Zina D. H. Young

Zina Diantha Huntington Young (January 31, 1821 – August 28, 1901) was an American social activist and religious leader who served as the third general president of the Relief Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1888 until her death. She practiced polyandry as the wife of Joseph Smith, and later Brigham Young, each of whom she married while she was still married to her first husband, Henry Jacobs.[2] She is among the most well-documented healers in LDS Church history (male or female), at one point performing hundreds of washing, anointing, and sealing healing rituals every year.[3] Young was also known for speaking in tongues and prophesying. She learned midwifery as a young girl and later made contributions to the healthcare industry in Utah Territory, including assisting in the organization of the Deseret Hospital and establishing a nursing school. Young was also involved in the women's suffrage movement, attending the National Woman Suffrage Association and serving as the vice president of the Utah chapter of the National Council of Women.

| Zina D. H. Young | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Relief Society General President | |

| April 8, 1888 – August 28, 1901[1] | |

| Called by | Wilford Woodruff |

| Predecessor | Eliza R. Snow |

| Successor | Bathsheba W. Smith |

| First Counselor in the Relief Society General Presidency | |

| June 19, 1880 – April 1888[1] | |

| Called by | Eliza R. Snow |

| Predecessor | Sarah M. Cleveland |

| Successor | Jane S. Richards |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Zina Diantha Huntington January 31, 1821 Watertown, New York, United States |

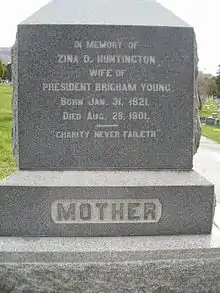

| Died | August 28, 1901 (aged 80) Salt Lake City, Utah, United States |

| Resting place | Salt Lake City Cemetery 40.7772°N 111.8580°W |

| Spouse(s) | Henry B. Jacobs Joseph Smith Brigham Young |

| Children | 3, plus 4 adopted |

| Parents | William Huntington Zina Baker |

Family and conversion

Zina Huntington was born on January 31, 1821,[4]: 87 in Watertown, New York, the eighth child of William Huntington and Zina Baker.[5] She had nine siblings.[6]: 443 Her father's family was descended from Puritan Simon Huntington, who died at sea in 1633 on the voyage to America. Her father was a veteran of the War of 1812; her grandfather a soldier in the Revolutionary War;[7] and his brother, Samuel Huntington, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[8] As a young girl, she was taught household skills, such as spinning, soap making, and weaving,[9] and received a basic education. She developed musical talent by learning to play the cello.

Religion had always been important to her parents, and, as a youth during the Great Awakening, Zina Huntington grew up in a home where matters of spiritual importance were consistently included in the family dialogue.[10]: 86 Her parents had long been searching for a church they believed to be true when,[6]: 455 in 1835, her family was contacted by Hyrum Smith and David Whitmer, missionaries of the then Church of the Latter Day Saints. With the exception of her oldest brother, the entire family joined the church. Zina was baptized by Smith on August 1, 1835, at the age of fourteen.[7] She was then confirmed by Smith and Whitmer, after which she recorded speaking in tongues.[6]: 452

In October 1836,[9] after receiving advice from Joseph Smith, Sr., Zina's father sold their property and relocated to the church's headquarters in Kirtland, Ohio. There, she participated as a member of the Kirtland Temple Choir.[7] Nineteen months later, the family moved again to Far West, Missouri. They arrived in Far West at a time of violence between Missouri residents and the newly arrived Mormons. After Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs issued the Extermination Order, Zina's father helped coordinate the evacuation of church members to Illinois. The Huntington family arrived in Illinois in Spring 1839. Though healthy upon their arrival, eighteen-year-old Zina and her mother both fell ill that summer in a malaria epidemic in Nauvoo. Her mother died, but Zina recovered after receiving care in the home of Joseph and Emma Smith.[10] The former had tasked his daughter, Julia, with taking care of young Zina Huntington. She grew close to the Smith family as a result.[9] In her mother's absence, she took on the role of caring for her father and siblings. Her father died when the Mormons were forced to leave Nauvoo. Before the forced departure, Zina Huntington received her endowment in the Nauvoo Temple. She also joined the Relief Society at its first-ever meeting on March 24, 1842.[6]: 444, 457–58

Spiritual gifts

Young was noted among the new converts of the church for her somewhat remarkable spiritual gifts. Not long after her family arrived in Kirtland, she exhibited the gift of tongues and of the interpretation of tongues,[11] gifts she continued to demonstrate throughout her life.[7] She also later exhibited the gifts of prophecy and healing.[12]: 126 Emmeline B. Wells later wrote of her: "In all spiritual labors and manifestations, she was greatly gifted, and no woman in Israel was more inspirational in prayer .... Her whole life was one of untiring devotion to her Heavenly Father."[13]: 46

As General Relief Society President, Young traveled throughout the church performing hundreds of healing blessings every year; she is possibly the LDS Church's most well documented healer, male or female.[3] Though healing rituals are strictly a function of the male priesthood in the contemporary Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, up through the presidency of Joseph F. Smith, female healing blessings were part of the orthodoxy.[3] Young would carefully wash, anoint, and seal healing blessings, even in the presence of her husband Brigham Young and other church leaders.[3] She taught and encouraged other women to heal as well, preaching at the 1889 General Relief Society Conference, "it is the privilege of all Sisters living as they should to administer the ordinances to their Sisters in sickness & the little ones in faith & humility."[14] She earned the name "Zina, the comforter",[6]: 446 particularly after tending to the sick during the journey west as a Mormon pioneer.[9]

Marriages and children

Young recorded in her autobiography that she was courted by Henry Bailey Jacobs when she was eighteen years old. During this time, Joseph Smith also taught her about plural marriage in private conversations; he proposed that she become his plural wife on at least three different occasions.[10]: 90 [15]: 77–79 Young declined the proposals out of her respect for Emma Smith and for traditional Christian monogamy, and because such a union would require secrecy.[10]: 90 On March 7, 1841, she married Jacobs, believing she had thus avoided future proposals from Smith.[10]: 93 Nauvoo mayor John C. Bennett conducted the ceremony. Her journal from the day of the wedding reads:

I was Married to Mr. Henry Bailey Jacobs. He had been a missionary preaching the Gospel for some time. His Father Henry Jacobs was one of the first elders in the Church, faithful and true until the last.[10]: 94

Young became pregnant shortly after her marriage. However, she continued to feel concern that she had rejected God by rejecting Joseph, whom she considered a prophet and God's spokesperson. She later recorded, "I received a testimony for myself from the Lord of this work, and that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God before I ever saw him, while I resided in the state of New York, given in answer to prayer. I knew him in his lifetime, and know him to have been a great true man and a servant of God."[10]: 94 Smith wrote to her in October 1841 that he had "put it off till an angel with a drawn sword stood by me and told me if I did not establish that principle [plurality of wives] upon the earth I would lose my position and my life."[10]: 95 [15]: 80–81 [16] She and Smith were married on October 27, 1841.[15]: 81–82 [17] Her brother Dimick performed the ceremony. By that time, Joseph was married to six other women: Emma Smith, Fanny Alger, Louisa Beaman, Lucinda Pendleton Morgan, Nancy Marinda Johnson Hyde, and Clarissa Reed Hancock.[10]: 96

Young was about seven months pregnant with Jacobs' child (Zebulon William Jacobs), as confirmed by DNA evidence,[18] when she married Smith.[19] It is not clear when Jacobs was made aware of the wedding to Smith; he did, however, believe in Smith's prophetic counsel.[10] Zina and Henry Jacobs continued to live together as man and wife,[15]: 81–82 and her "connubial relations with Joseph Smith, if any occurred at all, [were] certainly infrequent and irregular."[10]: 104 She never had any children with Smith, but she and Jacobs had another son, Henry Chariton Jacobs, on March 22, 1846. Her husband Henry was constantly called on missions (he served at least eight between 1839 and 1845)[12]: 177 and was thus often absent from the house. In the face of such absences, Zina did not turn to Smith but rather sought relief from female kin. Her marriage to Henry, riddled with absences as it was, was the only time in her life that she would have a full-time husband.[12] Though many 19th- and early 20th-century Mormon biographers painted her marriage to Henry as "not proving a happy union"[11]: 33 to justify her subsequent marriages to Smith and later to Brigham Young, evidence from her diaries suggests this assertion is unfounded.[15]: 81

After Smith's death in 1844, Jacobs stood by while Young was sealed to Smith in the Nauvoo Temple.[19] Later in life, she called herself Joseph's "widow".[7]: 698 She was present at the meeting in which Brigham Young was chosen to lead the church; later, she and others recounted that Young spoke with the voice and appearance of Smith on that occasion.[20] Because she believed him to be God's chosen leader, she consented when Young, 20 years her senior, claimed he acted as Smith's proxy and proposed they be married for time (as many other members of the Quorum of the Twelve did with Smith's other plural wives). Brigham was united "for time" with Zina on February 2, 1846, and, at the same time, she was re-sealed to Smith for eternity.[10]: 103 Some scholars argue that at this point, Brigham Young and other church leaders considered her civil marriage to Jacobs canceled, superseded by the spiritual marriages, though no formal divorce was ever documented.[10] Over a decade later, Brigham would explain, "There was another way—in which a woman could leave a man—if the woman preferred—another man higher in authority and he is willing to take her. And her husband gives her up—there is no Bill of divorce required in the case it is right in the sight of God."[10] In May 1846, Young called Henry Jacobs to serve a mission to England. In August 1846, Zina's father died, and Zina took shelter in the household of Brigham Young.[15] : 84, 88, 89–91 [21] Biographer Todd Compton believed that this move supported the interpretation that Zina at this time "began to live openly as Brigham's wife".[15] : 90 [21] However it was not until six months after the return of Henry Jacobs that Zina conceived a child with Young, a daughter named Zina Presendia Young, born in 1850.[2] What is certain is that Henry Jacobs, upon his return, was brought before a church council for his role in performing marriages uniting multiple women to William W. Phelps in England without authorization. Phelps was excommunicated. Henry was "silenced" for performing the marriages. "It was decided in Council that if a man lost his wife He was at liberty to marry again whare He pleased and was Justifyed."[15] : 92 [21] The Council clearly considered at this time that Henry Jacobs's marriage to Zina was now over.

Jacobs struggled with this judgment, feeling that Zina should have remained his wife. In later years Jacob wrote to Zina: "the same affection is there .... But I feel alone .... I do not Blame Eny person .... [M]ay the Lord our Father bless Brother Brigham .... [A]ll is right according to the Law of the Celestial Kingdom of our God Joseph".[15] : 81–82

Zina Young joined the Mormon Exodus to the Rocky Mountains,[22] arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in September 1848. In Utah Territory, she would raise her two sons from Jacobs, her daughter, and the four children of Brigham Young and Clarissa Maria Ross Young, her sister-wife who had died unexpectedly.[6]: 444 She resisted the loss of her independence as Brigham drew her, physically and socially, into his vast household, and found herself very lonely once there.[4]: 87–89 She relied heavily upon kinship ties to her brothers and sister for the rest of her life.

Relationship to polygamy

In order to understand Young's decisions regarding plural marriage, it is pivotal to examine her relationship to the practice of polygamy. Though initially she struggled to understand the morality of the practice, she came to accept it—not because she found virtue in the practice itself, but because it came from Joseph Smith, and he was the prophet. Her "unwavering obedience and unquestioning faith" ultimately determined her decision to be married to Smith and later to Brigham Young.[12]: 128 To her, the decision became a test of the integrity she would show to her faith; she later wrote in her journal, "could I compromise conscience ... lay aside the sure testimony of the Spirit of God for the Glory of this world?".[10] This principle of total obedience and submission to church leaders she regarded as prophets came to define her faith. In her last conference of the Relief Society in October 1900 in the Salt Lake Assembly Hall, Zina Young advised, "Sisters, never speak a word against the authorities of this church."[13]

In time, Young accepted polygamy as a lifestyle. On one occasion, she proclaimed: "The principle of plural marriage is honorable. It is a principle of the gods, it is heaven born. God revealed it to us as a saving principle: we have accepted it as such and we know it is of him, for the fruits of it are holy.... We are proud of the principle because we know its true worth."[7]: 698 In 1890, when church president Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto that led to the end of the practice of polygamy in the church, Young lamented, "Today the hearts of all were tried but looked to God and submitted."[23]

In later life, Zina Young commented that women in polygamous relationships "expect too much attention from the husband and ... become sullen and morose". She explained that "a successful polygamous wife must regard her husband with indifference, and with no other feeling than that of reverence, for love we regard as a false sentiment; a feeling which should have no existence in polygamy".[15] : 108, 466–67 She came to rely primarily on relationships with kin and other women in the community for support and friendship.

Civic leadership and church service

Contributions to public health

In Utah, once her children were grown, Young became involved in a number of public service activities. She became a school teacher and studied obstetrics under Willard Richards. As a midwife (she had learned midwifery from her mother in New York) she "helped deliver the babies of many women, including those of the plural wives of Brigham Young. At their request, she anointed and blessed many of these sisters before their deliveries. Other women in need of physical and emotional comfort also received blessings under her hands."[1]: 654 In 1848, Young enrolled in classes in herbal medicine and home nursing as well, seeking to increase her contributions to healthcare in Utah.[9] In 1872, she helped establish the Deseret Hospital in Salt Lake City, and served on its board of directors and for twelve years as its president. She also organized a nursing school and taught courses in obstetrics.[9]

Women's suffrage

Young was active in the temperance and women's suffrage movements, and, in the winter of 1881–82, attended the Women's Conference in Buffalo and a National Woman Suffrage Association convention in New York.[5]

Church service

After the LDS Church's Relief Society was reorganized church-wide in 1868,[6]: 460 Young was selected as first counselor by President Eliza R. Snow.[7] The new general presidency was active in refining the society's organization and functions, and helped develop additional church auxiliaries, including the Young Ladies' Retrenchment Association and the Primary Association. Young was seen as complementary to Snow; it was later remarked that "Sister Snow was keenly intellectual, and she led by force of that intelligence. Sister Zina was all love and sympathy, and drew people after her by reason of that tenderness."[9] The two grew close through their service together in the Relief Society General Presidency; they worked together on projects such as the Deseret Hospital, silk manufacture, and grain storage. They also spoke at church meetings together throughout Utah.[6]: 460 In addition to Snow, Young counted other prominent women in the Relief Society as her friends, including Bathsheba Smith and Emmeline B. Wells.[24]: 197

Though she harbored a fear of worms, Young took charge of the Relief Society's sericulture (silk-producing) initiative, becoming president of the Deseret Silk Association in 1875 and the Utah Silk Commission in 1896.[6]: 446

At the request of the Relief Society, Young wrote a short autobiography to put in a time capsule as a part of the 1880 Church Jubilee Celebration. The capsule was opened 50 years later, in 1930.[6]: 454 She also wrote an article describing her religious experiences entitled "How I Gained My Testimony" for the Young Woman's Journal. Young was a staunch supporter of the Young Ladies' Mutual Improvement Association, the forerunner to the church's Young Women's program.[6]: 447

As a leader among women, she was known for her nurturing character. She embraced the "feminine sphere" of her time, spending her life in Utah serving and influencing other women. Her "hallmark was intimate care: nursing, midwifery, attendance at the sickbed, radiance in the blessing circle, and powerful spirituality as she spoke in or interpreted tongues".[24]: 215

When Snow died in 1887,[7] Young became Relief Society General President, a position she held for thirteen years. In this capacity, she organized the first Relief Society General Conference; and, during the years of her presidency, the construction of the Salt Lake Temple was completed, women in Utah regained the right to vote, and the Relief Society was featured in the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.[6]: 460–61 She served for a total of 32 years on the Relief Society General Board.[9]

In 1891, she became vice president of the National Council of Women.[7] She worked in the Endowment House, and became the first matron of the Salt Lake Temple from 1893, a position she held until her death.[6]: 444–45

Death and legacy

Zina D. H. Young died on August 28, 1901, at age 80.[9] She spent the last two months of her life in Canada with her daughter and grandchildren.[6]: 447

The legacy of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs Smith Young is one of obedience, diligence, and service. She was a member of a well-known circle of early Latter Day Saints, having been sealed to two presidents of the church and serving as a leader of Mormon women in Utah.[4]: 88 Her tender nature towards Utah women led many to call her "Aunt Zina". Of her, Susa Young Gates wrote: "There have been many noble women, some great women and a multitude of good women associated, past and present, with the Latter-Day work. But of them all none was so lovely, so lovable, and so passionately beloved as was 'Aunt Zina.'"[9] Above all, her legacy is the strength she found in communities of women where she found "the Spirit of God is, and when we speak to one another, it is like oil going from vessel to vessel."[25]

References

- Ludlow, Daniel H, ed. (1992). "Appendix 1: Biographical Register of General Church Officers". Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. p. 1651. ISBN 9780028796055. OCLC 24502140.

- Allen L. Wyatt (August 2006). "Zina and Her Men: An Examination of the Changing Marital State of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs Smith Young". 2006 FAIR Conference. FairMormon. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Stapley, J. A. (2018). The power of godliness: Mormon liturgy and cosmology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. page 79

- Higbee, Marilyn (1993). ""A Weary Traveler": The 1848–50 Diary of Zina D. H. Young". Journal of Mormon History. 19 (2): 86–126. JSTOR 23286376 – via JSTOR.

- Woodward, Mary Firmage (1992). Ludlow, Daniel H. (ed.). "Young, Zina D. H." Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780028796055.

- Reeder, Jennifer (2012). "'Power for the Accomplishment of Greater Good': Zina Diantha Huntington Young". In Turley, Richard E.; Chapman, Brittany A. (eds.). Women of Faith in the Latter Days. Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book. pp. 443–463. ISBN 978-1-60907-173-8.

- Jenson, Andrew (1941). "Zina Diantha Huntington Young". Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: Deseret News. 1: 697–699. ISBN 9781589580312.

- Whitney, Orson F. "Zina Huntington Young." History of Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah : G. Q. Cannon & Sons Co, 1892. 576–578. Print. Page 576.

- Black, Susan Easton; Woodger, Mary Jane (2011). Women of Character: Profiles of 100 prominent LDS Women. American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications. pp. 377–79. ISBN 9781680470185.

- Bradley, Martha Sonntag; Woodward, Mary Brown Firmage (1994). "Plurality, Patriarchy, and the Priestess: Zina D. H. Young's Nauvoo Marriages". Journal of Mormon History. 20 (1): 84–119. JSTOR 23286315.

- Crockwell, James H (1887). Pictures and Biographies of Brigham Young and his Wives. Salt Lake City, Utah.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach (1993). "Each in Her Own Time: Four Zinas" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 26 (2): 119–135. doi:10.2307/45228588. JSTOR 45228588. S2CID 254338652.

- Wells, Emmeline B. (1901). "Zina D. H. Young:A Character Sketch". Improvement Era. 5 (1): 43–48.

- Stapley, J. A. (2018). The power of godliness: Mormon liturgy and cosmology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. page 93

- Compton, Todd (1997). In Sacred Loneliness. pp. 77–91, 108, 466–467.

- Zina Young, "Joseph the Prophet His Life and His Mission as Viewed By Intimate Acquaintances", Salt Lake Herald Church and Farm Supplement, January 12, 1895.

- Bushman 2005, pp. 439–40; Brodie 1971, pp. 465–66; Quinn 1994, pp. 633.

- Perego, Myers & Woodward 2005.

- Brodie 1971, p. 465.

- Firmage, Mary Brown. "Great-Grandmother Zina: A More Personal Portrait," Ensign, March 1984.

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1989). Mormon Polygamy: A History. Signature Books. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780941214797.

- Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach (1979). "All things move in order in the city: The Nauvoo diary of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs". BYU Studies. 19 (3): 285–320.

- "The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage". LDS Church.

- Bradley, Martha Sonntag; Firmage Woodward, Mary Brown (2000). 4 Zinas: A Story of Mothers and Daughters on the Mormon Frontier. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 9781560851417.

- Madsen, Carol Cornwall (1994). In Their Own Words: Women and the Story of Nauvoo. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book. p. 30. ISBN 9780875797700.

Further reading

- Allen, James B.; Leonard, Glen M. (1976), The Story of the Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, ISBN 0-87747-594-6

- Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach, ed. (Spring 1979), "All Things Move in Order in the City: the Nauvoo Diary of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs", BYU Studies, 19 (3): 285–320

- Bradley, Martha Sonntag; Woodward, Mary Brown Firmage (1994), "Plurality, Patriarchy, and the Priestess: Zina D. H. Young's Nauvoo Marriages", Journal of Mormon History, 20 (1): 84–118, JSTOR 23286315.

- Bradley, Martha Sonntag; Woodward, Mary Brown Firmage (2000), Four Zinas: A Story of Mothers and Daughters on the Mormon Frontier, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-141-4

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971), No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd ed.), New York: Knopf, ISBN 0-394-46967-4

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005), Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, New York: Knopf, ISBN 1-4000-4270-4

- Compton, Todd (1997), In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-085-X

- Higbee, Marilyn, ed. (Fall 1993), "'A Weary Traveller': The 1848-1850 Diary of Zina D. H. Young", Journal of Mormon History, 19 (2): 86–125

- Ludlow, Daniel H., ed. (1992), Church History: Selections from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Deseret Book, ISBN 0-87579-924-8

- Moore, Carrie A. (May 28, 2005). "Research focuses on Smith family". Deseret Morning News. Deseret News. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- Peterson, Janet; Gaunt, LaRene (1990), Elect Ladies: Presidents of the Relief Society, Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book, ISBN 0-87579-416-5

- Perego, Ugo A.; Myers, Natalie M.; Woodward, Scott R. (2005), "Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith, Jr: Genealogical Applications", Journal of Mormon History, 32 (2): 70–88

- Quinn, D. Michael (1994), The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-056-6

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1989), Mormon Polygamy: A History, Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, ISBN 978-0-941214-79-7.

External links

- Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs Smith Young papers, Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library, L. Tom Perry Special Collections

- Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs Smith Young letter, Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library, L. Tom Perry Special Collections