Württemberg Central Railway

The Central Railway (German: Zentralbahn or Centralbahn) was the first phase of the Württemberg railways. It was built between 1844 and 1846 by the Royal Württemberg State Railways (Königlich Württembergischen Staats-Eisenbahnen) and consisted of two branches, running from Stuttgart to Ludwigsburg in the north and from Stuttgart to Esslingen in the east.

| Central Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Rosenstein Castle with the old Rosenstein Tunnel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | Zentralbahn/Centralbahn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Baden-Württemberg, Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minimum radius | 373 m (1,224 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum incline | 1% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The term Zentralbahn did not last long, as the two branches were soon extended to Heilbronn and Ulm, and were then known as the Nordbahn (Northern Railway) and the Ostbahn (Eastern Railway) or Filsbahn (Fils Valley Railway). The Ludwigsburg–Stuttgart–Esslingen section as a whole was still of great importance, since it continued to be the core of the network and was the busiest section of the Württemberg railways and it also served the largest metropolitan area in the country. For these reasons, it has undergone many changes and enhancements over time.

Route

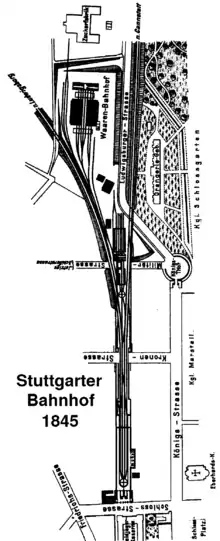

The two branches began at Zentralbahnhof (central station), which was a terminal station and was located south of the current Stuttgart Hauptbahnhof (main station) on Schlossstraße.

Both lines ran initially to the northeast. The northern branch, once it had gained altitude, curved to the left past the former cavalry barracks (now in the station track field) and then took another curve towards the suburb of Prag. This line left the Stuttgart basin by the first Prag Tunnel, which was originally 828-metre long. It passed through Feuerbach and Zuffenhausen, where it left the valley of the Feuerbach, then through Kornwestheim and originally ended in Ludwigsburg.

The eastern line ran along on the northwest side of the palace garden (Schlossgarten) to the Neckar valley. The line ran under Rosenstein Park through the Rosenstein Tunnel, which is located directly under the Rosenstein Castle. Then the line crossed the Neckar over the Rosenstein Bridge, reaching Cannstatt. Running on the right (northern) bank of the Neckar it ran to Esslingen via Untertürkheim, Obertürkheim and Mettingen.

This route no longer matches in all details the current route. The most significant changes over the years affect, apart from the vast expansion of the facilities, the location of the main Stuttgart station, the route of the Northern Railway between Stuttgart Central Station and Stuttgart North station, the position of the Rosenstein tunnels and the Neckar Viaduct.

Construction history

The Central Railway was never intended as an isolated railway line, but as the first phase of the Württemberg main line network that crossed the entire country and would connect Heilbronn and Bruchsal on the one hand with Ulm and Constance on the other. However, the section in the Württemberg heartland, had considerable intrinsic importance, especially for transport to and from Stuttgart, which suggested that construction should begin there. The route was difficult because of the geography and had to take into account both to the needs of the entire network as well as on those of Stuttgart, but a successful route was found after lengthy consideration of a variety of plans.

Geographical conditions

Stuttgart city centre is located in the valley of the Nesenbach at an altitude of about 250 metres. The valley is surrounded on three sides by hills, which rise to 200 metres above Stuttgart and fall only slightly to the northwest, where there is a low pass called the Pragsattel ("Prag saddle", 306 m). In the northeast, the valley opens up to the Neckar, which lies about 3.5 km from the Stuttgart centre. The geographical location of Stuttgart is often called a Talkessel (basin).

The population of Stuttgart had doubled to 40,000 between 1800 and 1840 and it was the largest city and the economic centre of Württemberg. The city, however, had spread primarily to the southwest (i.e. inside the basin) where the valley was relatively wide, in the north, there was discontinuous development only as far as Schillerstraße (which is now the location of Stuttgart Central Station) and along the Neckar road (Neckarstraße, part of which is now called Konrad Adenauer-Strasse). The palace gardens also prevented the growth of the city to the north; these ran from today's old town in a 200-metre-wide strip to the Neckar, where the output of the valley is again narrowed by the hills of Rosenstein (which is topped by Rosenstein Castle) and Berg. Further upstream and downstream the Neckar runs through a narrow, deep valley. Opposite the confluence of the Nesenbach with the Neckar is Cannstatt (called Bad Cannstatt since 1933). With 5,500 inhabitants, Cannstatt was much smaller than Stuttgart in 1840, but it had always been an important transport hub, as it was on an ancient trade route from the Rhine valley to the Danube (near Ulm) and the Neckar River was navigable downstream from here.

Before the invention of modern transport, Stuttgart was rarely described as having a poor location for transport purposes, which was not a principle of urban settlement normally taken into account at the time. Once the railway had been invented, its location meant that Stuttgart could not be on the direct through railway between the eastern and western borders, indeed access into the basin, except from the northeast was a problem, so that for a time Stuttgart could only be connected by a branch line, despite its economic importance and potential for generating traffic. The fact that the city barely extended towards the Neckar meant, at least, that a direct link to the city centre could be built.

Already the construction of the first railway in Württemberg was beset with difficulties that other comparable countries were spared at the time. The required levelling work, tunnels and bridges also made the construction comparatively expensive. Around 1835 the planning of railway networks was still in its infancy and it continued to develop during its planning, so that considerable uncertainty existed regarding the applicable construction parameters, such as acceptable curve radii and gradients. The ability of the economically weak Württemberg railway network to continue to extend its operations ultimately proved to be decisive for the country.

The first steps towards construction (1830–36)

The first concrete suggestion of a railway line in the Stuttgart area was made by a commission that had been formed in 1830 on the orders of King William I. This had been commissioned to investigate the building of a connection between the Rhine and Danube using canals or railways. In its interim report of 1833, it came to the conclusion that the building of railways would be appropriate and that a link between Stuttgart and Cannstatt would be useful.

The following activities are related to the continuing efforts to create a nationwide network. In 1835/36 private railway companies were formed in Stuttgart and Ulm to build a connection between the two cities. In this context, Valentin Schübler advanced a proposal for lines from Stuttgart to Heilbronn and Ulm in the Wochenblatt newspaper, which was published by the Cotta publishing house of Stuttgart. Under this proposal, the northern railway would run from a station at Seewiesen (the current location of the University of Stuttgart) to Prag, which it would pass under through a tunnel, and via Korntal to the Glems valley. The eastern railway would run from a railway station on the Neckarstraße to the east of the palace gardens by Berg and be connected to the northern railway by a one kilometre-long tunnel under the city. This proposal was not followed up, but it already contained the idea of a tunnel under Prag, which was picked up again years later.

The private railway companies were quickly dissolved when the original cost estimates proved to have been too optimistic, but stimulated further government planning. In 1836, the Interior Ministry instructed Baron Carl von Seeger (Technical Council of the Interior) and the Ulm District architect, Georg von Buhler to plan routes for the main lines. This was to clarify, among other things, whether the Eastern Railway, that is the connection to Ulm, should be built along the Rems, the Kocher and the Brenz or directly along the Fils and then crossing the Geislinger Steige, which was relevant to the route to be used in the Stuttgart area.

Buhler and Seeger’s plans (1836–43)

Buhler and Seeger completed their plan by 1839. This envisaged the building of the Stuttgart station on the Neckar road, with the line running to the east of the castle gardens to Berg. Under the Fils option, the eastern railway would have branched here from the northern railway. The eastern railway, as initially proposed by Buhler, would have continued on the left (southwest) bank of the Neckar towards Plochingen. Seeger planned the northern railway to cross the Neckar between Berg and Cannstatt. After Cannstatt it would then have switched back to the left (west) bank of the Neckar and turned left before Hoheneck to reach Ludwigsburg at the lower gate (Unteren Tor), that is north of the town centre. Under the Rems option, it would have had a junction with the Eastern Railway near Neckargröningen in Remseck. These plans were based on a maximum gradient of 1:200 and a maximum curve radius of 570 metres. Stuttgart, Cannstatt and Berg were possible locations for the central station on this route.

Upon submission of the plans the matter at first rested, partly because Seeger had retired from the service. Until 1842, there was little activity in the matter. The Austrian expert Negrelli, who was commissioned by the government, positively assessed the current plans, but realised at the same time that because of the progress of railway technology it was now possible to operate on steeper gradients and less costly infrastructure was needed. During 1842/43 the government as well as a parliamentary commission then laid down the following key elements for the works:

- Construction of the central station in Stuttgart, because most services would begin or end there;

- Favouring a line along the Fils rather than the Rems because it was direct and the through route in the case of the Rems route would run too far to the north of Stuttgart;

- Construction of the first section between Ludwigsburg, Stuttgart and Esslingen, since considerable local traffic was expected.

This last point laid the foundation stone for the construction of the Central Railway. The discussions led to the adoption of the Railway Act of 18 April 1843, which ordered the construction of the main lines. In addition, a railway commission was set up to ensure the implementation of the law and which would complete the planning of the construction of the tracks and carry out the construction. An engineer, Carl Etzel, who had already shown his abilities in railway construction, was called in to apply the experience that had gained with the construction of railways in France. Furthermore, the English engineering professor Charles Vignoles was appointed as a consultant to make a further review of the current plans as comments made by Negrelli on possible improvements raised doubts about their accuracy.

Work of the Railway Commission from 1843

The plans also met with great interest from the public. Among the many writings that were written by private individuals on the project, that of Johannes Mährlen, professor of the Polytechnic University in Stuttgart is notable. He made topographic surveys to compare different options in 1843 at his own expense. He found was most appropriate proposal was one that included elements from Schübler's proposal of 1836: a railway station on the Seewiesen, north of the old station, and a connection to Ludwigsburg through a tunnel under Prag. The novelty of this proposal was that the line from this station would go to Cannstatt to the west of the palace gardens. Moreover, this line went around the Rosenstein hill, crossed the Neckar and ran on the right (northeastern) bank of the Neckar to Esslingen. This suggestion also raised official interest, especially since King William was opposed to a railway station on the Neckar road, near the royal facilities. This proposal also gave more direct access to Ludwigsburg and allowed further development on the Neckar road.

When Etzel and Vignoles began their work, they found Buhler designs unsuitable. Etzel began to prepare new plans based on Mährlen's proposals and Vignoles recommended that they be accepted for execution. Pending final approval of the plans on 12 July 1844, Etzel made just two changes: first, it should not bypass the Rosenstein, but pass under it by a tunnel directly below the castle, this would allow Cannstatt station be placed closer to the town. Secondly, the station would not be at Seewiesen, but instead it would be established within the existing buildings in the so-called Schloßstraßenquadrat (castle streets square) (current perimeter: Bolzstraße, Friedrichstraße, Kronenstraße and Königstraße), thus enabling shorter routes to the station. Both proposals were not without controversy because existing houses would have to be demolished and it was feared that the Rosenstein tunnel would threaten the castle. The cramped location of the station, which left little room for expansion, was also criticized. Etzel gained approval for his ideas with a positive opinion from the Austrian engineer Ludwig Klein and the support of King William.

Construction of the Central Railway

On 26 June 1844, construction began on the most difficult part of the route, the Prag tunnel. In the first phase the Cannstatt–Untertürkheim section was completed, where three weeks later after the first test run on 3 October 1845, the regular operations were commenced. The extensions to Obertürkheim and Esslingen were opened shortly afterwards, on 7 and 20 November. The opening of the remaining sections was delayed because the necessary tunnels were not finished. 20 workers lost their lives during a tunnel collapse in the Prag tunnel. Also an unforeseen delay occurred when there was a water and mud intrusion into the Rosenstein tunnel had to be fixed; this was caused by the permeable basins around the castle. The Rosenstein tunnel was completed on 4 July 1846. On 26 September, a locomotive entered the Stuttgart station for the first time and, on 15 October, operations commenced on the entire Ludwigsburg–Esslingen route.

The standard gauge railway initially only had two tracks between Stuttgart and Cannstatt, but provision had been made for the later duplication of other sections, including the acquisition of land. The revised plans had a maximum gradient of 1:105 and minimum curve radius of 456 metres. The state assembly had granted 3.8 million guilders for the construction. (By comparison, the total annual budget for the financial years 1836–39 had amounted to 9.3 million guilders.)

The first timetable for the opening day of the Central Railway had four pairs of trains from Stuttgart to Ludwigsburg and Esslingen, in addition another four pairs of trains ran between Stuttgart and Cannstatt. Initially, only passenger services operated (with an average of 200 passengers per train); in 1847 the freight operations were introduced, although the space for Stuttgart freight station had already been prepared in 1845. This was located just north of the present station between the tracks of the Northern and Eastern Railways. It was connected to the tracks only from the direction of the passenger station.

Later developments

Further expansion of the network

In the following years the Württemberg railway network rapidly expanded. In 1850, railways reached Heilbronn and Friedrichshafen; in 1854, there were rail connections to Württemberg's two main neighbours, Baden and Bavaria. From 1859 there were further domestic lines that branched off from the main lines, the most important for Stuttgart was the Upper Neckar Railway from 1859, the Rems Railway from 1861, the Württemberg Black Forest Railway in 1868 and the Gäu Railway (Stuttgart–Freudenstadt) 1879. Each of these line openings extended the catchment area of Stuttgart, this and the general increase in passenger and freight traffic made sure that traffic to the Stuttgart station continued to increase. For this reason, the remaining portions of the Central Railway were duplicated between 1858 and 1861.

Upgrades in the 1860s/70s

In the 1860s, the State Railways carried its first major renovation of the Stuttgart rail network: Stuttgart station was replaced by a new building in 1867/68 and expanded from four to eight tracks and its subgrade was slightly raised, causing the slope of the Cannstatt line to be increased to 1:100. In addition, the freight yard was built and a rail link was built between the Northern and Eastern Railway to the north of the freight yard, so that trains coming from Cannstatt could more easily reach the freight yard; this track included the 48 metre-long Galgensteig tunnel. In the 1870s the expansion of the facilities of the freight yard continued, filling the angle between Bahnhofstraße (now Heilbronnerstraße) and Wolframstraße.

Relief from through traffic in the 1890s

Around 1890, the station facilities in Stuttgart were overloaded again. To remedy the situation, through freight traffic was moved out of the city. This involved the building of the freight bypass railway between Untertürkheim and Kornwestheim and marshalling yards at both ends. This required the railway tracks at Untertürkheim to be moved closer to the Neckar. Another marshalling yard was built at the junction of the Black Forest Railway with the Northern Railway at Stuttgart North station (then called Prag station), which could be used by traffic to and from the Black Forest Railway. A locomotive depot and a new passenger station were also built there. A residential area was built in Prag for rail workers; its street names still refer to notable figures in the history of the railways.

Renovation period 1908–1929

The measures taken in the 1890s provided only brief relief. Stuttgart had almost 180,000 inhabitants in 1900, ten years earlier, the figure had been 140,000. Therefore, new plans were already under way in 1901, this time involving a complete redesign of the rail facilities between Stuttgart and Ludwigsburg and Esslingen. The objective of the planning was the refurbishment of the Stuttgart railway facilities to the extent that there was a complete re-development of rail infrastructure in the Stuttgart basin. It was assumed that the city would grow to have a population of 300,000.

For this purpose the lines to Esslingen and Cannstatt would be upgraded to four tracks to separate local and long-distance traffic from each other. Furthermore, a decentralised structure was sought, that is the handling of freight would be taken over by stations outside the city centre. After demands that the station be transferred to Cannstatt and transformed into a through station had been rejected, two approaches to the station building were available: the upgrade of facilities in the existing station or a new station 500 metres further north at Schillerstraße. For financial reasons—the Schillerstraße concept allowed for the sale of the former railway station premises in a prime central location—the latter prevailed and it was adopted by the Parliament in 1907.

The relocation of the station to the north led to the relocation of the approach routes to Ludwigsburg and Böblingen. These were moved from the western side of the Prag settlement to its eastern side, which extended the initial section of the line and decreased its slope. An operations station was built on Rosenstein Park between the new tracks to the north and the line to Cannstatt. In 1908–10, the second double-track Prag Tunnel tube was built while the Rosenstein tunnel and the following bridge was completely rebuilt in 1914. There were also extensive expansion projects at the other stations along the route. The quadruplication of tracks in the Untertürkheim area meant that the Neckar had to be straightened. Between 1912 and 1919, a huge new marshalling yard was built west of Kornwestheim that relieved the marshalling yards at Stuttgart North station and in Untertürkheim of their duties. The opening of the Rankbach Railway in 1915 meant that the railway between Kornwestheim and North Station was relieved of freight transport.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, there were fewer workers, material and financial resources available, so the completion of the new infrastructure was delayed for years.

The completion of the new Stuttgart Central Station (Hauptbahnhof) was particularly affected. Begun in 1914, it was originally intended to go into operation in 1916–19; in fact, this happened only in stages between 1922 and 1928. In 1929, renovations were completed with the opening of the new customs building at the freight yard.

Developments after 1929

The next major change in the operation carried out was the electrification of the suburban lines between Esslingen, Stuttgart and Ludwigsburg on 15 May 1933. As early as 1 June of that year long-distance services were electrified to Ulm; electrification to Bruchsal was delayed until 1950.

Numerous air raids during World War II placed heavy burdens of operations on the track. On 22 November 1942, Stuttgart Central Station was also badly hit. As a result, operations had to be reorganised temporarily. On 21 April 1945, German troops blew up the Neckar bridge to Rosenstein Tunnel, causing traffic between Stuttgart and Cannstatt to come to a complete standstill. Operations were restored only on 13 June 1946; the reconstruction of the main station lasted until 1960.

The relocation of the Central Station to the north along with the growth of the city to the southwest had given rise to considerations from 1930 of building an underground railway into the basin to supplement the existing lines. The construction of the rail link and the commissioning of the Stuttgart S-Bahn made these plans a reality on 1 October 1978. The S-Bahn replaced the existing suburban services and included the lines between Esslingen, Ludwigsburg and Stuttgart from the beginning.

Since the late 1960s, Deutsche Bundesbahn (or, now, Deutsche Bahn) have planned the construction of new lines, which would allow high-speed passenger services to be separated from other traffic. In this context, the opening of the Mannheim–Stuttgart high-speed railway in 1991 required the deviation of the main line between Zuffenhausen and Kornwestheim, but the line to Ludwigsburg was not completely relieved of long-distance traffic. Other new works are planned as part of the Stuttgart 21 project.

Relics

The location of the old Central Station south of the current station can be seen in two long, straight roads in the central city. Stephanstraße is at the location of the first station in Stuttgart and at the eastern half of the second station on the same site, Lautenschlagerstraße is at the location of the western half of the second station. Both streets were opened and named in 1925, after the building of the current Central Station. Parts of the central portal of the second station are now used as the entrance of a cinema.

The Central Station's track field formerly extended to the corner of Heilbronnerstraße (until 1936: Bahnhofstraße) and Wolframstraße, this has been partially demolished. Nordbahnhofstrasse runs to the north along the path formerly used by the Northern Railway past the cavalry barracks.

Until the reorganisation of lines at the beginning of the 20th century, the railway ran to the west of the modern Nordbahnhofstraße. The circular boundary of Prag cemetery in the north marks the former course of the railway to the North Station and the former branch of the Gäu Railway. The Inner North Station used to be on this track on the north side of the cemetery. Only with the rebuilding the tracks were to the east was the station moved to the current location of the North Station.

The (walled-up) portal of the original Rosenstein tunnel is still visible on the side of the Neckar at Rosenstein; it is below the walkway that leads up from the pedestrian bridge over the Neckar River to the castle.

See also

References

Footnotes

- Eisenbahnatlas Deutschland [German railway atlas]. Schweers + Wall. 2017. p. 168. ISBN 978-3-89494-146-8.

Sources

- Räntzsch, Andreas M. (1987). Stuttgart und seine Eisenbahnen. Die Entwicklung des Eisenbahnwesens im Raum Stuttgart (in German). Heidenheim: Uwe Siedentop. ISBN 3-925887-03-2.

- Räntzsch, Andreas M. (2005). Die Einbeziehung Stuttgarts in das moderne Verkehrswesen durch den Bau der Eisenbahn (volume 1 and 2) (in German). Hamburg: Dr. Kovač. ISBN 3-8300-1958-0., (Dissertation, University of Stuttgart, 2005)

- von Morlok, Georg (1986) [1890]. Die Königlich Württembergischen Staatseisenbahnen: Rückschau auf deren Erbauung während der Jahre 1835–1889 unter Berücksichtigung ihrer geschichtlichen, technischen und finanziellen Momente und Ergebnisse (in German) (reprint ed.). Heidenheim: Siedentop. ISBN 3-924305-01-3.