Yury Dombrovsky

Yury Osipovich Dombrovsky (Russian: Ю́рий О́сипович Домбро́вский; 12 May [O.S. 29 April] 1909 – 29 May 1978) was a Russian writer who spent nearly eighteen years in Soviet prison camps and exile.

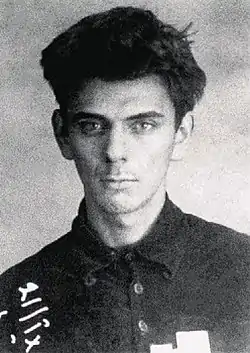

Yury Dombrovsky | |

|---|---|

Dombrovsky after arrest in 1932 | |

| Born | 12 May [O.S. 29 April] 1909 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 29 May 1978 (aged 69) Moscow, RSFSR, USSR |

| Occupation | Poet, literary critic, novelist, journalist, archeologist |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire (1909–1917) Soviet Russia (1917–1922) Soviet Union (1922–1978) |

| Notable works | The Faculty of Useless Knowledge |

Life and career

Dombrovsky was the son of Jewish lawyer Joseph Dombrovsky[1] and Russian mother.

Dombrovsky fell foul of the authorities as early as 1932, for his part in the student suicide case described in The Faculty of Useless Knowledge. He was exiled to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan where he established himself as a teacher, and which provided the setting for his novel The Keeper of Antiquities. This work, translated into English by Michael Glenny, gives several ominous hints as to the development of the Stalinist terror and its impact in remote Alma-Ata.

Dombrovsky had begun publishing literary articles in Kazakhstanskaya Pravda by 1937, when he was imprisoned again — this time for a mere seven months, having the luck to be detained during the partial hiatus between the downfall of Yezhov and the appointment of Beria.

Dombrovsky's first novel Derzhavin was published in 1938 and he was accepted into the Union of Soviet Writers in 1939, the year in which he was arrested yet again. This time he was sent to the notorious Kolyma camps in northeast Siberia, of which we are given brief but chilling glimpses in The Faculty of Useless Knowledge.

Dombrovsky, partially paralysed, was released from the camps in 1943 and lived as a teacher in Alma-Ata until 1949. There he wrote The Monkey Comes for his Skull and The Dark Lady. In 1949, he was again arrested, this time in connection with the campaign against foreign influences and cosmopolitanism. This time, he received a ten-year sentence, to be served in the Tayshet and Osetrovo regions in Siberia.

In 1955, he was released and fully rehabilitated the following year. Until his death in 1978, he lived in Moscow with Klara Fazulayevna (a character in The Faculty of Useless Knowledge). He was allowed to write, and his works were translated abroad, but none of them were re-issued in the USSR. Nor was he allowed abroad, even to Poland.

The Faculty of Useless Knowledge (Harvill), translated by Alan Myers the sombre and chilling sequel to The Keeper of Antiquities took eleven years to write, and was published in Paris in 1978.

A widespread opinion is that this publication proved fatal. The KGB did not approve of the work, and it was noted that the book had actually been finished in 1975. Dombrovsky received numerous threats over the phone and through the post; his arm was shattered by a steel pipe in the course of an assault on a bus, and he was finally brutally beaten by a group of unknown persons in the lobby of the restaurant of the Central House of Writers in Moscow. Two months after the incident, on May 29, 1978 he died in hospital from severe internal bleeding caused by varicose veins of the digestive system.

An account about Dombrovsky written by Armand Maloumian, a fellow inmate of the GULAG, can be found in Kontinent 4: Contemporary Russian Writers (Avon Books, ed. George Bailey), entitled "And Even Our Tears."[2]

Jean-Paul Sartre described Yuri Dombrovsky as the last classic.[3]: 122

Bibliography

- 1939: Derzhavin (Alma-Ata: Kazakhstanskoe izdatel’stvo khudozhestvennnoi literatury, 1939)

- 1943: Obez'iana prikhodit za svoim cherepom [The Ape is coming to pick up its Skull] (Moscow: Sovetsky pisatel’, 1959)

- 1964: Khranitel' drevnostei [The Keeper of Antiquities] (Novyi mir magazine 1964, No 7-8).

- The Keeper of Antiquities (M. Glenny (trans.)) (London and Harlow: Longmans, 1969)

- The Keeper of Antiquities (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969)

- The Keeper of Antiquities (Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1988)

- The Keeper of Antiquities (London: Harper Collins [Harvill], 1991)

- 1969: Smuglaia ledi: tri novelly o Shekspire [The Dark Lady: Three Novellas About Shakespeare]

- 1970: Khudozhnik Kalmykov [The painter Kalmykov]

- 1973: Dereviannyi dom na ulitse Gogolia (1973) [The Wooden House on Gogol Street]

- 1974: Fakel (1974) [The Torch]

- 1975: Fakul'tet nenuzhnykh veshchei [The Faculty of Useless Knowledge] (Paris: YMCA-Press, 1978)

- The Faculty of Useless Things (Part 3 excerpted in Soviet Literature, July 1990, pp. 25–117, translated by Andrew Bromfield)

- The Faculty of Useless Knowledge (London: The Harvill Press, 1996)

- 1977: Ruchka, nozhka, ogurechik [A hand, a leg, a cucumber]. /That are words from popular kids song/ (Novyi mir magazine 1990, No 1)

References

- "Газета Информпространство - Архив 2006 № 3".

- "And Even Our Tears - About Yuri Dombrovsky by Armand Maloumian | Gulag | International Politics". Scribd. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- Dekterev, Tatiana (2010). "The Life and Poetics of Yury Dombrovsky Through Archival Documents and Letters and in the Context of Russian Modernism". Transcultural Studies. 6 (1): 117–142. doi:10.1163/23751606-00601009. ISSN 1930-6253. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

Further reading

- Doyle, Peter (2000). Iurii Dombrovskii: Freedom Under Totalitarianism. Studies in Russian and European literature. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Harwood Academic. ISBN 978-90-5702-624-9.

External links

- (in Russian) Works of Dombrovsky

- (in Russian) Dombrovsky's ethnic background

- (in Russian) Новая Газета #26, 22 мая 2008, Novaya Gazeta #26, 22 May 2008

- Толстой, Иван; Гаврилов, Андрей (2016-03-20). Алфавит инакомыслия. Юрий Домбровский. svoboda.org (in Russian). Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2016-04-03.