2012 outbreak of Salmonella

The 2012 outbreak of Salmonella took place in 15 places worldwide with over 2,300 strains identified.

In general, the United States alone experiences 1 million cases of salmonellosis per year.[1] In Europe, although there are around 100,000 incidents of salmonellosis reported annually, there has been a steady decrease in cases over the past four years.[2] The exact number of those infected is impossible to know as not all cases are reported. Of these reported cases, some can be classified as foodborne disease outbreaks by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) if "two or more people get the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink"[3] or zoonotic outbreaks if "two or more people get the same illness from the same pet or other animal".[4] In 2012, the various strains or serotypes of the Salmonella bacteria, related to the outbreaks in the United States, infected over 1800 people and killed seven.[5] In Europe, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported 91,034 cases of Salmonella infection with 65,317 cases related to the 2012 outbreaks.[6] Of those 65,317 cases, there were 61 deaths.[6]

Salmonella bacteria can be found in almost any product or animal that has been exposed to fecal matter.[6] These exposures can occur from crops grown from waste-based fertilizers or from food items handled by infected humans.[7][8] Salmonellosis is an intestinal disease, meaning that the bacteria must be ingested and processed through the intestines in order for infection to occur.[7][8] Thus, salmonellosis is commonly spread to humans through ingestion of contaminated food items.[7][8] It can also be spread through contact with reptiles and birds, usually after the person handles the animal or its environment (without hand-washing immediately) and then touches their mouth or food items.[7] Those infected usually develop symptoms anywhere from 12 to 72 hours after first contact with Salmonella bacteria, and most do not require serious medical attention.[8] This salmonellosis displays itself in humans with fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and, most commonly, diarrhea for a period of up to 7 days.[8] Those requiring hospitalization usually are dehydrated or have extreme diarrhea, which can turn deadly, especially if the salmonella bacteria reaches the bloodstream.[7][8] The elderly, young children, and those with weakened immune systems are most at risk for developing salmonellosis and having severe reactions.[7][8] The most common serotypes of Salmonella in the United States and Europe are Enteritidis and Typhimurium.[6][8]

Origins of outbreak

The 2012 outbreak did not have one start and end date due to the multivariate origination sites and stages of investigation. Each outbreak followed its own pattern of contamination, spread, infection, and containment throughout the course of 2012. Worldwide, there were 15 different foodborne and zoonotic origins of the Salmonella outbreaks.[3][6] Eighteen of the over 2,300 strains of Salmonella were found in infected humans and contaminated products in Europe and the U.S.[6] As with all diseases, there were certain places and serotypes that contributed more to the magnitude of the 2012 outbreak. As such, the origins listed below had the greatest frequency of occurrence and overall impact on society.

Hedgehogs

S. Typhimurium has traditionally been an uncommon serotype of Salmonella; however, beginning in January 2012 through the end of 2012, the number of cases steadily rose, with 18 human cases in the United States alone (spread among eight states).[9] The infection caused one death and four hospitalizations.[9] These infections stem from contact with pet hedgehogs or with the animals' surroundings.[9] No one pet provider was linked to the infected hedgehogs.[9]

Feeder rodents

One epidemic of Salmonella enterica I 4,5,12:i:- in the United States in February 2012 affected 46 people across 22 states.[10] The outbreak seemed to be linked to the handling of live or frozen feeder mice and rats for reptile and amphibian pets.[10] A similar outbreak occurred in the United States and United Kingdom in 2009 and 2010 from the same two breeders implicated in this 2012 occurrence.[10] Also, more than a third of those infected were young children, highlighting their propensity for infection.[10]

Live poultry

The outbreaks in 2012 that occurred due to contact with live poultry were of five different serotypes of Salmonella bacteria originating in three distinct locations. The first infections were reported in February 2012.[11] Spanning 23 states, there were 93 humans infected with the Montevideo serotype of Salmonella.[11] All were infected with this strain from contact with baby ducklings or chicks from the Estes Hatchery located in Springfield, Missouri.[11] This outbreak resulted in one casualty.[11] One month later (March 2012), 46 people in the United States were infected with Salmonella Hadar through contact with live poultry.[12] There were no deaths, and the infected humans were located in 11 different states.[12] The specific hatchery name is withheld, but it was concluded by the CDC that this strain of Salmonella originated in one unnamed hatchery in Idaho.[12] In the same month, one of three strains of Salmonella – Infantis, Newport, or Lille – were contracted by 195 people from contact with live poultry (whether for purposes of agriculture or pet keeping).[13] Of those infected, two died from infection.[13] This particular outbreak, though stemming from only the Mt. Healthy Hatchery in Ohio, expanded across 27 states.[13]

Small turtles

First investigated at the end of March 2012, there were a total of 84 cases of infected humans across 15 states of the United States by November 2012.[14] These people's salmonellosis (either from Salmonella Sandiego or Salmonella Newport) stemmed from contact with small turtles or their habitats.[14] Some of these turtles were purchased from street merchants.[14] No one source of the Salmonella contaminations was identified, and no human deaths occurred.[14] Due to past outbreaks, there is a law in place making it illegal to sell or own a turtle with a shell length less than four inches, as these seem to generally be the sources of most Salmonella bacteria in small turtles.[14]

Raw scraped ground tuna product

First reported in April 2012, an outbreak of salmonellosis caused by rarer serotypes, Salmonella Bareilly and Salmonella Nchanga, was reported in 28 states, mostly in the Eastern U.S., having caused no deaths, but 425 cases of illness and 55 hospitalizations.[15] This outbreak was linked to the consumption of raw scraped ground tuna product.[15] The source was frozen raw yellowfin tuna product aka Nakaochi Scrape manufactured by Moon Marine USA Corporation.[15] This product was voluntarily recalled after the CDC discovered strains of Salmonella in the packages.[15] The company eventually recalled another type of canned tuna for fear it may have been contaminated, too.[15] This outbreak was significant in that it was the first salmonellosis case in the United States connected to raw, scraped tuna products, as well as being the first time S. Nchanga was discovered in food products in the United States.[15]

Smoked salmon

In July 2012, an outbreak of salmonellosis occurred in the Netherlands and the United States.[16] According to the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, by the end of 2012, 1060 people in the Netherlands and 100 in the United States contracted salmonellosis from smoked salmon infected with Salmonella Thompson.[17][18] On November 2, the RIVM confirmed that there were 4 deaths and over 1060 cases linked to S. Thompson in the Netherlands.[17] The infections were linked to smoked salmon from the manufacturer Foppen, where the contamination had occurred.[16] A recall involving a quarter million customers was undertaken in the United States.[19][20] The CDC did not classify this as an outbreak because there were not a verified number of people infected from only this source in the U.S.[3]

Presence in agriculture

Contamination through defecation

Because animals are the main transporters of Salmonella, crops can become infected. This generally occurs because of the use of manure-based fertilizers on farms. Some animals do not appear sick (especially infected poultry); however, they carry the Salmonella in their intestines and when they defecate, the bacteria spreads to the soil.[6] Sometimes, the sick animals manifest the illness in ways similar to humans with similar consequences. They may have diarrhea, fever, and then die if they are not treated.[6] After their death, the other animals raised with them can become infected through contact with their feces.[6] Therefore, if this infected manure is used as a fertilizer for crops, then the crops will contain trace amounts of infectious Salmonella bacteria that can spread to humans after the crops are harvested.[6]

Poultry can become infected by living close together in hatcheries, where multiple animals are defecating. Some poultry are hatched to be sold domestically, while others are hatched for production to be consumed later. If live poultry are infected and sold domestically, they can infect other animals who may be around them in a domestic situation e.g. other pets.[12] Because poultry do not show symptoms, infections are usually not obvious until humans or other animals in contact with the poultry become ill.[6]

Tomatoes

East Coast tomatoes tend to have higher rates of Salmonella infection than West Coast tomatoes.[21] This seems to be due to the microbiome of the East Coast of the United States, where there are far less soil bacteria that destroy Salmonella versus the microbiome of the West Coast where these bacteria are abundant.[21] Because of the anti-salmonella bacteria limiting its spread, fewer people on the West Coast report cases of salmonellosis.[21] Additionally, street-sold natural tomatoes have been consistently tied to outbreaks of Salmonella. Street-sold (unregulated) items are independently produced and sold to consumers. This does not include fresh produce markets. These strong links to salmonellosis is in due in part do the lack of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight on unregistered vendors. Another cause of Salmonella bacteria growth may be due to contact with contaminated irrigation water.[21][22] The tomatoes (or any plant) are much more likely to become infected if the soil in which the roots are located are contaminated or if the actual blossom is contaminated.[21][22] These two entry points lead to the most likely scenarios in which a healthy tomato plant may become infected with some serotype of Salmonella.[22]

End of 2012 outbreak and future prevention

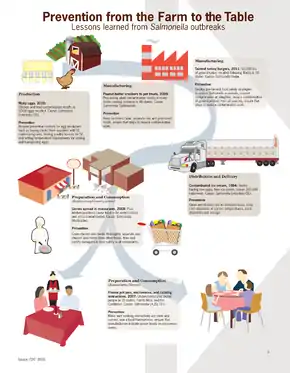

The various outbreaks of Salmonella serotypes in the U.S. and abroad began at different points either in late 2011 or early 2012; however, all cases were concluded at the end of 2012. Those who were infected either persisted through the symptoms or expired from Salmonella's destruction to their immune system.[3] If there was a specific point of origin for an outbreak, a recall of the product helped to decrease more possible exposure. None of the people infected showed symptoms or maintained symptoms into 2013. This biotic disturbance had a major impact on society. It increased awareness about the ease in which bacteria spread among organisms. It helped to prompt researchers to look into ways to prevent crops from becoming contaminated in the field. Most importantly, this disturbance has been occurring with increasing frequency, which seems counter-intuitive because salmonellosis is an easily preventable disease; if simple food safety steps were taken, unnecessary hospitalizations and deaths could have been eliminated in 2012.[23]

In order to prevent serious outbreaks similar to the one in 2012 in the future, some precautions must be taken. When handling food, one must be careful not to cross-contaminate raw poultry products or other meats with other foods.[24] Anyone handling food should also be sure to wash their hands frequently.[24] All persons should wash their hands after using the restroom as bacteria can survive for long periods of time outside of the body and the bacteria will be spread from the unwashed hands to possible food items or anything that may enter the mouth area.[24] When cooking, one should take care to heat foods to at least 167 °F for a minimum of ten minutes to ensure that the entire product is evenly cooked.[25][26][27] This is because heat and ultraviolet radiation are good neutralizers of Salmonella bacterium.[28] Recent outbreaks have occurred, and although not all infections can be eliminated, most can be hindered either through coating crops with Salmonella-fighting bacteria[22] or through human precautions.

References

- "Salmonella Fast Facts". CNN Health. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Public Health". KnowSalmonella. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "List of Selected Multistate Foodborne Outbreak Investigations". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Selected Multistate Outbreak Investigations Linked to Animals and Animal Products". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Reports of Salmonella Outbreak Investigations from 2012". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "The European Union Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-borne Outbreaks in 2012". EFSA Journal. 12 (2): 20–98. 2014. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3547.

- "Diagnosis and Treatment". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "What is Salmonellosis?". Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Marsden-Haug, N; Meyer S; Anderson T; et al. (February 2013). "Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Typhimurium Infections Linked to Contact with Pet Hedgehogs -- United States, 2011-2013". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 62 (4): 73. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Sweat D; Valiani A; Jackson B; et al. (April 20, 2012). "Infections with Salmonella I 4,[5],12:I:- Linked to Exposure to Feeder Rodents -- United States, August 2011-February 2012". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (15): 277. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Montevideo Infections Linked to Live Poultry in Backyard Flocks (Final Update)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Hadar Infections Linked to Live Poultry in Backyard Flocks (Final Update)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Infections Linked to Live Poultry in Backyard Flocks (Final Update)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Eight Multistate Outbreaks of Human Salmonella Infections Linked to Small Turtles (Final Update)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Bareilly and Salmonella Nchanga Infections Associated with a Raw Scraped Ground Tuna Product (Final Update)". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Corder, Mike; Candice Choi (October 2, 2012). "Smoked Salmon Salmonella: Fish Sickens Over 300 In The Netherlands And U.S." Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Salmonella besmetting neemt verder af". Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment.

- "Salmonella in U.S. and Netherlands from Smoked Salmon". HealthAIM. October 2, 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Goetz, Gretchen. "Costco Recalls Smoked Salmon Sold to Quarter of a Million Customers". Food Safety News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Salmonella in Netherlands and US from Dutch smoked fish". BBC News Europe. 2 October 2012.

- Conniff, Richard (September 2013). "Enlisting bacteria and fungi from the soil to support crop plants is a promising alternative to the heavy use of fertilizer and pesticides". Scientific American. 309 (3): 76–79. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0913-76. PMID 24003559.

- Zheng, Jie; et al. (April 2013). "Colonization and Internalization of Salmonella Enterica in Tomato Plants". American Society for Microbiology. 79 (8): 2494–2502. Bibcode:2013ApEnM..79.2494Z. doi:10.1128/aem.03704-12. PMC 3623171. PMID 23377940.

- "healthy pet treats". Wednesday, 11 January 2017

- Beuchat, L. R.; E. K. Heaton (June 1975). "Salmonella Survival on Pecans as Influenced by Processing and Storage Conditions". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 29 (6): 795–801. doi:10.1128/AEM.29.6.795-801.1975. PMC 187082. PMID 1098573.

Little decrease in viable population of the three species was noted on inoculated pecan halves stored at -18, -7, and 5 °C for 32 weeks.

- Partnership for Food Safety Education (PFSE) Fight BAC! Basic Brochure Archived 2013-08-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- USDA Internal Cooking Temperatures Chart Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine. The USDA has other resources available at their Safe Food Handling Archived 2013-06-05 at the Wayback Machine fact-sheet page. See also the National Center for Home Food Preservation.

- Sorrells, K.M.; Speck, M. L.; Warren, J. A. (January 1970). "Pathogenicity of Salmonella gallinarum After Metabolic Injury by Freezing". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 19 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1128/AEM.19.1.39-43.1970. PMC 376605. PMID 5461164.

Mortality differences between wholly uninjured and predominantly injured populations were small and consistent (5% level) with a hypothesis of no difference.

- Goodfellow, S.J.; W.L. Brown (August 1978). "Fate of Salmonella Inoculated into Beef for Cooking". Journal of Food Protection. 41 (8): 598–605. doi:10.4315/0362-028x-41.8.598. PMID 30795117.