Yves Saint Laurent (designer)

Yves Henri Donat Mathieu-Saint-Laurent (1 August 1936 – 1 June 2008),[1] referred to as Yves Saint Laurent (/ˌiːv ˌsæ̃ lɔːˈrɒ̃/, also UK: /- lɒˈ-/, US: /- loʊˈ-/, French: [iv sɛ̃ lɔʁɑ̃] ⓘ) or YSL, was a French fashion designer who, in 1962, founded his eponymous fashion label. He is regarded as being among the foremost fashion designers of the twentieth century.[2] In 1985, Caroline Milbank wrote, "The most consistently celebrated and influential designer of the past twenty-five years, Yves Saint Laurent can be credited with both spurring the couture's rise from its 1960s ashes and with finally rendering ready-to-wear reputable."[3]

Yves Saint Laurent | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Saint Laurent in 1958 | |

| Born | Yves Henri Donat Mathieu-Saint-Laurent 1 August 1936 Oran, French Algeria |

| Died | 1 June 2008 (aged 71) Paris, France |

| Education | Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture |

| Occupation | Fashion designer |

| Label | Yves Saint Laurent |

| Partner | Pierre Bergé |

He developed his style to accommodate the changes in fashion during that period. He approached his aesthetic from a different perspective by helping women find confidence by looking both comfortable and elegant at the same time. He is also credited with having introduced the "Le Smoking" tuxedo suit for women and was known for his use of non-European cultural references and of diverse models.[4]

Early life

Saint Laurent was born on 1 August 1936, in Oran, Algeria,[5][6] to French parents (Pieds-Noirs), Charles and Lucienne Andrée Mathieu-Saint-Laurent.[7] He grew up in a villa by the Mediterranean with his two younger sisters, Michèle and Brigitte.[7] Saint Laurent liked to create intricate paper dolls, and by his early teen years, he was designing dresses for his mother and sisters.[8]

At the age of 18, Saint Laurent moved to Paris and enrolled at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, where his designs quickly gained notice. Michel De Brunhoff, the editor of Vogue France, introduced Saint Laurent to designer Christian Dior, a giant in the fashion world. "Dior fascinated me," Saint Laurent later recalled. "I couldn't speak in front of him. He taught me the basis of my art. Whatever was to happen next, I never forgot the years I spent at his side." Under Dior's tutelage, Saint Laurent's style continued to mature and gain even more notice.[8]

Personal life and early career

Young designer

In 1953, Saint Laurent submitted three sketches to a contest for young fashion designers organized by the International Wool Secretariat. Saint Laurent won first place. Subsequently, he was invited to attend the awards ceremony held in Paris in December of that same year.[9]

During his stay in Paris, Saint Laurent met Michel de Brunhoff, who was then editor-in-chief of the French edition of Vogue magazine and a connection to his father. Michel De Brunhoff, known by some as a considerate person who encouraged new talent, was impressed by the sketches that Saint Laurent brought with him and suggested he should intend to become a fashion designer. Saint Laurent eventually considered a course of study at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, the council which regulates the haute couture industry and provides training to its employees. Saint Laurent followed his advice and, left Oran for Paris after graduation, began his studies there and eventually graduated as a star pupil. Later, that same year, he entered the International Wool Secretariat competition again and won, beating out his friend Fernando Sánchez and young German student Karl Lagerfeld.[10]

Shortly after his win, he brought a number of sketches to de Brunhoff who recognized close similarities to sketches he had been shown that morning by Christian Dior. Knowing that Dior had created the sketches that morning and that the young man could not have seen them, de Brunhoff sent him to Dior, who hired him on the spot.[11]

Although Dior recognised his talent immediately, Saint Laurent spent his first year at the House of Dior on mundane tasks, such as decorating the studio and designing accessories. Eventually he was allowed to submit sketches for the couture collection. With every passing season, more of his sketches were accepted by Dior. In August 1957, Dior met with Saint Laurent's mother to tell her that he had chosen Saint Laurent to succeed him as a designer. His mother later said that she had been confused by the remark, as Dior was only 52 years old at the time. Both she and her son were surprised when Dior died at a health spa in northern Italy of a massive heart attack in October 1957.[10]

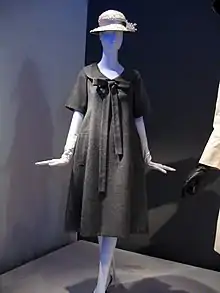

In 1957, Saint Laurent found himself at age 21 the head designer of the House of Dior. His spring 1958 collection almost certainly saved the enterprise from financial ruin.[12][13] The simple, flaring lines of his first collection for Dior, called the Trapeze line,[14][15] a variation of Dior's 1955 A-Line,[16][17][18] catapulted him to international stardom. Dresses in the collection featured a narrow shoulder that flared gently to a hem that just covered the knee.[19]

In his second collection for Dior, presented for fall 1958, he iconoclastically lowered hemlines by five inches and was not greeted with the same level of approval that his first collection received, with many considering it a major misstep.[20][21][22] Soon after, Marc Bohan was hired to assist St. Laurent,[23] and the spring 1959 Dior collection brought lengths back to the knee in a well-received collection inspired by the 1930s.[24] Later collections for the House of Dior featuring hobble skirts (fall 1959) [25][26] and beatnik fashions (fall 1960)[27][28] were savaged by the press.[29]

In 1959, he was chosen by Farah Diba, who was a student in Paris, to design her wedding dress for her marriage to the Shah of Iran.[30]

Conscription and illness

In 1960, Saint Laurent found himself conscripted to serve in the French Army during the Algerian War.[31] Neri Karra writes that there was speculation at the time that Marcel Boussac, the owner of the House of Dior and a powerful press baron, had put pressure on the government not to conscript Saint Laurent in 1958 and 1959, but after the disastrous Fall 1958 season, reversed course and asked that the designer be conscripted so that he could be replaced.[32]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_-_31940295547.jpg.webp)

Saint Laurent was in the military for 20 days before the stress of hazing by fellow soldiers led to him being admitted to a military hospital, where he received news that he had been fired from Dior, to be replaced by Marc Bohan.[33] This exacerbated his condition, and he was transferred to Val-de-Grâce military hospital, where he was given large doses of sedatives and psychoactive drugs and subjected to electroshock therapy.[34] Saint Laurent himself traced the origin of both his mental problems and his drug addictions to this time in hospital.[10]

YSL

After his release from the hospital in November 1960, Saint Laurent sued Dior for breach of contract and won. After a period of convalescence, he and his partner, industrialist Pierre Bergé, started their own fashion house, Yves Saint Laurent or YSL, with funds from American millionaire J. Mack Robinson,[35] cosmetics company Charles of the Ritz, and others.[36] Many Dior staff joined him at his new enterprise.[37] Saint Laurent and Bergé split romantically in 1976 but remained business partners.[38]

In the 1960s, Saint Laurent popularized fashion trends such as the beatnik look (1961),[39][40] safari jackets for men and women (1967),[41] pea coats (1962),[42] tall, thigh-high boots (1963, via his chosen shoe designer Roger Vivier),[43] and arguably the most famous classic tuxedo suit for women, Le Smoking (1966).[44][45] Many of his designs were inspired by women's lives in the sociopolitical climate of the time, particularly the trousers he showed in 1968 after witnessing the epochal French uprisings of that year.[46][47] Saint Laurent is often said to have been the main designer responsible for making more widely acceptable the wearing of pants by women.[48][49][50]

Yves Saint Laurent brought in new changes to the fashion industry in the 60s and the 70s. The French designer opened his prêt-à-porter house YSL Rive Gauche in 1967, where he was starting to shift his focus from haute couture to ready-to-wear. One of the purposes was to provide a wider range of fashionable styles being available to choose from in the market, as they were affordable and cheaper.

He was the first French couturier to come out with a full prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) line; although Alicia Drake credits this move with Saint Laurent's wish to democratize fashion;[51] others point out that other couture houses were preparing prêt-à-porter lines at the same time – the House of Yves Saint Laurent merely announced its line first. The first of the company's Rive Gauche stores, which sold the prêt-à-porter line, opened on the rue de Tournon in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, on 26 September 1966. The first customer was Catherine Deneuve.[10] He ended up doing many costumes for her in films such as Heartbeat, Mississippi Mermaid, and Love to Eternity.[52]

During the 1970s, Saint Laurent came to be considered the most prominent designer in the world,[53][54] adapting his designs to modern women's needs.[55][56] Even in his sometimes lavish Russian peasant collections of the middle of the decade, the clothes themselves remained comfortable and wearable.[57][58][59] He is also credited with initiating in 1978 the prominently shoulder-padded styles that would characterize the 1980s.[60][61]

Many of his collections were positively received by both his fans and the press, such as the autumn 1966 collection, which introduced Le Smoking tailored tuxedo suit, and his 1965 Mondrian collection. Other collections raised controversy, such as his spring 1971 collection, which was inspired by 1940s fashion. Though 1930s and '40s revival had been a trend among some London designers like Ossie Clark since the late sixties[62] and although Saint Laurent had presented a few 1940s looks late in the previous year,[63] for a designer of his stature to devote an entire couture collection to the 1940s raised some hackles. Some felt it romanticized the German occupation of France during World War II, which he did not experience, while others felt it brought back the unattractive utilitarianism of the time. The French newspaper France Soir called the spring 1971 collection "Une grande farce!"[10] Criticism notwithstanding, Saint Laurent's influence was such that the collection did lead to some general fashion changes in shoulder and lapel shape and increased the popularity of tailored blazers.[64]

During the 1960s and 1970s, Saint Laurent was considered one of Paris's "jet set".[51] He was often seen at clubs in France and New York City, such as Regine's and Studio 54, and was known to be both a heavy drinker and a frequent user of cocaine.[10] When he was not actively supervising the preparation of a collection, he spent time at his villa in Marrakech, Morocco. In the late 1970s, he and Bergé bought a neo-gothic villa, Château Gabriel in Benerville-sur-Mer, near Deauville, France. Yves Saint Laurent was a great admirer of Marcel Proust who had been a frequent guest of Gaston Gallimard, one of the previous owners of the villa. When they bought Château Gabriel, Saint Laurent and Bergé commissioned Jacques Grange to decorate it with themes inspired by Proust's Remembrance of Things Past.[65]

The prêt-à-porter line became extremely popular with the public if not with the critics and eventually earned many times more for Saint Laurent and Bergé than the haute couture line. However, Saint Laurent, whose health had been precarious for years, became erratic under the pressure of designing two haute couture and two prêt-à-porter collections every year. He increasingly turned to alcohol and drugs.[66] At some shows, he could barely walk down the runway at the end of the show, and he had to be supported by models.[67]

Following his 1978 introduction of the big-shoulder-pad looks[68] that would dominate the 1980s, he relied on a restricted set of styles based largely on big-shouldered jackets, narrow skirts and trousers, and pumps[69][70] that didn't vary much during the decade,[71][72][73] resulting in some fashion writers bemoaning the loss of his former inventiveness[74][75][76] and others welcoming the familiarity.[77][78] After a disastrous 1987 prêt-à-porter show in New York City, which featured US$100,000 jeweled casual jackets only days after the "Black Monday" stock market crash, he turned over the responsibility of the prêt-à-porter line to his assistants. Although the line remained popular with his fans, it was soon dismissed as "boring" by the press.[10]

Later life

A favorite among his female clientele, Saint Laurent had numerous muses that inspired his work. Among them were: French model Victoire Doutreleau,[79] who opened his first fashion show in 1962;[80] Loulou de la Falaise,[79][81] the daughter of a French marquis and an Anglo-Irish model, who became the jewelry designer for the brand;[82] Betty Catroux,[79][81] the half-Brazilian daughter of an American diplomat, who Saint Laurent considered his "twin sister";[83] French actress Catherine Deneuve;[79][81] French model Danielle Luquet de Saint Germain,[84] who inspired the Le Smoking suit;[85] American-French artist Niki de Saint Phalle, who also inspired the Le Smoking suit;[45] Mounia,[79][81] a model from Martinique who was the oft-used bride at his fashion shows; Lucie de la Falaise,[86][87] a Welsh-French model and niece of Loulou, who was the bride in his fashion shows in 1990–1994; jewelry designer Paloma Picasso;[79][81] Dutch actress Talitha Getty;[88][89] American socialite Nan Kempner,[90][91] who was named ambassador for the brand;[92] Italian model Marina Schiano,[79][81] who managed the YSL boutiques in North America; French model Nicole Dorier,[93] who became the director of his runway shows,[94] and later, the "memory" of his house when it became a museum; and French model Laetitia Casta,[95] who was the bride in his fashion shows in 1998–2001.[96]

In 1983, Saint Laurent became the first living fashion designer to be honored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art with a solo exhibition. In 2001, he was awarded the rank of Commander of the Légion d'Honneur by French President Jacques Chirac. Saint Laurent retired in 2002 and became increasingly reclusive.[97] In 2007, he was awarded the rank of Grand officier de la Légion d'honneur by French President Nicolas Sarkozy.[98][99] He also created a foundation with Bergé in Paris to trace the history of the house of YSL, complete with 15,000 objects and 5,000 pieces of clothing.[100]

Death

Saint Laurent died on 1 June 2008 of brain cancer at his residence in Paris.[101] According to The New York Times,[102] a few days prior, he and Bergé had been joined in a same-sex civil union known as a Pacte civil de solidarité (PACS) in France. When Saint Laurent was diagnosed as terminal, with only one or two weeks left to live, Bergé and the doctor mutually decided that it would be better for him not to know of his impending death. Bergé said, "I have the belief that Yves would not have been strong enough to accept that."[103]

He was given a Catholic funeral at Église Saint-Roch in Paris.[104] The funeral attendees included the former Empress of Iran Farah Pahlavi, Bernadette Chirac, Catherine Deneuve, and President Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife, Carla Bruni.[105]

His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in Marrakech, Morocco, in the Majorelle Garden, a residence and botanical garden that he owned with Bergé since 1980 and often visited to find inspiration and refuge.[106] Bergé said at the funeral service (in French): "But I also know that I will never forget what I owe you and that one day I will join you under the Moroccan palms."

Legacy

In February 2009, an auction of 733 items was held by Christie's at the Grand Palais, ranging from paintings by Picasso to ancient Egyptian sculptures. Saint Laurent and Bergé began collecting art in the 1950s. Before the sale, Bergé commented that the decision to sell the collection was taken because, without Saint Laurent, "it has lost the greater part of its significance", with the proceeds proposed for the creation of a new foundation for AIDS research.[107]

Before the sale commenced, the Chinese government tried to stop the sale of two of twelve bronze statue heads taken from the Old Summer Palace in China during the Second Opium War. A French judge dismissed the claim and the sculptures, heads of a rabbit and a rat, sold for €15,745,000.[108] However, the anonymous buyer revealed himself to be Cai Mingchao, a representative of the PRC's National Treasures Fund, and claimed that he would not pay for them on "moral and patriotic grounds".[109] The heads remained in Bergé's possession[110] until acquired by François Pinault, owner of many luxury brands including Yves Saint Laurent. He then donated them to China in a ceremony on 29 June 2013.[111]

On the first day of the sale, Henri Matisse's painting Les coucous, tapis bleu et rose broke the previous world record set in 2007 for a Matisse work and sold for 32 million euros. The record-breaking sale realized 342.5 million euros (£307 million).[112] The subsequent auction, 17–20 November, included 1,185 items from the couple's Normandy villa. While not as impressive as the first auction, it featured the designer's last Mercedes-Benz car and his Hermès luggage.[113]

Forbes rated Saint Laurent the top-earning dead celebrity in 2009.[114]

Museum

His house in his hometown of Oran, where he lived until the age of 18, was bought by an Oran entrepreneur named Mohamed Affane. He restored and transformed it into a museum, which has been open since July 2022.[115] The period furniture has been recovered and replaced exactly as it was. Around 400 sketches by Yves Saint-Laurent are exhibited, along with childhood photos of the renowned designer.[116][117]

In popular culture

On film

- 2002: David Teboul's Yves Saint Laurent: His Life and Times[118]

- 2002: Yves Saint Laurent: 5 Avenue Marceau 75116 Paris[119]

- 2009: Pierre Thoretton's L'Amour Fou[120]

- 2014: Yves Saint Laurent[121]

- 2014: Saint Laurent[122]

Television

- 1965: Appeared on 24 October as a "mystery guest" on the American television game show What's My Line?[123]

Books

- 2014: Yves Saint Laurent: A Moroccan Passion, Pierre Bergé, illustrated by Lawrence Mynott, Abrams, ISBN 978-1419713491[124]

- 2017: Dior by YSL, Laurence Benaïm, photography by Laziz Hamani, Assouline, ISBN 9781614285991[125]

- 2020: Yves Saint Laurent: The Impossible Collection, Laurence Benaïm, Assouline, ISBN 9781614289425[126]

See also

References

- "Yves Saint Laurent Dies – Yves Saint Laurent Has Died in Paris Aged 71" Archived 3 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Agence France-Presse (via Nine News). (2 June 2008). Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- "Yves Saint Laurent, Who Has Died Aged 71, was, with Coco Chanel, regarded as the Greatest Figure in French Fashion in the 20th Century, and could be said to have Created the Modern Woman's Wardrobe". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- "Yves Saint-Laurent". Goodreads. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Yves Saint Laurent's body put to rest Archived 29 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Fashion Television.

- "Yves Saint Laurent". Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Yves Saint Laurent". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Yves Saint Laurent Biography". bio. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Yves Saint Laurent". Biography. 18 August 2020.

- "Yves Saint Laurent | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Rawsthorn, Alice (1996). Yves Saint Laurent: A Biography. Nan A. Talese/Doubleday (New York City); ISBN 0-385-47645-0

- "Debut at Dior". Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1948-1959". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 204–205. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

Yves Saint Laurent...at the age of 21 found himself perched upon the multi-million franc edifice of the most influential fashion house in the world....[W]ith his first collection,...he launched the [T]rapeze line....'Saint Laurent has saved France!' said the French headlines. 'The great Dior tradition will continue!'

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1958". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 251. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

For the nation's largest industry, the well-being of its most prominent couture house was of great social and economic importance....Saint Laurent's first collection...was a resounding success.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1958". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 246, 247. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

Saint Laurent's [T]rapeze line, backbone of his successful first collection for Dior.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1958". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 254. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Saint Laurent's first collection introduced a new silhouette, the wedge-shaped 'Trapeze'...

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1948-1959". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 204. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

...[W]ith his first collection,...[Saint Laurent] launched the [T]rapeze line – not too different from Dior's A line, but just different enough.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1955". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 239. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

Dior produces his new A line, a triangle widened from a small head and shoulders to a full pleated or stiffened hem.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1955". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 230. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Dior's...'A' line consisted of coats, suits and dresses flared out into wide triangles from narrow shoulders. The waistline was the cross bar of the A and could be positioned either under the bust in an Empire manner or low down on the hips.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1958". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 254. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

The dress sloped down from the shoulders to a widened hem just below the knee, maintaining a definite geometric line through precise tailoring.

- "Bohan is Hired By Dior as Aide to St. Laurent". The New York Times: 23. 8 August 1958. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

Bucking the trend toward kneecap-length skirts, St. Laurent dropped his hems to mid-calf or longer. Some viewers called the move a mistake.

- Peterson, Patricia (1 August 1958). "Fashion Trends Abroad, Paris: St. Laurent Drops Hem 5 Inches". The New York Times: 10. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

...Yves St. Laurent...shocked us with his mid-calf skirts, which were about five inches longer than those shown by other Paris designers.

- "What to Look For in Paris Styles". The New York Times: 18. 5 August 1958. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

...American store buyers are asking [St. Laurent] to shorten the hems...

- "Bohan is Hired By Dior as Aide to St. Laurent". The New York Times: 23. 8 August 1958. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

Marc Bohan...has been hired by the House of Christian Dior to help Yves St. Laurent turn out Dior fashions for New York and South America...

- Donovan, Carrie (30 January 1959). "Fashion Trends Abroad, Paris: Dior Has the Feeling of the Thirties". The New York Times: 18. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

The spring collection, the third designed by young Yves St. Laurent, is full of the feeling of the Thirties....St. Laurent...now shows the same length that is shown all over Paris – an inch or two below the knee.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1959". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 259. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

Yves Saint Laurent at Dior raises the skirt to the knees...and pulls the skirt in to a tight knee-band....Vogue...show[ed] the hobble first in its 'least exaggerated'...form before leading up to the 'extreme trendsetter'.

- Donovan, Carrie (26 August 1959). "French Styles en Route: Dior Skirt Splits Critics". The New York Times: 32. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

...Yves Saint Laurent['s]...newly cut skirt...seemed to constrict the knees and then balloon above them. The skirt obviously was based on the hobble skirts of yore....The majority of the daily newspaper reporters immediately labeled it 'hobble'...

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1960". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 272. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

The beat look is the news at Dior...pale zombie faces; leather suits and coats; knitted caps and high turtleneck collars, black endlessly....Saint Laurent's...'beat' collection is the most unpopular look in Paris, and his last for Dior.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1960". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. pp. 262–263. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Saint Laurent's decision to interpret...youthful street fashion in expensive materials caused a furore at Dior...His Left Bank 'Beat Look' included black leather suits and coats, knitted caps, high turtleneck collars, and biker-style jackets in mink and crocodile skin....Saint Laurent had failed to court the buyers and press by gently evolving a line collection by collection.

- Hall, Harriet (16 December 2016). "Celebrating 70 years of Christian Dior: From the New Look to feminist slogans". Stylist. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Weller, Sheila (2015). The News Sorority: Diane Sawyer, Katie Couric, Christiane Amanpour -- and the (ongoing, Imperfect, Complicated) Triumph of Women in TV News. Penguin Books. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-14-312777-2.

- "5 Must-Know Tales About The Late Yves Saint Laurent". Vogue Arabia. 1 August 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Karra, Neri (28 November 2021). Fashion Entrepreneurship: The Creation of the Global Fashion Business. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-315-45875-5.

- "Marc Bohan Appointed Dior's New Designer". The New York Times: 38. 29 September 1960. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

The fashion house of Christian Dior...has bestowed the ultimate glory on...Marc Bohan. It has been announced that Bohan will replace...Yves Saint Laurent as chief designer.

- The Biography Channel – Yves Saint Laurent Biography Archived 6 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Torpy, Bill. "Metro Atlanta Business News". ajc.com. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1962". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

He received financial backing from a variety of sources, including a businessman from Georgia and the cosmetics company Charles of the Ritz...

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1962". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 268. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

...Saint Laurent...was joined by many of the staff from Dior when he opened his own house.

- Cole, Shaun (2002). "Saint Laurent, Yves". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1961". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 276. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

His autumn [1961] collection brings the Left Bank into the couture with total success.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1963". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 277. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

Saint Laurent's 1960 beat look was belatedly adapted: Samuel Robery showed simple leather shifts, Scaasi presented black alligator trousers, Ellen Brooke used black lacquered alligator for windbreaker jackets, and mock alligator was chosen by Modelia for polo coats and by David Kidd for short coats.

- "First Safari Jacket". Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

Yves Saint Laurent first introduced the safari jacket in his 1967 runway shows. However, it was a one-off design created for a photo-essay for Vogue (Paris) the following year that made the design famous and quickly turned it into a classic.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1978). "1962". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 271. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

The most important coat to come out of the couture this year [1962] was Saint Laurent's 'pea jacket.' Modelled on the sailor's traditional double-breasted garment and already an American classic, it now gained lasting international popularity.

- Peake, Andy (2018). "Chapeau Melon et Bottes de Cuir". Made for Walking. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Fashion Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7643-5499-1.

Yves Saint Laurent's fall...1963...visored caps, black leather jerkins, and Roger Vivier's towering cuissardes [thigh-high boots] in black crocodile...gave what [the Daily Mail's Iris] Ashley called 'a real space girl effect...'

- "First Tuxedo". Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

In his Autumn-Winter 1966 collection, Yves Saint Laurent introduced his most iconic piece: the tuxedo....[T]he Saint Laurent Rive Gauche version was a success. The label's younger clientele was quick to purchase it, making the tuxedo a classic. Saint Laurent would go on to include it in each of his collections until 2002.

- Emerson, Gloria (5 August 1966). "A Nude Dress That Isn't: Saint Laurent in a New, Mad Mood". The New York Times: R53. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

Niki de Saint-Phalle, an American artist living in [France], has had the best influence of all on Saint Laurent...Miss Saint-Phalle...always wears trouser suits with...boots....Now Saint Laurent has copied her 'black tie' trouser suit in velvet and in wool....In wool, it has a very ruffly white shirt, a big black bow at the neck, a wide cummerbund of satin, and satin stripes down the rather wide pants. It is worn with...satin boots.

- Morris, Bernadine (15 August 1976). "Fashion: Paris Report". The New York Times. p. 179. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

In the late 1960's, [Saint Laurent] watched the student riots in Paris and came up with the pants suit, which everyone is still wearing.

- Morris, Bernadine (16 September 1968). "Saint Laurent Has a New Name for Madison Avenue – Rive Gauche". The New York Times: 54. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

During the student upheavals in Paris in May [1968], [Saint Laurent] saw the girls and boys behind the barricades dressed...in pants...'They looked beautiful...,' he said...'Fashion is not only couture....Events are more important.'...[In] his last Paris couture collection, shown in July,...[p]ants outfits overshadowed more conventional attire.

- Heathcote, Phyllis W. (1 January 1970). "Fashion and Dress". Britannica Book of the Year 1970: Events of 1969. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. p. 341. ISBN 0-85229-144-2.

Leading Paris couturier Yves St. Laurent, from whose influence the vogue for trousers could be said to have stemmed, continued to promote them in his spring and fall [1969] collections.

- Morris, Bernadine (7 October 1968). "Even the Restaurateurs Concede That Pants are Fashionable". The New York Times: 54. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

Pants...have the endorsement of...Yves Saint Laurent, who devoted a good part of his last Paris collection to them and now is selling them like blue jeans...The wider cut to the legs has won many adherents.

- Morris, Bernadine (4 December 1972). "Pants Have Come a Long Way, and They're Coming Further". The New York Times: 52. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

Yves Saint Laurent in Paris gave the [pants-wearing] movement cachet in 1968 when he showed a couture collection that was almost totally pants. The same year Kimberly, the knitwear concern when dresses were the backbone of many conservative American wardrobes, introduced its first pants suits.

- Drake, Alicia. The Beautiful Fall: Lagerfeld, Saint Laurent, and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris. Little, Brown and Company, 2006. p.49.

- "Yves Saint-Laurent". IMDb. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Donovan, Carrie (12 November 1978). "Why the Big Change Now". The New York Times. p. SM226. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

...Yves Saint Laurent — the most influential fashion designer in the world...

- Hyde, Nina S. (21 September 1978). "Saint Laurent: On the Scent of a New 'Seduction'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

He is the most influential fashion designer in the world...

- Morris, Bernadine (12 April 1978). "Saint Laurent: The Clothes are the Message". The New York Times. p. C14. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

The reason why he is the most copied designer in the world is because he looks at the way people live and the way they dress and then tries to make them look a little better.

- Mulvagh, Jane (1988). "1968-1975". Vogue History of 20th Century Fashion. London, England: Viking, the Penguin Group. p. 296. ISBN 0-670-80172-0.

[Quote from Catherine Deneuve] 'Saint Laurent designs for women with double lives. His day clothes...permit her to go anywhere without attracting unwelcome attention...In the evening..., he makes her seductive.'

- Peake, Andy (2018). "The New Ease in Fashion". Made for Walking. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Fashion Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-7643-5499-1.

...[I]n 1974,...Saint Laurent created a Russian-themed collection....Saint Laurent's collection featured full skirts that fell below the knees, thick sweaters, capes, quilted gold jackets, velvet and satin knickerbockers, long fur coats and matching fur hats, and a new, and very distinctive, style of knee-length fashion boot...loose-fitting...

- Morris, Bernadine (7 April 1976). "Saint Laurent Was Hailed and Adored; For Kenzo, Tumult and Frency". The New York Times. p. 47. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

Next fall's peasants, according to Saint Laurent, will wear boots and babushkas...

- Freund, Andreas (8 August 1976). "The Empire of Saint Laurent". The New York Times. p. 87. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

The noise about Saint Laurent's big silhouette and folkloric look served to enhance his reputation...

- Donovan, Carrie (12 November 1978). "Why the Big Change Now". The New York Times. p. 226. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

What Saint Laurent sprang on the fashion world last January when he introduced man‐tailored suit jackets with shoulders squared out with padding...has now become staple fashion in Italy, France and America.

- "1978 Broadway Suit Collection". Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris.

'YSL's...mannequin...got ovations every time she sauntered out on the runway in another version of the spencer jacket'.

- Howell, Georgina (1978). "1967-68". In Vogue: Sixty Years of Celebrities and Fashion from British Vogue. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd. p. 296. ISBN 0-14-00-4955-X.

Ossie Clark...turns to the recent past for fawn jersey tailored suits with square shoulders, a forties-through-sixties-eyes look.

- Morris, Bernadine (24 July 1970). "Saint Laurent, Ungaro and Dior: Many Styles, No New Look". The New York Times: 37. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

Yves Saint Laurent was good for a few laughs...An obvious tart...sashayed through the salon. She represented the spirit of the nineteen-forties....The first spurts of laughter were followed by nervous reflection....Was Saint Laurent making fun of the nineteen-forties – or the audience? Or was the whole collection one big parody of fashion?

- Sweetinburgh, Thelma (1 January 1972). "Fashion". The 1972 Compton Yearbook: A Summary and Interpretation of the Events of 1971 to Supplement Compton's Encyclopedia. F. E. Compton Co., William Benton. p. 249. ISBN 0-85229-169-8.

...Saint Laurent's 1940's revival had its effect. As it turned out, the tailored style came back, with a slightly lifted shoulderline and wider, more pointed lapels, and the blazer became a mainstay of U.S. fashion in the fall.

- Grange, Jacques (21 October 2009). "An Introduction to Château Gabriel". Christie's. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Horyn, Cathy (24 December 2000). "Yves of Destruction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- "'Saint Laurent': Another view of the great fashion designer". The Seattle Times. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Larkin, Kathy (1 January 1979). "Fashion". 1979 Collier's Yearbook Covering the Year 1978. Crown-Collier Publishing Company. pp. 251–252.

...Saint Laurent...confirmed huge shoulders, puffed sleeves to emphasize width further...

- Morris, Bernadine (30 August 1981). "The Ultimate Luxury". The New York Times. p. 206. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

Saint Laurent emphasized suits that were squared at the top and tapering to the hem, like a triangle standing on its point.

- Donovan, Carrie (31 March 1985). "Fashion: Feminine Flourishes". The New York Times. p. 80. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

Karl Lagerfeld..., Yves Saint Laurent, Emanuel Ungaro and Hubert de Givenchy...continued with their versions of the rather aggressive broad-shouldered silhouette...

- Russell, Mary (8 April 1979). "Fashion/Beauty Fallout from Paris". The New York Times. p. SM19. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

Yves Saint Laurent has retreated into an autocritical contemplation of his years as the established 'No. 1' of Paris fashion. These days, he is creating refined and rethought versions of his legendary look.

- Donovan, Carrie (6 May 1979). "American Designers Come of Age". The New York Times. p. 254. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

...Saint Laurent may have reached the point where he feels that he has made his basic contribution to fashion and that now, like Chanel who kept on and on with her famous suit — he wants to reinforce his legend.

- Hyde, Nina (6 December 1983). "YSL". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

Saint Laurent says the day of big fashion changes is over. What he cares about is refining the classic, the basics, perfecting what he has already put into the fashion vernacular.

- Donovan, Carrie (22 June 1986). "Paris Cachet: Infinite Ideas". The New York Times. p. 39. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

Saint Laurent's...ready-to-wear efforts have been slowly sagging season after season.

- Cunningham, Bill (1 March 1986). "Bright New Fashion Takes a Brave New Direction". Details. Vol. IV, no. 8. New York, NY: Details Publishing Corp. p. 90. ISSN 0740-4921.

Yves Saint Laurent, the acknowledged king of the status quo in Europe, may have been a revolutionary in his early days...Now, however, St. Laurent has imposed a paralyzing primness...that suggests a retreat to the philistine cathedral of acceptable good taste.

- Cunningham, Bill (1 March 1988). "Fashionating Rhythm". Details. Vol. VI, no. 8. New York, NY: Details Publishing Corp. p. 121. ISSN 0740-4921.

The saddest moment of the spring ready-to-wear collections was the hackneyed offering of Yves Saint Laurent. What a pathetic decline for the former king of world fashion, who dominated design for...twenty years. One couldn't believe that the same man was responsible for what was paraded before the buyers and press. The loss of Saint Laurent's legendary color mixing, the rehash of decade-old designs, the afterthought accessories, left the audience confounded. One wanted to believe that Saint Laurent was not involved....[H]e appeared to have lost a very rare gift – his creative talent.

- Hyde, Nina (27 October 1988). "YSL, At the Ready". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

...Saint Laurent revived things from past collections to assure his customers that they can keep on wearing his styles no matter what the year.

- Hyde, Nina S. (2 April 1980). "The Phases of Yves". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

When did he first do the Mondrian styles? When was the first smoking jacket? How about the first tiered challis printed baby dress, the first cowboy styles, the first ruffled peasant styles? If you didn't remember exactly, it didn't matter, since the current versions, while new, look familiar enough to be the original versions.

- Smith, Kennedy (1 August 2021). "The Female Muses Who Inspired Yves Saint Laurent". CR Fashion Book. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- Betts, Hannah (16 March 2014). "Saint Laurent: the man and his muses". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- Berker, Elsa de (1 August 2020). "YSL Muses Throughout History". CR Fashion Book. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- Cheng, Andrea (27 April 2018). "Untold Stories About Loulou de La Falaise, Yves Saint Laurent's Lifelong Muse". CR Fashion Book. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- Veronica, Horwell (8 November 2011). "Loulou de la Falaise obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- "Yves Saint Laurent muse auctioning off massive wardrobe in Paris". New York Daily News. 14 October 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- Szmydke, Paulina (1 May 2013). "Danielle Luquet de Saint Germain to Auction Couture Collection". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- Alexander, Ella (11 February 2016). "The Next Generation: Talented Kids From A-List Royalty". Glamour UK. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Dupuis, Marion (21 April 2015). "Lucie de la Falaise, instants de grâce" [Lucie de la Falaise, moments of grace]. Madame Figaro (in French). Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- Thurman, Judith (11 March 2002). "Swann Song". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Anderson, Kristin; Taufield, Elizabeth (18 October 2016). "5 Gypset-Luxe Looks Worthy of Talitha Getty". Vogue. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Horwell, Veronica (25 July 2005). "Obituary: Nan Kempner". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Solomont, Elizabeth (12 June 2007). "From Met to Thrift Shop Sale: Nan Kempner's Haute Couture". The New York Sun. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- d'Annunzio, Grazia (September 2014). "Nan Kempner - Vogue.it". Vogue Italia. No. 769. p. 534. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- La Ferla, Ruth (16 July 2014). "Casting the Catwalk, Saint Laurent Style". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Roberts, Genevieve (22 February 2009). "The unique sell of YSL: Fashion king's art auction". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Mallard, Anne-Sophie (19 April 2012). "Laetitia Casta in 15 unforgettable runway moments". Vogue Paris. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Zahm, Olivier (Spring 2011). "Laetitia Casta". Purple Magazine. No. 15. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Thurman, Judith (2008). Cleopatra's Nose: 39 Varieties of Desire. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4299-2300-2.

- "Yves Saint Laurent Devient Grand Officier de la Legion D'Honneur !". Marie Claire (in French). 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Obituary: Yves Saint Laurent". The Telegraph. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent Foundation | champs-elysees-paris.org". www.champs-elysees-paris.org. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- "Tributes for Yves Saint Laurent". BBC News. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- France Salutes the Ultimate Couturier New York Times.

- "Pierre Bergé: "Yves Died at the Right Time"". The Talks. 22 February 2012.

- "Catholic farewell for YSL". CathNews. 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Empress Farah Pahlavi attends the funeral services of fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent on June 5". Farah Pahlavi website. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Yves Saint Laurent's Ashes Scattered In Marrakesh". Reuters. 12 June 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- WW, FashionNetwork com. "Proceeds of Saint Laurent sale to battle AIDS". FashionNetwork.com.

- "features in upcoming Christie's auctions". Christies.com. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "China 'patriot' sabotages auction". BBC News. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- McDonald, Mark; Vogel, Carol (2 March 2009). "Twist in Sale of Relics Has China Winking". The New York Times. New York City.

- "Looted Bronzes Return To China: Animal Heads Were Taken From Beijing Palace In 1860". Huffington Post. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- "Record bids for YSL private art". BBC News. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- "Yves Saint Laurent auction items from Normandy hideaway up for sale". The Telegraph. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Matthew Miller (27 October 2009). "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities". Forbes.

- Métaoui, Fayçal (11 July 2022). "A Oran, la résidence de Yves Saint-Laurent reprend vie - 24H Algérie - Infos - vidéos - opinions" (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "EN IMAGES : Oran, source d'inspiration pour Yves Saint Laurent". Middle East Eye édition française (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- "Yves Saint-Laurent : restauration de sa maison natale à Oran". TSA (in French). 5 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Yves Saint Laurent: Time Regained (2002), retrieved 11 June 2021

- Yves Saint Laurent 5, Avenue Marceau 75116 Paris (2002), retrieved 11 June 2021

- Holden, Steven (12 May 2011). "The Passions and Demons of Yves Saint Laurent". The New York Times. p. C12. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- Diderich, Joelle (10 January 2014). "Yves Saint Laurent Biopic Wins Pierre Bergé's Approval". WWD. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Saint Laurent (2014), retrieved 11 June 2021

- "10-25-1965 What's My Line". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Yves Saint Laurent: A Moroccan Passion – Fashion – Abrams & Chronicle". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "Dior by YSL". ASSOULINE.

- "Yves Saint Laurent: The Impossible Collection". ASSOULINE.

Further reading

- Bergé, Pierre (1997). Yves Saint Laurent: The Universe of Fashion. Rizzoli. ISBN 0-7893-0067-2.

- Milbank, Caroline Rennolds (1985). Couture: The Great Fashion Designers. Thames & Hudson.

- Rawsthorn, Alice (1996). Yves Saint Laurent: A Biography. Nan A. Talese/Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47645-0.

External links

- ysl.com, official Yves Saint Laurent (brand) website

- Trapèze dresses at Digital Collections at Chicago History Museum Archived 12 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- "Yves Saint Laurent, legendary designer and Pied Piper of fashion, dies aged 71", The Guardian: retrospective article

- "Interactive timeline of couture houses and couturier biographies". Victoria and Albert Museum. 29 July 2015.

- Biography of Yves Saint Laurent

- Yves Saint Laurent Biography

- "Yves Saint Laurent shuts its doors" – BBC World 31 October 2002

- "All About Yves" Archived 4 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Jim Lehrer 16 January 2002 By Jessica Moore

- "Yves Saint Laurent announces retirement" – CNN 7 January 2002

- "All About Yves: As the incomparable Yves Saint Laurent celebrates his 40th anniversary as a couturier, the world salutes his genius." – Julie K.L. Dam, Time magazine, 3 August 1998.