Zia people (New Mexico)

The Zia /ˈziːə/ or Tsʾíiyʾamʾé are an indigenous nation centered at Zia Pueblo (Tsi'ya), a Native American reservation in the U.S. state of New Mexico. The Zia are known for their pottery and use of the sun symbol. They are one of the Keres Pueblo peoples and speak the Eastern Keres language.[3]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 850[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

( | |

| Languages | |

| Keresan, English, Spanish | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pueblo community | |

PUEBLO OF ZIA 2009 GOVERNOR IVAN R. PINO[1][2] |

History

Archaeologists believe that the Keresan-speaking residents of Zia are descendants of the Ancestral Puebloan people of the Four Corners region, who migrated to the Jemez River Valley sometime in the 13th century.[4] The Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo first encountered the Zia in 1583, when he noted that the largest pueblo was the one the natives called Tsiya, which the Spanish later renamed to Zia.

Spanish settlers and their religious orders slowly took control of the region and outlawed traditional Zia religious ceremonies. The first missionary was assigned to the Zia in 1598 by Don Juan De Oñate, and by 1613, a church and convent had been built by tribal members.[1] Tensions between the Spanish and Zia continued to build until 1680, when a regional uprising led by Popé, a Tewa religious leader, overthrew the Spanish regime. The uprising was successful and the Spanish were forced to flee south. The Pueblo Indians acquired horses from the Spanish, thus allowing the further spread of horses to the Plains tribes.[5]

The Spanish did not return for another 9 years, laying siege to Zia Pueblo in 1689. Soldiers led by Governor Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate sacked the pueblo, killing 600 people and taking 70 Zia Indians captive.[6] Three years later, the Spanish had crushed any Pueblo resistance and convinced the Zia people and their leader, Antonio Malacate, to return to their homes, but fighting and disease had taken their toll, with only about 120 people left living in Zia in 1892.[7]

Living and culture

Farming techniques

Because of the arid climate of the land where they live, the Zia had to adapt to the way of life in a way best suited for the desert. Since they were home dwellers instead of nomads, farming was essential to their supply of food.[3]

In New Mexico, rain was scarce during certain parts of the year, so new techniques of farming were developed (such as dry farming and crop rotation) The Zia would plant seeds in a fertile piece of land close to a river or stream. They would then dig paths to the fields from the stream, and thus the water flowed from the stream to water the crops. By strategically placing rocks in the paths, they controlled the flow of water to their crops.

In the more elevated regions, men planted seeds in a patch on a sunny slope. When it rained, the rainwater ran down the slope to water the crops. Another method was digging trenches, used as cisterns, to collect the rain. Women would go to these trenches with clay pottery to collect water for watering the fields.

Crops

Zia farming produced a wide array of crops, but the most important of these were corn, beans, and squash, nicknamed the "three sisters". These crops were planted in shared or common ground, to which everyone contributed. They were the staple of Zia and Pueblo diets. Corn was the most important of all. While some was eaten fresh, most was stored away in pots and cellars for the winter and droughts. When some of the corn dried, it was turned into flour and bread by the women. They sat outside at grinding stones, singing religious songs while rubbing stones against the corn, producing flour. They sang, because they considered the corn to be sacred.[8]

Once the flour was done, it was mixed with water to make dough. The dough was widened to round, flat sheets and placed on hot rocks over a fire. When done baking, a tortilla was produced; it was the most important staple available to them.

Other minor crops were grown in personal, individual gardens, such as peppers, onions, chiles, and tobacco. New Mexico is well known for its spicy chiles that originated among tribes like this.[9]

Meat sources

The Zia were primarily vegetarians, but they ate meat when it was available. Small hunting parties of men and teenaged boys were sent to hunt for small game such as rabbits, gophers, and squirrels. They also hunted large game such as deer, antelope, and mountain lions. When the spring season came, special groups would go close to the Great Plains to hunt for bison.[9]

Housing

The natives of the southwestern United States, including the Zia, were known for their "pueblo homes" made of adobe. These were built like an apartment complex with a huge box base, smaller box on top, and an even smaller one on top of that. This architecture created different floors for storing different items and for families. Until recently, no doors were located on the bottom floor, so the only way to access the building was by ladders made from logs. One ladder would reach from the ground to the patio (second floor) and another led through an opening through a roof and down onto the first floor.[10] Other ladders led to higher floors. At night, ladders would be taken inside for protection, so no outsider could come in without permission.[8]

Adobe houses are made from the natural resources of the nearby desert. Adobe, the building-block, is made by mixing clay, sand, water and organic materials such as sticks, straw, and dung. The mixture is formed into blocks and left to dry. Meanwhile, a hole is dug where the new building is to be constructed and supporting poles are planted firmly in the ground to make a frame. When the blocks of adobe are dry and hard, they are laid around the building and bonded by wet clay, used as a cement. Every year, a new coat of adobe mixture/clay is added to the walls for maintenance.

Religious customs

Kachinas

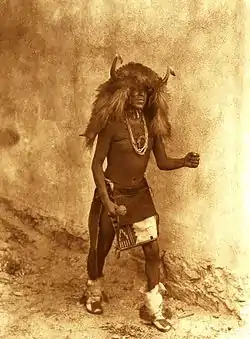

The Zia, like the other Pueblos, believe in different spirits called kachinas. These are thought to be ancestral spirits that live among their people. The spirits got offended when people did not pay them attention, so they fled to live in the sky. They were said to come occasionally and bring rain and clouds. Over 300 kachinas are present in the worship, and the Zia held religious festivals and ceremonies in which they ask them to bring rain and make their crops grow. They used drums and rattles in the dances during the ceremonies. Religious men dressed as the kachinas come down from the mountains and dance among the people during the festival. After three days, they go back up.

Art

Pottery is a widely recognized art form and an important part of daily life in Zia Pueblo. Due to the fine quality of the craftsmanship and the poor agricultural land where the pueblo is located, pottery has been historically important for trade. At the end of the 19th century, an estimated 25 or fewer women were making the entirety of the pottery for the village.[11]

Zia pottery is unique in that it is tempered with basalt, a hard volcanic rock.[11] Pots are made by mixing clay and ground basalt with water and then coiling ropes of this mixture into specific shapes.[12] Once they dry out, the pots are painted with nature and religious symbols. They then sit for about a week before they are fired in the kiln, in which cattle dung is usually used for fuel. Common motifs include geometric designs, plants, and animals, and are often on a white or red background.[13][14]

Most pottery is made by women.[14] One of the most well-known Zia potters is Elizabeth Toya Medina (originally of Jemez).[12]

Sun symbol

The Zia regard the Sun as sacred. Their solar symbol, a red circle with groups of rays pointing in four directions, is painted on ceremonial vases, drawn on the ground around campfires, and used to introduce newborns to the Sun. Four is the sacred number of the Zia and can be found repeated in the four points radiating from the circle. The number four is embodied in:

- the four points of the compass (north, south, east, and west)

- the four seasons of the year (spring, summer, autumn, and winter)

- the four periods of each day (morning, noon, evening, and night)

- the four seasons of life (childhood, youth, middle years, and old age)

- the four sacred obligations one must develop (a strong body, a clear mind, a pure spirit, and a devotion to the welfare of others), according to Zia belief

The symbol is representative of the much broader Puebloan, affiliated Hispano communities, and New Mexican culture, for example it is featured on the flag of New Mexico, in the design of the New Mexico State Capitol, on New Mexico's State Quarter entry, numerous city flags including Albuquerque and Roswell, and the state highway marker. The Zia tribe does not hold a trademark to the symbol because, under U.S. federal law, it has ubiquitous regional representation. The state government of New Mexico guides people to educational resources on the appropriate use of the sun symbol at Zia Pueblo and at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, including information on receiving permission for commercial use and asking for the symbol be used respectfully in civil use.[15][16][17] The symbol was featured on the flag of Madison, Wisconsin from 1962 through 2018, when concerns about cultural appropriation of the Zia, Puebloan, and New Mexican symbol led the city to remove it.[18] A resolution was passed in 2014, by the National Congress of American Indians to recognize the Zia pueblo’s right to the symbol.

Notable Zia people

- Marcelina Herrera, painter

- Elizabeth Toya Medina, potter (originally of Jemez)

References

- "Welcome to Pueblo of Zia". zia.com. 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- "2009 PUEBLO GOVERNORS AND TRIBAL OFFICIALS". 19pueblos.org. 2009. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- "Zia Pueblo". indianpueblo. 2009. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- pg 189 - David Pike (2004). Roadside New Mexico (August 15, 2004 ed.). University of New Mexico Press. p. 440. ISBN 0-8263-3118-1.

- pg 32 - Phillip M. White (2006). American Indian chronology (August 30, 2006 ed.). Greenwood Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-313-33820-5.

- pg 33 - Margaret Szasz (2001). Between Indian and White Worlds (September 2001 ed.). University of Oklahoma Press. p. 386. ISBN 0-8061-3385-6.

- Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (2009). "Bartolome de Ojeda". New Mexico Office of the State Historian. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- "Zia Pueblo". AAANativeArts.com. 2009. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- "Pueblo". mce. 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- "Information about the Pueblo Indians". essortment. 2009. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- Trimble, Stephen (1987). Talking with the clay : the art of Pueblo pottery (1st ed.). Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press. ISBN 0933452152. OCLC 15082081.

- Schaaf, Gregory (2002). Southern Pueblo Pottery: 2,000 Artist Biographies. American Indian Art Series. Vol. 4. Santa Fe, New Mexico: CIAC Press. p. 203.

- "Zia Pueblo". New Mexico Tourism Department. 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- Harlow, Francis H. (2003). The pottery of Zia Pueblo. Lanmon, Dwight P. (1st ed.). Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press. pp. 234–257. ISBN 1930618263. OCLC 52057686.

- McSherry, Erin (August 30, 2014). "Report to the Indian Affairs Committee of the New Mexico Legislature: Zia Pueblo" (PDF). New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.

- Turner, Stephanie B. (2012). "The Case of the Zia: Looking Beyond Trademark Law To Protect Sacred Symbols" (PDF). Student Scholarship Papers. Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. Paper 124.

- Boswell, Alisa (April 21, 2015). "Zia Pueblo say they want symbol used respectfully". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Wroge, Logan (July 24, 2018). "Madison City Council approves modified flag design". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved April 15, 2020.