Associative visual agnosia

Associative visual agnosia is a form of visual agnosia. It is an impairment in recognition or assigning meaning to a stimulus that is accurately perceived and not associated with a generalized deficit in intelligence, memory, language or attention.[1] The disorder appears to be very uncommon in a "pure" or uncomplicated form and is usually accompanied by other complex neuropsychological problems due to the nature of the etiology.[1] Affected individuals can accurately distinguish the object, as demonstrated by the ability to draw a picture of it or categorize accurately, yet they are unable to identify the object, its features or its functions.

| Associative visual agnosia | |

|---|---|

| |

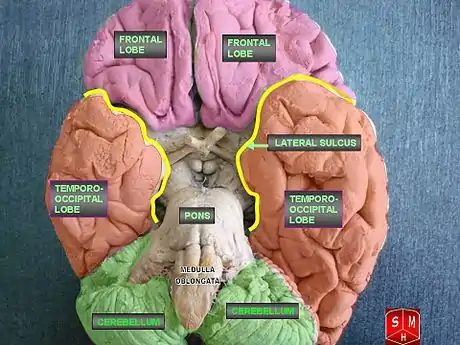

| Inferior view of the brain, depicting the cerebral lobes. Lesions on the occipito-temporal lobes are correlated with associative agnosia. |

Classification

Agnosias are sensory modality specific, usually classified as visual, auditory, or tactile.[2][3] Associative visual agnosia refers to a subtype of visual agnosia, which was labeled by Lissauer (1890), as an inability to connect the visual percept (mental representation of something being perceived through the senses) with its related semantic information stored in memory, such as, its name, use, and description.[4][5][6] This is distinguished from the visual apperceptive form of visual agnosia, apperceptive visual agnosia, which is an inability to produce a complete percept, and is associated with a failure in higher order perceptual processing where feature integration is impaired, though individual features can be distinguished.[7] In reality, patients often fall between both distinctions, with some degree of perceptual disturbances exhibited in most cases, and in some cases, patients may be labeled as integrative agnostics when they fit the criteria for both forms.[1] Associative visual agnosias are often category-specific, where recognition of particular categories of items are differentially impaired, which can affect selective classes of stimuli, larger generalized groups or multiple intersecting categories. For example, deficits in recognizing stimuli can be as specific as familiar human faces or as diffuse as living things or non-living things.[7]

An agnosia that affects hearing, auditory sound agnosia, is broken into subdivisions based on level of processing impaired, and a semantic-associative form is investigated within the auditory agnosias.[2]

Causes

Associative visual agnosias are generally attributed to anterior left temporal lobe infarction (at the left inferior temporal gyrus),[8] caused by ischemic stroke, head injury, cardiac arrest, brain tumour, brain hemorrhage, or demyelination.[7][9] Environmental toxins and pathogens have also been implicated, such as, carbon monoxide poisoning or herpes encephalitis and infrequent developmental occurrences have been documented.[1][10]

Most cases have injury to the occipital and temporal lobes and the critical site of injury appears to be in the left occipito-temporal region, often with involvement of the splenium of the corpus callosum.[11] The etiology of the cognitive impairment, as well the areas of the brain affected by lesions and stage of recovery are the primary determinants of the pattern of deficit.[1] More generalized recognition impairments, such as, animate object deficits, are associated with diffuse hypoxic damage, like carbon monoxide poisoning; more selective deficits are correlated with more isolated damage due to focal stroke.[1]

Damage to the left hemisphere of the brain has been explicitly implicated in the associative form of visual agnosia.[12][13] Goldberg suggested that the associative visual form of agnosia results from damage to the ventral stream of the brain, the occipito-temporal stream, which plays a key role in object recognition as the so-called "what" region of the brain, as opposed to the "where," dorsal stream.[12]

Theoretical explanations

Teuber[14] described the associative agnostic as having a "percept stripped of its meaning," because the affected individual cannot generate unique semantic information to identify the percept, since though it is fully formed, it fails to activate the semantic memory associated with the stimulus.[8] Warrington (1975)[15] offered that the problem lies in impaired access to generic engrams (memory traces) that describe categories of objects made up of a multitude of similar elements.[12] Essentially, damage to a modality-specific meaning process (semantic system), is proposed, either in terms of defective access to or a degradation of semantic memory store for visual semantic representations themselves.[13][16] The fact that agnosias are often restricted to impairments of particular types of stimuli, within distinct sensory modalities, suggests that there are separate modality specific pathways for the meaningful representation of objects and pictures, written material, familiar faces, and colors.[17]

Object recognition model

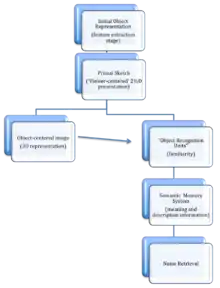

Cognitive psychology often conceptualizes this deficit as an impairment in the object recognition process. Currently visual agnosias are commonly explained in terms of cognitive models of object recognition or identification.[9] The cognitive system for visual object identification is a hierarchal process, broken up into multiple steps of processing.[16]

In the object recognition unit model by Marr (1980),[18] the process begins with sensory perception (vision) of the object, which results in an initial representation via feature extraction of basic forms and shapes. This is followed by an integration stage, where elements of the visual field combine to form a visual percept image, the 'primary sketch'. This is a 2+1⁄2 dimensional (2+1⁄2D) stage with a 'viewer-centered' object representation, where the features and qualities of the object are presented from the viewer's perspective.[5] The next stage is formation of a 3 dimensional (3D) 'object-centered' object representation, where the object's features and qualities are independent of any particular perspective. Impairment at this stage would be consistent with apperceptive agnosia.[1] This fully formed percept then triggers activation of stored structural object knowledge for familiar things.[9] This stage is referred to as "object recognition units" and distinctions between apperceptive and associative forms can be made based on presentation of a defect before or after this stage, respectively.[16] This is the level at which one is proposed to perceive familiarity toward an object, which activates the semantic memory system, containing meaning information for objects, as well as descriptive information about individual items and object classes. The semantic system can then trigger name retrieval for the objects. A patient who is not impaired up until the level of naming, retaining access to meaning information, are distinguished from agnostics and labeled as anomic.[1]

Non-abstracted view

In an alternate model of object recognition by Carbonnel et al.[19] episodic and semantic memory arise from the same memory traces, and no semantic representations are stored permanently in memory. By this view, the meaning of any stimulus emerges momentarily from reactivation of one's previous experiences with that entity. Each episode is made of several components of many different sensory modalities that are typically engaged during interactions with an object. In this scenario, a retrieval cue triggers reactivation of all episodic memory traces, in proportion to the similarity between the cue its 'echo,' the components shared by most activated traces. In a process called 're-injection,' the first echo acts as a further retrieval cue, evoking the 'second echo,' the less frequently associated components of the cue. Thus, the 're-injection' process provides a more complete meaning for the object. According to this model, different types of stimuli will evoke differential 'echos' based on typical interactions with them.[9] For example, a distinction is made between functional and visual components of various stimuli, such that impairment to these aspects of the memory trace will inhibit the re-injection process needed to complete the object representation. This theory has been used to explain category-specific agnosias that impair recognition of various object types, such as animals and words, to different degrees.[9]

Common forms of visual associative agnosia

| Disorder | Recognition impairment | Retained abilities | Location of lesion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual object agnosia | Often specific to a particular category or categories of stimuli, i.e. living/animate things, tools, musical instruments, etc. |

| Bilateral occipito-temporal cortex[11] |

| Associative prosopagnosia | Familiar faces |

| Usually bilateral, sometimes right unilateral, inferior occipital and posterolateral temporal cortex[11] |

| Pure alexia | Written words |

| Left occipital lobe and related fibers connecting right and left hemispheres in subjacent white matter or splenium[11] |

| Cerebral achromatopsia | Color associations |

| Bilateral or left unilateral occipito-temporal cortex[16] |

| Topographical disorientation | Familiar places |

| Right posterior cingulate cortex |

Visual object agnosia

Visual object agnosia (or semantic agnosia) is the most commonly encountered form of agnosia.[16] The clinical "definition" of the disorder is when an affected person is able to copy/draw things that they cannot recognize. Individuals often cannot identify, describe or mimic functions of items, though perception is intact, since images of objects can be copied or drawn.[7] Individuals may retain semantic knowledge of the items, as exemplified during tasks where objects are presented through alternate modalities, through touch or verbal naming or description. Some associative visual object agnostics retain the ability to categorize items by context or general category, though unable to name or describe them.[16] Diffuse hypoxic damage is the most common cause of visual object agnosias.[8]

Category-specific agnosia

Category-specific agnosias are differential impairments in subject knowledge or recognition abilities pertaining to specific classes of stimuli, such as living things vs. non-living things, animate vs. inanimate things, food, metals, musical instruments, etc. Some of the most common category-specific agnosias involve recognition impairments for living things, but not non-living things, or human faces, as in prosopagnosia. This type of deficit is typically associated with head injury or stroke, though other medical conditions have been implicated, such as, herpes encephalitis.[2]

Prosopagnosia

Prosopagnosia (or "face blindness") is a category-specific visual object agnosia, specifically, impairment in visual recognition of familiar faces, such as close friends, family, husbands, wives, and sometimes even their own faces. Individuals are often able to identify others through alternate characteristics, such as, voice, gait, context or unique facial features. This deficit is typically assessed through picture identification tasks of famous persons. This condition is associated with damage to the medial occipito-temporal gyri, including the fusiform and lingual gryi, as the suggested location of the brain's face recognition units.[7][11][16]

Associative and apperceptive forms

Two subtypes are distinguished behaviorally as being associative or apperceptive in nature. Associative prosopagnosia is characterized by an impairment in recognition of a familiar face as familiar; however, individuals retain the ability to distinguish between faces based on general features, such as, age, gender and emotional expression.[20] This subtype is distinguished through facial matching tasks or feature identification tasks of unknown faces.[16]

Pure alexia

Pure alexia ("alexia without dysgraphia" or "pure word blindness") is a category-specific agnosia, characterized by a distinct impairment in reading words, despite intact comprehension for verbally presented words, demonstrating retained semantic knowledge of words.[7][20] Perceptual abilities are also intact, as assessed by word-copying tasks.[2]

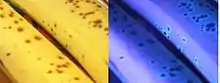

Cerebral achromatopsia

Cerebral achromatopsia, also known as Color agnosia, is a category-specific semantic impairment pertaining to semantic color associations, such that individuals retain perceptual abilities for distinguishing color, demonstrated through color categorization or hue perception tasks; however knowledge of typical color-object relationships is defective.[7][8][16] Color agnostics are assessed on performance coloring in black and white images of common items or identifying abnormally colored objects within a set of images.[2] For example, a color agnostic may not identify a blue banana as being improperly colored.

Overlap with color anomia

This deficit should be distinguished from color anomia, where semantic information about color is retained, but the name of a color cannot be retrieved, though co-occurrence is common. Both disorders linked to damage in the occipito-temporal cortex, especially in the left hemisphere, which is believed to play a significant role in color memory.[16]

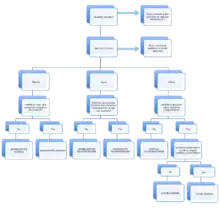

Diagnosis

A recognition disorder is not considered to be agnosia unless there is a lack of aphasia, dementia, or other generalized defect that affects any stage of the object recognition process, such as, deficiencies in intelligence, linguistic ability, memory, attention or sensory perception.[1][2] Therefore, individuals must be assessed for language ability, auditory comprehension, fluency, repetition, praxis, and reading and writing.

Goals of clinical assessment of agnosia

- Ruling out alternative conditions leading to the recognition impairment, such as, primary sensory disruption, dementia, aphasia, anomia, or unfamiliarity with the object category or elements.

- Determination of the scope and specific nature of the recognition impairment. Including:

- Specific sensory modality

- Specific category of stimuli

- Specific conditions under which recognition is possible[1]

Testing

Specialists, like ophthalmologists or audiologists, can test for perceptual abilities. Detailed testing is conducted, using specially formulated assessment materials, and referrals to neurological specialists is recommended to support a diagnosis via brain imaging or recording techniques. The separate stages of information processing in the object recognition model are often used to localize the processing level of the deficit.[1]

Testing usually consists of object identification and perception tasks including:

- object-naming tasks

- object categorization or figure matching

- drawing or copying real objects or images or illustrations

- unusual views tests

- overlapping line drawings

- partially degraded or fragmented image identification

- face or feature analysis

- fine line judgment

- figure contour tracking

- visual object description

- object-function miming

- tactile ability tests (naming by touch)

- auditory presentation identification[5][8]

Overlap with optic aphasia

Sensory modality testing allows practitioners to assess for generalized versus specific deficits, distinguishing visual agnosias from optic aphasia, which is a more generalized deficit in semantic knowledge for objects that spans multiple sensory modalities, indicating an impairment in the semantic representations themselves.[13]

Apperceptive vs. associative

The distinction between visual agnosias can be assessed based on the individual's ability to copy simple line drawings, figure contour tracking, and figure matching.[5] Apperceptive visual agnostics fail at these tasks, while associative visual agnostics are able to perform normally, though their copying of images or words is often slavish, lacking originality or personal interpretation.[1]

Treatment

The affected individual may not realize that they have a visual problem and may complain of becoming "clumsy" or "muddled" when performing familiar tasks such as setting the table or simple DIY. Anosognosia, a lack of awareness of the deficit, is common and can cause therapeutic resistance.[2] In some agnosias, such as prosopagnosia, awareness of the deficit is often present; however shame and embarrassment regarding the symptoms can be a barrier in admission of a deficiency.[16] Because agnosias result from brain lesions, no direct treatment for them currently exists, and intervention is aimed at utilization of coping strategies by patients and those around them. Sensory compensation can also develop after one modality is impaired in agnostics[1]

General principles of treatment:

- restitution

- repetitive training of impaired ability

- development of compensatory strategies utilizing retained cognitive functions[1]

Partial remediation is more likely in cases with traumatic/vascular lesions, where more focal damage occurs, than in cases where the deficit arises out of anoxic brain damage, which typically results in more diffuse damage and multiple cognitive impairments.[2] However, even with forms of compensation, some affected individuals may no longer be able to fulfill the requirements of their occupation or perform common tasks, such as, eating or navigating. Agnostics are likely to become more dependent on others and to experience significant changes to their lifestyle, which can lead to depression or adjustment disorders.[1]

References

- Bauer, Russell M. (2006). "The Agnosias". In Snyder, P.J. (ed.). Clinical Neuropsychology: A Pocket Handbook for Assessment (2nd Ed). P.D. Nussbaum, & D.L. Robins. American Psychological Association. pp. 508–533. ISBN 978-1-59147-283-4. OCLC 634761913.

- Ghadiali, Eric (November–December 2004). "Agnosia" (PDF). ANCR. 4 (5). Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Reed CL, Caselli RJ, Farah MJ (June 1996). "Tactile agnosia. Underlying impairment and implications for normal tactile object recognition". Brain. 119 (3): 875–88. doi:10.1093/brain/119.3.875. PMID 8673499.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th Ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2009.

- Carlesimo, Giovanni A.; Paola Casadio; Maurizio Sabbadini; Carlo Caltagirone (September 1998). "Associative visual agnosia resulting from a disconnection between intact visual memory and semantic systems". Cortex. 34 (4): 563–576. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70514-8. PMID 9800090. S2CID 4483007. Archived from the original on 2013-02-21. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- Lissauer, H (1890). "Ein Fall von Seelenblinheit nebst einem Beitrag zur Theorie derselben". Arch Psychiatry. 21 (2): 222–270. doi:10.1007/bf02226765. S2CID 29786214.

- Biran, I.; Coslett, H. B. (2003). "Visual agnosia". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 3 (6): 508–512. doi:10.1007/s11910-003-0055-4. ISSN 1528-4042. PMID 14565906. S2CID 6005728.

- Greene, J. D. W (2005). "Apraxia, agnosias, and higher visual function abnormalities". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 76: 25–34. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.081885. PMC 1765708. PMID 16291919.

- Charnallet, A.; S. Carbonnelb; D. Davida; O. Moreauda (March 2008). "Associative visual agnosia: A case study". Behavioural Neurology. 19 (1–2): 41–44. doi:10.1155/2008/241753. PMC 5452468. PMID 18413915.

- Warrington, Elizabeth K.; T. Shallice (1984). "Category Specific Semantic Impairments" (PDF). Brain. 107 (3): 829–854. doi:10.1093/brain/107.3.829. PMID 6206910. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Kiernan, J.A. (2005). Barr's The Human Nervous System (8th Ed.). Baltimore & Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. pp. Table 15–1.

- Goldberg, Elkhonon (January 1990). "Associative Agnosias and the Function of the Left Hemisphere" (PDF). Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 12 (4): 467–484. doi:10.1080/01688639008400994. PMID 2211971. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- McCarthy, Rosaleen A.; Elizabeth K. Warrington (November 1987). "Visual associative agnosia: a clinico-anatomical study of a single case". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 49 (11): 1233–1240. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1233. PMC 1029070. PMID 3794729.

- Weiskrantz, L, ed. (1968). "Alteration of perception and memory in man". Analysis of Behavioral Change. New York: Harper and Row.

- Warrington, E. K. (1975). "The selective impairment of semantic memory". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 27 (4): 635–657. doi:10.1080/14640747508400525. PMID 1197619. S2CID 2178636.

- De Renzi, Ennio (2000). "Disorders of Visual Recognition" (PDF). Seminars in Neurology. 20 (4): 479–85. doi:10.1055/s-2000-13181. PMID 11149704. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-01.

- Mack, James L.; Francois Boller (1977). "Associative visual agnosia and its related deficits: The role of the minor hemisphere in assigning meaning to visual perceptions". Neuropsychologia. 15 (2): 345–349. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(77)90044-6. PMID 846640. S2CID 23996895.

- Marr D (July 1980). "Visual information processing: the structure and creation of visual representations". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 290 (1038): 199–218. Bibcode:1980RSPTB.290..199M. doi:10.1098/rstb.1980.0091. PMID 6106238.

- Carbonnel, S.; A. Charnallet; D. David; J. Pellat (1997). "One or several semantic system(s): maybe none. Evidence from a case study of modality and category-specific "semantic" im- pairment". Cortex. 33 (3): 391–417. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70227-2. PMID 9339326. S2CID 4479759.

- Farah, Martha J., ed. (2000). "Chapter 12: Disorders". Patient-Based Approaches to Cognitive Neuroscience. Todd E Feinberg. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. pp. 79–84, 143–154. ISBN 978-0262561235. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-04-10.