Bruck syndrome

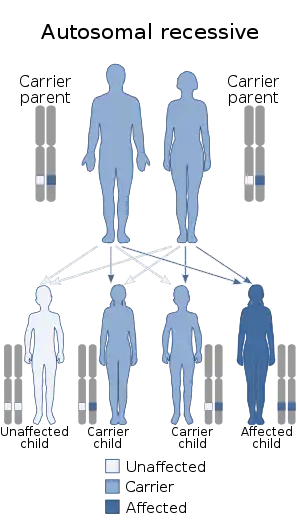

Bruck syndrome is characterized as the combination of arthrogryposis multiplex congenita and osteogenesis imperfecta. Both diseases are uncommon, but concurrence is extremely rare which makes Bruck syndrome very difficult to research.[1] Bruck syndrome is thought to be an atypical variant of osteogenesis imperfecta most resembling type III, if not its own disease.[2][3] Multiple gene mutations associated with osteogenesis imperfecta are not seen in Bruck syndrome. Many affected individuals are within the same family, and pedigree data supports that the disease is acquired through autosomal recessive inheritance.[4] Bruck syndrome has features of congenital contractures, bone fragility, recurring bone fractures, flexion joint and limb deformities, pterygia, short body height, and progressive kyphoscoliosis. Individuals encounter restricted mobility and pulmonary function. A reduction in bone mineral content and larger hydroxyapatite crystals are also detectable[5] Joint contractures are primarily bilateral and symmetrical, and most prone to ankles.[3] Bruck syndrome has no effect on intelligence, vision, or hearing.[4]

| Bruck syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Osteogenesis imperfecta-congenital joint contractures syndrome |

| |

| Bruck syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

Genetics

The genetics of Bruck syndrome differs from osteogenesis imperfecta. Osteogenesis imperfecta involves autosomal dominant mutations to Col 1A2 or Col 1A2 which encode type 1 procollagen.[6] Bruck syndrome is linked to mutations in two genes, and therefore is divided in two types. Bruck syndrome type 1 is caused by a homozygous mutation in the FKBP10 gene. Type 2 is caused by a homozygous mutation in the PLOD2 gene.[6]

Mechanism

Type 1 encodes FKBP65, an endoplasmic reticulum associated peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase (PPIase) that functions as a chaperone in collagen biosynthesis. Osteoblasts deficient in FKBP65 have a buildup of procollagen aggregates in the endoplasmic reticulum which reduces their ability to form bone.[7] Furthermore, Bruck syndrome type 1 patients have under-hydroxylated lysine residues in the collagen telopeptide and as a result show diminished hydroxylysylpyridinoline cross-links.[6]

Type 2 encodes the enzyme, lysyl hydroxylase 2, which catalyzes hydroxylation of lysine residues in collagen cross-links. PLOD2 is most expressed in active osteoblasts since collagen cross-linking is tissue-specific. Mutation in PLOD2 alters the structure of telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase and prevents fibril formation of collagen type 1. Bone analysis shows the lysine residues of telopeptides in collagen type 1 are under-hydroxylated.[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Bruck syndrome must distinguish the association of contractures and skeletal fragility. Ultrasound is used for prenatal diagnosis. The diagnosis of a neonate bears resemblance to arthrogryposis multiplex congenital, and later in childhood to osteogenesis imperfecta.[1]

Management

Until more molecular and clinical studies are performed there will be no way to prevent the disease. Treatments are directed towards alleviating the symptoms. To treat the disease it is crucial to diagnose it properly.[6] Orthopedic therapy and fracture management are necessary to reduce the severity of symptoms. Bisphosphonate drugs are also an effective treatment.[4]

History

The first case was in 1897 of a male who was described by Bruck as having bone fragility and bone contractures.[4] Bruck was credited with the first description and the disease's eponym.[1]

References

- Mokete, L.; Robertson, A.; Viljoen, D.; Beighton, Peter (2005). "Bruck syndrome: congenital joint contractures with bone fragility". Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 10 (6): 641–646. doi:10.1007/s00776-005-0958-9. PMID 16307191. S2CID 46110203.

- Berg, C.; Geipel, A.; Noack, F; et al. (2005). "Mutations in FKBP10 cause recessive osteogenesis imperfecta and bruck syndrome". Prenatal Diagnosis. 25 (3): 545–548. doi:10.1002/jbmr.250. PMC 3179293. PMID 20839288.

- Blacksin, M.; Pletcher, B.; David, Miriam; et al. (1998). "Osteogenesis imperfecta with joint contractures: Bruck syndrome". Pediatric Radiology. 28 (2): 117–119. doi:10.1007/s002470050309. PMID 9472060. S2CID 12863084.

- Datta, V.; Sinha, A.; Saili, A.; et al. (2005). "Osteogenesis Imperfecta". Journal of Pediatrics. 72 (5): 441–442. doi:10.1007/BF02731745. PMID 15973030. S2CID 24986309.

- Banks, R.; Robins, S.; Wijmenga; et al. (1999). "Defective collagen crosslinking in bone, but not in ligament or cartilage, in Bruck syndrome: Indications for a bone-specific telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase on chromosome 17". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (3): 1054–1058. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.1054B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.3.1054. PMC 15349. PMID 9927692.

- Yapicioglu, H.; Ozcan, K.; Arikan, O.; et al. (2009). "Bruck syndrome: osteogenesis imperfecta and arthrogryposis multiplex congenital". Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 29 (2): 159–1662. doi:10.1179/146532809x440798. PMID 19460271. S2CID 206847487.

- Shaheen, Ranad; Al-Owain, Mohammed; Faqeih, Eissa; Al-Hashmi, Nadia; Awaji, Ali; Al-Zayed, Zayed; Alkuraya, Fowzan S (2011). "Mutations in FKBP10 cause both Bruck syndrome and isolated osteogenesis imperfecta in humans". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 155 (6): 1448–1452. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34025. PMID 21567934. S2CID 40133519.

Further reading

- Breslau-Siderius, E. J.; et al. (1998). "Brack syndrome: a rare combination of bone fragility and multiple congenital joint contractures". Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 7 (1): 35–38. doi:10.1097/01202412-199801000-00006.