Zika virus outbreak timeline

This article primarily covers the chronology of the 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic. Flag icons denote the first announcements of confirmed cases by the respective nation-states, their first deaths (and other events such as their first reported cases of microcephaly and major public health announcements), and relevant sessions and announcements of the World Health Organization (WHO), and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), as well as relevant virological, epidemiological, and entomological studies.

Timeline

The date of the first confirmations of the disease or any event in a country may be before or after the date of the events in local time because of the International Dateline.

1947–1983

![]() Uganda

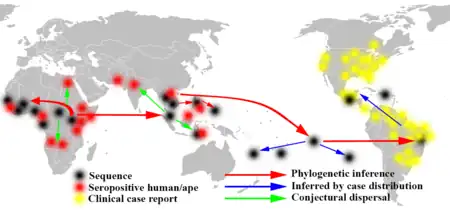

The Zika virus is first isolated in 1947 in a rhesus monkey in the Zika Forest near Entebbe, Uganda, and first recovered from an Aedes africanus mosquito in 1948.[4][5] Serological evidence indicates additional human exposure and/or presence in some mosquito species between 1951 and 1981 in parts of Africa (Uganda and Tanzania having the first detection of antibody in humans, in 1952,[6] followed by isolation of the virus from a young girl in Nigeria in 1954 during an outbreak of jaundice,[7] and experimental infection in a human volunteer in 1956.[8] The virus was then found variously in Egypt, Central African Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Gabon; Between 1969 and 1983, Zika was found in equatorial Asia including India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Pakistan.[9] Zika is generally found in mosquitoes and monkeys in a band of countries stretching across equatorial Africa)[10] and Asia (Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia).[11][12][13] The first confirmed case of Zika fever in a human occurs in Uganda during 1964 in a field researcher, who experiences a mild, non-itchy rash.[4]

Uganda

The Zika virus is first isolated in 1947 in a rhesus monkey in the Zika Forest near Entebbe, Uganda, and first recovered from an Aedes africanus mosquito in 1948.[4][5] Serological evidence indicates additional human exposure and/or presence in some mosquito species between 1951 and 1981 in parts of Africa (Uganda and Tanzania having the first detection of antibody in humans, in 1952,[6] followed by isolation of the virus from a young girl in Nigeria in 1954 during an outbreak of jaundice,[7] and experimental infection in a human volunteer in 1956.[8] The virus was then found variously in Egypt, Central African Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Gabon; Between 1969 and 1983, Zika was found in equatorial Asia including India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Pakistan.[9] Zika is generally found in mosquitoes and monkeys in a band of countries stretching across equatorial Africa)[10] and Asia (Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia).[11][12][13] The first confirmed case of Zika fever in a human occurs in Uganda during 1964 in a field researcher, who experiences a mild, non-itchy rash.[4]

2007

![]() Federated States of Micronesia

The first major outbreak is identified outside of Africa and Asia, on Yap Island. Previously only 14 cases of Zika fever had been documented since the virus had first been identified in 1947.[11][14] Approximately 5,005 people, more than 70% of the population of 7,391, were infected with Zika, and generally exhibited mild symptoms; no cases of microcephaly were reported.[12]

Federated States of Micronesia

The first major outbreak is identified outside of Africa and Asia, on Yap Island. Previously only 14 cases of Zika fever had been documented since the virus had first been identified in 1947.[11][14] Approximately 5,005 people, more than 70% of the population of 7,391, were infected with Zika, and generally exhibited mild symptoms; no cases of microcephaly were reported.[12]

2008

![]() United States

The first case of sexual transmission is reported, that of a scientist who had fallen ill in Senegal who thereafter infected his wife.[4]

United States

The first case of sexual transmission is reported, that of a scientist who had fallen ill in Senegal who thereafter infected his wife.[4]

2012

Researchers identify two distinct lineages of the Zika virus, African and Asian.[4][10][15][16][17][18]

2013–2014

![]() French Polynesia

In October 2013, an independent outbreak of the Zika virus occurred in the Society, Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands of French Polynesia.[19] The outbreak abated in October 2014, with 8,723 suspected cases of Zika reported. The true number of Zika cases was estimated at more than 30,000.[20] An unusual rise in neurological syndromes is reported, including 42 cases of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS);[21] typically five cases are reported in a three-month timeframe.[22]

French Polynesia

In October 2013, an independent outbreak of the Zika virus occurred in the Society, Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands of French Polynesia.[19] The outbreak abated in October 2014, with 8,723 suspected cases of Zika reported. The true number of Zika cases was estimated at more than 30,000.[20] An unusual rise in neurological syndromes is reported, including 42 cases of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS);[21] typically five cases are reported in a three-month timeframe.[22]

![]() French Polynesia On 20 March, researchers discover that two mothers and their newborns test positive for Zika, perinatal transmission confirmed by polymerase chain reaction performed on serum collected within four days of birth during the outbreak.[4][23]

French Polynesia On 20 March, researchers discover that two mothers and their newborns test positive for Zika, perinatal transmission confirmed by polymerase chain reaction performed on serum collected within four days of birth during the outbreak.[4][23]

![]() French Polynesia On 31 March, researchers on Tahiti report that 2.8% of blood donors between November 2013 and February 2014 tested positive for the Zika virus, of which 3% were asymptomatic at the time of blood donation.[24] This indicated a potential risk of transmission of the Zika virus through blood transfusions, but there were no confirmed cases of this occurring.[25]

French Polynesia On 31 March, researchers on Tahiti report that 2.8% of blood donors between November 2013 and February 2014 tested positive for the Zika virus, of which 3% were asymptomatic at the time of blood donation.[24] This indicated a potential risk of transmission of the Zika virus through blood transfusions, but there were no confirmed cases of this occurring.[25]

![]() French Polynesia On 13 December, a patient recovering from Zika infection on Tahiti seeks treatment for bloody sperm. Zika virus is isolated from his semen, adding to the evidence that Zika can be sexually transmitted.[4][26]

French Polynesia On 13 December, a patient recovering from Zika infection on Tahiti seeks treatment for bloody sperm. Zika virus is isolated from his semen, adding to the evidence that Zika can be sexually transmitted.[4][26]

![]() Japan

In December 2013, a Japanese tourist returning to Japan was diagnosed with Zika virus infection by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases after visiting the French Polynesian island of Bora Bora, becoming the first imported case of Zika fever in Japan.[27]

Japan

In December 2013, a Japanese tourist returning to Japan was diagnosed with Zika virus infection by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases after visiting the French Polynesian island of Bora Bora, becoming the first imported case of Zika fever in Japan.[27]

![]() New Caledonia

In January 2014, indigenous cases of Zika virus infection were reported in New Caledonia.[28] The outbreak peaked in April, with the number of confirmed cases reaching 1,400 by 17 September.[21]

New Caledonia

In January 2014, indigenous cases of Zika virus infection were reported in New Caledonia.[28] The outbreak peaked in April, with the number of confirmed cases reaching 1,400 by 17 September.[21]

![]() Cook Islands

In February 2014, an outbreak of Zika started in the Cook Islands. The outbreak ended on 29 May, with 50 confirmed and 932 suspected cases of Zika virus infection.[21][29]

Cook Islands

In February 2014, an outbreak of Zika started in the Cook Islands. The outbreak ended on 29 May, with 50 confirmed and 932 suspected cases of Zika virus infection.[21][29]

![]() Easter Island

In March 2014, there were one confirmed and 40 suspected cases of Zika virus infection on Easter Island.[30]

Easter Island

In March 2014, there were one confirmed and 40 suspected cases of Zika virus infection on Easter Island.[30]

![]() Bangladesh

A human blood sample that was obtained in 2014 was confirmed to have Zika virus by Bangladesh's health ministry on 22 March 2016.[31]

Bangladesh

A human blood sample that was obtained in 2014 was confirmed to have Zika virus by Bangladesh's health ministry on 22 March 2016.[31]

February

![]() Solomon Islands

An outbreak of Zika begins on the Solomon Islands, with 302 cases reported by 3 May.[32]

Solomon Islands

An outbreak of Zika begins on the Solomon Islands, with 302 cases reported by 3 May.[32]

March

![]() Brazil On 2 March, an illness in Northeastern Brazil characterized by a skin rash is reported.[33] In 2015 alone the virus was detected in several other regions. Subsequent genetic analysis of Brazilian Zika genomes suggest that virus may have been circulating undetected for over 1 year in Brazil.[34]

Brazil On 2 March, an illness in Northeastern Brazil characterized by a skin rash is reported.[33] In 2015 alone the virus was detected in several other regions. Subsequent genetic analysis of Brazilian Zika genomes suggest that virus may have been circulating undetected for over 1 year in Brazil.[34]

April

![]() Vanuatu

On 27 April, the Vanuatu Ministry of Health reports that blood samples collected before March were confirmed to contain the Zika virus.[35]

Vanuatu

On 27 April, the Vanuatu Ministry of Health reports that blood samples collected before March were confirmed to contain the Zika virus.[35]

![]() Brazil

On 29 April, samples first test positive for the Zika virus.[10]

Brazil

On 29 April, samples first test positive for the Zika virus.[10]

May

![]() Brazil

On 15 May, the Ministry of Health reports the presence and circulation of the Zika virus in the states of Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte after testing 16 people for Zika.[36]

Brazil

On 15 May, the Ministry of Health reports the presence and circulation of the Zika virus in the states of Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte after testing 16 people for Zika.[36]

July

![]() Brazil

On 17 July, neurological disorders in newborns associated with history of infection are reported.[10]

Brazil

On 17 July, neurological disorders in newborns associated with history of infection are reported.[10]

September

![]() Brazil

A sharp increase in the number of microcephaly cases is reported. The state of Pernambuco used to register 10 cases of microcephaly annually,[37] whereas in 2015 over 140 cases were registered.[38]

Brazil

A sharp increase in the number of microcephaly cases is reported. The state of Pernambuco used to register 10 cases of microcephaly annually,[37] whereas in 2015 over 140 cases were registered.[38]

October

![]() Colombia

On 16 October, Colombia confirms, by PCR, its first autochthonous Zika cases.[39]

Colombia

On 16 October, Colombia confirms, by PCR, its first autochthonous Zika cases.[39]

![]() Colombia

27 cases of Guillain–Barré syndrome are reported in the region around Cucuta; 27,000 cases of Zika are reported nationwide.[40]

Colombia

27 cases of Guillain–Barré syndrome are reported in the region around Cucuta; 27,000 cases of Zika are reported nationwide.[40]

![]() Cape Verde

On 21 October, Cabo Verde confirms, by PCR, its first outbreak of Zika.[41]

Cape Verde

On 21 October, Cabo Verde confirms, by PCR, its first outbreak of Zika.[41]

November

![]() Suriname

On 2 November, Suriname reports its first two autochthonous cases.[42]

Suriname

On 2 November, Suriname reports its first two autochthonous cases.[42]

![]() Brazil

On 11 November, the Ministry of Health declares a national public health emergency.[37][43]

Brazil

On 11 November, the Ministry of Health declares a national public health emergency.[37][43]

![]() United Nations

On 17 November, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), under the aegis of the WHO, issues an Epidemiological Alert regarding the increase in microcephaly cases in northeastern Brazil.[37]

United Nations

On 17 November, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), under the aegis of the WHO, issues an Epidemiological Alert regarding the increase in microcephaly cases in northeastern Brazil.[37]

![]() French Polynesia

On 24 November, French Polynesian authorities announce that there had been an unusual increase in the number of cases of central nervous system malformations in fetuses and infants, including microcephaly, following the 2013–2014 outbreak.[44][45]

French Polynesia

On 24 November, French Polynesian authorities announce that there had been an unusual increase in the number of cases of central nervous system malformations in fetuses and infants, including microcephaly, following the 2013–2014 outbreak.[44][45]

![]() El Salvador

Also on 24 November, El Salvador reports its first three autochthonous cases [46]

El Salvador

Also on 24 November, El Salvador reports its first three autochthonous cases [46]

![]() Guatemala

On 26 November, Guatemala confirms, by PCR, its first autochthonous cases of Zika.[41]

Guatemala

On 26 November, Guatemala confirms, by PCR, its first autochthonous cases of Zika.[41]

![]() Mexico

Also on 26 November, Mexico reports its first three cases of Zika infection, two autochthonous and one travel related (from Columbia).[47]

Mexico

Also on 26 November, Mexico reports its first three cases of Zika infection, two autochthonous and one travel related (from Columbia).[47]

![]() Paraguay

On 27 November Paraguay reports its first autochthonous cases.[48]

Paraguay

On 27 November Paraguay reports its first autochthonous cases.[48]

![]() Venezuela

Also on 27 November, Venezuela reports its first seven cases.[49]

Venezuela

Also on 27 November, Venezuela reports its first seven cases.[49]

![]() Samoa,

Samoa, ![]() American Samoa and

American Samoa and ![]() Tonga

Local transmission of the Zika virus by mosquitoes is reported in the Polynesian islands of Samoa, American Samoa and Tonga.[50]

Tonga

Local transmission of the Zika virus by mosquitoes is reported in the Polynesian islands of Samoa, American Samoa and Tonga.[50]

December

![]() United Nations

On 1 December, PAHO releases a report noting the possible connection between the Zika virus and the rise in neurological syndromes. Three deaths are reported, and autochthonous circulation of the virus is reported in Brazil, Chile (on Easter Island), Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Suriname, and Venezuela.[51]

United Nations

On 1 December, PAHO releases a report noting the possible connection between the Zika virus and the rise in neurological syndromes. Three deaths are reported, and autochthonous circulation of the virus is reported in Brazil, Chile (on Easter Island), Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Suriname, and Venezuela.[51]

![]() Puerto Rico

On 31 December, the Puerto Rico Department of Health reported the first locally acquired case of Zika virus infection in Puerto Rico. Zika was confirmed in a resident of Puerto Rico with no known travel history.[52]

Puerto Rico

On 31 December, the Puerto Rico Department of Health reported the first locally acquired case of Zika virus infection in Puerto Rico. Zika was confirmed in a resident of Puerto Rico with no known travel history.[52]

January

![]() United States

On 17 January, a baby is born in Hawaii with the Zika virus and microcephaly, the first such case reported in the U.S.; the mother had lived in Brazil in May the previous year.[53]

United States

On 17 January, a baby is born in Hawaii with the Zika virus and microcephaly, the first such case reported in the U.S.; the mother had lived in Brazil in May the previous year.[53]

![]() Taiwan

On 19 January, a man from Thailand becomes the first imported case of Zika virus in Taiwan.[12]

Taiwan

On 19 January, a man from Thailand becomes the first imported case of Zika virus in Taiwan.[12]

![]() Samoa

On 26 January, Samoa is added to the CDC travel advisory.[54]

Samoa

On 26 January, Samoa is added to the CDC travel advisory.[54]

![]() Curaçao

On 31 January, Curaçao reports its first confirmed autochthonous case of Zika.[55]

Curaçao

On 31 January, Curaçao reports its first confirmed autochthonous case of Zika.[55]

February

![]() United Nations

On 1 February, the WHO declares the Zika virus outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).[13][56]

United Nations

On 1 February, the WHO declares the Zika virus outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).[13][56]

![]() United States

On 8 February, the Obama administration requests $1.8 billion in the fight against Zika.[57]

United States

On 8 February, the Obama administration requests $1.8 billion in the fight against Zika.[57]

![]() United States

On 11 February, the CDC releases preliminary guidelines regarding the sexual transmission of Zika. Three likely cases are reported.[58]

United States

On 11 February, the CDC releases preliminary guidelines regarding the sexual transmission of Zika. Three likely cases are reported.[58]

![]() United Nations

On 12 February, the WHO advises pregnant women to avoid travel to areas where the transmission of the Zika virus is active.[59]

United Nations

On 12 February, the WHO advises pregnant women to avoid travel to areas where the transmission of the Zika virus is active.[59]

![]() United States

On 12 February, the CDC releases a Level 2 (Practice Enhanced Precautions) travel notice.[60]

United States

On 12 February, the CDC releases a Level 2 (Practice Enhanced Precautions) travel notice.[60]

March

![]() United States

As of 9 March, the CDC reports 193 travel-associated Zika virus disease cases, and no locally acquired vector-borne cases.[61]

United States

As of 9 March, the CDC reports 193 travel-associated Zika virus disease cases, and no locally acquired vector-borne cases.[61]

![]() United States

On 24 March, a genetics study published in Science suggests that the Zika virus had arrived in Brazil between May and December 2013.[62]

United States

On 24 March, a genetics study published in Science suggests that the Zika virus had arrived in Brazil between May and December 2013.[62]

![]() United States

On 30 March, the New England Journal of Medicine published "Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities," which documents the destruction of a fetal brain by Zika in detail; the Finnish mother had been infected in the 11th gestational week whilst travelling in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize.[63]

United States

On 30 March, the New England Journal of Medicine published "Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities," which documents the destruction of a fetal brain by Zika in detail; the Finnish mother had been infected in the 11th gestational week whilst travelling in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize.[63]

![]() South Korea

On 22 March, a man from Brazil becomes the first imported case of Zika virus in South Korea.

South Korea

On 22 March, a man from Brazil becomes the first imported case of Zika virus in South Korea.

April

![]() United States On 1 April, the CDC holds a meeting at its headquarters with more than 300 local, state, and federal officials and experts to coordinate the response to Zika, including a reorganization of mosquito control programs.[64]

United States On 1 April, the CDC holds a meeting at its headquarters with more than 300 local, state, and federal officials and experts to coordinate the response to Zika, including a reorganization of mosquito control programs.[64]

![]() United States On 6 April the Obama administration, after a two-month long impasse with Congress, allocates $589 million in the fight against Zika (of which $510 million came from the $2.7 billion earmarked to battle the West African Ebola virus epidemic).[65]

United States On 6 April the Obama administration, after a two-month long impasse with Congress, allocates $589 million in the fight against Zika (of which $510 million came from the $2.7 billion earmarked to battle the West African Ebola virus epidemic).[65]

![]() Peru On 16 April, Peru reports its first case of sexual transmission (and its seventh overall) after a resident infected his wife after contracting the disease in Venezuela.[66]

Peru On 16 April, Peru reports its first case of sexual transmission (and its seventh overall) after a resident infected his wife after contracting the disease in Venezuela.[66]

![]() United States On 29 April, the CDC confirms the first Zika-related death in the US occurred in February 2016. Zika first appeared in Puerto Rico in December 2015.

United States On 29 April, the CDC confirms the first Zika-related death in the US occurred in February 2016. Zika first appeared in Puerto Rico in December 2015.

May

![]() United States On 13 May 2016, the CDC begins to recommend testing urine for clues to Zika infection.[68]

United States On 13 May 2016, the CDC begins to recommend testing urine for clues to Zika infection.[68]

![]() Belize On 16 May, Belize confirms its first case of Zika infection.[69]

Belize On 16 May, Belize confirms its first case of Zika infection.[69]

July

![]() United States On 29 July 2016, the CDC confirms 4 cases of locally transmitted cases of Zika infection in Miami, Florida, the first locally transmitted cases confirmed in the mainland US.[70]

United States On 29 July 2016, the CDC confirms 4 cases of locally transmitted cases of Zika infection in Miami, Florida, the first locally transmitted cases confirmed in the mainland US.[70]

August

![]()

![]() Florida, United States 1 August 2016 In response to confirmed cases of localized mosquito transmission of Zika in Miami's Wynwood neighborhood, the CDC issued an official travel warning for Miami, Florida.[71]

Florida, United States 1 August 2016 In response to confirmed cases of localized mosquito transmission of Zika in Miami's Wynwood neighborhood, the CDC issued an official travel warning for Miami, Florida.[71]

![]() Puerto Rico 12 August 2016, The U.S. government declares a public health emergency in Puerto Rico as a result of a Zika epidemic.[72]

Puerto Rico 12 August 2016, The U.S. government declares a public health emergency in Puerto Rico as a result of a Zika epidemic.[72]

![]() Singapore 27 August 2016, Singapore's Ministry of Health confirms the first case of locally transmitted Zika infections in the country.[73][74]

Singapore 27 August 2016, Singapore's Ministry of Health confirms the first case of locally transmitted Zika infections in the country.[73][74]

![]() Singapore 28 August 2016, Singapore's National Environment Agency and Ministry of Health confirms 41 cases of locally transmitted Zika virus infections in a joint statement. Most of these cases are said to have been among foreign construction workers, and the authorities stated they expected more cases to be identified. 34 of the cases made a full recovery, but 7 remain hospitalized.[75]

Singapore 28 August 2016, Singapore's National Environment Agency and Ministry of Health confirms 41 cases of locally transmitted Zika virus infections in a joint statement. Most of these cases are said to have been among foreign construction workers, and the authorities stated they expected more cases to be identified. 34 of the cases made a full recovery, but 7 remain hospitalized.[75]

![]() Singapore 29 August 2016, An additional 15 new cases of locally transmitted Zika infections are confirmed, bringing the total to 56 locally transmitted infections. The infections are traced to the Aljunied area in Singapore's south-east. Again, most of the infections were among foreign construction workers. Singapore's authorities step up prevention efforts including checking at-risk dormitories and spreading insect repellent.[73][74]

Singapore 29 August 2016, An additional 15 new cases of locally transmitted Zika infections are confirmed, bringing the total to 56 locally transmitted infections. The infections are traced to the Aljunied area in Singapore's south-east. Again, most of the infections were among foreign construction workers. Singapore's authorities step up prevention efforts including checking at-risk dormitories and spreading insect repellent.[73][74]

![]()

![]() Florida, United States 29 August 2016, after more locally transmitted cases of the Zika virus are reported in Southern Florida, Florida governor Rick Scott travels to Boca Raton in southern Florida to attend a roundtable discussion with tourism representatives, community officials and business leaders at the Boca Raton Resort. A total of 43 locally transmitted infections have now been contracted in Florida, the majority of which having occurred in Miami-Dade County. Miami Beach officials also say in a statement that the Miami Beach Botanical Garden would be temporarily closed off to visitors to prevent further spreading of the disease by mosquito bites.[76]

Florida, United States 29 August 2016, after more locally transmitted cases of the Zika virus are reported in Southern Florida, Florida governor Rick Scott travels to Boca Raton in southern Florida to attend a roundtable discussion with tourism representatives, community officials and business leaders at the Boca Raton Resort. A total of 43 locally transmitted infections have now been contracted in Florida, the majority of which having occurred in Miami-Dade County. Miami Beach officials also say in a statement that the Miami Beach Botanical Garden would be temporarily closed off to visitors to prevent further spreading of the disease by mosquito bites.[76]

![]() Malaysia 29 August 2016, Malaysian health authorities say in a press conference that it was "just a matter of time" until cases Zika are detected in Malaysia. Health minister Subramaniam Sathasivam states that there had not yet been any confirmed cases, despite it already being present in surrounding countries, and urges those returning from the Rio Olympics and other Zika-affected countries to undergo voluntary blood tests and screening, adding that most carriers are asymptomatic.[77]

Malaysia 29 August 2016, Malaysian health authorities say in a press conference that it was "just a matter of time" until cases Zika are detected in Malaysia. Health minister Subramaniam Sathasivam states that there had not yet been any confirmed cases, despite it already being present in surrounding countries, and urges those returning from the Rio Olympics and other Zika-affected countries to undergo voluntary blood tests and screening, adding that most carriers are asymptomatic.[77]

![]() Singapore 30 August 2016, the authorities of Australia, South Korea and Taiwan issue travel warnings against travel to Singapore over concerns about the spread of the Zika virus.[74][78]

Singapore 30 August 2016, the authorities of Australia, South Korea and Taiwan issue travel warnings against travel to Singapore over concerns about the spread of the Zika virus.[74][78]

September

![]() Malaysia 1 September 2016, Health Minister of Malaysia confirmed of the first case of Zika in Malaysia. The patient recently went to Singapore for three days. Vector control was intensified at the patient's area.[79]

Malaysia 1 September 2016, Health Minister of Malaysia confirmed of the first case of Zika in Malaysia. The patient recently went to Singapore for three days. Vector control was intensified at the patient's area.[79]

![]() Malaysia 3 September 2016, A locally transmitted infection was detected in Sabah, Malaysia. The patient did not travel overseas recently and was probably bitten by an Aedes mosquito.[80]

Malaysia 3 September 2016, A locally transmitted infection was detected in Sabah, Malaysia. The patient did not travel overseas recently and was probably bitten by an Aedes mosquito.[80]

![]() Singapore 5 September 2016, Singapore's Ministry of Health and National Environment Agency said that the total number of locally transmitted Zika virus infections over the weekend was 91, raising the total to 242. 83 of the new infections were connected to the Aljunied Crescent, Sims Drive, Kallang Way, and Paya Lebar Way areas, with a potential new cluster with two reported cases in the Seng Road area.[74]

Singapore 5 September 2016, Singapore's Ministry of Health and National Environment Agency said that the total number of locally transmitted Zika virus infections over the weekend was 91, raising the total to 242. 83 of the new infections were connected to the Aljunied Crescent, Sims Drive, Kallang Way, and Paya Lebar Way areas, with a potential new cluster with two reported cases in the Seng Road area.[74]

![]()

![]() Florida, United States 19 September 2016 The CDC lifts official travel guidelines for Miami, Florida.[81][82]

Florida, United States 19 September 2016 The CDC lifts official travel guidelines for Miami, Florida.[81][82]

October

![]() Vietnam 30 October 2016, Vietnam's Health Ministry has reported a microcephaly case that it says is likely to be the country's first linked to the mosquito-borne Zika virus.[83]

Vietnam 30 October 2016, Vietnam's Health Ministry has reported a microcephaly case that it says is likely to be the country's first linked to the mosquito-borne Zika virus.[83]

References

- Gatherer, Derek; Kohl, Alain (2016). "Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas" (PDF). Journal of General Virology. 97 (2): 269–273. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000381. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 26684466.

- "Zika virus in the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Lanciotti, Robert S.; Lambert, Amy J.; Holodniy, Mark; et al. (2016). "Phylogeny of Zika Virus in Western Hemisphere, 2015". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (5): 933–935. doi:10.3201/eid2205.160065. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4861537. PMID 27088323.

- Kindhauser, Mary Kay; Allen, Tomas; Frank, Veronika; et al. (2016). "Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 94 (9): 675–686C. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.171082. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 5034643. PMID 27708473. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016.

- "Zika virus: first described in Transactions!". News. Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Dick, G.W.; Kitchen, S.F.; Haddow, A.J. (September 1952). "Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 46 (5): 509–20. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. PMID 12995440.

- MacNamara, F.N. (March 1954). "Zika virus: a report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 48 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(54)90006-1. PMID 13157159.

- Bearcroft, W.G. (September 1956). "Zika virus infection experimentally induced in a human volunteer". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 50 (5): 442–8. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(56)90091-8. PMID 13380987.

- "Timeline - Zika's origin and global spread". Fox News. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Timeline: Zika's origin and global spread". Reuters. 12 February 2016.

- Hayes, Edward B. (September 2009). "Zika virus outside Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (9): 1347–50. doi:10.3201/eid1509.090442. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 2819875. PMID 19788800.

- Silver, Marc (5 February 2016). "Mapping Zika: From A Monkey In Uganda To A Growing Global Concern". NPR. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Sikka, Veronica; Chattu, Vijay Kumar; Popli, Raaj K.; et al. (11 February 2016). "The emergence of zika virus as a global health security threat: A review and a consensus statement of the INDUSEM Joint working Group (JWG)". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 8 (1): 3–15. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.176140. ISSN 0974-8245. PMC 4785754. PMID 27013839.

- Duffy, Mark R.; Chen, Tai-Ho; Hancock, W. Thane (11 June 2009). "Zika virus outbreak on Yap Islands, Federated States of Micronesia". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (24): 2536–43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. PMID 19516034.

- de Bernardi Schneider, Adriano; Malone, Robert W.; Guo, Jun-Tao; Homan, Jane; Linchangco, Gregorio; Witter, Zachary L.; Vinesett, Dylan; Damodaran, Lambodhar; Janies, Daniel A. (1 February 2017). "Molecular evolution of Zika virus as it crossed the Pacific to the Americas". Cladistics. 33 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/cla.12178. ISSN 1096-0031. PMID 34724757.

- Olson, Ken E.; Haddow, Andrew D.; Schuh, Amy J.; et al. (2012). "Genetic Characterization of Zika Virus Strains: Geographic Expansion of the Asian Lineage". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (2): e1477. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3289602. PMID 22389730.

- Lanciotti, Robert S.; Kosoy, Olga L.; Laven, Janeen J.; et al. (2008). "Genetic and Serologic Properties of Zika Virus Associated with an Epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (8): 1232–1239. doi:10.3201/eid1408.080287. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2600394. PMID 18680646.

- Buathong, R.; Hermann, L.; Thaisomboonsuk, B.; et al. (2015). "Detection of Zika Virus Infection in Thailand, 2012-2014". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 93 (2): 380–383. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0022. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 4530765. PMID 26101272.

- Mallet, Dr. Henri-Pierre (27 October 2013). "Zika Virus - French Polynesia". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Berger, Stephen (3 February 2015). Chikungunya and Zika: Global Status (2015 ed.). GIDEON Informatics, Inc. p. 75. ISBN 9781498806978. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Roth, A; Mercier, A; Lepers, C; et al. (2014). "Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections – an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012–2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (41): 20929. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.41.20929. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 25345518.

- Mole, Beth (16 January 2016). "Zika: Here's what we know about the virus alarming health experts worldwide: Despite a long history, Zika remains an enigmatic, emerging infectious disease". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Besnard, M; Lastère, S; Teissier, A; et al. (2014). "Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (13): 20751. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.13.20751. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 24721538.

- Musso, D; Nhan, T; Robin, E; et al. (2014). "Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (14): 20761. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.14.20761. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 24739982.

- "Zika virus infection outbreak, Brazil and the Pacific region" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 May 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Musso, Didier; Roche, Claudine; Robin, Emilie; Nhan, Tuxuan; Teissier, Anita; Cao-Lormeau, Van-Mai (2015). "Potential Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus" (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21 (2): 359–361. doi:10.3201/eid2102.141363. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4313657. PMID 25625872.

- Kutsuna, Dr. Satoshi (18 December 2013). "Zika Virus - Japan: ex French Polynesia". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Zika Virus - Pacific (03): New Caledonia". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Pyke, Alyssa T.; Daly, Michelle T.; Cameron, Jane N.; et al. (2014). "Imported Zika Virus Infection from the Cook Islands into Australia, 2014". PLOS Currents. 6. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.4635a54dbffba2156fb2fd76dc49f65e. ISSN 2157-3999. PMC 4055592. PMID 24944843. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Schwan, Katharina (7 March 2014). "First Case of Zika Virus reported on Easter Island". The Disease Daily. HealthMap. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "BANGLADESH CONFIRMS FIRST CASE OF ZIKA VIRUS". Newsweek. Reuters. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Zika virus infection outbreak, Brazil and the Pacific region" (PDF). Rapid Risk Assessment. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 May 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Zanluca C, Melo VC, Mosimann AL, Santos GI, Santos CN, Luz K (June 2015). "First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 110 (4): 569–72. doi:10.1590/0074-02760150192. PMC 4501423. PMID 26061233.

- Faria, Nuno Rodrigues; et al. (24 March 2016). "A single introduction of ZIKV into the Americas more than 12 months prior to the detection of ZIKV in Brazil". Science. 352 (6283): 345–349. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5036. PMC 4918795. PMID 27013429.

- Willie, Glenda (27 April 2015). "Zika and dengue cases confirmed". Vanuatu Daily Post. Port Vila. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Zika Virus - Brazil: Confirmed". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Increase of microcephaly in the northeast of Brazil". Epidemiological Alert. Pan American Health Organization. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Bichell, Rae Ellen (10 February 2016). "Zika Virus: What Happened When". Health Shots. National Public Radio.

- Kindhauser, Mary Kay; Allen, Tomas; Frank, Veronika; Santhana, Ravi; Dye, Christopher (2016). "Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 94 (9): 675–686C. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.171082. PMC 5034643. PMID 27708473. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Sweeney, John (13 February 2016). "Colombia: A nation concerned over Zika". BBC Health. BBC.

- Kindhauser, Mary Kay (9 February 2016). "Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 94 (9): 675–686C. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.171082. PMC 5034643. PMID 27708473. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Zika virus infection – Suriname". Disease Outbreak News. WHO. 11 November 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Ministério da Saúde investiga aumento de casos de microcefalia em Pernambuco" [Ministry of Health investigates increase in microcephaly cases in Pernambuco]. Portal da Saúde (in Portuguese). Ministério da Saúde. 11 November 2015.

- McNeil Jr., Donald G; Saint Louis, Catherine; St. Fleur, Nicholas (3 February 2016). "Short Answers to Hard Questions About Zika Virus". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 24 November 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "Zika virus infection – El Salvador". Disease Outbreak News. WHO. March 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Zika virus infection – Mexico". Disease Outbreak News. WHO. March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "First Paraguayan cases". Disease Outbreak News. WHO. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Zika virus infection – Venezuela". Disease Outbreak News. WHO. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Zika Virus in the Pacific Islands". Travelers' Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas". Epidemiological Alert. Pan American Health Organization. 1 December 2015.

- "First case of Zika virus reported in Puerto Rico". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 31 December 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- McNeil Jr., Donald G. (16 January 2016). "Hawaii Reports Baby Born With Brain Damage Linked to Zika Virus". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Hardy, Rachel (26 January 2016). "Samoa added to Zika travel advisory". Quadrangle Online.

- "Zika Country List Expands; Curaçao Reports, Colombia Sees GBS Spike". Curaçao Chronicle. Core Communications. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- "WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome". Media Centre. World Health Organization. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Mole, Beth (8 February 2016). "Obama says no need to panic over Zika, requests $1.8 billion: Republicans talk quarantines amid fund request for vaccines, mosquito control". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Oster, Alexandra M.; Brooks, John T.; Stryker, Jo Ellen; et al. (2016). "Interim Guidelines for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus — United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (5): 120–121. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6505e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 26866485.

- Cha, Ariana Eunjung (12 February 2016). "In new advisory, WHO warns pregnant women against travel to Zika-affected countries". The Washington Post.

- "Zika: Pregnant? Read this before you travel" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- "Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 March 2016. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Mole, Beth (24 March 2016). "Zika may have skulked around Brazil for more than a year unnoticed: Genetic study pegs virus' arrival to 2013, letting 2014 World Cup off the hook". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Driggers, Rita W. (30 March 2016). "Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (22): 2142–2151. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. PMID 27028667.

- Mole, Beth (1 April 2016). "CDC braces for Zika's US invasion as scientists watch virus melt fetal brain: Experts prepare for pockets of transmission on US mainland as mosquito season begins". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Mole, Beth (16 April 2016). "After standoff with Congress, White House robs Ebola fund to pay for Zika: Administration urges Republicans to approve money to prevent US outbreaks". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Esposito, Anthony (16 April 2016). "Peru reports first case of sexually transmitted Zika virus". Zika News. Reuters. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "Diagnostic Testing of Urine Specimens for Suspected Zika Virus Infection - Infection Control Today". Infection Control Today. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Belize Confirms First Case of Zika - The San Pedro Sun News". The San Pedro Sun. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Florida investigation links four recent Zika cases to local mosquito-borne virus transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- "CDC Press Releases". January 2016.

- Coto, Danica (12 August 2016). "US declares health emergency in Puerto Rico due to Zika". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Lee, Nicole; Branddick, Imogen (29 August 2016). "Singapore steps up Zika prevention effort as confirmed cases rise to 56". Reuters. Singapore. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- "Tracking Singapore's Zika outbreak". Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Zaharia, Marius (28 August 2016). "Singapore confirms 41 cases of locally-transmitted Zika virus". Reuters. Singapore. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Vela, Hatzel; Batchelor, Amanda (29 August 2016). "Governor back in South Florida as additional Zika virus transmission reported in Miami Beach". Local10. Boca Raton, Florida: ABC. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Goh, Melissa (29 August 2016). "'Just a matter of time' before Malaysia detects first Zika case: Health officials". Channel NewsAsia. Putrajaya, Malaysia. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Zaharia, Marius (30 August 2016). "Singapore confirms Zika spread; some countries issue travel warnings". Reuters. Singapore. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- "Malaysia confirms first case of Zika". ABC News. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Malaysia detects first case of locally transmitted Zika". ABC News. 3 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "CDC lifts travel ban as Miami neighborhood declared Zika free". USA Today.

- "CDC LIFTS TRAVEL BAN ON MIAMI NEIGHBORHOOD". stdtestexpress.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- "Zika: Vietnamese authorities report first microcephaly case likely linked to mosquito-borne virus". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.