Amphion and Zethus

Amphion (/æmˈfaɪ.ɒn/ (Ancient Greek: Ἀμφίων, romanized: Amphīōn)) and Zethus (/ˈziːθəs/; Ζῆθος Zēthos) were, in ancient Greek mythology, the twin sons of Zeus (or Theobus)[2] by Antiope. They are important characters in one of the two founding myths of the city of Thebes, because they constructed the city's walls. Zethus or Amphion had a daughter who was called Neis (Νηίς), the Neitian gate at Thebes was believed to have derived its name from her.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Mythology

Childhood

Amphion and Zethus were the sons of Antiope, who fled in shame to Sicyon after Zeus raped her, and married King Epopeus there. However, either Nycteus or Lycus attacked Sicyon in order to carry her back to Thebes and punish her. On the way back, she gave birth to the twins and was forced to expose them on Mount Cithaeron. Lycus gave her to his wife, Dirce, who treated her very cruelly for many years.[4]

Antiope eventually escaped and found her sons living near Mount Cithaeron. After they were convinced that she was their mother, they killed Dirce by tying her to the horns of a bull, gathered an army, and conquered Thebes, becoming its joint rulers.[4] They also either killed Lycus or forced him to give up his throne.[5]

Rule of Thebes

Amphion became a great singer and musician after his lover Hermes taught him to play and gave him a golden lyre. Zethus became a hunter and herdsman, with a great interest in cattle breeding. As Zethus was associated with agriculture and the hunt, his attribute was the hunting dog, while Amphion’s - the lyre.[5] Amphion and Zethus built fortifications of Thebes.[5] They built the walls around the Cadmea, the citadel of Thebes at the command of Apollo.[6] While Zethus struggled to carry his stones, Amphion played his lyre and his stones followed after him and gently glided into place.[7]

Amphion married Niobe, the daughter of Tantalus, the Lydian king. Because of this, he learned to play his lyre in the Lydian mode and added three strings to it.[8] Zethus married Thebe, after whom the city of Thebes was named. Otherwise, the kingdom was named in honour of their supposed father Theobus.[9]

Later misfortunes

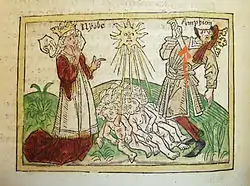

Amphion's wife Niobe had many children, but had become arrogant and because of this she insulted the goddess Leto, who had only two children, Artemis and Apollo. Leto's children killed Niobe's children in retaliation (see Niobe). It’s Niobe’s overweening pride in her children, offending Apollo and Artemis, brought about her children’s deaths.[5] In Ovid, Amphion commits suicide out of grief; according to Telesilla, Artemis and Apollo murder him along with his children. Hyginus, however, writes that in his madness he tried to attack the temple of Apollo, and was killed by the god's arrows.[10]

Zethus had only one son, who died through a mistake of his mother Thebe, causing Zethus to kill himself.[7] In the Odyssey, however, Zethus's wife is called Aëdon, a daughter of Pandareus in book 19, who killed her son Itylus in a fit of madness and became a nightingale.[11] Later authors would clarify that Aëdon tried to kill Niobe and Amphion's firstborn Amaleus out of jealousy that Niobe had borne many children, while she and Zethus only had one.[12][13] However in the dark of the night, Aëdon by mistake killed Itylus, and in her mourning she was transformed into a nightingale by Zeus[14][15] when Zethus began to chase her down in rage for murdering their son.[16] Alternatively, Aëdon was afraid that Zethus (here, mistakenly perhaps, spelled Zetes) was having an affair with a nymph, and that Itylus was assisting his father in his infidelity, so she killed him.[17][18]

After the deaths of Amphion and Zethus, Laius returned to Thebes and became king.

Compare with Castor and Polydeuces (the Dioscuri) of Greece, and with Romulus and Remus of Rome.

Family tree

| Royal house of Thebes family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Amphion

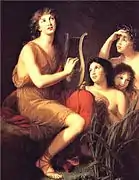

Amphion, son of Zeus and Antiope, and twin brother of Zethus

Amphion, son of Zeus and Antiope, and twin brother of Zethus Amphion by NathanJacquin (November 16, 2015)

Amphion by NathanJacquin (November 16, 2015).jpg.webp) Amphion

Amphion Mercury and Amphion by Jean Vignaud (1819)

Mercury and Amphion by Jean Vignaud (1819) Amphion by Krauss, Johann Ulrich (ca. 1690)

Amphion by Krauss, Johann Ulrich (ca. 1690)

Amphion and Zethus

.jpg.webp) The Farnese Bull depicting the punishment of Dirke by Amphion and Zethos

The Farnese Bull depicting the punishment of Dirke by Amphion and Zethos_-_Napoli_MAN_9042_-_01.jpg.webp) Dirce being tied to a bull by Amphion as Zethus looks on; Antiope tries to stop her son's hand. (fresco, 1st century AD)

Dirce being tied to a bull by Amphion as Zethus looks on; Antiope tries to stop her son's hand. (fresco, 1st century AD)_(14760065506).jpg.webp) The Famese Bull

The Famese Bull Amphion and Zethus

Amphion and Zethus Julius Troschel, Amphion and Zethus (1840-1850), Neue Pinakothek.

Julius Troschel, Amphion and Zethus (1840-1850), Neue Pinakothek.

See also

Notes

- This Antiochus has not been identified. Carvalho Abrantes, Miguel (30 April 2017). "2.16 Antiochus". Explicit Sources of Tzetzes' Chiliades (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1545584620. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- According to other writers and to Antiochus [1] as cited in John Tzetzes. Chiliades, 1.13 line 319

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Neis

- Apollodorus, 3.5.5

- Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 58, at Google Books

- Hyginus, Fabulae 9

- Tripp, Edward. Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1970, p. 44. Original, less elaborate, account in Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio 6.20.18

- Tripp, Edward. Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1970, p. 43

- Tzetzes, Chiliades 1.13 line 322

- Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, p. 539

- Homer, Odyssey Trans. Richmond Lattimore. New York: Harper Collins, 1967, p. 295

- Pimentel & Simoes Rodrigues 2019, p. 201.

- Fowler 2000, p. 341.

- Eustathius of Thessalonica, On Homer's Odyssey 19.710

- Hansen 2002, p. 303.

- Scholiast on the Odyssey 19.518

- Photios I of Constantinople, Myriobiblon Helladius Chrestomathia

- Wright, Rosemary M. "A Dictionary of Classical Mythology: Summary of Transformations". mythandreligion.upatras.gr. University of Patras. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

References

- Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Fowler, Robert Louis (2000). Early Greek Mythography: Texts. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814740-6.

- Hansen, William F. (2002). Ariadne's Thread: A Guide to International Tales Found in Classical Literature. UK, USA: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3670-2.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. ISBN 978-0674995611. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. ISBN 0-674-99328-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pimentel, Maria Cristina; Simoes Rodrigues, Nuno (March 20, 2019). Violence in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Bristol, USA: Peeters, ISD LLC. ISBN 978-90-429-3602-7.

- Tzetzes, John, Book of Histories, Book I translated by Ana Untila from the original Greek of T. Kiessling's edition of 1826. Online version at theio.com

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Amphion and Zethus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Michels, Johanna Astrid (2023). "Theban Myths: Amphion & Zethus and the Labdacids (III.40–47)". Agenorid Myth in the 'Bibliotheca' of Pseudo-Apollodorus: A Philological Commentary of Bibl. III.1-56 and a Study into the Composition and Organization of the Handbook. Beiträge zur Altertumskunde. Vol. 42. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 550–642. doi:10.1515/9783110610529-012. ISBN 9783110610529.