Land reform in Zimbabwe

Land reform in Zimbabwe officially began in 1980 with the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement, as an effort to more equitably distribute land between black subsistence farmers and white Zimbabweans of European ancestry, who had traditionally enjoyed superior political and economic status. The programme's stated targets were intended to alter the ethnic balance of land ownership.[1]

The government's land distribution is perhaps the most crucial and most bitterly contested political issue surrounding Zimbabwe. It has been criticised for the violence and intimidation which marred several expropriations, as well as the parallel collapse of domestic banks which held billions of dollars' worth of bonds on liquidated properties.[2] The United Nations has identified several key shortcomings with the contemporary programme, namely failure to compensate ousted landowners as called for by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the poor handling of boundary disputes, and chronic shortages of material and personnel needed to carry out resettlement in an orderly manner.[3] Seven farm owners and more farm workers have been killed during violent takeovers.[4]

Land reform has had a serious negative effect on the Zimbabwean economy and is argued to have heavily contributed to its collapse in the 2000s.[5][6] There has been a drop in total farm output which has led to instances of starvation and famine.[7] Increasing poverty levels combined with the increased informality of farming operations amongst farmers who received redistributed land has led to an increase in the use of child labour especially in the growing of sugar cane.[8]

As of 2011, 237,858 Zimbabwean households had been provided with access to land under the programme. A total of 10,816,886 hectares had been acquired since 2000, compared to the 3,498,444 purchased from voluntary sellers between 1980 and 1998.[3] By 2013, every white-owned farm in Zimbabwe had been either expropriated or confirmed for future redistribution.[9] The compulsory acquisition of farmland without compensation was discontinued in early 2018.[10] In 2019, the Commercial Farmers Union stated that white farmers who had land expropriated under the fast track program had agreed to accept an interim compensation offer by the Zimbabwean government of RTGS$53 million (US$17 million) as part of the government effort to compensate dispossessed farmers.[11] A year later, the Zimbabwean government announced that it would be compensating dispossessed white farmers for infrastructure investments in the land and had committed to pay out US$3.5 billion.[12][13]

Background

The foundation for the controversial land dispute in Zimbabwean society was laid at the beginning of European settlement of the region, which had long been the scene of mass movements by various Bantu peoples. In the sixteenth century, Portuguese explorers had attempted to open up Zimbabwe for trading purposes, but the country was not permanently settled by European immigrants until three hundred years later.[14] The first great Zimbabwean kingdom was the Rozwi Empire, established in the eleventh century. Two hundred years later, Rozwi imperial rule began to crumble and the empire fell to the Karanga peoples, a relatively new tribe to the region which originated north of the Zambezi River.[14] Both these peoples later came to form the nucleus of the Shona civilisation, along with the Zezuru in central Zimbabwe, the Korekore in the north, the Manyika in the east, the Ndau in the southeast, and the Kalanga in the southwest.[14]

Most Shona cultures had a theoretically communal attitude towards land ownership; the later European concept of officiating individual property ownership was unheard of.[15] Land was considered the collective property of all the residents in a given chiefdom, with the chief mediating disagreements and issues pertaining to its use.[15] Nevertheless, male household heads frequently reserved personal tracts for their own cultivation, and allocated smaller tracts to each of their wives. Population growth frequently resulted in the over-utilisation of the existing land, which became greatly diminished both in terms of cultivation and grazing due to the larger number of people attempting to share the same acreage.[15]

During the early nineteenth century, the Shona were conquered by the Northern Ndebele (also known as the Matabele), which began the process of commodifying Zimbabwe's land.[14] Although the Ndebele elite were uninterested in cultivation, land ownership was considered one major source of an individual's wealth and power—the others being cattle and slaves. Ndebele monarchs acquired large swaths of land for themselves accordingly.[14]

Land hunger was at the centre of the Rhodesian Bush War, and was addressed at Lancaster House, which sought to concede equitable redistribution to the landless without damaging the white farmers' vital contribution to Zimbabwe's economy.[16] At independence from the United Kingdom in 1980, the Zimbabwean authorities were empowered to initiate the necessary reforms; as long as land was bought and sold on a willing basis, the British government would finance half the cost.[16] In the late 1990s, Prime Minister Tony Blair terminated this arrangement when funds available from Margaret Thatcher's administration were exhausted, repudiating all commitments to land reform. Zimbabwe responded by embarking on a "fast track" redistribution campaign, forcibly confiscating white farms without compensation.[16]

European settlement patterns

The first white colonists to settle in modern-day Zimbabwe arrived during the 19th century, primarily from the Cape Colony (modern-day South Africa), less than a century after the Ndebele invasions.[17] This reflected a larger trend of permanent European settlement in the milder, drier regions of Southern Africa as opposed to the tropical and sub-tropical climates further north.[18] In 1889 Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company (BSAC) introduced the earliest white settlers to Zimbabwe as prospectors, seeking concessions from the Ndebele for mineral rights.[14] Collectively known as the Pioneer Column, the settlers established the city of Salisbury, now Harare.[14] Rhodes hoped to discover gold and establish a mining colony, but the original intention had to be modified as neither the costs nor the returns on the overhead capital matched the original projections.[19] Local gold deposits failed to yield the massive returns which the BSAC had promised its investors, and the military costs of the expedition had caused a deficit.[19] An interim solution was the granting of land to the settlers in the hopes that they would develop productive farms and generate enough income to justify the colony's continued administrative costs.[19] The region was demarcated as Southern Rhodesia after 1898.[20]

Between 1890 and 1896, the BSAC granted an area encompassing 16 million acres—about one sixth the area of Southern Rhodesia—to European immigrants.[19] By 1913 this had been extended to 21.5 million acres. However, these concessions were strictly regulated, and land was only offered to those individuals able to prove they had the necessary capital to develop it.[19] Exceptions were made during the Ndebele and Shona insurrections against the BSAC in the mid-1890s, when land was promised to any European men willing to take up arms in defence of the colony, irrespective of their financial status.[21] The settlers of the Pioneer Column were granted tracts of 3,150 acres apiece, with an option to purchase more land from the BSAC's holdings at relatively low prices (up to fifteen times cheaper than comparable land on the market in South Africa).[19]

Creation of the Tribal Trust Lands

Friction soon arose between the settlers and the Ndebele and Shona peoples, both in terms of land apportionment and economic competition.[19] In 1900, Southern Rhodesia's black population owned an estimated 55,000 head of cattle, while European residents owned fewer than 12,000. Most of the pastureland was being grazed by African-owned cattle, accordingly.[22] However, in less than two decades the Ndebele and Shona came to own over a million head of cattle, with white farmers owning another million as well.[22] As the amount of available pasture for the livestock quickly dwindled, accompanied by massive amounts of overgrazing and erosion, land competition between the three groups became intense.[22] A number of successive land commissions were thus appointed to study the problem and apportion the land.[22]

The colonial government in Southern Rhodesia delineated the country into five distinct farming regions which corresponded roughly to rainfall patterns.[22] Region I comprised an area in the eastern highlands with markedly higher rainfall best suited to the cultivation of diversified cash crops such as coffee and tea. Region II was highveld, also in the east, where the land could be used intensively for grain cultivation such as maize, tobacco, and wheat. Region III and Region IV endured periodic drought and were regarded as suitable for livestock, in addition to crops which required little rainfall. Region V was lowveld and unsuitable for crop cultivation due to its dry nature; however, limited livestock farming was still viable.[23] Land ownership in these regions was determined by race under the terms of the Southern Rhodesian Land Apportionment Act, passed in 1930, which reserved Regions I, II, and III for white settlement.[23] Region V and a segment of Region II which possessed greater rainfall variability were organised into the Tribal Trust Lands (TTLs), reserved solely for black African ownership and use.[22] This created two new problems: firstly, in the areas reserved for whites, the ratio of land to population was so high that many farms could not be exploited to their fullest potential, and some prime white-owned farmland was lying idle.[19] Secondly, the legislation resulted in enforced overuse of the land in the TTLs due to overpopulation there.[22]

The Southern Rhodesian Land Apportionment Act reserved 49 million acres for white ownership and left 17.7 million acres of land unassigned to either the white preserve or the TTLs.[19] While a survey undertaken by the colony's Land Commission in concert with the British government in 1925 found that the vast majority of black Rhodesians supported some form of geographic segregation, including the reservation of land exclusively for their use, many were disillusioned by the manner in which the legislation was implemented in explicit favour of whites.[19] The overcrowded conditions in the TTLs compelled large numbers of Shona and Ndebele alike to abandon their rural livelihoods and seek wage employment in the cities or on white commercial farms.[23] Those who remained on tracts in the TTLs found themselves having to cope with topsoil depletion due to overuse; large amounts of topsoil were stripped of their vegetation cover and rendered unproductive as a consequence.[22] To control the rate of erosion, colonial authorities introduced voluntary destocking initiatives for livestock. When these met with little success, the destocking programme became mandatory in 1941, forcing all residents of the TTLs to sell or slaughter animals declared surplus.[22] Another 7.2 million acres were also set aside for sale to black farmers, known as the Native Purchase Areas.[19]

During the early 1950s, Southern Rhodesia passed the African Land Husbandry Act, which attempted to reform the communal system in the TTLs by giving black Africans the right to apply for formal title deeds to specific tracts.[22] This legislation proved so unpopular and difficult to enforce that incoming Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith ordered its suspension in the mid-1960s. Smith's administration subsequently recognised the traditional leaders of each chiefdom as the final authority on land allocation in the TTLs.[22]

Following Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence, land legislation was again amended with the Rhodesian Land Tenure Act of 1969. The Land Tenure Act upended the Land Apportionment Act of 1930 and was designed to rectify the issue of insufficient land available to the rapidly expanding black population.[22] It reduced the amount of land reserved for white ownership to 45 million acres and reserved another 45 million acres for black ownership, introducing parity in theory; however, the most fertile farmland in Regions I, II, and III continued to be included in the white enclave.[22] Abuses of the system continued to abound; some white farmers took advantage of the legislation to shift their property boundaries into land formerly designated for black settlement, often without notifying the other landowners.[24] A related phenomenon was the existence of black communities, especially those congregated around missions, which were oblivious to the legislation and unwittingly squatting on land redesignated for white ownership. The land would be sold in the meantime, and the government obliged to evict the preexisting occupants.[25] These incidents and others were instrumental in eliciting sympathy among Rhodesia's black population for nationalist movements such as the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), which sought to overthrow the Rhodesian government by force of arms.[25]

The Bush War and Lancaster House

The escalation of the Rhodesian Bush War in the 1970s led to a significant amount of rural displacement and interrupted agricultural activity.[23] The disruption of veterinary services resulted in massive livestock losses, and the cultivation of cash crops was hampered by guerrilla raids.[25] The murder of about three hundred white farmers during the war, as well as the conscription of hundreds of others into the Rhodesian Security Forces, also led to a drop in the volume of agricultural production.[26] Between 1975 and 1976 Rhodesia's urban population doubled as thousands of rural dwellers, mostly from TTLs, fled to the cities to escape the fighting.[23] A campaign of systematic villagisation followed as the Rhodesian Army shifted segments of the black population into guarded settlements to prevent their subversion by the insurgents.[25]

In 1977, the Land Tenure Act was amended by the Rhodesian parliament, which further reduced the amount of land reserved for white ownership to 200,000 hectares, or 500,000 acres. Over 15 million hectares were thus opened to purchase by persons of any race.[22] Two years later, as part of the Internal Settlement, Zimbabwe Rhodesia's incoming biracial government under Bishop Abel Muzorewa abolished the reservation of land according to race.[22] White farmers continued to own 73.8% of the most fertile land suited for intensive cash crop cultivation and livestock grazing, in addition to generating 80% of the country's total agricultural output.[22] This was a vital contribution to the economy, which was still underpinned by its agricultural exports.[23]

Land reform emerged as a critical issue during the Lancaster House Talks to end the Rhodesian Bush War. ZANU leader Robert Mugabe and ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo insisted on the redistribution of land—by compulsory seizure, without compensation—as a precondition to a negotiated peace settlement.[27] This was reflective of prevailing attitudes in their guerrilla armies, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) respectively, and rural support bases, which had high expectations of the redistribution of land.[16][23] The British government, which mediated the talks, proposed a constitutional clause underscoring property ownership as an inalienable right to prevent a mass exodus of white farmers and the economic collapse of the country.[26] This was enshrined in Section 16 of the Zimbabwean Constitution, 1980.[27] To secure Mugabe and Nkomo's support for the constitutional agreement, Lord Carrington announced that the United Kingdom would be prepared to assist land resettlement with technical assistance and financial aid.[27] The Secretary-General of the Commonwealth of Nations, Sir Shridath Ramphal, also received assurances from the American ambassador in London, Kingman Brewster, that the United States would likewise contribute capital for "a substantial amount for a process of land redistribution and they would undertake to encourage the British government to give similar assurances".[28]

The Lancaster House Agreement stipulated that farms could only be taken from whites on a "willing buyer, willing seller" principle for at least ten years.[16] White farmers were not to be placed under any pressure or intimidation, and if they decided to sell their farms they were allowed to determine their own asking prices.[16] Exceptions could be made if the farm was unoccupied and not being used for agricultural activity.[27]

Southern Rhodesia's independence was finally recognised as the Republic of Zimbabwe on April 18, 1980. As Zimbabwe's first prime minister, Mugabe reaffirmed his commitment to land reform.[22] The newly created Zimbabwean Ministry of Lands, Resettlement, and Redevelopment announced later that year that land reform would be necessary to alleviate overpopulation in the former TTLs, extend the production potential of small-scale subsistence farmers, and improve the standards of living of rural blacks.[23] Its stated goals were to ensure abandoned or under-utilised land was being exploited to its fullest potential, and provide opportunities for unemployed, landless peasants.[23]

Post-independence

Inequalities in land ownership were inflated by a growing overpopulation problem, depletion of over-utilised tracts, and escalating poverty in subsistence areas parallel with the under-utilisation of land on commercial farms.[2] The predominantly white commercial sector used the labor of over 30% of the paid workforce and accounted for some 40% of exports.[22] Its principal crops included sugarcane, coffee, cotton, tobacco and several varieties of high-yield hybrid maize. Both the commercial farms and the subsistence sector maintained large cattle herds, but over 60% of domestic beef was furnished by the former.[22] In sharp contrast, the life of typical subsistence farmers was difficult, and their labour poorly rewarded. As erosion increased, the ability of the subsistence sector to feed its adherents diminished greatly.[2]

Phases of land reform

Willing Seller, Willing Buyer

Despite extensive financial assistance from the UK, the first phase of Zimbabwe's land reform programme was widely regarded as unsuccessful.[23] Zimbabwe was only able to acquire 3 million hectares (7.41 million acres) for black resettlement, well short of its intended target of 8 million hectares (19.77 million acres).[29] This land was redistributed to about 50,000 households.[29] Many former supporters of the nationalist movements felt that the promises of Nkomo and Mugabe with regards to the land had not been truly fulfilled. This sentiment was especially acute in Matabeleland, where the legacy of the Southern Rhodesian Land Apportionment Act was more disadvantageous to black Zimbabweans than other parts of the country.[30]

Funds earmarked for the purchase of white farms were frequently diverted into defence expenditure throughout the mid-1980s, for which Zimbabwean officials received some criticism.[30] Reduction of funding posed another dilemma: property prices were now beyond what the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement, and Redevelopment could afford to meet its goals.[31] It was also unable to build sufficient roads, clinics, and schools for the large number of people it was resettling in new areas.[31] After 1983, the domestic budget could no longer sustain resettlement measures, and despite British aid the number of farms being purchased gradually declined for the remainder of the decade.[32]

In 1986, the government of Zimbabwe cited financial restraints and an ongoing drought as the two overriding factors influencing the slow progress of land reform.[33] However, it was also clear that within the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement, and Redevelopment itself there was a lack of initiative and trained personnel to plan and implement mass resettlements.[33] Parliament passed the Land Acquisition Act in 1985, which gave the government first right to purchase excess land for redistribution to the landless. It empowered the government to claim tracts adjacent to the former TTLs (now known simply as "Communal Areas") and mark them for resettlement purposes, provided the owners could be persuaded to sell.[33]

Between April 1980 and September 1987, the acreage of land occupied by white-owned commercial farms was reduced by about 20%.[33]

Compulsory acquisition

After the expiration of the entrenched constitutional conditions mandated by the Lancaster House Agreement in the early 1990s, Zimbabwe outlined several ambitious new plans for land reform.[32] A National Land Policy was formally proposed and enshrined as the Zimbabwean Land Acquisition Act of 1992, which empowered the government to acquire any land as it saw fit, although only after payment of financial compensation.[32] While powerless to challenge the acquisition itself, landowners were permitted some lateral to negotiate their compensation amounts with the state.[16] The British government continued to help fund the resettlement programme, with aid specifically earmarked for land reform reaching £91 million by 1996.[29] Another £100 million was granted for "budgetary support" and was spent on a variety of projects, including land reform.[29] Zimbabwe also began to court other donors through its Economic Structural Adjustment Policies (ESAP), which were projects implemented in concert with international agencies and tied to foreign loans.[23]

The diversion of farms for personal use by Zimbabwe's political elite began to emerge as a crucial issue during the mid-1990s.[32] Prime Minister Mugabe, who assumed an executive presidency in 1987, had urged restraint by enforcing a leadership code of conduct which barred members of the ruling party, ZANU–PF, from monopolising large tracts of farmland and then renting them out for profit.[34] Local media outlets soon exposed huge breaches of the code by Mugabe's family and senior officials in ZANU–PF.[34] Despite calls for accountability, the party members were never disciplined.[34] Instead of being resettled by landless peasants, several hundred commercial farms acquired under the Land Acquisition Act continued to be leased out by politically connected individuals.[32] In 1994, a disproportionate amount of the land being acquired was held by fewer than 600 black landowners, many of whom owned multiple properties.[32] One study of commercial farms found that over half the redistributed land that year went to absentee owners otherwise unengaged in agriculture.[32]

The perceived monopolisation of land by the ruling party provoked intense opposition from the ESAP donor states, which argued that those outside the patronage of ZANU-PF were unlikely to benefit.[35] In 1996, party interests became even more inseparable from the issue of land reform when President Mugabe gave ZANU–PF's central committee overriding powers—superseding those of the Zimbabwean courts as well as the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture—to delegate on property rights.[35] That year all farms marked for redistribution were no longer chosen or discussed by government ministries, but at ZANU–PF's annual congress.[35]

In 1997 the government published a list of 1,471 farms it intended to buy compulsorily for redistribution.[35] The list was compiled via a nationwide land identification exercise undertaken throughout the year. Landowners were given thirty days to submit written objections.[35] Many farms were delisted and then re-listed as the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture debated the merits of acquiring various properties,[32] especially those which ZANU–PF had ordered be expropriated for unspecified "political reasons".[35] Of the 1,471 individual property acquisitions, about 1,200 were appealed to the courts by the farmowners due to various legal irregularities.[35] President Mugabe responded by indicating that in his opinion land reform was a strictly political issue, not one to be questioned or debated by the judiciary.[35]

The increasing politicisation of land reform was accompanied by the deterioration of diplomatic relations between Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom.[35] Public opinion on the Zimbabwean land reform process among British citizens was decidedly mediocre; it was perceived as a poor investment on the part of the UK's government in an ineffectual and shoddily implemented programme.[35] In June 1996, Lynda Chalker, British secretary of state for international development, declared that she could not endorse the new compulsory acquisition policy and urged Mugabe to return to the principles of "willing buyer, willing seller".[35]

On 5 November 1997, Chalker's successor, Clare Short, described the new Labour government's approach to Zimbabwean land reform. She said that the UK did not accept that Britain had a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe. Notwithstanding the Lancaster House commitments, Short stated that her government was only prepared to support a programme of land reform that was part of a poverty eradication strategy. She had other questions regarding the way in which land would be acquired and compensation paid, and the transparency of the process. Her government's position was spelt out in a letter to Zimbabwe's Agriculture Minister, Kumbirai Kangai:[36]

- I should make it clear that we do not accept that Britain has a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe. We are a new government from diverse backgrounds without links to former colonial interests. My own origins are Irish and, as you know, we were colonised, not colonisers.

The letter concluded by stating that a programme of rapid land acquisition would be impossible to support, citing concern about the damage which this might do to Zimbabwe's agricultural output and its prospects of attracting investment.[36][37]

Kenneth Kaunda, former president of Zambia, responded dismissively by saying "when Tony Blair took over in 1997, I understand that some young lady in charge of colonial issues within that government simply dropped doing anything about it."[38]

In June 1998, the Zimbabwe government published its "policy framework" on the Land Reform and Resettlement Programme Phase II (LRRP II), which envisaged the compulsory purchase over five years of 50,000 square kilometres from the 112,000 square kilometres owned by white commercial farmers, public corporations, churches, non-governmental organisations and multinational companies. Broken down, the 50,000 square kilometres meant that every year between 1998 and 2003, the government intended to purchase 10,000 square kilometres for redistribution.

In September 1998, the government called a donors conference in Harare on LRRP II to inform the donor community and involve them in the program: Forty-eight countries and international organisations attended and unanimously endorsed the land program, saying it was essential for poverty reduction, political stability and economic growth. They agreed that the inception phase, covering the first 24 months, should start immediately, particularly appreciating the political imperative and urgency of the proposal.

The Commercial Farmers Union freely offered to sell the government 15,000 square kilometres for redistribution, but landowners once again dragged their feet. In response to moves by the National Constitutional Assembly, a group of academics, trade unionists and other political activists, the government drafted a new constitution. The draft was discussed widely by the public in formal meetings and amended to include restrictions on presidential powers, limits to the presidential term of office, and an age limit of 70 for presidential candidates. This was not seen as a suitable outcome for the government, so the proposals were amended to replace those clauses with one to compulsorily acquire land for redistribution without compensation. The opposition mostly boycotted the drafting stage of the constitution claiming that this new version was to entrench Mugabe politically.

Guerrilla veterans of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) began to emerge as a radical force in the land issue around this time. The guerrillas forcefully presented their position that white-owned land in Zimbabwe was rightfully theirs, on account of promises made to them during the Rhodesian Bush War.[32] Calls for accelerated land reform were also echoed by an affluent urban class of black Zimbabweans who were interested in making inroads into commercial farming, with public assistance.[32]

Fast-track land reform and violence

"Under those [sic] Bippas [Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements], which you allegedly say were violated, the only shortcoming was that we failed to raise the money to pay compensation, but there was no violation."

– Patrick Chinamasa, Zimbabwe Finance Minister (2014)[39]

The government held a referendum on the new constitution on 12–13 February 2000, despite having a sufficiently large majority in parliament to pass any amendment it wished. Had it been approved, the new constitution would have empowered the government to acquire land compulsorily without compensation. Despite vast support in the media, the new constitution was defeated, 55% to 45%.

On 26–27 February 2000,[40] the pro-Mugabe Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association (ZNLWVA) organised several people (including but not limited to war veterans; many of them were their children and grandchildren) to march on white-owned farmlands, initially with drums, song and dance. This movement was officially termed the "Fast-Track Land Reform Program" (FTLRP). The predominantly white farm owners were forced off their lands along with their workers, who were typically of regional descent. This was often done violently and without compensation. In this first wave of farm invasions, a total of 110,000 square kilometres of land had been seized. Several million black farm workers were excluded from the redistribution, leaving them without employment. According to Human Rights Watch, by 2002 the War Veterans Association had "killed white farm owners in the course of occupying commercial farms" on at least seven occasions, in addition to "several tens of [black] farm workers".[4] The first white farmers to die as a direct consequence of the resettlement programme were murdered by Zimbabwean paramilitaries in mid-2000. More commonly, violence was directed against farmworkers, who were often assaulted and killed by the war veterans and their supporters.[41] Violent confrontations between the farmers and the war veterans occurred and resulted in exchanges of gunfire, as well as a state of armed siege on the affected farms.[42]

Officially the land was divided into small-holder production, so called A1 schemes and commercial farms, called A2 schemes. There is however much overlap between the two categories.[43]

The violent takeover of Alamein Farm by retired Army General Solomon Mujuru sparked the first legal action against one of Robert Mugabe's inner circle.[44][45] In late 2002 the seizure was ruled illegal by the High and Supreme Courts of Zimbabwe; however the previous owner was unable to effect the court orders and General Mujuru continued living at the farm until his death on 15 August 2011.[46][47] Many other legal challenges to land acquisition or to eviction were not successful.[48]

On 10 June 2004, a spokesperson for the British embassy, Sophie Honey, said:[49]

- The UK has not reneged on commitments (made) at Lancaster House. At Lancaster House the British Government made clear that the long-term requirements of land reform in Zimbabwe were beyond the capacity of any individual donor country.

- Since [Zimbabwe's] independence we have provided 44 million pounds for land reform in Zimbabwe and 500 million pounds in bilateral development assistance.

- The UK remains a strong advocate for effective, well managed and pro-poor land reform. Fast-track land reform has not been implemented in line with these principles and we cannot support it.

The Minister for Lands, Land Reform and Resettlement, John Nkomo, had declared five days earlier that all land, from crop fields to wildlife conservancies, would soon become state property. Farmland deeds would be replaced with 99-year leases, while leases for wildlife conservancies would be limited to 25 years.[50] There have since been denials of this policy, however.[51]

Parliament, dominated by ZANU–PF, passed a constitutional amendment, signed into law on 12 September 2005, that nationalised farmland acquired through the "Fast Track" process and deprived original landowners of the right to challenge in court the government's decision to expropriate their land.[52] The Supreme Court of Zimbabwe ruled against legal challenges to this amendment.[53] The case (Campbell v Republic of Zimbabwe) was heard by the SADC Tribunal in 2008, which held that the Zimbabwean government violated the SADC treaty by denying access to the courts and engaging in racial discrimination against white farmers whose lands had been confiscated and that compensation should be paid.[54] However, the High Court refused to register the Tribunal's judgment and ultimately, Zimbabwe withdrew from the Tribunal in August 2009.[55]

In January 2006, Agriculture Minister Joseph Made said Zimbabwe was considering legislation that would compel commercial banks to finance black peasants who had been allocated formerly white-owned farmland in the land reforms. Made warned that banks failing to lend a substantial portion of their income to these farmers would have their licenses withdrawn.

The newly resettled peasants had largely failed to secure loans from commercial banks because they did not have title over the land on which they were resettled, and thus could not use it as collateral. With no security of tenure on the farms, banks have been reluctant to extend loans to the new farmers, many of whom do not have much experience in commercial farming, nor assets to provide alternative collateral for any borrowed money.[56]

Aftermath and outcomes

Land redistribution

The party needs to institute mechanisms to solve the numerous problems emanating from the way the land reform programme was conducted, especially taking cognisance the corrupt and vindictive practices by officers in the Ministry of Lands.

Central Committee Report for the 17th Annual National People's Conference, ZANU–PF[57][58]

Conflicting reports emerged regarding the effects of Mugabe's land reform programme. In February 2000, the African National Congress media liaison department reported that Mugabe had given himself 15 farms, while Simon Muzenda received 13. Cabinet ministers held 160 farms among them, sitting ZANU–PF parliamentarians 150, and the 2,500 war veterans only two. Another 4,500 landless peasants were allocated three.[2] The programme also left another 200,000 farmworkers displaced and homeless, with just under 5% receiving compensation in the form of land expropriated from their ousted employers.[59]

The Institute of Development Studies of the University of Sussex published a report countering that the Zimbabwean economy is recovering and that new business is growing in the rural areas.[60] The study reported that of around 7 million hectares of land redistributed via the land reform (or 20% of Zimbabwe's area), 49.9% of those who received land were rural peasants, 18.3% were "unemployed or in low-paid jobs in regional towns, growth points and mines," 16.5% were civil servants, and 6.7% were of the Zimbabwean working class. Despite the claims by critics of the land reform only benefiting government bureaucrats, only 4.8% of the land went to business people, and 3.7% went to security services.[61] About 5% of the households (not the same as 5% of the land) went to absentee farmers well connected to ZANU-PF. Masvingo is however a part of the country with relatively poor farming land, and it is possible more farms went to "cell-phone farmers" in other parts of the country, according to the study.[62] The study has been criticised for focusing on detailed local cases in one province (Masvingo Province) and ignoring the violent nature of resettlement and aspects of international law.[63] Critics continue to maintain that the primary beneficiaries are Mugabe loyalists.[64]

As of 2011, there were around 300 white farmers remaining in Zimbabwe.[48] In 2018 in the ZANU–PF Central Committee Report for the 17th Annual National People's Conference the government stated that the process of land reform suffered from corruption and "vindictive processes" that needed to be resolved.[57]

After close to two decades, Zimbabwe has started the process of returning land to farmers whose farms were taken over. With the United States demanding the country must return the land before it can lift the sanctions it has imposed on the once flourishing southern Africa country, Zimbabwe began paying compensation to white farmers who lost their farms and the government is actively seeking more participants. In 2020, there are many more than 1000 white farmers tilling the soil, and this number is rising.[65]

On 1 September 2020, Zimbabwe decided to return land that was seized from foreigners between 2000 and 2001; hence, foreign citizens who had their land seized, mostly Dutch, British and German nationals, could apply to get it back. The government also mentioned that black farmers who received land under the controversial land reform program would be moved to allow the former owners "to regain possession".[66]

Impact on production

.jpg.webp)

Before 2000, land-owning farmers had large tracts of land and used economies of scale to raise capital, borrow money when necessary, and purchase modern mechanised farm equipment to increase productivity on their land. Because the primary beneficiaries of the land reform were members of the Government and their families, despite the fact that most had no experience in running a farm, the drop in total farm output has been tremendous and has even produced starvation and famine, according to aid agencies.[7] Export crops have suffered tremendously in this period. Whereas Zimbabwe was the world's sixth-largest producer of tobacco in 2001,[67] in 2005 it produced less than a third the amount produced in 2000.[68]

Zimbabwe was once so rich in agricultural produce that it was dubbed the "bread basket" of Southern Africa, while it is now struggling to feed its own population.[69] About 45 percent of the population is now considered malnourished. Crops for export such as tobacco, coffee and tea have suffered the most under the land reform. Annual production of maize, the main everyday food for Zimbabweans, was reduced by 31% during 2002 to 2012, while annual small grains production was up 163% during the same period.[43] With over a million hectares converted from primarily export crops to primarily maize, production of maize finally reached pre-2001 volume in 2017 under Mnangagwa's "command agriculture" programme.[70]

Tobacco

Land reform caused a collapse in Zimbabwe's tobacco crop, its main agricultural export. In 2001, Zimbabwe was the world's sixth-largest producer of tobacco, behind only China, Brazil, India, the United States and Indonesia.[71] By 2008, tobacco production had collapsed to 48 million kg, just 21% of the amount grown in 2000 and smaller than the crop grown in 1950.[72][73]: 189

In 2005, the contract system was introduced into Zimbabwe. International tobacco companies contracted with small-scale subsistence farmers to buy their crop. In return, the farmers received agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertiliser, as well as advice and supervision.[74][75] Production revived as the small-scale black farmers gained experience in growing tobacco.[76] In 2019, Zimbabwe produced 258 million kg of tobacco, the second-largest crop on record.[77][78] This increase in production came at the cost of quality as the capacity to produce higher-value cured high-nicotine tobacco was lost being largely replaced by lower-value filler-quality tobacco.[79]

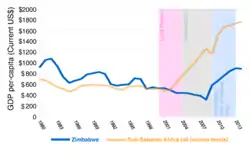

Economic consequences

Critics of the land reforms have contended that they have had a serious detrimental effect on the Zimbabwean economy.[81][6]

The rebound in Zimbabwean GDP following dollarisation is attributable to loans and foreign aid obtained by pledging the country's vast natural resources—including diamonds, gold, and platinum—to foreign powers.[82][83]

In response to what was described as the "fast-track land reform" in Zimbabwe, the United States government put the Zimbabwean government on a credit freeze in 2001 through the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 (specifically Section 4C titled Multilateral Financing Restriction),[84]

Zimbabwe's trade surplus was $322 million in 2001, in 2002 trade deficit was $18 million, to grow rapidly in subsequent years.[85]

References

- SADC newsletter: Eddie Cross interview, see Q2 Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Stiff, Peter (June 2000). Cry Zimbabwe: Independence – Twenty Years On. Johannesburg: Galago Publishing. ISBN 978-1919854021.

- Zimbabwe Country Analysis

- "Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 8 March 2002. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Richardson, Craig J. (2004). The Collapse of Zimbabwe in the Wake of the 2000–2003 Land Reforms. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-6366-0.

- "Zimbabwe won't return land to white farmers: Mnangagwa". Daily Nation. Nairobi, Kenya. Agence France-Presse. 10 February 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018.

- Dancaescu, Nick (2003). "Note: Land reform in Zimbabwe". Florida Journal of International Law. 15: 615–644.

- Chingono, Nyasha (19 November 2019). "The bitter poverty of child sugarcane workers in Zimbabwe". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2013". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "Mugabe's land reform costs Zimbabwe $17 billion: economists". News 24. Cape Town. 12 May 2018. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Kuyedzwa, Crecey (8 April 2019). "White Zim farmers accept R238m interim payment for land compensation". Fin24. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "Zimbabwe agrees to pay $3.5 billion compensation to white farmers". www.msn.com. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Zimbabwe Signs U.S.$3.5 Billion Deal to Compensate White Farmers". allAfrica.com. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Nelson, Harold. Area Handbook for Southern Rhodesia (1975 ed.). American University. pp. 3–16. ASIN B002V93K7S.

- Shoko, Thabona (2007). Karanga Indigenous Religion in Zimbabwe: Health and Well-Being. Oxfordshire: Routledge Books. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-0754658818.

- Alao, Abiodun (2012). Mugabe and the Politics of Security in Zimbabwe. Montreal, Quebec and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 91–101. ISBN 978-0-7735-4044-6.

- "Zimbabwe profile – Timeline". BBC News. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Borstelmann, Thomas (1993). Apartheid's reluctant uncle: The United States and Southern Africa in the early Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 11–28. ISBN 978-0195079425.

- Mosley, Paul (2009). The Settler Economies: Studies in the Economic History of Kenya and Southern Rhodesia 1900–1963. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-0521102452.

-

- Palley, Claire (1966). The Constitutional History and Law of Southern Rhodesia 1888–1965, with Special Reference to Imperial Control (First ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 742–743. OCLC 406157.

- Njoh, Ambeh (2007). Planning Power: Town Planning and Social Control in Colonial Africa. London: UCL Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-1844721603.

- Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 137–153.

- Makura-Paradza, Gaynor Gamuchirai (2010). "Single women, land, and livelihood vulnerability in a communal area in Zimbabwe". Wageningen: Wageningen University and Research Centre. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Maxey, Kees (1975). Fight for Zimbabwe: Armed Conflict in Southern Rhodesia Since UDI. London: Rex Collings Ltd. pp. 102–108. ISBN 978-0901720818.

- Raeburn, Michael (1978). Black Fire! Narratives of Rhodesian Guerrillas. New York: Random House. pp. 189–207. ISBN 978-0394505305.

- Selby, Andy (n.d.). "From Open Season to Royal Game: The Strategic Repositioning of Commercial Farmers Across The Independence Transition in Zimbabwe" (PDF). Oxford: Centre for International Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kriger, Norma (2003). Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe: Symbolic and Violent Politics, 1980–1987. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0521818230.

- Plaut, Martin (22 August 2007). "Africa | US backed Zimbabwe land reform". BBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Online NewsHour – Land Redistribution in Southern Africa: Zimbabwe Program". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Dzimba, John (1998). South Africa's Destabilization of Zimbabwe, 1980–89. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 72–135. ISBN 978-0333713693.

- Laakso, Liisa (1997). Darnolf, Staffan; Laakso, Liisa (eds.). Twenty Years of Independence in Zimbabwe: From Liberation to Authoritarianism. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-0333804537.

- Fisher, J L (2010). Pioneers, settlers, aliens, exiles: the decolonisation of white identity in Zimbabwe. Canberra: ANU E Press. pp. 159–165. ISBN 978-1-921666-14-8.

- Drinkwater, Michael (1991). The State and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe's Communal Areas. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 84–87. ISBN 978-0312053505.

- Dowden, Richard (2010). Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles. London: Portobello Books. pp. 144–151. ISBN 978-1-58648-753-9.

- Selby, Andy (n.d.). "Radical Realignments: The Collapse of the Alliance between White Farmers and the State in Zimbabwe" (PDF). Oxford: Centre for International Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Greste, Peter (15 April 2008). "Africa | Why Mugabe is deaf to the West". BBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Africa | Viewpoint: Kaunda on Mugabe". BBC News. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Majaka, Ndakaziva (3 June 2014). "Bippas won't stop assets seizure: Chinamasa". DailyNews Live. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Country Reports: Zimbabwe at the Crossroads" (PDF). South African Institute of International Affairs. p. 10. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- David McDermott Hughes (12 April 2010). Whiteness in Zimbabwe: Race, Landscape, and the Problem of Belonging. Springer. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-230-10633-8.

In 2000, paramilitaries killed their first white farmer in Virginia, Dave Stevens. More typically, armed groups surrounded farmhouses and harassed their occupants (meanwhile assaulting and often killing black farm workers).

- Meredith, Martin (September 2007) [2002]. Mugabe: Power, Plunder and the Struggle for Zimbabwe. New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 171–175. ISBN 978-1-58648-558-0.

- "Zimbabwes land reform: challenging the myths". The Zimbabwean. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Thornycroft, Peta (24 December 2001). "Evicted farmer sues for return of £2m assets". Telegraph. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Sam Kiley (25 January 2002). "'Britain must act on Zimbabwe' – News – London Evening Standard". Thisislondon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Of securocrats, candles and a raging dictatorship". Thought Leader. 21 August 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Mujuru death 'no accident'". Times LIVE. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Freeman, Colin. "The end of an era for Zimbabwe's last white farmers?". Telegraph. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "The Zimbabwe Situation". The Zimbabwe Situation. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Dixon, Robyn; Thornycroft, Peta (9 June 2004). "Minister Says Zimbabwe Plans to Nationalize Land". Los Angeles Times. Johannesburg and Harare.

- Scoones, Ian (2011). "Zimbabwe's Land Reform: A summary of findings" (PDF). Zimbabweland.net. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 November 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Mike Campbell (Private) Limited v. The Minister of National Security Responsible for Land, Land Reform and Resettlement, Supreme Court of Zimbabwe, 22 January 2008

- Mike Campbell (Pvt) Ltd and Others v Republic of Zimbabwe [2008] SADCT 2 (28 November 2008), SADC Tribunal (SADC)

- "SADC Tribunal Struggles for Legitimacy", Amnesty International USA Web Log, 3 September 2009

- Basildon Peta (10 January 2006). "Harare may force banks to fund black farmers". IOL.co.za. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Kuyedzwa, Crecey (19 December 2018). "Zim government to evict illegal farm settlers". Fin24. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Mugabe, Tendai (17 December 2018). "Corruption, double allocations spoil land reform: Zanu-PF". The Herald. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Brian Raftopoulos & Tyrone Savage (2004). Zimbabwe: Injustice and Political Reconciliation (1 July 2001 ed.). Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. pp. 220–239. ISBN 0-9584794-4-5.

- "Institute of Development Studies: Zimbabwe's land reform ten years on: new study dispels the myths". Ids.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Scoones,Ian; Marongwe, Nelson; Mavedzenge, Blasio; Mahenehene, Jacob; Murimbarimba, Felix; Sukume, Chrispen (2010). Zimbabwe's Land Reform: Myths & Realities. James Currey. p. 272. ISBN 978-1847010247.

- "Zimbabwes land reform: challenging the myths". The Zimbabwean. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Dore, Dale (13 November 2012). "Myths, Reality and The Inconvenient Truth about Zimbabwe's Land Resettlement Programme". Sokwanele. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Robert Mugabe's land reform comes under fresh scrutiny". The Guardian. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- "Over my dead body". Business Insider. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Zimbabwe to return land seized from foreign farmers". BBC News. 1 September 2020.

- "Growing Tobacco" (PDF). Who.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2003. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "afrol News – Tiny tobacco crop spells doom in Zimbabwe". Afrol.com. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "From breadbasket to basket case: Faced with famine, Robert Mugabe orders farmers to stop growing food". The Economist. 27 June 2002.

- "Land reform is a Zimbabwe success story – it will be the basis for economic recovery under Mnangagwa". The Conversation. 29 November 2017.

- "Growing Tobacco" (PDF). Who.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2003. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Marawanyika, Godfrey (4 November 2013). "Mugabe Makes Zimbabwe's Tobacco Farmers Land Grab Winners". Bloomberg.

- Hodder-Williams, Richard (1983). White Farmers in Rhodesia, 1890–1965: A History of the Marandellas District. Springer. ISBN 9781349048953.

- Latham, Brian (30 November 2011). "Mugabe's Seized Farms Boost Profits at British American Tobacco". Bloomberg.

- Kawadza, Sydney (16 June 2016). "Contract farming: Future for agriculture". The Herald (Zimbabwe).

- Polgreen, Lydia (20 July 2012). "In Zimbabwe Land Takeover, a Golden Lining". NYTimes.com. Zimbabwe. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Zimbabwe farmers produce record tobacco crop". The Zimbabwe Mail. 4 September 2019.

- "Tobacco in Zimbabwe". Issues in the Global Tobacco Economy. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2003.

- Raath, Jan (26 October 2015). "The last white farmers of Zimbabwe". Politics Web. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "World Development Indicators". World Bank. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Richardson, Craig J. (2004). The Collapse of Zimbabwe in the Wake of the 2000–2003 Land Reforms. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-6366-0.

- Richardson, Craig J. (2013). "Zimbabwe Why Is One of the World's Least-Free Economies Growing So Fast?" (PDF). Policy Analysis. Cato Institute (722).

- Sikwila, Mike Nyamazana (2013). "Dollarization and the Zimbabwe's Economy". Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies. 5 (6): 398–405. doi:10.22610/jebs.v5i6.414.

- "Full Text of S. 494 (107th): Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001". GovTrack.us. 13 December 2001. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Fao Global Information And Early Warning System on Food And Agriculture – World Food Programme". Fao.org. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

command agriculture program. Government of Zimbabwe 2016

Further reading

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: CPGB-ML (20 December 2010). "Zimbabwe Speaks – Interview with the minister of land reform in Zimbabwe". YouTube. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- Fowale, Tongkeh (30 July 2008). "Zimbabwe and Western Sanctions: Motives and Implications". American Chronicle. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Lebert, Tom (21 January 2003). "Land Research Action Network". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- "Zimbabwe: Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe". Vol. 14, No. 1 (A). Human Rights Watch. March 2002. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Annie Schleicher (14 April 2004). "Zimbabwe's Land Program, PBS Backgrounder". Online NewsHour. Archived from the original on 1 May 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Mugabe and the White African". 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

.jpg.webp)