Balmis Expedition

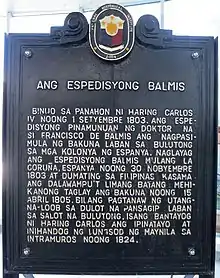

The Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition (Spanish: Real Expedición Filantrópica de la Vacuna), commonly referred to as the Balmis Expedition, was a Spanish healthcare mission that lasted from 1803 to 1806, led by Dr Francisco Javier de Balmis, which vaccinated millions of inhabitants of Spanish America and Asia against smallpox. The vaccine was actually transported through children: orphaned boys who sailed with the expedition.

Background

Smallpox, a devastating disease, decimated the populations of the Americas after it had been brought over from Europe by the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s,[1] but also threatened the slave trade with small pox epidemics on board of the ships carrying human cargo.[2]

Vaccination, that is inoculation with cowpox material, is a much safer way to prevent smallpox than older methods such as variolation, inoculation with smallpox material, which ran the risk of itself spreading smallpox. Vaccination had been pioneered in the West by the English physician Edward Jenner in 1798. At that time, about 400,000 Europeans died each year from the disease.[1] At the same time, Europe engaged in slave trade and the Haitian Revolution (1794-1804) occurred. Francisco Javier de Balmis was a military physician.[3]

Expedition

In November 1794 the daughter of King Charles IV of Spain, Infanta Maria Teresa, had died from smallpox. He had heard of the vaccine discovery. Colombia and Ecuador experienced a smallpox epidemic and called on the king for supplies.[3]

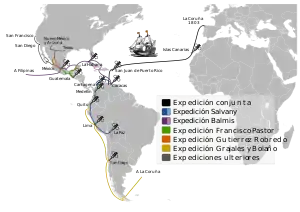

On 30 November 1803, the expedition set off from A Coruña in northwest Spain sailing on Maria Pita. It carried 22 orphan boys (aged 3 to 10) to act as carriers of the cowpox virus. The boys were necessary because the vaccine consisted of infecting patients with cowpox, which is a virus closely related to smallpox but produces a much milder disease that confers immunity to both. However, only an active infection could be transferred to successive patients, so two boys were infected with cowpox at the beginning of the voyage, with two more infected at a time as it progressed across the Atlantic and beyond.[4] The medical staff and caretakers for the boys consisted of Balmis, a deputy surgeon, two assistants, two first-aid practitioners, three nurses, and Isabel Zendal Gómez, the rectoress of Casa de Expósitos, an A Coruña orphanage.[5]

The mission took the vaccine to the Canary Islands, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, the Philippines and China.[6] The ship carried also scientific instruments and translations of the Historical and Practical Treatise on the Vaccine by Moreau de Sarthe to be distributed to the local vaccine commissions to be founded.[7]

In Puerto Rico, the local population had already been inoculated from the Danish colony of Saint Thomas. In Venezuela, the expedition divided at La Guaira. Balmis went to Caracas and later to Havana.

At Balmis’ request Cuba sent three enslaved girls to Campeche, Mexico, as additional carriers of the vaccine; following Mexican independence and emancipation, Mexico continued to bring in slaves from Cuba as vaccine carriers.[3]

The Venezuelan poet Andrés Bello wrote an ode to Balmis. José Salvany, the deputy surgeon, went toward today's Colombia and the Viceroyalty of Peru (Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Bolivia). They took seven years and the toils of the voyage brought death to Salvany (Cochabamba, 1810).In New Spain, Balmis took 25 orphans to maintain the infection during the crossing of the Pacific. In the Philippines, they received help from the Catholic church, which was initially reluctant until Governor-General Rafael Aguilar made an example by vaccinating his five children. Balmis sent most of the expedition back to New Spain while he went on to China, where he visited Macau and Canton.[8] On his way back to Spain in 1806, Balmis offered the vaccine to the British authorities in Saint Helena, despite the Anglo-Spanish War (1796–1808).[7]

Legacy

Balmis expedition may be considered the first international healthcare expedition in history.[7][9] Jenner himself wrote, "I don't imagine the annals of history furnish an example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as this."[1]

In 2006, Julia Alvarez wrote a fictional account of the expedition from the perspective of its only female member in Saving the World (2006).

References

- Tarrago, Rafael E. (2001). "The Balmis-Salvany Smallpox Expedition: The First Public Health Vaccination Campaign in South America". Perspectives in Health. Vol. 6, no. 1. Pan-American Health Organization.

- Farren E. Yero (7 December 2020). "An Eradication: Empire, Enslaved Children, and the Whitewashing of Vaccine History". Age of Revolutions. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Tenorio, Rich (16 February 2021). "An 1800s vaccine campaign in Mexico offers lessons in beating Covid". Mexico News daily. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- Tucker JB (2001). Scourge: The Once and Future Threat of Smallpox. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-87113-830-9.

- McIntyre JWR, Stuart HC (1999). "Medicine in Canada: Smallpox and its control in Canada". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 161 (12): 1543–1547. PMC 1230874. PMID 10624414.

- de Romo, Ana Cecilia Rodríguez (1997). Inoculation in the 1799 smallpox epidemic in Mexico: Myth or real solution?. Antilia:Spanish Journal of History of Natural Sciences and Technology.

- Franco-Paredes, Carlos; Lammoglia, Lorena; Santos-Preciado, José Ignacio (2005). "The Spanish Royal Philanthropic Expedition to Bring Smallpox Vaccination to the New World and Asia in the 19th Century". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (9): 1285–1289. doi:10.1086/496930. JSTOR 4463512. PMID 16206103.

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (6 December 2017). "Vaccine expedition in early 1800s". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- La Coruña: A progressive city Archived 2004-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, historical information as part the official web site for the city of La Coruña. Verified availability 2005-03-03.

Further reading

- Mark, Catherine; Rigau-Perez, Jose G. (2009). "The World's First Immunization Campaign: The Spanish Smallpox Vaccine Expedition, 1803–1813". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 83 (1): 63–94. ISSN 0007-5140.

External links

- En el nombre de los Niños. Real expedición Filantrópica de la Vacuna 1803-1806. Spanish language PDF book by the Spanish Pediatry Association.