Zara Yaqob

Zara Yaqob (Ge'ez: ዘርዐ ያዕቆብ;[lower-alpha 1] 1399 – 26 August 1468) was Emperor of Ethiopia, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty who ruled under the regnal name Kwestantinos I (Ge'ez: ቈስታንቲኖስ, "Constantine"). He is known for the Ge'ez literature that flourished during his reign, the handling of both internal Christian affairs and external wars with Muslims, along with the founding of Debre Birhan as his capital. He reigned for 34 years and 2 months.[3]

| Zara Yaqob ዘርዐ ያዕቆብ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negusa Nagast | |||||

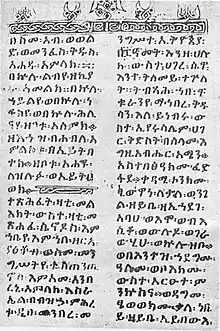

17th century Ethiopian portrait of Zara Yacob's coronation | |||||

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |||||

| Reign | 1434–1468 | ||||

| Coronation | 1436 | ||||

| Predecessor | Amda Iyasus | ||||

| Successor | Baeda Maryam I | ||||

| Born | 1399 Telq, Fatagar, Ethiopian Empire | ||||

| Died | 26 August 1468 (aged 68–69) Debre Berhan, Ethiopian Empire | ||||

| Spouse | Eleni Seyon Morgasa Gera Ba'altihat[1] | ||||

| Issue | Baeda Maryam I Galawdewos[2] Amda Maryam[2] Zar'a Abraham[2] Batra Seyon[2] Del Samera[2] Rom Ganayala[2] Adal Mangesha[2] Berhan Zamada[1] Madhen Zamada[1] Sabala Maryam[1] Del Debaba[1] | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Solomon | ||||

| Father | Dawit I | ||||

| Mother | 'Egzi'e Kebra[3] | ||||

| Religion | Ethiopian Orthodox Church | ||||

The British historian, Edward Ullendorff, stated that Zara Yaqob "was unquestionably the greatest ruler Ethiopia had seen since Ezana, during the heyday of Aksumite power, and none of his successors on the throne – excepted only the emperors Menelik II and Haile Selassie – can be compared to him."[4]

Early life

Born at Telq in the province of Fatagar, Zara Yaqob hailed from the Amhara people, he was the youngest son of Emperor Dawit I by his wife, Igzi Kebra. His mother Igzi lost her first son and having been sick during her second pregnancy, prayed fervently to the Virgin Mary to keep her new child alive. Her prayers were answered and she gave birth to Zara Yaqob, who had this miracle recorded in the Ta'ammara Maryam, one of Zara Yaqob's chronicles written in Amharic.[5][6]

Paul B. Henze repeats the tradition that the jealousy of his older brother Emperor Tewodros I forced the courtiers to take Zara Yaqob to Tigray where he was brought up in secret, and educated in Axum and at the monastery of Debre Abbay.[7] While admitting that this tradition "is invaluable as providing a religious background for Zara Yaqob's career", Taddesse Tamrat dismisses this story as "very improbable in its details". The professor notes that Zara Yaqob wrote in his Mashafa Berhan that "he was brought down from the royal prison of Mount Gishan only on the eve of his accession to the throne."[8]

Upon the death of Emperor Dawit, his older brother Tewodros ordered Zara Yaqob confined on Amba Geshen (around 1414). Despite this, Zara Yaqob's supporters kept him a perennial candidate for Emperor, helped by the rapid succession of his older brothers to the throne over the next 20 years, which left him as the oldest qualified candidate.[9] David Buxton points out the effect that his forced seclusion had on his personality, "deprived of all contact with ordinary people or ordinary life." Thrust into a position of leadership "with no experience of the affairs of state, he [Zara Yaqob] was faced by a kingdom seething with plots and rebellions, a Church riven with heresies, and outside enemies constantly threatening invasion." Buxton continues,

- In the circumstances it was hardly possible for the new king to show adaptability or tolerance or diplomatic skill, which are the fruit of long experience in human relationships. Confronted with a desperate and chaotic situation he met it instead with grim determination and implacable ferocity. Towards the end of his life, forfeiting the affection and loyalty even of his courtiers and family he became a lonely figure, isolated by suspicion and mistrust. But, in spite of all, the name of this great defender of the faith is one of the most memorable in Ethiopian history.[10]

Reign

Although he became Emperor in 1434, Zara Yaqob was not crowned until 1436 at Axum, where he resided for three years.[11] During his first years on the throne, Zara Yaqob launched a strong campaign against survivals of pagan worship and "un-Christian practices" within the church. According to a manuscript written in 1784, he appointed spies to search and "smell out" heretics who admitted to worshipping pagan gods such as Dasek, Dail, Guidale, Tafanat, Dino and Makuawze.[2] These heretics were decapitated in public.[2] The spies also revealed that his sons Galawdewos, Amda Maryam, Zar'a Abraham and Batra Seyon, and his daughters Del Samera, Rom Ganayala and Adal Mangesha were heretics and thus they were all executed as a result.[2] He then issued a royal edit ordering every Christian to bear on his forehead a fillet inscribed "Belonging to the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit." And fillets had to be worn on the arms, that on the right being inscribed "I deny the Devil in [the name of] Christ God," and that on the left, "I deny the Devil, the accursed. I am the servant of Mary, the mother of the Creator of all the world." Any man who disobeyed the edict had his property looted and was either beaten or executed.[12]

The Ethiopian Church had been divided over the issue of Biblical Sabbath observance for roughly a century. One group, which was loyal to the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, believed that the day of rest should be observed only on Sunday, or Great Sabbath. Another group, the followers of Ewostatewos, believed with its founder that both the original seventh-day Sabbath (Saturday, or Lesser Sabbath) and Sunday should be observed. Zara Yaqob was successful in persuading two recently-arrived Egyptian Abuna, Mikael and Gabriel, into accepting a compromise aimed at restoring harmony with the House of Ewostatewos, as the followers of Ewostatewos were known. At the same time, he made efforts to pacify the House of Ewostatewos. While the Ewostathians were won over to the compromise by 1442, the two Abuns agreed to the compromise only at the Council of Debre Mitmaq in Tegulet (1450).[13]

Garad Mahiko, the son of the Hadiya ruler Garad Mehmad, refused to submit to Abyssinia. However, with the help of one of Mahiko's followers, the Garad was deposed in favor of his uncle Bamo. Garad Mahiko then sought sanctuary at the court of the Adal Sultanate. He was later slain by the military contingent "Adal Mabrak," who had been in pursuit. The chronicles record that the "Adal Mabrak" sent Mahiko's head and limbs to Zara Yaqob as proof of his death.[14] Zara Yaqob invaded Hadiya after they failed to pay the annual tribute exacted upon them by the Ethiopian Empire, and married its princess Eleni, who was baptized before their marriage.[15] Eleni was the daughter of the former king of the Hadiya Kingdom (one of the Muslim Sidamo kingdoms south of the Abay River), Garad Mehamed.[16] Although she failed to bear him any children, Eleni grew into a powerful political person. When a conspiracy involving one of his Bitwodeds came to light, Zara Yaqob reacted by appointing his two daughters, Medhan Zamada and Berhan Zamada, to these two offices. According to the Chronicle of his reign, the Emperor also appointed his daughters and nieces as governors over eight of his provinces. These appointments were not successful.[17]

After hearing about the demolition of the Egyptian Debre Mitmaq monastery, he ordered a period of national mourning and built a church of the same name in Tegulet. He then sent a letter of strong protest to the Egyptian Sultan, Sayf ad-Din Jaqmaq. He reminded Jaqmaq that he had Muslim subjects whom he treated fairly, and warned that he had the power to divert the Nile, but refrained from doing so for the human suffering it would cause. Jaqmaq responded with gifts to appease Zara Yaqob's anger, but refused to rebuild the Coptic churches he had destroyed.[18] The Sultan would then encourage the Adal Sultanate to invade the province of Dawaro to distract the Emperor, but Zara Yaqob managed to defeated Badlay ad-Din, the Sultan of Adal at the Battle of Gomit in 1445, which consolidated his hold over the Sidamo kingdoms in the south, as well as the weak Muslim kingdoms beyond the Awash River.[lower-alpha 2][19] Similar campaigns in the north against the Agaw and the Falasha were not as successful. He then established himself at Hamassien and Serae to strengthen the imperial presence in the area, he settled a group of warriors from Shewa in Hamassien as military settlers. These settlers were believed to have the terrified the local population and it is said that the earth "trembled at their arrival" and the inhabitants "fled the country in fear". It is during this time that the title of the coastal regions' ruler, Bahr Negash, first appears in records and according to Richard Pankhurst the office was likely introduced by Zara Yaqob.[20]

After observing a bright light in the sky (which most historians have identified as Halley's Comet, visible in Ethiopia in 1456), and believing it to be a sign from God, indicating His approval of the execution by stoning of a group of heretics 38 days earlier, Zara Yaqob established Debre Berhan as his capital for the duration of his reign. He ordered a church built on the site, and later constructed an extensive palace nearby, and a second church, dedicated to Saint Cyriacus.[lower-alpha 3] He later returned to his native village of Telq in the province of Fatager and built a church dedicated to Saint Michael. He then built two more churches, Martula Mikael and 'Asada Mikael, before returning to Debre Berhan.[21]

In his later years, Zara Yaqob became more despotic. When Takla Hawariat, abbot of Dabra Libanos, criticized Yaqob's beatings and murder of men, the emperor had the abbot himself beaten and imprisoned, where he died after a few months. Zara Yaqob was convinced of a plot against him in 1453, which led to more brutal actions. He increasingly became convinced that his wife and children were plotting against him, and had several of them beaten. Seyon Morgasa, the mother of the future emperor Baeda Maryam I, died from this mistreatment in 1462, which led to a complete break between son and father. Eventually relations between the two were repaired, and Zara Yaqob publicly designated Baeda Maryam as his successor. Near the end of his reign, in 1464/1465, Massawa and the Dahlak archipelago were pillaged by emperor Zara Yaqob, and the Sultanate of Dahlak was forced to pay tribute to the Ethiopian Empire.[22]

According to Richard Pankhurst, Zara Yaqob was also "reputedly an author of renown", having contributed to Ethiopian literature as many as three important theological works. One was Mahsafa Berha "The Book of Light", an exposition of his ecclesiastical reforms and a defence of his religious beliefs; the others were Mahsafa Milad "The Book of Nativity" and Mahsafa Selassie "The Book of the Trinity".[23] Edward Ullendorff, however, attributes to him only the Mahsafa Berha and Mahsafa Milad.[4]

In the sixteenth century Adal leader Ahmed ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi ordered the destruction of his former palace in Debre Birhan.[24]

Foreign affairs

Zara Yaqob sent delegates to the Council of Florence in 1441, and established ties with the Holy See and Western Christianity.[25] They were confused when council prelates insisted on calling their monarch Prester John. They tried to explain that nowhere in Zara Yaqob's list of regnal names did that title occur. However, the delegates' admonitions did little to stop Europeans from referring to the monarch as their mythical Christian king, Prester John.[26]

He also sent a diplomatic mission to Europe (1450), asking for skilled labour. The mission was led by a Sicilian, Pietro Rombulo, who had previously been successful in a mission to India. Rombulo first visited Pope Nicholas V, but his ultimate goal was the court of Alfonso V of Aragon, who responded favorably.[27] Two letters for Ethiopians in the holy land (from Amda Seyon and Zara Yaqob) survive in the Vatican library, referring to "the kings Ethiopia."

Notes

- Translates to "Seed of Jacob"

- His war against Badlay is described in the Royal Chronicles (Pankhurst 1967, pp. 36–38).

- The founding of Debre Berhan is described in the Royal Chronicles (Pankhurst 1967, pp. 36–38).

Citations

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume 1). London: Methuen & Co. p. 307.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume 1). London: Methuen & Co. p. 305.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume 1). London: Methuen & Co. p. 304.

- Ullendorff 1960, p. 69.

- Uhlig, Siegbert; Bausi, Alessandro; Yimam, Baye, eds. (2003). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 247. ISBN 9783447052382. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023.

- Danver, Steven L (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 15-16. ISBN 9781317464006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Henze 2000, p. 68.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, p. 222.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, pp. 278–283.

- Buxon 1970, pp. 48ff.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, p. 229.

- A. Wallace Budge, E. (1828). History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia. Vol. 1. Methuen & co. p. 300.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, p. 230.

- Pankhurst, Ethiopian Borderlands, pp. 143f

- Hassen 1983, p. 22.

- Braukämper, Ulrich (1977). "Islamic Principalities in Southeast Ethiopia Between the Thirteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (Part Ii)". Ethiopianist Notes. 1 (2): 1–43. JSTOR 42731322. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- Pankhurst 1967, p. 32.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, pp. 262–3.

- Henze 2000, p. 67.

- Pankhurst 1967, p. 101.

- A. Wallace Budge, E. (1828). History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia. Vol. 1. Methuen & co. p. 300.

- Connel & Killion 2011, p. 160.

- Pankhurst 2001, p. 85.

- Dabra Birhan. Encyclopedia Aethiopica. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Selassie 1977.

- Silverberg 1996, p. 189.

- Taddesse Tamrat 1972, p. 264ff.

Sources

- Buxon, David (1970). The Abyssinians. New York: Praeger. pp. 48ff.

- Connel, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. The Scarecrow. ISBN 978-081085952-4.

- Hassen, Mohammed (1983). The Oromo of Ethiopia, 1500–1850: with special emphasis on the Gibe region (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). University of London. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave. p. 68. ISBN 1-85065-522-7.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 85.

- Pankhurst, Richard K. P. (1967). The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles. Addis Ababa: Oxford University Press. p. 32.

- Selassie, Tsehai Berhane (1977). "Zare'a Ya'eqob, c. 1399 to 1468, Orthodox, Ethiopia". In Ofosu-Appiah, L. H. (ed.). The Encyclopaedia Africana Dictionary of African Biography. New York: Reference Publications. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016 – via Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

- Silverberg, Robert (1996). The Realm of Prester John (paperback ed.). Ohio University Press. p. 189. ISBN 1-84212-409-9.

- Tamrat, Taddesse (1972). Church and State in Ethiopia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-19-821671-8.

- Ullendorff, Edward (1960). The Ethiopians: An Introduction to the Country and People (second ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-19-285061-X.

Further reading

- Krebs, Verena (2019). "Crusading threats? Ethiopian-Egyptian relations in the 1440s". Croisades en Afriqe. Presses universitaires du Midi. pp. 245–274. ISBN 978-281070557-3. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2019.