Zaton, Šibenik-Knin County

Zaton is a settlement within the City of Šibenik.

Zaton | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Zaton | |

| Coordinates: 43°47′13″N 15°49′26″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Dalmatia |

| County | Šibenik-Knin County |

| First mentioned | 1322 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 20.5 km2 (7.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

| • Total | 929 |

| • Density | 45/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 22215 ZATON |

| Area code | +385 022 |

| Vehicle registration | ŠI |

Geography

Zaton is located in the northwestern part of the Šibenik bay at 43° 47' north latitude and 15° 49' east longitude. It is surrounded by the hills Rasovač (133 m), Križeva glava (102 m), Mali Vranik (116 m) and Veliki Vranik (142 m). Along the sea, from Dobri dolac cove to Šarina draga cove, there is a promenade about three kilometers long. On the northern coast are the beaches Zvizda and Šarina draga. There are several sources of fresh water in the village, which make the sea brackish.

.jpg.webp)

Economy

The economic basis is agriculture, fishing and tourism. Residents are also employed in Šibenik.[3]

Population

According to the 2021 census, Zaton has 929 inhabitants. The population is almost entirely Croatian by nationality, and almost entirely Catholic by religion.

The earliest data on the number of inhabitants according to Krsto Stošić:[4]

- 1709: 97

- 1774: 260

- 1810: 304

- 1845: 443

- 1901: 1044

- 1928: 1526

- 1939: 1600

Sport

Due to extremely favorable natural conditions, for the purposes of the 1979 Mediterranean Games, a high-quality rowing course with accompanying facilities was built in Zaton. Many national and other teams train on the course to this day.

Festivals

- Klapas on the Vrulja – end of July

- The Zaton Games – end of July / beginning of August

- The Feast of Saint Roch – the 16th of August

- The Zaton Pidočijada (mussel festival) – end of August / beginning of September[5]

History

Prehistory

On four occasions between 1888 and 1890, the local teacher Frane Škarpa explored the cave on Tradanj hill near the village. He found fragments of prehistoric vessels with various cuts and symmetrical cavities, Roman oil lamps, jugs and a gold coin of the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian from the first half of the 6th century. In 1971, the remaining part of the cave was investigated by archaeologist Zdenko Brusić, who confirmed that it is possible to trace the occasional visits of man from the Neolithic (6th millennium BC) to the late antique period. The cave was most intensively used during the Copper and Bronze Ages (from the middle of the 4th to the middle of the 2nd millennium BC).[6]

In the 1970s, Zdenko Brusić partially explored the cave in Šarina draga bay, where he found ceramics from the Cetina culture and the remains of Ice Age animals up to 50,000 years old. In 2014, a new research was started under the leadership of the archaeologists of the Šibenik City Museum, Emil Podrug and Dario Vujević from the Department of Archaeology of the University of Zadar. New research has shown that Šarina draga was a kind of hunting station or hunting camp that was used for killing animals and preparing meat in the late Paleolithic period. The remains of animal bones of wild cattle, deer and wild horses with traces of cutting, as well as flint knives, were found in the cave.[6]

Antiquity

Two to three kilometers northwest of Zaton is the Velika Mrdakovica hill with an archaeological site consisting of a hilltop settlement, a necropolis and a cistern. On the upper third of the hill there is a Liburnian-Roman settlement of an unknown name of about 8500 m2, which is often associated with the ancient city of Arauzon. The settlement existed from the 7th century BC to the end of the 2nd century AD. The necropolis is located southeast of the hilltop settlement, along the road that led to it. During systematic archaeological research (1969 – 1974, 2011 – 2014), about 140, mostly Roman – cremation, but also prehistoric – inhumation graves (7th – 1st century BC) were discovered, which were also used in antiquity, and one medieval burial. Southwest of the hilltop settlement there is a vaulted Roman cistern rectangular in shape with an entrance on the eastern side, built during the 1st – 2nd centuries, known as Ograđenica or Pišća. Today, it is the central place of happening for the Vodice Bacchanalia manifestation.

The Middle Ages

About two kilometers southeast of the village is the church of Our Lady of Srima from the 12th or 13th century.[7]

Zaton (in the form Zatocon) was first mentioned in 1322 in a charter by which the King of Hungary and Croatia Charles I confirmed the ownership privileges of the citizens of Šibenik in their former borders.[8][9]

In the vicinity of Zaton, at an unknown location, there was a village called Humljani from 1433 at the latest, whose inhabitants moved because of the danger from the Ottomans.[4]

The Early and the Late Modern Period

In 1496, Zaton belonged to the Parish of the Assumption, and in 1533, the Parish of St. George and the Brotherhood of St. Luke were founded. The Parish Church of St. George, which with its cemetery still stands in the center of the town, was built in 1666.[8]

According to Krsto Stošić, Zaton was under Ottoman occupation from 1576 to 1577.[4]

In the 16th century, there was a defensive tower in Zaton or in its vicinity, owned by the Šibenik noble family Tavilić. Krsto Stošić believes that the tower could have been located between Zaton and Vodice, in a place called Dabrovac, while Vjekoslav Kulaš places it in the bay itself, on an islet that was destroyed by a glider before the First World War in order to allow steamboats to dock at the waterfront.[4][9][8]

Glagolitic singing of the mass by the parish priest continued until 1817, and by the faithful until 1845.[8]

On November 24, 1884 a public school was opened with Frane Škarpa from Stari Grad as its first teacher.[8]

In 1894 a post office was opened.[9]

On June 16, 1906 the new cemetery on Strandraga hill was consecrated.[8]

On June 26, 1928 the construction of a new parish church began right next to the old one, and it was not fully completed until August 15, 1995.[8][9]

In August 1932 the local organization of the Communist Party of Croatia was founded in Zaton.[10]

In 1933 the local teacher Nikola Živković founded a reading room, which operated until the Italian occupation in 1941.[9]

World War II

On December 10, 1941, Italian troops settled permanently in Zaton for the first time. On March 31, 1943 the fascists abandoned their previous decision to burn the village down and decided to blockade it instead. On April 1, 1943 a ban on leaving homes from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. and leaving the village at any time under threat of shooting was enacted. The village was surrounded by barbed wire and concrete fortifications. On April 16, 1943 the nearby village of Raslina was burned down, and 450 homeless inhabitants of Raslina were brought to Zaton. On September 9, 1943 Italian troops left Zaton for good, and on October 20, 1943 the German army arrived to Zaton, and remained there until September 4, 1944. During the occupation, the Italian occupiers and the Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia committed numerous crimes against the population of Zaton, the most notable of which was the shooting of 11 women, 4 adult men and a 16-year-old boy at the local cemetery on June 13, 1943. During the occupation, 64 houses were burned down, and 580 inhabitants of Zaton passed through Italian camps, mainly through the Molat concentration camp. 193 inhabitants of Zaton died as anti-fascist fighters, 112 inhabitants were shot or died in prisons and camps, and 58 died of hunger during the blockade. Zaton had about 1700 inhabitants at the beginning of the war, and about 1000 at the end. A monument to anti-fascist fighters and victims of fascism was erected in the center of the village in 1953.[8][9][10][11]

Socialist Yugoslavia

In 1946 128 colonists from Zaton were sent to settle Stanišić, but by the end of 1948, all but one family had returned to Zaton.[9]

From 1946 to 1955 the Pobjeda Peasant Labor Cooperative operated in Zaton.[9]

During this period, many people from Zaton found employment in Šibenik's industry, especially in the overhaul shipyard.[9]

Electricity was introduced to Zaton in 1951, when the fire brigade was also founded, and running water was introduced in 1971.[9]

In the 1970s the library was established, and was systematized by the librarian Tome Živković Puilov.[9]

The Zaton Music was founded in 1983, and is still active today.[9]

On March 20, 1990 a branch of the Croatian Democratic Union was founded in Zaton.[9]

The Croatian War of Independence

On September 16, 1991 four men from Zaton, Mile Martinović, Ante Mrša Okac, Ivica Živković Čiko and Ante Kulaš, stopped a convoy of Yugoslav People's Army tanks in a private car near the Šibenik Bridge when Ante Kulaš hit a tank using an M80 Zolja.[9]

213 inhabitants of Zaton participated in the Croatian War of Independence on various battlefields. Three men from Zaton died in the battle: Darko Crnica, Vedran Čoga and Vinko Ševerdija. Marko Bilušić was killed by a cluster bomb as a civilian victim of the war. A monument to the victims was erected in the center of the village.[9]

Notable inhabitants

- Ante Crnica, canonist, promoted the canonization of Nicholas Tavelic

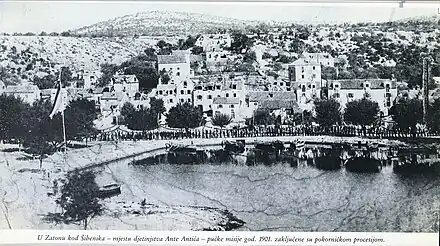

- Ante Antić, Servant of God, spent his childhood in Zaton

- Petar Bilušić, poet and storyteller

- Gabrijel Cvitan, writer

- Duško Ševerdija, poet, playwright and entrepreneur

- Grozdana Cvitan, writer

References

- Register of spatial units of the State Geodetic Administration of the Republic of Croatia. Wikidata Q119585703.

- "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2021 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- "Zaton | Hrvatska enciklopedija". www.enciklopedija.hr. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- Stošić, Krsto (2020). Sela šibenskoga kotara (in Croatian). Zagreb: Naklada Nediljko Dominović. pp. 26–30. ISBN 978-953-7954-50-5.

- "Slobodna Dalmacija - Stranci se ne mogu načuditi da su pidoće mukte". slobodnadalmacija.hr (in Croatian). 2023-09-07. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- Klisović, Marijana (2015). "Arheološki nalazi u speleološkim objektima Šibensko-kninske županije". Subterranea Croatica. 13 (2): 50–58 – via Hrčak.

- Dujmović, Frano; Fisković, Cvito (1959). "ROMANIČKE FRESKE U SRIMI". Prilozi povijesti umjetnosti u Dalmaciji. 11 (1): 12–40 – via Hrčak.

- Bareša, Ive (1996). Kronika župe Zaton kod Šibenika od 1322. do 1992 (in Croatian). Šibenik: Ive Bareša.

- Kulaš, Vjekoslav (2004). Šibenski Zaton u riječi i slici (in Croatian). Šibenik: Ogranak Matice hrvatske u Šibeniku. ISBN 953-6379-25-2.

- Gradiška, Vitomir (1969). Primorska četa (in Croatian). Šibenik: Muzej grada Šibenika.

- "Zaton kod Šibenika okružen bodljikavom žicom 01.04.1943". Antifašistički VJESNIK. Retrieved 2023-08-08.