My name falsely"; (4) Exodus 20:8 says, "Remember the Sabbath day," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "And you shall keep My Sabbaths"; (5) Exodus 20:12 says, "Honor your father and your mother," and Leviticus 19:3 says, "You shall fear every man his mother, and his father"; (6) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not murder," and Leviticus 19:16 says, "Neither shall you stand idly by the blood of your neighbor"; (7) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not commit adultery," and Leviticus 20:10 says, "Both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to death; (8) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not steal," and Leviticus 19:11 says, "You shall not steal"; (9) Exodus 20:13 says, "You shall not bear false witness," and Leviticus 19:16 says, "You shall not go up and down as a talebearer"; and (10) Exodus 20:14 says, "You shall not covet . . . anything that is your neighbor's," and Leviticus 19:18 says, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself."[67]

The Mishnah taught that the priests recited the Ten Commandments daily.[68] The Gemara, however, taught that although the Sages wanted to recite the Ten Commandments along with the Shema in precincts outside of the Temple, they soon abolished their recitation, because the Sages did not want to lend credence to the arguments of the heretics (who might argue that Jews honored only the Ten Commandments).[69]

.jpg.webp)

Rabbi Ishmael interpreted Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:6–7 to be the first of the Ten Commandments. Rabbi Ishmael taught that Scripture speaks in particular of idolatry, for Numbers 15:31 says, "Because he has despised the word of the Lord." Rabbi Ishmael interpreted this to mean that an idolater despises the first word among the Ten Words or Ten Commandments in Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:6–7, "I am the Lord your God . . . . You shall have no other gods before Me."[70]

The Gemara taught that the Israelites heard the words of the first two commandments (in Exodus 20:3–6 and Deuteronomy 5:7–10) directly from God. Rabbi Simlai expounded that a total of 613 commandments were communicated to Moses—365 negative commandments, corresponding to the number of days in the solar year, and 248 positive commandments, corresponding to the number of the parts in the human body. Rav Hamnuna said that one may derive this from Deuteronomy 33:4, "Moses commanded us Torah, an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob." The letters of the word "Torah" (תּוֹרָה) have a numerical value of 611 (as ת equals 400, ו equals 6, ר equals 200, and ה equals 5). And the Gemara did not count among the commandments that the Israelites heard from Moses the commandments, "I am the Lord your God," and, "You shall have no other gods before Me," as the Israelites heard those commandments directly from God.[71]

The Sifre taught that to commit idolatry is to deny the entire Torah.[72]

Tractate Avodah Zarah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws prohibiting idolatry in Exodus 20:3–6 and Deuteronomy 5:7–10.[73]

The Mishnah taught that those who engaged in idol worship were executed, whether they served it, sacrificed to it, offered it incense, made libations to it, prostrated themselves to it, accepted it as a god, or said to it "You are my god." But those who embraced, kissed, washed, anointed, clothed, or swept or sprinkled the ground before an idol merely transgressed the negative commandment of Exodus 20:5 and were not executed.[74]

The Gemara reconciled apparently discordant verses touching on vicarious responsibility. The Gemara noted that Deuteronomy 24:16 states: "The fathers shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the fathers; every man shall be put to death for his own sin," but Exodus 20:5 says: "visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children." The Gemara cited a Baraita that interpreted the words "the iniquities of their fathers shall they pine away with them" in Leviticus 26:39 to teach that God punishes children only when they follow their parents' sins. The Gemara then questioned whether the words "they shall stumble one upon another" in Leviticus 26:37 do not teach that one will stumble through the sin of the other, that all are held responsible for one another. The Gemara answered that the vicarious responsibility of which Leviticus 26:37 speaks is limited to those who have the power to restrain their fellow from evil but do not do so.[75]

Tractates Nedarim and Shevuot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of vows and oaths in Exodus 20:7, Leviticus 5:1–10 and 19:12, Numbers 30:2–17, and Deuteronomy 23:24.[76]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:8–11; 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:12.[77]

The Mishnah interpreted the prohibition of animals working in Exodus 20:10 to teach that on the Sabbath, animals could wear their tethers, and their caretakers could lead them by their tethers and sprinkle or immerse them with water.[78] The Mishnah taught that a donkey could go out with a saddle cushion tied to it, rams strapped, ewes covered, and goats with their udders tied. Rabbi Jose forbade all these, except covering ewes. Rabbi Judah allowed goats to go out with their udders tied to dry, but not to save their milk.[79] The Mishnah taught that animals could not go out with a pad tied to their tails. A driver could not tie camels together and pull one of them, but a driver could take the leads of several camels in hand and pull them.[80] The Mishnah prohibited donkeys with untied cushions, bells, ladder–shaped yokes, or thongs around their feet; fowls with ribbons or leg straps; rams with wagons; ewes protected by wood chips in their noses; calves with little yokes; and cows with hedgehog skins or straps between their horns. The Mishnah reported that Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah's cow used to go out with a thong between its horns, but without the consent of the Rabbis.[81]

The Gemara reported that on the eve of the Sabbath before sunset, Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai and his son saw an old man running with two bundles of myrtle and asked him what they were for. The old man explained that they were to bring a sweet smell to his house in honor of the Sabbath. Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai asked whether one bundle would not be enough. The old man replied that one bundle was for "Remember" in Exodus 20:8 and one was for "Observe" in Deuteronomy 5:12. Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai told his son to mark how precious the commandments are to Israel.[82]

A Midrash cited the words of Exodus 20:10, "And your stranger who is within your gates," to show God's injunction to welcome the stranger. The Midrash compared the admonition in Isaiah 56:3, "Neither let the alien who has joined himself to the Lord speak, saying: 'The Lord will surely separate me from his people.'" (Isaiah enjoined Israelites to treat the convert the same as a native Israelite.) Similarly, the Midrash quoted Job 31:32, in which Job said, "The stranger did not lodge in the street" (that is, none were denied hospitality), to show that God disqualifies no creature, but receives all; the city gates were open all the time and anyone could enter them. The Midrash equated Job 31:32, "The stranger did not lodge in the street," with the words of Exodus 20:10, Deuteronomy 5:14, and Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates" (which implies that strangers were integrated into the midst of the community). Thus the Midrash taught that these verses reflect the Divine example of accepting all creatures.[83]

A Midrash employed the words of Exodus 20:10, Deuteronomy 5:14, and Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates," to reconcile the command of Exodus 12:43, "And the Lord said to Moses and Aaron: 'This is the ordinance of the Passover: No alien shall eat thereof," with the admonition of Isaiah 56:3, "Neither let the alien who has joined himself to the Lord speak, saying: 'The Lord will surely separate me from his people.'" (Isaiah enjoins us to treat the convert the same as a native Israelite.) The Midrash quoted Job 31:32, in which Job said, "The stranger did not lodge in the street" (that is, none were denied hospitality), to show that God disqualifies no one, but receives all; the city gates were open all the time and anyone could enter them. The Midrash equated Job 31:32, "The stranger did not lodge in the street," with the words of Exodus 20:10, Deuteronomy 5:14, and Deuteronomy 31:12, "And your stranger who is within your gates," which imply that strangers were integrated into the community. Thus, these verses reflect the Divine example of accepting all. Rabbi Berekiah explained that in Job 31:32, Job said, "The stranger did not lodge in the street," because strangers will one day be ministering priests in the Temple, as Isaiah 14:1 says: "And the stranger shall join himself with them, and they shall cleave (וְנִסְפְּחוּ, venispechu) to the house of Jacob," and the word "cleave" (וְנִסְפְּחוּ, venispechu) always refers to priesthood, as 1 Samuel 2:36 says, "Put me (סְפָחֵנִי, sefacheini), I pray you, into one of the priests' offices." The Midrash taught that strangers will one day partake of the showbread, because their daughters will be married into the priesthood.[83]

Rav Judah taught in Rav's name that the words of Deuteronomy 5:12, "Observe the Sabbath day . . . as the Lord your God commanded you" (in which Moses used the past tense for the word "commanded," indicating that God had commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath before the revelation at Mount Sinai) indicate that God commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath when they were at Marah, about which Exodus 15:25 reports, "There He made for them a statute and an ordinance."[84]

The Mishnah taught that every act that violates the law of the Sabbath also violates the law of a festival, except that one may prepare food on a festival but not on the Sabbath.[85]

The Tanna Devei Eliyahu taught that if you live by the commandment establishing the Sabbath (in Exodus 20:8 and Deuteronomy 5:12), then (in the words of Isaiah 62:8) "The Lord has sworn by His right hand, and by the arm of His strength: 'Surely I will no more give your corn to be food for your enemies." If, however, you transgress the commandment, then it will be as in Numbers 32:10–11, when "the Lord's anger was kindled in that day, and He swore, saying: 'Surely none of the men . . . shall see the land.'"[86]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed—the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[87]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[88]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Mishnah taught that both men and women are obligated to carry out all commandments concerning their fathers.[89] Rav Judah interpreted the Mishnah to mean that both men and women are bound to perform all precepts concerning a father that are incumbent upon a son to perform for his father.[90]

A Midrash noted that almost everywhere, Scripture mentions a father's honor before the mother's honor. (See, for example, Exodus 20:12, Deuteronomy 5:16, 27:16.) But Leviticus 19:3 mentions the mother first to teach that one should honor both parents equally.[91]

It was taught in a Baraita that Judah the Prince said that God knows that a son honors his mother more than his father, because the mother wins him over with words. Therefore, (in Exodus 20:12) God put the honor of the father before that of the mother. God knows that a son fears his father more than his mother, because the father teaches him Torah. Therefore, (in Leviticus 19:3) God put the fear of the mother before that of the father.[92]

Our Rabbis taught in a Baraita what it means to "honor" and "revere" one's parents within the meaning of Exodus 20:12 (honor), Leviticus 19:3 (revere), and Deuteronomy 5:16 (honor). To "revere" means that the child must neither stand nor sit in the parent's place, nor contradict the parent's words, nor engage in a dispute to which the parent is a party. To "honor" means that the child must give the parent food and drink and clothes, and take the parent in and out.[93]

Noting that Exodus 20:12 commands, "Honor your father and your mother," and Proverbs 3:9 directs, "Honor the Lord with your substance," the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Scripture thus likens the honor due to parents to that due to God. Similarly, as Leviticus 19:3 commands, "You shall fear your father and mother," and Deuteronomy 6:13 commands, "The Lord your God you shall fear and you shall serve," Scripture likens the fear of parents to the fear of God. And as Exodus 21:17 commands, "He that curses his father or his mother shall surely be put to death," and Leviticus 24:15 commands, "Whoever curses his God shall bear his sin," Scripture likens cursing parents to cursing God. But the Baraita conceded that with respect to striking (which Exodus 21:15 addresses with regard to parents), that it is certainly impossible (with respect to God). The Baraita concluded that these comparisons between parents and God are only logical, since the three (God, the mother, and the father) are partners in creation of the child. For the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that there are three partners in the creation of a person—God, the father, and the mother. When one honors one's father and mother, God considers it as if God had dwelt among them and they had honored God. And a Tanna taught before Rav Naḥman that when one vexes one's father and mother, God considers it right not to dwell among them, for had God dwelt among them, they would have vexed God.[94]

Chapter 9 of Tractate Sanhedrin in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of murder in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17.[95] The Mishnah taught that one who intended to kill an animal but killed a person instead was not liable for murder. One was not liable for murder who intended to kill an unviable fetus and killed a viable child. One was not liable for murder who intended to strike the victim on the loins, where the blow was insufficient to kill, but struck the heart instead, where it was sufficient to kill, and the victim died. One was not liable for murder who intended to strike the victim on the heart, where it was enough to kill, but struck the victim on the loins, where it was not, and yet the victim died.[96]

Interpreting the consequences of murder (prohibited in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), the Mishnah taught that God created the first human (Adam) alone to teach that Scripture imputes guilt to one who destroys a single soul of Israel as though that person had destroyed a complete world, and Scripture ascribes merit to one who preserves a single soul of Israel as though that person had preserved a complete world.[97]

The Tanna Devei Eliyahu taught that if you live by the commandment prohibiting murder (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), then (in the words of Leviticus 26:6) "the sword shall not go through your land." If, however, you transgress the commandment, then (in God's words in Leviticus 26:33) "I will draw out the sword after you."[98]

Rabbi Josiah taught that we learn the formal prohibition against kidnapping from the words "You shall not steal" in Exodus 20:13 (since Deuteronomy 22:7 and Exodus 21:16 merely state the punishment for abduction). Rabbi Joḥanan taught that we learn it from Leviticus 25:42, "They shall not be sold as bondsmen." The Gemara harmonized the two positions by concluding that Rabbi Josiah referred to the prohibition for abduction, while Rabbi Joḥanan referred to the prohibition for selling a kidnapped person. Similarly, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Exodus 20:13, "You shall not steal," refers to the stealing of human beings. To the potential objection that Exodus 20:13 refers to property theft, the Baraita responded that one of the thirteen principles by which we interpret the Torah is that a law is interpreted by its general context, and the Ten Commandments speak of capital crimes (like murder and adultery). (Thus "You shall not steal" must refer to a capital crime and thus to kidnapping.) Another Baraita taught that the words "You shall not steal" in Leviticus 19:11 refer to theft of property. To the potential objection that Leviticus 19:11 refers to the theft of human beings, the Baraita responded that the general context of Leviticus 19:10–15 speaks of money matters; therefore Leviticus 19:11 must refer to monetary theft.[99]

.jpg.webp)

According to the Mishnah, if witnesses testified that a person was liable to receive 40 lashes, and the witnesses turned out to have perjured themselves, then Rabbi Meir taught that the perjurers received 80 lashes—40 on account of the commandment of Exodus 20:13 not to bear false witness and 40 on account of the instruction of Deuteronomy 19:19 to do to perjurers as they intended to do to their victims—but the Sages said that they received only 40 lashes.[100]

Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish taught that the commandment of Exodus 20:13 not to bear false witness included every case of false testimony.[101]

Rav Aha of Difti said to Ravina that one can transgress the commandment not to covet in Exodus 20:14 and Deuteronomy 5:18 even in connection with something for which one is prepared to pay.[102]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael asked whether the commandment not to covet in Exodus 20:14 applied so far as to prohibit merely expressing one's desire for one's neighbor's things in words. But the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael noted that Deuteronomy 7:25 says, "You shall not covet the silver or the gold that is on them, nor take it for yourself." And the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael reasoned that just as in Deuteronomy 7:25 the word "covet" applies only to prohibit the carrying out of one's desire into practice, so also Exodus 20:14 prohibits only the carrying out of one's desire into practice.[103]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon distinguished the prohibition of Exodus 20:14, "You shall not covet," from that of Deuteronomy 5:18, "neither shall you desire." The Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon taught that the differing terms mean that one can incur liability for desiring in and of itself and for coveting in and of itself.[104]

Rabbi Ishmael interpreted the words "all the people perceived the thunderings, and the lightnings, and the voice of the horn" in Exodus 20:15 to mean that the people saw what could be seen and heard what could be heard. But Rabbi Akiva said that they saw and heard what was perceivable, and they saw the fiery word of God strike the tablets.[105]

The Gemara taught that Exodus 20:17 sets forth one of the three most distinguishing virtues of the Jewish People. The Gemara taught that David told the Gibeonites that the Israelites are distinguished by three characteristics: They are merciful, bashful, and benevolent. They are merciful, for Deuteronomy 13:18 says that God would "show you (the Israelites) mercy, and have compassion upon you, and multiply you." They are bashful, for Exodus 20:17 says "that God's fear may be before you (the Israelites)." And they are benevolent, for Genesis 18:19 says of Abraham "that he may command his children and his household after him, that they may keep the way of the Lord, to do righteousness and justice." The Gemara taught that David told the Gibeonites that only one who cultivates these three characteristics is fit to join the Jewish People.[106]

A Midrash likened the commandment of Deuteronomy 25:15 to have just weights and measures to that of Exodus 20:20 not to make gods of silver, or gods of gold. Reading Deuteronomy 25:15, Rabbi Levi taught that blessed actions bless those who are responsible for them, and cursed actions curse those who are responsible for them. The Midrash interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 25:15, "A perfect and just weight you shall have," to mean that if one acts justly, one will have something to take and something to give, something to buy and something to sell. Conversely, the Midrash read Deuteronomy 25:13–14 to teach, "You shall not have possessions if there are in your bag diverse weights, a great and a small. You shall not have possessions if there are in your house diverse measures, a great and a small." Thus, if one does employ deceitful measures, one will not have anything to take or give, to buy or sell. The Midrash taught that God tells businesspeople that they "may not make" one measure great and another small, but if they do, they "will not make" a profit. The Midrash likened this commandment to that of Exodus 20:20, "You shall not make with Me gods of silver, or gods of gold, you shall not make," for if a person did make gods of silver and gold, then that person would not be able to afford to have even gods of wood or stone.[107]

The Mishnah told that the stones of the Temple's altar and ramp came from the valley of Beit Kerem. When retrieving the stones, they dug virgin soil below the stones and brought whole stones that iron never touched, as required by Exodus 20:22 and Deuteronomy 27:5–6, because iron rendered stones unfit for the altar just by touch. A stone was also unfit if it was chipped through any means. They whitewashed the walls and top of the altar twice a year, on Passover and Sukkot, and they whitewashed the vestibule once a year, on Passover. Rabbi (Judah the Patriarch) said that they cleaned them with a cloth every Friday because of blood stains. They did not apply the whitewash with an iron trowel, out of the concern that the iron trowel would touch the stones and render them unfit, for iron was created to shorten humanity's days, and the altar was created to extend humanity's days, and it is not proper that that which shortens humanity's days be placed on that which extends humanity's days.[108]

The Tosefta reported that Rabban Joḥanan ben Zakkai said that Deuteronomy 27:5 singled out iron, of all metals, to be invalid for use in building the altar because one can make a sword from it. The sword is a sign of punishment, and the altar is a sign of atonement. They thus kept that which is a sign of punishment away from that which is a sign of atonement. Because stones, which do not hear or speak, bring atonement between Israel and God, Deuteronomy 27:5 says, "you shall lift up no iron tool upon them." So children of Torah, who atone for the world—how much more should no force of injury come near to them.[109] Similarly, Deuteronomy 27:6 says, "You shall build the altar of the Lord your God of unhewn stones." Because the stones of the altar secure the bond between Israel and God, God said that they should be whole before God. Children of Torah, who are whole for all time—how much more should they be deemed whole (and not wanting) before God.[110]

The Mishnah deduced from Exodus 20:21 that even when only a single person sits occupied with Torah, the Shechinah is with the student.[111]

Rabbi Isaac taught that God reasoned that if God said in Exodus 20:21, "An altar of earth you shall make to Me [and then] I will come to you and bless you," thus revealing God's Self to bless the one who built an altar in God's name, then how much more should God reveal God's Self to Abraham, who circumcised himself for God's sake. And thus, "the Lord appear to him."[112]

Bar Kappara taught that every dream has its interpretation. Thus Bar Kappara taught that the "ladder" in Jacob's dream of Genesis 28:12 symbolizes the stairway leading up to the altar in the Temple in Jerusalem. "Set upon the earth" implies the altar, as Exodus 20:21 says, "An altar of earth you shall make for Me." "And the top of it reached to heaven" implies the sacrifices, the odor of which ascended to heaven. "The angels of God" symbolize the High Priests. "Ascending and descending on it" describes the priests ascending and descending the stairway of the altar. And the words "and, behold, the Lord stood beside him" in Genesis 28:13 once again invoke the altar, as in Amos 9:1, the prophet reports, "I saw the Lord standing beside the altar."[58]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[113]

Exodus chapter 18

Interpreting Exodus 18:21 together with Deuteronomy 1:13, Maimonides taught that judges must be on the highest level of righteousness. An effort should be made that they be white-haired, of impressive height, of dignified appearance, and people who understand whispered matters and who understand many different languages so that the court will not need to hear testimony from an interpreter.[114] Maimonides taught that one need not demand that a judge for a court of three possess all these qualities, but a judge must, however, possess seven attributes: wisdom, humility, fear of God, loathing for money, love for truth, being beloved by people at large, and a good reputation. Maimonides cited Deuteronomy 1:13, "Men of wisdom and understanding," for the requirement of wisdom. Deuteronomy 1:13 continues, "Beloved by your tribes," which Maimonides read to refer to those who are appreciated by people at large. Maimonides taught that what will make them beloved by people is conducting themselves with a favorable eye and a humble spirit, being good company, and speaking and conducting their business with people gently. Maimonides read Exodus 18:21, "men of power," to refer to people who are mighty in their observance of the commandments, who are very demanding of themselves, and who overcome their evil inclination until they possess no unfavorable qualities, no trace of an unpleasant reputation, even during their early adulthood, they were spoken of highly. Maimonides read Exodus 18:21, "men of power," also to imply that they should have a courageous heart to save the oppressed from the oppressor, as Exodus 2:17 reports, "And Moses arose and delivered them." Maimonides taught that just as Moses was humble, so, too, every judge should be humble. Exodus 18:21 continues "God-fearing," which is clear. Exodus 18:21 mentions "men who hate profit," which Maimonides took to refer to people who do not become overly concerned even about their own money; they do not pursue the accumulation of money, for anyone who is overly concerned about wealth will ultimately be overcome by want. Exodus 18:21 continues "men of truth," which Maimonides took to refer to people who pursue justice because of their own inclination; they love truth, hate crime, and flee from all forms of crookedness.[115]

Exodus chapter 19

Baḥya ibn Paquda posited that that people's obligation to render service is proportionate to the degree of benefit that they receive. In every period, events single out one people from all others for special benefits from God. That people then has a special obligation to render additional service to God beyond that required of other peoples. There is no way of determining by the intellect alone what that service should be. Thus, God chose the Israelites from among other nations by bringing them out of Egypt, dividing the Sea, and bestowing other benefits. Correspondingly, God singled out the Jews for service so that they can express their gratitude to God; and, in return for their acceptance of this service, God has assured them a reward in this world and in the next. All this, Baḥya argued, can only be clearly made known by the Torah, as Exodus 19:4–6 says, "You have seen what I did unto the Egyptians and how I bore you on eagles' wings, and brought you unto Myself. Now, therefore, if you will obey My voice indeed, and keep My covenant, then you shall be a treasure to Me above all people and you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation."[116]

Exodus chapter 20

Baḥya ibn Paquda argued that because the wholehearted acceptance of the unity of God is the root and foundation of Judaism, God's first words to the Israelites at Mount Sinai in Exodus 20:2–3 and Deuteronomy 5:6–7 were: "I am the Lord your God . . . you shall not have other gods before Me," and then God exhorted the Israelites through Moses, saying in Deuteronomy 6:4: "Hear O Israel the Lord, is our God, the Lord is One."[117]

Interpreting the prohibition of coveting in Exodus 20:14 and desiring in Deuteronomy 5:18, Maimonides taught that any person who covets a servant, a maidservant, a house, or utensils that belong to a colleague, or any other article that the person can purchase from the colleague and pressures the colleague with friends and requests until the colleague agrees to sell, violates a negative commandment, even though the person pays much money for it, as Exodus 20:14 says, "Do not covet." Maimonides taught that the violation of this commandment was not punished by lashes, because it does not involve a deed. Maimonides taught that a person does not violate Exodus 20:14 until the person actually takes the article that the person covets, as reflected by Deuteronomy 7:25: "Do not covet the gold and silver on these statues and take it for yourself." Maimonides read the word for "covet" in both Exodus 20:14 and Deuteronomy 7:25 to refer to coveting accompanied by a deed. Maimonides taught that a person who desires a home, a spouse, utensil, or anything else belonging to a colleague that the person can acquire violates a negative commandment when the person thinks in the person's heart how it might be possible to acquire this thing from the colleague. Maimonides read Deuteronomy 5:18, "Do not desire," to refer even to feelings in the heart alone. Thus, a person who desires another person's property violates one negative commandment. A person who purchases an object the person desires after pressuring the owners and repeatedly asking them, violates two negative commandments. For that reason, Maimonides concluded, the Torah prohibits both desiring in Deuteronomy 5:18 and coveting in Exodus 20:14. And if the person takes the article by robbery, the person violates three negative commandments.[118]

Baḥya ibn Paquda read the words "You shall not murder" in Exodus 20:13 to prohibit suicide, as well as murdering any other human being. Baḥya reasoned that the closer the murdered is to the murderer, the more the punishment should be severe, and thus the punishment for those who kill themselves will undoubtedly be very great. Baḥya taught that for that reason, people should not recklessly endanger their lives.[119]

Isaac Abravanel noted that the order of Exodus 20:14, "You shall not covet your neighbor's house; you shall not covet your neighbor's wife," differs from that in Deuteronomy 5:18, "Neither shall you covet thy neighbor's wife; neither shall you desire your neighbor's house." Abravanel deduced that Exodus 20:14 mentions the things that might be coveted in the order that a person has need of them, and what it behooves a person to try to acquire in this world. Therefore, the first coveted item mentioned is a person's house, then the person's spouse, then the person's servants, and lastly the person's animals that do not speak. Deuteronomy 5:18, however, mentions them in the order of the gravity of the sin and evil. The evilest coveting is that of another person's spouse, as in David's coveting of Bathsheba. Next in magnitude of evil comes coveting the house in which one's neighbor lives, lest the person evict the neighbor and take the neighbor's home. Next comes the neighbor's field, for although a person does not live there as in the house, it is the source of the neighbor's livelihood and inheritance, as in the affair of Ahab and the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite. After the field Deuteronomy 5:18 mentions servants, who Abravanel valued of lesser importance than one's field. Next come the neighbor's animals, who do not have the faculty of speech, and lastly, to include the neighbor's inanimate moveable property, Deuteronomy 5:18 says "and anything that is your neighbor's."[120][121]

Maimonides taught that God told the Israelites to erect the altar to God's name in Exodus 20:21 and instituted the practice of sacrifices generally as transitional steps to wean the Israelites off of the worship of the times and move them toward prayer as the primary means of worship. Maimonides noted that in nature, God created animals that develop gradually. For example, when a mammal is born, it is extremely tender, and cannot eat dry food, so God provided breasts that yield milk to feed the young animal, until it can eat dry food. Similarly, Maimonides taught, God instituted many laws as temporary measures, as it would have been impossible for the Israelites suddenly to discontinue everything to which they had become accustomed. So God sent Moses to make the Israelites (in the words of Exodus 19:6) "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." But the general custom of worship in those days was sacrificing animals in temples that contained idols. So God did not command the Israelites to give up those manners of service, but allowed them to continue. God transferred to God's service what had formerly served as a worship of idols, and commanded the Israelites to serve God in the same manner—namely, to build to a Sanctuary (Exodus 25:8), to erect the altar to God's name (Exodus 20:21, to offer sacrifices to God (Leviticus 1:2), to bow down to God, and to burn incense before God. God forbad doing any of these things to any other being and selected priests for the service in the temple in Exodus 28:41. By this Divine plan, God blotted out the traces of idolatry, and established the great principle of the Existence and Unity of God. But the sacrificial service, Maimonides taught, was not the primary object of God's commandments about sacrifice; rather, supplications, prayers, and similar kinds of worship are nearer to the primary object. Thus God limited sacrifice to only one temple (see Deuteronomy 12:26) and the priesthood to only the members of a particular family. These restrictions, Maimonides taught, served to limit sacrificial worship, and kept it within such bounds that God did not feel it necessary to abolish sacrificial service altogether. But in the Divine plan, prayer and supplication can be offered everywhere and by every person, as can be the wearing of tzitzit (Numbers 15:38) and tefillin (Exodus 13:9, 16) and similar kinds of service.[122]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Exodus chapter 18

The 1639 Fundamental Agreement of the New Haven Colony reported that John Davenport, a Puritan clergyman and co-founder of the colony, declared to all the free planters forming the colony that Exodus 18:2, Deuteronomy 1:13, and Deuteronomy 17:15 described the kind of people who might best be trusted with matters of government, and the people at the meeting assented without opposition.[123]

Gunther Plaut observed that in Deuteronomy 1:13, the people—not Moses, as recorded in Exodus 18:21 and 24–25—chose the officials who would share the tasks of leadership and dispute resolution.[124] Jeffrey Tigay, however, reasoned that although Moses selected the appointees as recorded in Exodus 18:21 and 24–25, he could not have acted without recommendations by the people, for the officers would have numbered in the thousands (according to the Talmud, 78,600), and Moses could not have known that many qualified people, especially as he had not lived among the Israelites before the Exodus.[125] Robert Alter noted several differences between the accounts in Deuteronomy 1 and Exodus 18, all of which he argued reflected the distinctive aims of Deuteronomy. Jethro conceives the scheme in Exodus 18, but is not mentioned in Deuteronomy 1, and instead, the plan is entirely Moses's idea, as Deuteronomy is the book of Moses. In Deuteronomy 1, Moses entrusts the choice of magistrates to the people, whereas in Exodus 18, he implements Jethro's directive by choosing the judges himself. In Exodus 18, the qualities to be sought in the judges are moral probity and piety, whereas Deuteronomy 1 stresses intellectual discernment.[126]

Exodus chapter 19

Noting that Jewish tradition has not preserved a tradition about Mount Sinai's location, Plaut observed that had the Israelites known the location in later centuries, Jerusalem and its Temple could never have become the center of Jewish life, for Jerusalem and the Temple would have been inferior in holiness to the God's mountain. Plaut concluded that Sinai thus became in Judaism, either by design or happenstance, a concept rather than a place.[127]

Harold Fisch argued that the revelation at Mount Sinai beginning at Exodus 19 is echoed in Prince Hamlet's meeting with his dead father's ghost in Hamlet 1.5 of William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. Fisch noted that in both cases, a father appears to issue a command, only one is called to hear the command, others stay at a distance in terror, the commandment is recorded, and the parties enter into a covenant.[128]

Alter translated Numbers 15:38 to call for "an indigo twist" on the Israelites' garments. Alter explained that the dye was not derived from a plant, as is indigo, but from a substance secreted by the murex, harvested off the coast of Phoenicia. The extraction and preparation of this dye were labor-intensive and thus quite costly. It was used for royal garments in many places in the Mediterranean region, and in Israel it was also used for priestly garments and for the cloth furnishings of the Tabernacle. Alter argued that the indigo twist indicated the idea that Israel should become (in the words of Exodus 19:6) a "kingdom of priests and a holy nation" and perhaps also that, as the covenanted people, metaphorically God's firstborn, the nation as a whole had royal status.[129]

Maxine Grossman noted that in Exodus 19:9–11, God told Moses, "Go to the people and consecrate them today and tomorrow. Have them wash their clothes and prepare for the third day," but then in Exodus 19:14–15, Moses told the people, "Prepare for the third day; do not go near a woman." Did God evince a different conception of "the people" (including women) than Moses (apparently speaking only to men)? Or does Moses's statement reveal a cultural bias of the Biblical author?[130]

Moshe Greenberg wrote that one may see the entire Exodus story as "the movement of the fiery manifestation of the divine presence."[131] Similarly, William Propp identified fire (אֵשׁ, esh) as the medium in which God appears on the terrestrial plane—in the Burning Bush of Exodus 3:2, the cloud pillar of Exodus 13:21–22 and 14:24, atop Mount Sinai in Exodus 19:18 and 24:17, and upon the Tabernacle in Exodus 40:38.[132]

Everett Fox noted that "glory" (כְּבוֹד, kevod) and "stubbornness" (כָּבֵד לֵב, kaved lev) are leading words throughout the book of Exodus that give it a sense of unity.[133] Similarly, Propp identified the root kvd—connoting heaviness, glory, wealth, and firmness—as a recurring theme in Exodus: Moses suffered from a heavy mouth in Exodus 4:10 and heavy arms in Exodus 17:12; Pharaoh had firmness of heart in Exodus 7:14; 8:11, 28; 9:7, 34; and 10:1; Pharaoh made Israel's labor heavy in Exodus 5:9; God in response sent heavy plagues in Exodus 8:20; 9:3, 18, 24; and 10:14, so that God might be glorified over Pharaoh in Exodus 14:4, 17, and 18; and the book culminates with the descent of God's fiery Glory, described as a "heavy cloud," first upon Sinai and later upon the Tabernacle in Exodus 19:16; 24:16–17; 29:43; 33:18, 22; and 40:34–38.[132]

Exodus chapter 20

Although Jewish tradition came to consider the words "I am the Lord your God" in Exodus 20:1 the first of the Ten Commandments, many modern scholars saw not a command, but merely a proclamation announcing the Speaker.[134]

In 1980, in the case of Stone v. Graham, the Supreme Court of the United States held unconstitutional a Kentucky statute that required posting the Ten Commandments on the wall of each public classroom in the state. The Court noted that some of the Commandments apply to arguably secular matters, such those at Exodus 20:11–16 and Deuteronomy 5:15–20, on honoring one's parents, murder, adultery, stealing, false witness, and covetousness. But the Court also observed that the first part of the Commandments, in Exodus 20:1–10 and Deuteronomy 5:6–14 concerns the religious duties of believers: worshipping the Lord God alone, avoiding idolatry, not using the Lord's name in vain, and observing the Sabbath Day. Thus the Court concluded that the pre-eminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls was plainly religious.[135]

Shubert Spero asked why the Ten Commandments do not mention sacrifices, Passover, or circumcision. Joseph Telushkin answered that the Ten Commandments testify that moral rules about relations between people are primary, and thus, “Morality is the essence of Judaism.”[136]

In 1950, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism ruled: "Refraining from the use of a motor vehicle is an important aid in the maintenance of the Sabbath spirit of repose. Such restraint aids, moreover, in keeping the members of the family together on the Sabbath. However where a family resides beyond reasonable walking distance from the synagogue, the use of a motor vehicle for the purpose of synagogue attendance shall in no wise be construed as a violation of the Sabbath but, on the contrary, such attendance shall be deemed an expression of loyalty to our faith. . . . [I]n the spirit of a living and developing Halachah responsive to the changing needs of our people, we declare it to be permitted to use electric lights on the Sabbath for the purpose of enhancing the enjoyment of the Sabbath, or reducing personal discomfort in the performance of a mitzvah."[137]

Commandments

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 3 positive and 14 negative commandments in the parashah:[138]

- To know there is a God[20]

- Not to believe in divinity besides God[139]

- Not to make an idol for yourself[140]

- Not to worship idols in the manner they are worshiped[141]

- Not to worship idols in the four ways we worship God[141]

- Not to take God's Name in vain.[22]

- To sanctify the Sabbath with Kiddush and Havdalah[142]

- Not to do prohibited labor on the Sabbath[143]

- To respect your father and mother[24]

- Not to murder[25]

- Not to commit adultery[25]

- Not to kidnap[25]

- Not to testify falsely[25]

- Not to covet another's possession[26]

- Not to make human forms even for decorative purposes[144]

- Not to build the altar with hewn stones[29]

- Not to climb steps to the altar.[30]

In the liturgy

The second blessing before the Shema speaks of how God "loves His people Israel," reflecting the statement of Exodus 19:5 that Israel is God's people.[145]

The fire surrounding God's Presence in Exodus 19:16–28 is reflected in Psalm 97:3, which is in turn one of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service.[146]

Reuven Hammer noted that Mishnah Tamid 5:1[147] recorded what was in effect the first siddur, as a part of which priests daily recited the Ten Commandments.[148]

It is customary for listeners to stand while the reader chants the Ten Commandments in the synagogue, as if the listeners were themselves receiving the revelation at Sinai.[149]

The Lekhah Dodi liturgical poem of the Kabbalat Shabbat service quotes both the commandment of Exodus 20:8 to "remember" the Sabbath and the commandment of Deuteronomy 5:12 to "keep" or "observe" the Sabbath, saying that they "were uttered as one by our Creator."[150]

And following the Kabbalat Shabbat service and prior to the Friday evening (Ma'ariv) service, Jews traditionally read rabbinic sources on the observance of the Sabbath, including Genesis Rabbah 11:9.[151] Genesis Rabbah 11:9, in turn, interpreted the commandment of Exodus 20:8 to "remember" the Sabbath.[152]

The Kiddusha Rabba blessing for the Sabbath day meal quotes Exodus 20:8–11 immediately before the blessing on wine.[153]

Among the zemirot or songs of praise for the Sabbath day meal, the song Baruch Kel Elyon, written by Rabbi Baruch ben Samuel, quotes Exodus 20:8 and in concluding paraphrases Exodus 20:10, saying "In all your dwellings, do not do work—your sons and daughters, the servant and the maidservant."[154]

Similarly, among the zemirot for the Sabbath day meal, the song Yom Zeh Mechubad paraphrases Exodus 20:9–11, saying, "This day is honored from among all days, for on it rested the One Who fashioned the universe. Six days you may do your work, but the Seventh Day belongs to your God. The Sabbath: Do not do on it any work, for everything God completed in six days."[155]

Many Jews study successive chapters of Pirkei Avot (Chapters of the Fathers) on Sabbaths between Passover and Rosh Hashanah. And Avot 3:6 quotes Exodus 20:21 for the proposition that even when only a single person sits occupied with Torah, the Shechinah is with the student.[156]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For Parashah Yitro, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Hoseni, the maqam that expresses beauty, which is especially appropriate in this parashah because it is the parashah where the Israelites receive the Ten Commandments.[157]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is Isaiah 6:1–7:6 and 9:5–6.

Connection to the Parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah recount God's revelation. Both the parashah and the haftarah describe Divine Beings as winged.[158] Both the parashah and the haftarah report God's presence accompanied by shaking and smoke.[159] And both the parashah and the haftarah speak of making Israel a holy community.[160]

See also

Notes

- "Torah Stats for Shemoth". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- "Parashat Yitro". Hebcal. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008), pages 120–44.

- Exodus 18:1–5.

- Exodus 18:9–12.

- Exodus 18:13.

- Exodus 18:14–23.