Zinc sulfate (medical use)

Zinc sulfate is used medically as a dietary supplement.[1] Specifically it is used to treat zinc deficiency and to prevent the condition in those at high risk.[1] This includes use together with oral rehydration therapy for children who have diarrhea.[2] General use is not recommended.[1] It may be taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[1]

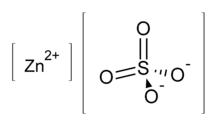

Chemical model | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | zink SUL fate |

| Trade names | Solvazinc, Micro-Zn, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Trace element |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | O4SZn |

| Molar mass | 161.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Side effects may include abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, and feeling tired.[2] While normal doses are deemed safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding, the safety of larger doses is unclear.[3] Greater care should be taken in those with kidney problems.[2] Zinc is an essential mineral in people as well as other animals.[4]

The medical use of zinc sulfate began as early as the 1600s.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6][7] Zinc sulfate is available as a generic medication.[8] and over the counter.[1][3]

Medical uses

The use of zinc sulfate supplements together with oral rehydration therapy decreases the number of bowel movements and the time until the diarrhea stops.[2] Its use in this situation is recommended by the World Health Organization.[2]

There is some evidence zinc is effective in reducing hepatic and neurological symptoms of Wilson's disease.[9]

Zinc sulfate is also an important part of parenteral nutrition.[1]

Misuse

During the 1918 flu pandemic in New Zealand, inhalation chambers were set up in towns and cities as a means to boost immunity. The public were encouraged to attend these chambers and inhale a zinc sulfate mist, a process that was said to disinfect the lungs and throat and protect against infection. In reality, the inhalation of hot steam could inflame the nasal tissue, potentially making participants more susceptible to infection.[10]

In towns such as Ashburton, New Zealand for example, in order to be eligible to travel by train, people had to present documentation at the train station proving that they had been through the inhalation chamber.[11]

The inhalation chamber which was set up in the old Dunedin Post Office building was described as follows: "It was a small room, relatively airtight, holding 20 or 30 persons, and the air is impregnated with the vapour of zinc sulphate. Each batch remains in the chamber for 10 minutes, and the persons treated are instructed to breathe through the nose at first, and then through the mouth."[12]

References

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 700. ISBN 9780857111562.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 349–51. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- "Zinc sulfate Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 9 December 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- National Research Council; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Committee on Minerals and Toxic Substances in Diets and Water for Animals (2006). Mineral Tolerance of Animals: Second Revised Edition, 2005. National Academies Press. p. 420. ISBN 9780309096546. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- Sneader W (2005). "Chemical Medicines". Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 62. ISBN 9780471899792. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Appenzeller-Herzog C, Mathes T, Heeres ML, Weiss KH, Houwen RH, Ewald H (November 2019). "Comparative effectiveness of common therapies for Wilson disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies". Liver International. 39 (11): 2136–2152. doi:10.1111/liv.14179. PMID 31206982. S2CID 190530360.

- "Inhalation". New Zealand Geographic. New Zealand Geographic.

- "Increase at Ashburton Guardian,". Ashburton Guardian. National Library of New Zealand. 14 November 1918. p. 4.

- "Inhaling Influenza". Toitu Otago Settlers Museum. Toitu Otago Settlers Museum.

External links

- "Zinc Sulfate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.