Zeami Motokiyo

Zeami Motokiyo (世阿弥 元清) (c. 1363 – c. 1443), also called Kanze Motokiyo (観世 元清), was a Japanese aesthetician, actor, and playwright.

His father, Kan'ami Kiyotsugu, introduced him to Noh theater performance at a young age, and found that he was a skilled actor. Kan'ami was also skilled in acting and formed a family theater ensemble. As it grew in popularity, Zeami had the opportunity to perform in front of the Shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. The Shōgun was impressed by the young actor and began to compose a love affair with him.[1] Zeami was introduced to Yoshimitsu's court and was provided with an education in classical literature and philosophy while continuing to act. In 1374, Zeami received patronage and made acting his career. After the death of his father in 1385, he led the family troupe, a role in which he found greater success.

Zeami mixed a variety of Classical and Modern themes in his writing, and made use of Japanese and Chinese traditions. He incorporated numerous themes of Zen Buddhism into his works and later commentators have debated the extent of his personal interest in Zen. The exact number of plays that he wrote is unknown, but is likely to be between 30 and 50. He wrote many treatises about Noh, discussing the philosophy of performance. These treatises are the oldest known works on the philosophy of drama in Japanese literature, but did not see popular circulation until the 20th-century.

After the death of Yoshimitsu, his successor Ashikaga Yoshimochi was less favorable to Zeami's drama. Zeami successfully sought out patronage from wealthy merchants and continued his career under their support. He became well-known and well-respected in Japanese society. Ashikaga Yoshinori became hostile toward Zeami after becoming Shōgun in 1429. Yoshinori held Zeami's nephew Onnami in high regard, and disagreed with Zeami's refusal to declare Onnami his successor as leader of his troupe. Possibly due to this disagreement, though a variety of competing theories have been advanced, Yoshinori sent Zeami into exile to Sado Island. After Yoshinori's death in 1441, Zeami returned to mainland Japan, where he died in 1443.

Early life

Zeami was born in 1363[2] near Nara[3] and was known as Kiyomoto as a child.[2] A later genealogy mentions his mother as the daughter of a priest and a military official, but it is not deemed reliable.[3] His father Kanami led a theater troupe[2] which primarily performed in the Kyoto region,[4] before becoming popular in the late 1360s and early 1370s. As they became better-known, Kanami's troupe began to perform in Daijogi.[5] Zeami acted in the troupe and was considered attractive and highly skilled.[6]

Ebina no Naami, an adviser of the Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, booked the troupe to perform for the Shōgun, who was then 17 years old.[4] The shōgun was very powerful politically and was a patron of the arts.[7] He was impressed by the troupe, and patronized Kanami. The troupe began to focus on the entertainment value of performance, rather than its religious significance. It had been a form of entertainment associated with the country, but with Yoshimitsu's support it became associated with the upper class.[8] The Shōgun was highly attracted to Zeami, which proved controversial among aristocrats because of Zeami's lower-class background.[5] Yoshimitsu regularly invited Kanami and Zeami to the court, and Zeami accompanied him to events.[9] Due to his connection with the Shōgun, Zeami was provided with a classical education by court statesman and poet Nijo Yoshimoto.[10] Nijo was renowned for his skill as a Renga and taught Zeami about literature, poetry, and philosophy. This type of education was very unusual for an actor: due to their lower-class backgrounds, actors received little education.[7]

Career

Zeami received patronage in 1374, which was then an uncommon honor for an actor.[10] Patronage allowed him to become a vocational artist[11] and he began to lead the troupe after his father's death in 1385. The troupe became successful during his tenure as a leader.[12] While leading the troupe, he wrote the first Japanese treatises on pragmatic aesthetics.[4]

Zeami adhered to a formalist writing process: he began with a topic, determined the structure, and finished by writing the lyrics. The number of plays that he wrote is uncertain, and is estimated to be around 50 or 60.[13] His intellectual interests were eclectic[11] and he was a proficient writer of Renga.[14] The Tale of the Heike was the source of several of his best known plays.[15] He integrated Japanese and Chinese ancient poetry into his drama.[16] Contemporary dramatists Doami and Zoami had a significant influence on him,[17] earning recognition in his treatises. He spoke particularly well of Zoami,[7] but his shift toward Yugen and away from Monomane may have been because of Doami's influence.[18] He mixed popular dance, drama, and music with classical poetics and thus broadened and popularized the classical tradition.[4] In his earlier work, he used Zen illustrations, creating new Zen words and using established Zen words out of context. Many of the themes he used are present in other schools of Buddhism.[18] Japan was dominated by a focus on Zen culture then, and he was registered at a Zen temple[19] and was a friend of a well-known Zen priest.[18] In 1422, he became a lay monk.[20]

One of the most important performances of Zeami's career occurred in 1394. At that time, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu visited the Kasuga shrine in Nara and Zeami performed during the visit.[21] It was a significant political event, so Zeami was likely a well known artist then. He gave two significant performances for the Shōgun in 1399,[22] one of which could have been attended by Emperor Go-Komatsu.[23]

Zeami found Yoshimitsu to be a difficult patron,[23] and was rivaled by Inuo, a Sarugaku actor, for the favor of the Shōgun.[24] Though Yoshimitsu died in 1408,[24] and new Shōgun, Yoshimochi, was indifferent to Zeami[25] and preferred the dengaku work of Zoami,[7] Zeami's career remained strong[26] due to his connections with the urban commercial class. Due to his status as a well respected public figure, he had access to a number of patrons.[26] He eventually reached the stature of a celebrity[7] and wrote a significant amount between 1418 and 1428.[26]

Plays

Authorship of noh plays is a complex issue and often a matter of debate. Many plays have been attributed to Zeami, and he was known to be involved in revising and transmitting many others. Some plays are decisively known to have been written by him. His plays have been passed down through generations of Kanze leaders, as a result they have been revised and reworked from various leaders.[27] The following are universally attributed to Zeami:[28]

Treatises

Zeami produced 21 critical writings over a period of roughly four decades.[29] His treatises discuss the principles of Noh. He sought to inform his colleagues of the most important aspects of theater, discussing the education of the actor,[30] character acting, music, and physical movement.[31] They also discussed broader themes, such as how life should be lived.[32] The treatises were intended for a small circle of his colleagues, since the troupes were hereditary and such information was traditionally passed down between generations. He desired to facilitate this process[25] to ensure continued patronage for the troupe.[33]

Fūshikaden

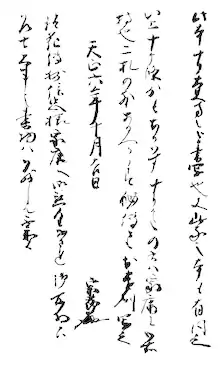

Zeami wrote several treatises on drama, the first of which was the Fūshikaden (風姿花伝, "The Transmission of the Flower Through (a Mastery of) the Forms", more loosely "Style and the Flower"), known colloquially as Kadensho (花伝書, "The Book of Transmission of the Flower"). It is the first known treatise on drama in Japan;[22] though similar treatises were written by Japanese Buddhist sects and poets, this is the Noh treatise. J. Thomas Rimer suggests that Zeami's education in Renga poetry provided him with the idea.[33] It notably includes a thorough analysis of jo-ha-kyū, which Zeami viewed as a universal concept. His first treatise includes much of his father's views of Noh.[22]

Kakyo

The treatise Kakyo was written later and describes Zeami's personal views. Though Fushikaden discusses flowers at length, Kakyo deals with spiritual beauty and contains discourses on the voice of the actor and the actors' minds.[17] A possible interest in Zen has been credited with this shift by some scholars.[18] The change in his age between his first and last works also appears to have significantly affected his perspective.[19] He spent a significant amount of time writing Kakyo and gave the completed work to his son Motomasa,[34] Zeami's son Motoyoshi had previously transcribed Zeami's treatise Reflections on Art.[25]

Decline

After Ashikaga Yoshinori became the Shōgun, he demonstrated a deeper disdain for Zeami than his predecessors had,[19] though the origins of his feelings are unknown. Speculation has centered on Zeami's association with Masashige[19] and the theory that Zeami was a restorationist.[4] In 1967, the Kanze-Fukudu genealogy was found and gave credence to the idea that politics contributed to Yoshinori's treatment of Zeami. The genealogy showed that a brother of Zeami's mother was a supporter of the southern court against the Ashikaga Shogunate.[2] Yoshinori is sometimes seen as eccentric, and it has been speculated that he punished Zeami because he did not enjoy his performances. (Yoshinori preferred colorful plays[35] that involved actors portraying demons; these types of plays were seldom found in Zeami's repertoire.)[36] Yoshinori, who enjoyed Monomane, preferred Onnami,[35] as his performances included demons.[36] Zeami had been close with his Onnami and they had performed together.[36] Zeami had been unsure whether any of his sons would be able to lead the troupe after his death, so he paid special attention to Onnami's development.[37] Motomasa, however, began to lead the troupe in 1429.[37] That year, though Motomasa and Onnami each performed for Yoshinori during a 10-day festival[38] Yoshinori forbade Zeami to appear at the Sentō Imperial Palace,[19] possibly due to his refusal to provide Onnami with his complete writings.[37] The next year, the music directorship of the Kiyotaki shrine was transferred from Motomasa to Onnami.[19] That year Zeami's son Motoyoshi retired from acting to serve as a Buddhist priest.[25] That same year Motomasa died; it has been speculated that he was murdered.[19] Though he had lost political favor, Zeami continued to write prolifically.[39]

Onnami inherited the leadership of Zeami's Kanze school.[36] The appointment was made by the Shogunate, although the troupes were traditionally hereditary.[25] Zeami initially opposed Onnami's leadership of the troupe, but he eventually acquiesced.[36] Zeami believed that his line had died with Motomasa, but Onnami felt that he continued the line.[39] Zeami gave his completed works to Konparu Zenchiku, rather than to Onnami.[39]

Sado Island

In 1434, Zeami was exiled to Sado Island.[19] He completed his last recorded work two years later, providing a detailed first-person account of his exile.[40] In the account he conveys a stoic attitude toward his misfortunes.[41] Little is known about the end of his life, but it was traditionally believed that he was pardoned and return to the mainland before his death.[25] Zeami died in 1443 and was buried in Yamato. His wife died a short time later.[42]

Legacy

Zeami is known as the foremost writer of Noh and the artist who brought it to its classical epitome.[4] Scholars attribute roughly 50 plays to him, many of which have been translated into European languages. The contemporary versions of his plays are sometimes simplified. Some of his plays are no longer extant, and roughly 16 exist only in the form of rare manuscripts.[43]

There are few extant biographical documents of Zeami, the lack of solid information about his life has led to a significant amount of speculation.[4] Some common themes in the speculation are that Zeami could have been a spy, a Ji sect priest, or a Zen master.[4]

Zeami's treatises were not widely available after his death; only the upper-class warriors were able to gain access to them. In 1908, several of the treatises were discovered at a used books store in Japan. They gained wider circulation after this discovery but a complete set was not published until 1940.[44] Zeami's plays have been continually performed in Japan since they were first written.[29]

A crater on the planet Mercury was named after Zeami in 1976.[45]

References

- Louis Crompton (2003). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 424. ISBN 9780674011977.

- Hare 1996, p. 14

- Hare 1996, p. 15

- Hare 1996, p. 12

- Hare 1996, p. 16

- Hare 1996, p. 18

- Rimer 1984, p. xviii

- Hare 1996, p. 13

- Wilson 2006, p. 43

- Hare 1996, p. 17

- Hare 1996, p. 11

- Hare 1996, p. 21

- Cohen, Robert (2020). "Chapter 7: Theatre Traditions". Theatre: Brief Edition. Donovan Sherman (Twelfth ed.). New York, NY. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-260-05738-6. OCLC 1073038874.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hare 1996, p. 19

- Wilson 2006, p. 153

- Wilson 2006, p. 18

- Hare 1996, p. 30

- Hare 1996, p. 31

- Hare 1996, p. 32

- Wilson 2006, p. 45

- Hare 1996, p. 22

- Hare 1996, p. 23

- Hare 1996, p. 25

- Hare 1996, p. 26

- Rimer 1984, p. xix

- Hare 1996, p. 28

- Rath, Eric C. (2003). "Remembering Zeami: The Kanze School and Its Patriarch". Asian Theatre Journal. 20 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1353/atj.2003.0027. hdl:1808/9963. ISSN 1527-2109. S2CID 55033358.

- Tyler 1992, plays introduction

- Quinn 2005, p. 1.

- Kenklies 2018

- Rimer 1984, p. xvii

- Wilson 2006, p. 15

- Rimer 1984, p. xx

- Hare 1996, p. 29

- Hare 1996, p. 33

- Hare 1996, p. 35

- Wilson 2006, p. 46

- Hare 1996, p. 34-35

- Hare 1996, p. 36

- Hare 1996, p. 37

- Wilson 2006, p. 47

- Hare 1996, p. 38

- Rimer 1984, p. xxvii.

- Wilson 2006, p. 49.

- "Zeami". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

Bibliography

- Hare, Thomas Blenman (1996), Zeami's Style: The Noh Plays of Zeami Motokiyo, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-2677-1

- Kenklies, Karsten (2018), The eternal flower of the child: the recognition of childhood in Zeami's educational theory of Noh theatre. Educational Philosophy and Theory, E-pub ahead of print (PDF), doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1533463, S2CID 149911307

- Quinn, Shelley Fenno (2005), Developing Zeami: the Noh actor's attunement in practice, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1827-2

- Rimer, J. Thomas; Yamazaki, Masakazu (1984), On the art of the nō drama: the major treatises of Zeami, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-10154-5

- Tyler, Royall, Japanese Nō Dramas. (1992) London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0140445398.

- Wilson, William Scott (2006), The flowering spirit: classic teachings on the art of Nō, Kodansha International, ISBN 978-4-7700-2499-2