Yoo Youngkuk

Yoo Youngkuk (劉永國; denoted as YYK)[1] is a pioneer of modern art of Korea and her first abstract painter. Yoo Younkuk and Kim Whanki (金煥基) are regarded as two grand masters of Korean abstract painting.

Yoo Youngkuk | |

|---|---|

Yoo Youngkuk, around 1979 | |

| Born | April 7, 1916 |

| Died | November 11, 2002 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | Republic of Korea |

| Movement | N.B.G. (Neo Beaux-arts Group), Free Artists’ Association, New Realism Group, Modern Art Society, Sin-Sang Hoe |

| Spouse | Kim Kisoon |

| Website | yooyoungkuk |

Born in a well-to-do family in Uljin, YYK graduated from the oil painting department of the Bunka Gakuin University (文化學院) in Tokyo (1938), where he encountered abstract painting from the west and decided to be an abstract painter. Interacting closely with Murai Masanari[2] and Hasegawa Saburo[3], pioneers of Japanese abstract painting, YYK participated actively in avant-garde movements in Japan and became a fellow of the Association of Free Artists (自由美術家協會, AFA).

After eight years of stay in Tokyo, YYK returned to Korea in 1943. Years later (1948), he founded the “Sinsasil-pa (新寫實派, New Realism Group)” with Kim Whanki and Lee Kyusang (李揆祥), the first avant-garde group in Korea, and taught at the Seoul National University as a professor for two years. However, it was not possible for YYK to engage in painting for more than a decade due to social turbulences during the Pacific and Korean wars.

When he resumed his painting career after the war, modern art in Korea was in her embryonic stage and YYK played major roles in setting overall direction as well as contextualizing and fixating modern art in Korea by organizing various groups and participating in exhibitions. Mountain was a favorite motif of his paintings, and he became known as “the painter of mountains”.

After the Sao Paulo biennial in 1963, YYK withdrew from group activities and focused on solo exhibitions which were held every other year for two decades. The painting style was changed from color fields to geometric forms and so on, and the style uniquely attributed to him nowadays was created in this period. The first solo exhibition held in 1964 firmly established him as the leading abstract painter and the 8th exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in 1979 was the summing-up of his career featuring major works made throughout his life.

From the sixties on, YYK suffered from numerous illnesses and was confined to activities in a wheelchair, but he continued to paint until 3 years before his death at the age of eighty-six. A survey of twenty art critics on the artistry of leading artists by Monthly Art (月刊美術) magazine[4] evaluated YYK as the most outstanding among over a hundred artists in Korea.

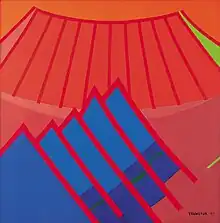

Strong lines and colorful planes forming geometrical shapes are a symbol of YYK’s paintings where vibrant colors, metaphysical patterns, and well-planned structural compositions are integrated to illuminate the sublimity and solemnity of nature.

Early life

YYK was born in 1916, six years after the annexation of Korea by the Japanese Empire, in Uljin, a city on the east coast located at the end of Taebaek mountains in Gangwon province, as the third son (sixth of eight children) between Yoo Moonjong (1876–1946) and Hwang Dongho (1880–1963). Yoo Moonjong was a land proprietor in Uljin who engaged mainly in agriculture, as well as fishery and brewery businesses. Yoo Moonjong provided substantial military rations to General Shin Dol-seok at the end of the Korean Empire (1906) and founded Jedong Elementary School (1922).

After graduating Uljin elementary school, YYK left home at the age of thirteen, in order to study at Chei Kobo (第2高普, No. 2 High School at Gyeongseong, currently Kyungbok Middle and High School) in Seoul. The subject YYK liked most at school was mathematics and he did not show particular interest in fine art classes or participated in extracurricular activities on art. However, Sato Kunio[5], a Japanese art teacher, earned the respect of Korean students due to his open-minded and liberal personality and influenced many students to become artists. It was not a coincidence that Chei Kobo graduated many masters of Korean modern art who learned from Sato Kunio during this period.

In colonial days, students were required to speak only Japanese at school, keenly watched by Japanese teachers and often beaten for misdemeanors. One day in his graduation year, YYK was beaten by his teacher over refusing to spy on fellow students. Being already disenchanted with the repressive atmosphere of the school, YYK quit the school days after and went to Japan for further study with the support of his father. Becoming a captain of a cargo ship and traveling the world freely was the future goal when YYK went to Japan. However, he had to change his plan because the merchant marine academy at Yokohama, which YYK wished to enter, required a high school diploma for an application. Instead, YYK decided to enter the oil painting department of the Bunka Gakuin University in Tokyo, an art school known for its liberal campus atmosphere and policies.

Tokyo Period (1935–1943)

Bunka Gakuin

It was at Bunka Gakuin that YYK first encountered western art and learned about works of old masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt, and others from artbooks at the school. Amazed at the exquisiteness of their work, YYK thought that there was nothing more for him to add to the traditional field, and decided to pursue something completely different, abstract painting from the start. There was no professor who majored in abstract painting at Bunka Gakuin at the time.

The avant-garde movement in Japan already started in the 1920s, and by the time YYK arrived at Tokyo (1935) Russian futurism and constructivism were widely permeated to Japanese art scenes. Hasegawa Saburo and Murai Masanari, who had been to Paris, were leading Japanese avant-garde movements, and also organizers of the Association of Free Artists (AFA). Murai Masanari was ten years senior to YYK at Bunka Gakuin University and became a close associate of him. YYK had lifelong respect toward Murai Masanari as a college senior and fellow artist.

_mixed_media_65x90cm.jpg.webp)

YYK made his debut as an artist at the 7th exhibition of the Independent Artists Association (獨立美術家協會) in 1937 and actively participated in Jiyu-ten (自由展, exhibition of Association of Free Artists) which was organized by AFA. YYK won the prize of the society at the second exhibition (1938) and became a fellow. The experience of participating actively in the mainstream of the Japanese avant-garde movement provided YYK with a solid basis for his future activities in Korea. Unfortunately, YYK’s works made in Tokyo days were all lost during the Korean War except for some relief works. For the 8th solo exhibition in 1979, YYK reproduced reliefs from remaining postcards with the help of Yoo Lizzy[6], his daughter and a metalcraft artist. The originals were produced in the late 1930s, not much later than Piet Mondrian and Jean Arp, leaders of Abstraction-Création group in Paris, showing that YYK was keenly aware of French avant-garde movements and tried to join the most cutting-edge trends.[7]

Photography

During the World War II in Japan artists were forced to work on documentary war paintings and Hasegawa Saburo, a close associate of YYK, unwilling to comply with the policy, chose to work on photography instead. YYK completed the photography class at the Oriental Photography School in Tokyo(1940), and exhibited photo works at the 6th exhibition of Association of Art Creators (formerly AFA) which portrayed mostly historical remains of Gyeongju; old capital of Silla dynasty. Photography was life-long hobby of YYK. YYK later mentioned that he learned photography because he thought photographers had better chances of finding jobs than artists during the wartime.[8]

The Blank Period (1943–1955)

YYK came back to Korea in the middle of the Pacific war, and several years later the Korean war broke out. Longer than a decade YYK had to work just to survive and support his family of six. YYK married Kim Kisoon of Seoul by an arranged marriage one year after his return and the couple had two daughters and two sons.

Before the Korean War (1943~1950)

As the Pacific war became fiercer, it became difficult for YYK to stay in Tokyo longer and he came back to Uljin (1943). There being no proper job for him and not wanting to depend on his father, YYK engaged in the fishing business for five years at Jukbyeon–a fishing port near Uljin using a fishing boat owned by his father. The boat carried about ten fishermen on it, and YYK often went fishing with them all around the East Sea (Sea of Japan) for months. He was quite skillful in gathering information and tracing the right fishing grounds and his boat used to make the largest catch around the area. The experience of working at sea and observing the wild nature closely affected the spirit of the artist, and sceneries of sunrise and sunset, interplay of sunlight with the sea, and mountains seen from the ocean became favorite motifs of his work throughout life.

When Kim Whanki, a close associate of YYK since his Tokyo days and an assistant professor at the College of Fine Arts of the Seoul National University (SNU) at the time, asked YYK to join the university as a full-time lecturer (1948), he went up to Seoul. That year, YYK formed Sinsasil-pa with Kim Whanki and Lee Kyusang and held the 1st exhibition in Seoul.[9] Even though small in number, all members were experienced in avant-garde movements in Japan and their manifesto of fine art based on the concept of pure forms, for the first time in Korea, left lasting impacts on the modern art movement of Korea.[10]

Korean War

During the three months when Seoul was occupied by North Korean Army (June 28~Sep. 28, 1950) and the following several months after restoration of the city, YYK and his family had to suffer extreme hardships. On the brink of the second occupation of Seoul (January 1951) they took refuge to Uljin, but economic situation was no better. Standing at the frontline of living, YYK took over a brewery factory of his father at Jukbyeon that was abandoned and not operating for years. After a repair, he resumed liquor production and worked as a laborer as well as an entrepreneur. To his luck, demands for liquors soared up as many refugees from North Korea flocked into the area, and by hard work and business skill YYK became the most prosperous man in town within few years. The business was going well, but YYK quit the business to paint again and moved up to Seoul. YYK was 39 years old and had been out of painting for twelve years when he decided to resume his career. Later he lamented the period as "a lost decade". However, continuing income from the brewery business, which he left to others to manage, supported YYK for the next two decades when abstract paintings made no money, and let him concentrate on painting full time. All the works of YYK made before the Korean War were destroyed during the war except two and works shown at the 3rd exhibition of Sinsasil-pa were later found in bad shape and subsequently restored.

Pursuit of Abstract Art (1955–1999)

YYK’s activities after the Korean War could be divided into three periods. In the first period, YYK tried to contextualize and fixate on modern art in Korea through group exhibitions. He was recognized as the pioneer of Korean modern art and called the painter of mountains. In the second, YYK withdrew from group activities and held solo exhibitions every other year for two decades. Leading a strenuous life with a high regimen, YYK accomplished the painting style uniquely attributed to him nowadays. The first solo exhibition in 1964 firmly established YYK as the leading abstract painter of Korea and earned him a new reputation, the magician of colors.[11] The 8th exhibition at MMCA at Deoksugung palace in 1979 was the culminating moment of his career. The last period was tinged with frequent illnesses, yet YYK continued to paint endowing characteristic lyricism to his work until three years to death.

1955–1963: group exhibition period

_at_the_opening_ceremony_of_the_4th_Contemporary_Artists_exhibition_hosted_by_Chosun_Ilbo_with_chairman_Bang_Il_Young_(front_left)_(April_1960).jpg.webp)

When YYK decided to paint again, two years after the war, Korea was one of the most isolated countries in the world, and neither information on the world trends nor basic materials necessary to paint were available. It was only in the 1960s that information on outside art trends became known to Korea through art magazines imported from Japan.

Back in Seoul, YYK established Modern Art Association (MAA) with fellow artists[12], which initiated the era of group exhibitions in Korea (1956). He also played leading roles in Contemporary Artist exhibitions (1958-61)[13] organized by The Chosun Ilbo (daily newspaper).

Largest dispute in fine art societies of Korea through late 50’s to 60’s was reformation of the National Art Exhibition (NAE) which was an annual event presided by the government. It was a gateway to selecting talented artists, but often criticized for cronyism in selection process and backwardness of management. YYK was an advocate of reformation of NAE and participated in 1960 Contemporary Artist Association[14] acting as its representative. Furthering the issue, he established ShinSang-Hoe (New Form Group, 新象會)[15] with the goal of discovering and promoting young artists through fair selection processes (1962). All those activities showed that YYK played a major role in establishing modern art in Korea.

The works made in this period showed several characteristics; complicated yet diverse dimensional composition, thick and strong outlines making rigid but geometrical forms, and heavily painted primary colors delivering thick and rough texture.[16] Even though abstract in form, semblances to the landscapes of Uljin and Jukbyeon could be traced in his work. From this time on, the mountain was taken as a continuing motif of his work, and a behind motive was that YYK thought he could work on it for a long time without frequent changes or getting tired of it.

1964–1983: solo exhibition period

After the Korean war, several Korean modern artists[17], frustrated with situations at home, went to Paris to advance their art and YYK thought about it too. However, the the possibility was ruled out soon because he lacked proficiency in English or French that he regarded as essential to working in the mainstream and communicating with leading artists.

The 7th Sao Paulo biennial held in 1963 in Brazil was a turning point of YYK’s career in some ways. Kim Whanki led the Korean mission attending the exhibition and settled in New York afterwards. In a letter, Kim Whanki described New York artists as working almost mechanically at their studios from nine to six like salary men working at the company, in addition to other stories on New York. News about contemporary art in US was very stimulating to YYK and made him to think about his current circumstance. After some reflection, YYK confided that he could do the same in Korea, and that meant more than just willingness to keep the working hours because he had been already quite punctual with his schedules. The truth was that he had no other way.

YYK had a belief that an artist must watch the tide of times closely, analyze where it is heading, and prepare for the days when he reaches the peak of his career.[18] Observations on the works of leading artists and communication with them are very helpful in the process, but virtually isolated from the mainstream, YYK had to find his own way relying on self-study and self-introspection. What YYK had in mind at the time can be guessed from a debate YYK had with fellow artists about the promotion of Korean modern art to the world. Against the argument that taking motifs from traditional culture makes Korean art, a late starter in modern art, competitive against the west from where modern art originated, YYK emphasized that genuinely Korean art is made by creating art that truly excels and cannot be made elsewhere. Creating art that is unique and ahead of time yet possesses excelling aesthetic universals was the ultimate goal of YYK.

From that perspective, the mountain was a good motif for painting because it is beautiful, changing all the time, and never runs out of content. Furthermore, the mountain is loved universally by almost everybody, everywhere. Observing and analyzing the motif in his own way, YYK carried out studies on abstract painting by delving into various painting styles like a researcher carrying out experiments.

Dedicating most of his time and energy to group activities and to a guiding role over general direction of Korean art, YYK did not hold solo exhibitions until he was forty-nine years old, much later than his colleagues. Realizing that it was the time to pursue his own art world without involvement in group work and other duties, YYK withdrew from all group exhibitions and other activities and focused solely on solo exhibitions.

Like a man trying to compensate for the lost decade, YYK worked almost defiantly, nine to ten hours a day, six days a week, and maintained the work habit for two decades until damaged hip joint from extensive work in the standing posture and deteriorating health prevented him from doing so and virtually confined him to work on a wheelchair in the 1980s.

YYK was a department chair at the oil painting department of Hongik University, a renowned art school in Korea, for several years in the 1960s, but resigned from the university to put more time into his work. He even declined visitors to his home so as not to be disturbed. Eleven solo exhibitions were held almost biannually during the next twenty years, and that was the most strenuous part of YYK’s career as well as the time when the painting style uniquely attributed to YYK was created.

Five days trips to Jukbyeon once every five weeks to supervise the brewery firm, traveling through the mountains of Gangwon province and along the coastline of the East Sea was a routine of YYK that was continued until he sold the brewery in the middle of 1970s. Regular travels gave him a sense of liberation from strenuous life in Seoul and artistic inspirations too. Hours of walking along Jukbyeon beach, passing around the lighthouse, and visiting local fish market were relaxing moments.

The first solo exhibition of 1964

The first exhibition was the most monumental and landmark success that was widely praised for excelling in aesthetics and sincerity of the theme. The sharp contrast of colors and density of composition were the main characteristics of the paintings presented at the exhibition. Thick and strong lines of the previous era were gone, and vivid color phases filled the canvas. Keen strokes resembling outbreaks of the Earth's crust brought dynamics to the canvas (see the painting shown here).[19] Kim Byungki, an art critic and artist, wrote that "the energy bursting out from the painting, like lava exploding from a crate, delivers inexplicable emotions to the viewers.[20]” Lee Il, a critic, commented that “balance and harmony of colors in the paintings shows that YYK's mastery of color reached a supreme level.[21]” Another critic Kim Youngjoo noted that the works of YYK carried the essence of the era.[22] Compared to former works portraying nature with strict composition, works of this period deliver tensions with dynamic senses of motion freed from rules that YYK explored in the previous time.

Geometric abstraction (1968–1973)

In his 50s, YYK started to explore geometrical forms and primary colors. The thick and rough texture of the paints of the previous era disappeared and over all the calmness and stability were brought to the canvases.[23] Primary and complementary colors were used to escalate the visual sensation, and lines intersecting the spaces diagonally, vertically, and horizontally imparted a sense of dynamism to the canvas where essential figurative elements of natural objects were extracted in their simplest forms and repeatedly duplicated to provide depth and perspective to the painting. Shades of the sunlight and spatial composition drawn as straight lines or main figures appearing as negative exposition inside the primary color field were typical characteristics of YYK's work of this period.

Pastoral color fields (1973–1979)

In 1977, YYK sold the house at Yaksu-dong where he lived for thirty years and moved to Deungchon-dong at the outskirts of Seoul. The newly built house[24][i] was very quiet and surrounded by a little hill at the back with many trees, and he could watch pheasants resting in backyards through the windows of his atelier. Works of this period were painted in gentler colors using softer lines providing intimacy and comfort rather than tension and rigor. Trees were often depicted in ‘Y’ shapes and mountains had softer and rounder angles.[25]

Peace and comfort (1978–1999)

In his later years, YYK was often hospitalized for months due to many kinds of illnesses; myocardial infarction (1976), thighbone fracture (1979), heart surgery (1983), hip joint surgery (1984), several strokes and so on. Even though deteriorating health severely limited his activities, YYK remained sharp to the end. Almost defiantly, YYK refused to rest and said in an interview, "Now that I am getting old, I need more enthusiasms and stimuli to continue. When I stare at my paintings, I feel a sense of tension, which fills me with ardor and enthusiasm. I will train myself and paint with this kind of passion to the end.[26]" Works made in his seventies, painted in pure colors and figures, impart a sense of tenderness and comfort. Basic patterns such as circles, triangles, and rectangles depicting sky, mountain, Sun, and trees deliver joy and delight. In comparison, works made in his eighties reflect the solemn moments of a man confronting his ultimate destiny in peacefulness and serenity.

A survey of 20 art critics on leading artists by the Monthly Art magazine (October issue) in 1990 evaluated YYK’s artistry as the most outstanding among 136 leading Korean fine artists including 61 western style painters, 42 Korean traditional painters, and 33 sculptors.

Death

Even though YYK suffered much from health problems since his sixties, works of this period did not show any signs of anxiety, which is in conformity with his nature. Even in many emergency situations, he was always calm. Kim Kisoon, his wife, recalled that YYK lived a life of his own and pursued his own way of living without clinging to longevity or reputation. He used to say, "I became a painter to live free without being interfered by others. Why should I worry now?[27]" YYK died on November 11, 2002, and the epitaph inscribed on his tombstone states; "The mountain is not in front of me but inside of me.", which was quoted over from his statement.

When he passed away in 2002, his lifelong perseverance and tenacity in the pursuit of abstract painting and puritan work ethic as a professional painter were widely praised in public[28] and his funeral was attended by three thousand people. Posthumously MMCA held the centennial exhibition in his honor in 2016 with a title of Absoluteness and Freedom at the Deoksugung palace in Seoul, which was a third of its kind after Lee Jung-seob and Varlen Pen.[29] The exhibition at Kukje gallery in 2022 with the title of Colors of Yoo Youngkuk was attended by sixty thousand people, drawing wide attention from the public.

Epilogue

YYK was a true pioneer in abstract painting and modern art in general who persevered a long and lonely journey of creating a unique art world with excelling beauty at the most difficult times of modern history.

Having not expected abstract paintings ever to become a source of income in his lifetime, YYK was nonchalant about the needs of the local art market. He used to say, "I will study painting up to sixty years old, and then paint whatever I want". In fact, his painting was first sold when he was sixty years old when the Korean economy started to prosper. Lee Byung-chul (李秉喆), founder of Samsung conglomerate, was the first purchaser.

References

Footnotes

- "Home". yooyoungkuk.org.

- http://www.muraimasanari.com/%7CMurai Masanari

- http://www.artnet.com/artists/saburo-hasegawa/past-auction-results%7CHasegawa Saburo

- "The Artistic Merit and Price of Artworks: An Analysis of 20 Art Critics' Responses". Monthly Art. October 1990.

- Inspired by their former teacher Sato Kunio, YYK and his five fellow alumni from Chei Kobo [i.e., Chang Ucchin, Kim Chang Euk (金昌億), Lim Wan Kyu (林完圭), Lee Daewon (李大源), and Kwon Okyeon (權玉淵)] established the 2-9 Group in 1961. The “2” refers to No. “2” High School at Gyeongseong, while the “9” (in Korean, “ku”) is a homonym with the first syllable of their teacher’s name.

- Yoo Lizzy (1945–2013). Former professor at Seoul National University College of Fine Arts, founder of Chiwoo Craft Museum, currently Yoo Lizzy Craft Museum. ("유리지공예관")

- Oh, Gwangsu. Yoo Youngkuk, the Pioneer of Korean Abstract Art. pp. 33–34.

- Oh, Gwangsu. Yoo Youngkuk, the Pioneer of Korean Abstract Art. pp. 43–44.

- The last exhibition of Sinsasil-pa was held at Busan during wartime.

- Lee, Inbum (2008). "Neo Realism Group - The First Pure Painterly Artist Group". Art Culture: 37.

- Oh, Gwangsu (2012). Yoo Youngkuk, the Pioneer of Korean Abstract Art - His Life an Prospect. Paju: Maronie Books. p. 222.

- To carry out independent activities as the avant-garde of a contemporary painting movement with Park KoSuk (朴古石), Lee Kyusang, Han Mook (韓墨), and Hwang Yeomsu (黃廉秀).

- After the fourth exhibition of the Modern Art Association (November 1958), YYK resigned from the MAA and focused his efforts on the Contemporary Artists exhibitions, which he believed represented a welcome alternative to the contemporary art movement. Notably, the Contemporary Artists exhibition had originally been established after some internal disputes within the MAA.

- The 1960 Contemporary Artists Association announced the nine articles of their manifesto, which include demands for the reform of the NAE and the construction of a contemporary art museum.

- Although the tenth NAE had demonstrated some reform, the eleventh exhibition had again shown signs of regression. Thus, YYK and his colleagues including Kang Roksa (姜鹿史), Kim JongHwi (金鍾輝), Kim Changeuk, Moon Woosik (文友植), Park Sukho (朴錫浩), Lee Daewon, Ree Bong Sang (李鳳商), Chung Mun Kyu (鄭文圭), Lim Wan Kyu, Cho ByungHyun (趙炳賢), Han BongDuk (韓奉德), and Hwang Kyubaik (黃圭伯), established ShinSang-Hoe.

- Park, Chun-nam (1996). Yoo Youngkuk Solo Exhibition Catalogue. Seoul: Hoam Art Gallery. p. 146.

- Nam Kwan, Rhee Seundja, Lee Ungno went to Paris and settled there. Kim Whanki also spent a few years in Paris.

- In a dialogue with his elder son Jin Yu.

- Oh, Gwangsu (2012). "Abstract Shape and Color Filed Composition: the Art World of Yoo Youngkuk". Yoo Youngkuk 10th Anniversary Exhibition Catalogue: 31.

- Oh, Gwangsu. "Abstract Shape and Color Filed Composition: the Art World of Yoo Youngkuk": 32.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Oh, Gwangsu. "Abstract Shape and Color Filed Composition: the Art World of Yoo Youngkuk": 32–33.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Oh, Gwangsu. "Abstract Shape and Color Filed Composition: the Art World of Yoo Youngkuk": 33.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Park, Chun-nam (1996). Yoo Youngkuk Solo Exhibition Catalogue. p. 144.

- Designed by YYK’s younger son Kun Yu, an architect. Later in 1987, YYK moved to a house in Bangbae-dong also designed by Kun Yu, where YYK spent the rest of his life.

- Park, Chun-nam. Yoo Youngkuk Solo Exhibition Catalogue. p. 151.

- Kim, Gwang-wu (December 1, 2003). "Absracting Landscape: The Formativeness in Yoo Youngkuk's work". The Professor's Times.

- Oh, Gwangsu (2012). Abstract Shape and Color Field Composition. p. 236.

- Oh, Gwangsu (November 12, 2002). "In Memory of the Late Yoo Youngkuk: An Uncompromising Artistic Spirit". The Dong-a Ilbo.

- "100th Anniversary of Korean Modern Master: YOO YOUNGKUK (1916-2002)". The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Sources

- “The Artistic Merit and Price of Artworks: An Analysis of 20 Art Critics’ Responses”. Monthly Art, October 1990.

- Kim, Gwang-wu, "Abstracting Landscape: The Formativeness in Yoo Youngkuk's work", The Professor's Times, December 1, 2003.

- Lee, Inbum, "Neo Realism Group – The First Pure Painterly Artist Group", (Art Culture, 2008).

- Oh, Gwangsu, "Abstract Shape and Color Field Composition: The Art World of Yoo Youngkuk", in Yoo Youngkuk 10th Anniversary Exhibition Catalogue, (Paju: Maronie Books, 2012).

- Oh, Gwangsu, Yoo Youngkuk, the pioneer of Korean Abstract Art – His Life and Prospect, (Paju: Maronie Books, 2012).

- Park, Chun-nam, Yoo Youngkuk Solo Exhibition Catalogue, (Hoam Art Gallery, 1996