Schoemansdal, Limpopo

Schoemansdal (Dutch for Schoeman's dale; at first Oude Dorp and Zoutpansbergdorp) was a settlement situated 16 km west of Louis Trichardt (Makhado), which had its origins during the Great Trek. It existed from 1848 to 1867, and functioned as the capital of an autonomous region until the S.A.R. Volksraad was established, when the outpost came under the supervision and regulations of the central government.[1] The settlement was evacuated after only thirty years when attacked by Venda militants. The government rendered indecisive support and the town as torched by Katze-Katze on the night of 15 July 1867.[2]

Schoemansdal

"Zoutpansbergdorp" "Oude Dorp" | |

|---|---|

Schoemansdal  Schoemansdal | |

| Coordinates: 23°03′09″S 29°46′12″E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Limpopo |

| District | Vhembe |

| Municipality | Makhado |

| Established | 1848 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| PO box | 1331 |

| |

After the S.A.R. reestablished control over the area in 1898, the former settlement was ignored and a new one started, at the present Louis Trichardt. Consequently Schoemansdal was the only Voortrekker settlement not to evolve into a modern town. The archaeological site with traces of the former settlement is currently state property and access is controlled. It is situated on the north bank of the Dorps River at 552 m.a.s.l., near present-day Hamantsha and Tshiozwi townships and the Schoemansdal railway siding.

Early Voortrekkers

The earliest western visitors to the area after the renegade Coenraad de Buys, were the Voortrekker parties led by Hans van Rensburg and Louis Tregardt. They arrived separately at the Zoutpansberg in 1836, after parting ways over an earlier disagreement. Van Rensburg headed east towards Inhambane but his entire party was exterminated en route. Tregardt stayed at the Salt Pan from May to August 1836 and arrived at the site of future Schoemansdal on 3 November 1836. They stayed about two weeks, but resided in the general vicinity for more than a year. After reconnaissance missions into the current Zimbabwe and eastwards into current Mozambique in search of the Van Rensburg clan, they made Delagoa Bay their destination, away from British influence. They started on their epic journey in September 1837 and reached Delagoa Bay seven months later. The trek exacted a high toll; 27 of 53 persons perished from malaria, including Tregardt.

Zoutpansbergdorp

Eleven years after Tregardt's departure, a settlement named Oude Dorp was established at Tregardt's earlier camp. It was founded by field cornet Jan Valentyn Botha[3][4] who led a faction of Andries Potgieter's trek, consisting of about 48 families.[5] When their wagon train arrived on 2 May 1848 from Andries-Ohrigstad, they immediately constructed an earthen redoubt (or schans) and reed-huts (or scherms).[6] Potgieter, who headed the earlier reconnaissance mission over the Limpopo river, arrived subsequently from Ohrigstad where his followers were being decimated by malaria. He was of the opinion that the Zoutpansberg was sufficiently distant from British influence to afford the possibility of independence, and chose the location as the capital of his republic. The town was henceforth named Zoutpansberg (dorp).

The settlement had a promising start. Portuguese traders opened trading stores and the ivory trade blossomed. Rice and wheat croplands, fruit orchards and coffee plantations were established. The town also traded in salt, game and ostrich skins, ostrich feathers, animal horns and wood.[5][7] Wood used for trading or construction included yellowwood, tamboti and beech wood.[5]

Potgieter enjoyed independence in this northern outpost and ruled over extensive territory. He and his followers opposed the notion of a Volksraad for the Overvaal region, besides any relations with Cape colonial authorities.[8] In 1849, the Voortrekker faction led by J. J. Burger that remained in Ohrigstad (and subsequently Lydenburg) engaged in a series of negotiations with the faction headed by Andries Pretorius in Potchefstroom. After meetings at Hekpoort, Olifants River and Derdepoort respectively, an Overvaal Volksraad was constituted. Potgieter at first refused to accept its authority but relented when faced with an embargo.[8] Potgieter rendered no assistance to the Transoranje Voortrekkers when their republic was annexed by Britain in 1848. He died at Zoutpansbergdorp in 1852, months after Andries Pretorius negotiated the independence of the Overvaal with British authorities. He left his son, cmdt.genl. Piet Potgieter, in charge of the town.

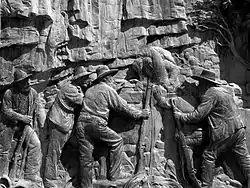

In September 1854 Piet's uncle, field cornet Hermanus Potgieter (Groot Hermaans), was searching for ivory near the Nyl River, an area ruled by chiefs Makapan and Mankopane (also: Mapela or Mapele). For reasons imperfectly known, the chiefs decided to massacre them and other unrelated white travellers. The act claimed the lives of 28 white settlers,[9] and the Potchefstroom governance authorized a punitive commando under the command of Piet Potgieter and M. W. Pretorius. The tribesmen retreated into Makapansgat cave, where they were to suffer heavy casualties. One of their snipers, however, managed to fatally shoot Piet Potgieter.[10] This was the only Boer casualty of the campaign, but his death brought an end to the Potgieters' hegemony in the north.

Schoemansdal

By 1855, the town's de facto leader was cmdt.genl. Stephanus Schoeman.[4] He renamed the growing, although disorderly reed-hut settlement Schoemansdal, after himself, had it surveyed and divided into equal erven.[6] Augmented by renegades, the town was now a successful ivory trading centre, and its population numbered a few hundred (1,800 according to one estimate). During this year it was also visited by Deocleciano Das Neves and Pastor Joaquim de S. R. Montanha from Portuguese ports on the east coast. Reverends Andrew Murray, J. H. Neethling, Piet Huet and Dirk van der Hoff were visiting clergy before a permanent minister took residence.

With the arrival of a resident minister, reverend N. J. van Warmelo in 1864, and that of the first teacher, Cornelia van Boeschoten, in 1866, the community had an air of permanence. In addition Joao Albasini, Augusto Carvalho, Cassimiro Simmoens and Dietlof Maré had established shops in the town. Besides reed huts, there were now some structures of raw or burnt clay bricks which indicated that their owners were determined to settle permanently. The church building was the first of its kind in the Zoutpansberg, and during the week it served as the school building.[5] The parsonage was a high quality building, which was initially built to house Schoeman.

Professional medical services were however unavailable, and the residents relied on home remedies.[5] Many died of yellow fever or malaria. Over-hunting had a devastating effect on the animal populations and the Pretoria government reacted in 1858 by placing limits on the trade in animal products.[11] This was hardly enforceable as the town had become a refuge for increasingly lawless ivory hunters and traders. Arms smuggling was rampant and at one point 30 tons of lead was imported for manufacturing of bullets.[8] Venda hunters, or so-called swart skuts, supplied the Voortrekkers with ivory and were in turn supplied with firearms. Relations between the Voortrekkers and Venda soured owing to taxation (called opgaaf), cattle rustling and lax control over firearms.[4]

Hostilities and demise

Total discord broke out in 1866, after the Voortrekkers had intervened in khosi Ramabulana's succession dispute,[11] and one claimant, his youngest son Makhado (also: Makhato or Magato), attacked and torched an outlying Voortrekker settlement.[3] The town residents moved to the redoubt at the center of town for safety.

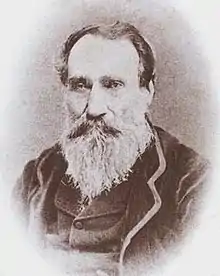

The next year Paul Kruger was sent from Pretoria with some 400 to 500 men to restore law and order. Discipline in the ranks of Kruger's relief commando was however poor and they were furnished with very limited ammunition. On reaching Schoemansdal, which was under threat by chief Katze-Katze (also: Katlakter), Kruger and his officers resolved that holding the town was impossible and ordered a general evacuation. The Voortrekkers abandoned the town on 15 July 1867[4] and established Pietersburg.

Following its abandonment Katze-Katze razed the town. The loss of Schoemansdal, once a prosperous settlement by Boer standards, was considered a great humiliation by many burghers. The Transvaal government formally exonerated Kruger over the matter, ruling that he had been forced to evacuate Schoemansdal by factors beyond his control, but some still argued that he had given the town up too readily.[12] Peace returned to Zoutpansberg in 1869, following the intervention of the republic's Swazi allies.[13] After its razing, Schoemansdal was never rebuilt and all that remained was its graveyard,[14] irrigation systems and roads.[7]

Layout

First settlement

Families in the first settlement, Zoutpansbergdorp, lived exclusively in hartbeeshuise (etymology perhaps "hard-reed house"), which were elongate, pitched-roof shelters built directly on the ground, with or without internal partitions. These were constructed of wooden poles and laths, with the spaces between the laths plastered over or filled in with reeds, which were obtained from a large reed marsh in the Dorps River.[15]

Pastor Joaquim de S.R. Montanha who visited the settlement in 1855 on behalf of the governor in Inhambane reported that some small houses were occupied by more than one, or even several families.[16] Windows were merely holes above the reed door, which according to Montanha were closed off with hessian fabric.

Second settlement

Construction of a second redoubt preceded the town of Schoeman's day. It was constructed of raw and burnt clay bricks, with cannons stationed on two bastions and loopholes in the walls. The subsequent market square, parsonage and church were in its immediate vicinity. Das Neves estimated that there were never more than 70 houses, though excavations at the site suggest a higher number.[5] The town had a rectangular layout and all erven were of the same size. Fountain and stream water was channeled to town in two furrows, one of them 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) long.[5]

Recent developments

The Transvaal Provincial Museum Service began excavations in 1985. Reports of the partial excavations are housed in the museum offices at Louis Trichardt. During 1989 experimental reconstructions were made of some shelters, to the south of the archaeological site. An open-air museum was established which managed an area of 600 ha,[5] but its information centre burnt down in 2008, and some irreplaceable items were lost.[7]

See also

References

- Sacred Traditions and Biodiversity Conservation in the Forest Montane Region of Venda, South Africa. Clark University: ProQuest. 2008. p. 74. ISBN 9780549518686.

- Hilton-Barber, Bridget (2001). Weekends with legends (1st ed.). Claremont [South Africa]: Spearhead. p. 14. ISBN 9780864864710.

- Knight, Ian; Embleton, Gerry (1996). The Boer Wars (1): 1836-98. Osprey Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 1-85532-612-4.

- Hopkins, Pat (2006). Ghosts of South Africa. Zebra. pp. 75–76. ISBN 1-77007-303-5.

- Küsel, Dr. Udo S. "Schoemansdal archaeological site management plan" (PDF). limpopo.gov.za. African Heritage Consultants. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Rademeyer, Jacobus Ignatius. "Die Oorlog teen Magato (M'pefu) 1898" (PDF). repository.up.ac.za. M. A. dissertation, University of Pretoria. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "Schoemansdal, Soutpansberg, Limpopo". showme. 30 January 2013.

- "Die Eerste Gesamentlike Vergadering van die ZAR se Volksraad in 1849 (The first joint meeting of the ZAR Volksraad in 1849)". toxinews.blogspot.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Site 9/2/257/0001". SAHRA. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Geskiedenis van Makapansgat" (PDF). solidariteit.co.za. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Braun, Lindsay F. (2014). Colonial Survey and Native Landscapes in Rural South Africa, 1850 - 1913: The Politics of Divided Space in the Cape and Transvaal (revised ed.). BRILL. pp. 252–255. ISBN 9789004282292.

- Meintjes, Johannes (1974). President Paul Kruger: A Biography (First ed.). London: Cassell. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-304-29423-7.

- Davenport, T. R. H. (2004). "Kruger, Stephanus Johannes Paulus [Paul] (1825–1904)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41290.

- Op Pad in Suid-Afrika. B. P. J. Erasmus, 1995, ISBN 1-86842-026-4

- Nathan, Manfred (1941). Paul Kruger: His life and times. Durban: Knox. p. 101.

- Montanha, Pater J. de S. R. (1857). "Transvaalse Argiefbewaarplek, Pretoria: A 81" (PDF). p. 10.